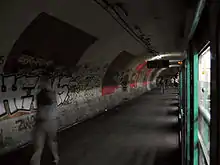

Ghost stations of the Paris Métro are stations that have been closed to the public and are no longer used in commercial service. For historical or economical reasons, many stations on the Paris Métro have been made inaccessible and lie unused, conferring a sense of mystery over Parisians.

The majority of these ghost stations were closed when France entered World War II in September 1939, and some have been closed ever since. Others have been reused or disappeared completely as the network evolved. Two stations were constructed but never actually used, and today still lie inaccessible to the public. Three others were designed but were never serviced by a Métro line.

Unopened stations

Two stations on the Paris Métro were constructed but never used, and have no way to be accessed by the public: Porte Molitor and Haxo.[1][2] Only during rare special service to these stations can they be visited.

Porte Molitor is a station constructed in 1923 on a linking of lines 9 and 10 and was originally intended to service the stadiums Parc des Princes and Roland Garros on the nights of matches.[1][2] Logistics of this service became too complex, however, and the project was abandoned; access to the station was never constructed. The tracks today serve as a garage for trains.[3]

A special tunnel, the voie des Fêtes, links the Place des Fêtes to the Porte des Lilas with an intermediary station called Haxo, constructed in 1921.[4] This tunnel was intended to connect lines 3 and 7 (now 3bis and 7bis). Actually the tunnel was never used as it was decided to run a shuttle service between the stations of each of these lines. This shuttle proved unpopular with passengers and service stopped in 1939. Haxo has never been used for passenger transport, and there is no street-level access.[5]

Stations closed and later reopened

At the beginning of World War II, the French government put into action a plan that called for reduced service on the Métro network; specifically, it closed all but 85 stations. The majority of stations that were closed reopened in the following years, however some lightly trafficked and therefore unprofitable stations remained closed for a longer time.

Varenne (line 14, now line 13) reopened on 24 December 1962, followed by the station Bel-Air (line 6) on 7 January 1963.[6] Rennes (line 12) and Liège (line 13) reopened to the public after about 30 years of being closed, on 20 May 1968 and 16 September 1968 respectively.[6][7] These stations were subject to abbreviated schedules: they closed at 8 PM on weekdays and Saturdays, and did not open on Sundays and holidays.[7] Rennes returned to normal service schedules on 6 September 2004 and Liège, the last station on an abbreviated schedule of the network, returned to normal hours on 4 December 2006.[8]

Cluny (line 10) remained forgotten for almost half a century, however the construction of the train station Saint-Michel - Notre-Dame to service line B of the RER caused it to be reopened in order to provide a connection to line 10. It was reopened to the public on 17 February 1988, the day on which the RER line B station was opened. The station was renamed Cluny – La Sorbonne.[4]

Closed stations

The station Saint-Martin was closed in 1939, opened after the Liberation and closed again. This station was situated on the Grands Boulevards and therefore served as an important access point, however it was eventually closed again because of its proximity—less than 100 metres (110 yd)—to the neighbouring station Strasbourg – Saint-Denis.[2]

Three stations have remained closed since 1939: Arsenal (line 5), Champ de Mars (line 8), and Croix-Rouge (line 10).[4]

Two other open stations contain unused platforms (that is they are inaccessible to the public): Porte des Lilas – Cinéma (line 3bis) and Invalides (a platform for line 8 is unused after renovations made to the station).[4]

Merged stations

As a result of the expansion of line 3 to Gallieni, the station Martin Nadaud was integrated into the station Gambetta. The station still exists today: it is situated in the extension of the Gambetta station in the direction of Pont de Levallois, at a site surrounded by a gate, with its platforms being repurposed, and now they’re used as walkways.[4]

Repurposed stations

Gare du Nord USFRT, the old terminus of line 5 until 1942 and situated on the boulevard de Danain, became a ghost station after the expansion of line 5 to Pantin, which involved the construction of a new station under the rue du Faubourg-Saint-Denis. It has since served as the center for training RATP drivers.[4]

The station Olympiades was used as a service depot for line 14 before the expansion of the tunnel to Maison Blanche and the creation of a new service depot.[9]

The old terminus of line 3 at Villiers was also turned into a training center for the RATP, just outside Parc Monceau.[4]

Moved stations

Four stations have been moved during the construction and extension of lines:[4]

- Porte de Versailles: old terminus of line A (Now Line 12) of the former Nord-Sud Company, at the end of the current station.

- Victor Hugo: the station was moved a few hundred meters to the east due to new rolling stock which consisted of elongated cars, proving too long for the original station's platforms, which were short and tightly curved.

- Loop of Porte Maillot: old terminus of line 1 before its extension to Pont de Neuilly. At one point, one of its platforms served as a stateroom for the RATP. Since the beginning of 2007, the loop has been undergoing renovations to become an extra service depot for the future MP 05 rolling stock, part of the automation of line 1.

- Les Halles: the station was reconstructed in 1977 a few dozen metres towards the east (parallel to the old station) in order to allow for a better connection with the newly constructed RER station. It does not use any part of the old station.

Abandoned plans for stations

Three other stations had been planned, outside the neighbourhood of La Défense and the Orly Airport, but have never been served by any lines. Two are situated under the business district, and another under the southern part of the Orly Airport. These stations consist only of a concrete box, void of any further development.[4]

Since the expansion of line 1 to Pont de Neuilly in 1937, the future expansion to La Défense had already been considered. Outside of the flagstone pedestrian walks, which include a number of platforms and underground parking from the 1960s and 1970s, the Établissement public pour l'aménagement de la région de la Défense (EPAD) reserved two areas destined to hold two future Métro stations on the axis intended to be served by the line. La Défense – Michelet and Élysées – La Défense are situated under the neighbourhood of Michelet and the apartment building Élysée Défense, respectively.[4]

However, as a result of the planning for the expansion, which was not completed until the 1990s, the complexity and the cost of an under-river crossing in this area was judged to be too prohibitive to complete. Instead, the crossing of the Seine was achieved by passing over the pont de Neuilly, and not in a tunnel as had previously been planned. Thus, the two areas reserved for these stations are not serviced and remain accessible only via a trap door five floors below ground level in an underground parking lot. The current line was realized in part by the number of lanes on the A14 autoroute, which were reduced to 2×2 instead of 3×3, as had previously been planned.[10]

Orly-Sud was conceived at the same time as the terminal, and was dug out under the building in preparation of a future expansion of the Métro to this location. However no such expansion ever occurred, and the automated Métro Orlyval instead opened in 1997 without using the location that had been reserved for the Métro station. The station has now sat as a simple box for more than half a century.[4]

See also

Notes

- 1 2 Patat, Jean-Christophe. "Le metro secret de Paris: la station Molitor" [Paris' secret metro: Molitor Station] (in French). Retrieved March 28, 2010.

- 1 2 3 "Le métro inattendu / Stations fantômes" [The Unexpected Métro / Ghost Stations]. le métro parisien (in French). Archived from the original on February 15, 2010. Retrieved March 29, 2010.

- ↑ Lamming, 2001

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 "Les stations oubliées" [The Forgotten Stations]. SYMBIOZ (in French). Retrieved April 4, 2010.

- ↑ Patat, Jean-Christophe. "Le Metro Secret de Paris : Haxo" [Paris' Secret Metro: Haxo] (in French). Retrieved March 29, 2010.

- 1 2 "Paris Metro Maps: timeline". Archived from the original on November 14, 2010. Retrieved April 4, 2010.

- 1 2 "Une histoire belge - 1er septembre 2004" [A Belgian Story - September 1, 2004] (in French). September 1, 2004. Archived from the original on April 17, 2010. Retrieved April 4, 2010.

- ↑ "La Station "Liège"" ['Liège' Station]. SYMBIOZ (in French). Retrieved April 4, 2010.

- ↑ "Olympiades". SYMBIOZ (in French). Retrieved April 4, 2010.

- ↑ "Les coulisses de la Défense – Une Station de métro sans métro" [The Backstage of La Défense – A Métro Station without a Métro]. Defense-92.fr (in French). Archived from the original on March 27, 2010. Retrieved March 29, 2010.

References

- Guerrand, Roger-Henri (1999). L'aventure du métropolitain [The Métropolitain Adventure] (in French). Paris: La découverte. ISBN 2-7071-1642-4.

- Hallsted-Baumert, Sheila; Gasnault, François; Zuber, Henri (1997). Métro-Cité : le chemin de fer métropolitain à la conquête de Paris, 1871–1945 (in French). Régie autonome des transports parisiens, Archives de Paris. Paris: musées de la ville de Paris. ISBN 2-87900-374-1.

- Lamming, Clive (2001). Métro insolite [Unusual Métro] (in French). Paris: Parigramme. ISBN 2-84096-190-3.

- Robert, Jean (1983). Robert, Jean (ed.). Notre Métro [Our Métro] (in French) (2nd ed.). Paris.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Tricoire, Jean (1999). La Vie du Rail (ed.). Un siècle de métro en 14 lignes. De Bienvenüe à Météor [A Century of Métro in 14 Lines. From Bienvenüe to Météor] (in French). Paris: La vie du rail. ISBN 2-902808-87-9.

- Zuber, Henri (1996). Le patrimoine de la RATP [The Heritage of the RATP] (in French). Charenton-le-Pont: Flohic éditions. ISBN 2-84234-007-8.

External links

- Phantom Train Stations — articles with description and photographs of ghost stations of Paris metro

- Tourists throng Paris's 'ghost' metro stations - Travel article describing a tour of the Ghost Stations of the Paris Metro

- Metro magic - Travel article by Andrew Martin of a tour of several abandoned Metro stations