| Gingival sulcus | |

|---|---|

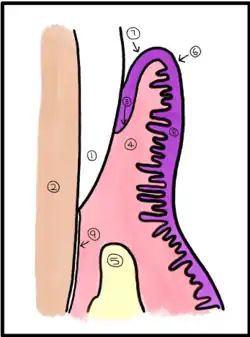

Gingival sulcus (G). Other letters: A, crown of the tooth, covered by enamel. B, root of the tooth, covered by cementum. C, alveolar bone. D, subepithelial connective tissue. E, oral epithelium. F, free gingival margin. H, principal gingival fibers. I, alveolar crest fibers of the PDL. J, horizontal fibers of the PDL. K, oblique fibers of the PDL. | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | sulcus gingivalis |

| TA98 | A05.1.01.111 |

| TA2 | 2793 |

| FMA | 74580 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The gingival sulcus is an area of potential space between a tooth and the surrounding gingival tissue and is lined by sulcular epithelium. The depth of the sulcus (Latin for groove) is bounded by two entities: apically by the gingival fibers of the connective tissue attachment and coronally by the free gingival margin. A healthy sulcular depth is three millimeters or less, which is readily self-cleansable with a properly used toothbrush or the supplemental use of other oral hygiene aids.

Anatomy

2) Dentin

3) Junctional epithelium

4) Connective tissue

5) Alveolar bone

6) Gingival margin

7) Sulcular epithelium

8) Gingival epithelium

9) Cementum

The dentogingival tissues consist of many constituents, such as the enamel or cementum of the tooth and the connective tissue supporting epithelia like the junctional epithelium, the gingival epithelium and the sulcular epithelium. The junctional epithelium is developed during the eruption of teeth when the reduced enamel epithelium merges with the oral epithelium The reduced enamel epithelium forms the first junctional epithelium and is firmly attached to the enamel. In certain cases where gingival recession has occurred, the junctional epithelium will attach to the cementum instead.[1][2]

The non-keratinised stratified squamous sulcular epithelium is thicker than the junctional epithelium and is attached coronally to the junctional epithelium but is not attached to the surface of teeth. Gingival sulcus, also known as gingival crevice, refers to the space between the tooth surface and the sulcular epithelium. At the free gingival margin, the sulcular epithelium is continuous with the gingival epithelium. Both the attached gingivae and the free gingivae are included as part of the gingival epithelium.

While the junctional epithelium is a stratified and thin epithelium that is attached to the tooth surface, the epithelium of the gingival sulcus is stratified squamous and thicker non-keratinised. Presence of Rete Pegs which may be prominent epithelial ridges can also be found in the gingival epithelium that is a stratified squamous, thick and para-keratinised epithelium.

Basic periodontal examination (BPE)

The Basic Periodontal Examination (BPE) is a quick and straightforward method to systematically screen the gingival and periodontal health of patient and determine the next stages of management in terms of further assessment or treatment that a patient might require.[3]

Recording of examination

1) The patient's dentition is divided into six sextants – three sextants for the mandible and maxillary respectively. All teeth, except the 3rd molars, are examined (note the 3rd molars are included if there are no other molars in that sextant). The sextants include:

a. Upper Right (17 to 14)

b. Upper Anterior (13 to 23)

c. Upper Left (24 to 27)

d. Lower Right (47 to 44)

e. Lower Anterior (43 to 33)

f. Lower Left (34 to 37)

For a sextant to be recorded, at least two teeth must be present. Otherwise, the lone standing tooth will be included with the recordings of the adjacent sextant.

_Probe.png.webp)

2) A World Health Organization (WHO) Probe should be used. Refer to attached picture for WHO Probe. The World Health Organization (WHO) Probe has a ball ended tip which is 0.5mm in diameter and some have 2 black bands for dental professionals to measure periodontal pocket depth. A light force equivalent to the weight of the probe should be used. World Health Organization (WHO) Probe ranges in mass from 20-25 grams.

3) The probe should be run around the gingival pockets and the highest score derived in each sextant derived should be recorded.

4) Scoring codes range from 0 to 4. This can be accessed based on the flow table attached. A “*” is recorded when a furcation is involved.

5) For patients with BPE scores of codes 3 and 4, more detailed charting is required. The presence of code 3 would indicate that a 6-point pocket charting in the sextant(s) where code 3 was recorded is required. If code 4 is recorded, a 6-point pocket charting throughout the entire dentition would be required.

Usually, radiographs would be taken to evaluate alveolar bone levels for teeth or sextants where BPE codes 3 or 4 are found assuming no false pockets.

Timing of examination

Basic Periodontal Examination (BPE) should be recorded for:

● All new patients ● Patients with code 0, 1 and 2 at least once annually

Guidance on interpretation of BPE scores

A myriad of factors, which are patient specific, can affect the BPE scores derived. Hence, dental professionals should use their expertise, knowledge and experience to form a reasonable decision when interpreting BPE scores. The BPE scores should be taken into account alongside other factors when being interpreted. A general guideline is:

- Score 0: There is no need for periodontal treatment.

- Score 1: Provide patient with Oral hygiene instruction (OHI).

- Score 2: Provide patient with Oral hygiene instruction (OHI) and remove plaque retentive factors, including all supra- and subgingival calculus and any restoration overhangs.

- Score 3: Provide patient with Oral hygiene instruction (OHI) and root surface debridement (RSD).

- Score 4: Provide patient with Oral hygiene instruction (OHI) and root surface debridement (RSD). In addition, patient should be evaluated for the requirement of more complex treatment. A referral to specialists may be needed.

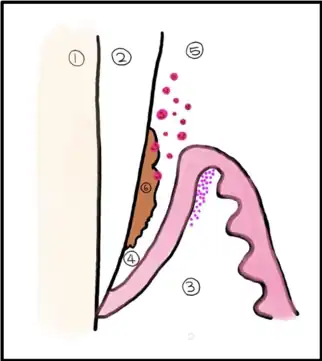

Physiological immune surveillance

After supra-gingival oral hygiene cleaning, plaque biofilm will quickly develop at the gingival margin and will enter the gingival sulcus after some time. The junctional epithelium, which is at the base of the gingival sulcus, permits plaque bacteria and its toxin to enter the underlying gingival connective tissue via the large spaces between epithelial cells of the junctional epithelium. As a result, inflammation occurs.[4][5][6]

In clinical gingival health, homeostasis occurs because resident biofilm of plaque bacteria and the host defences (symbiosis) results in a dynamic equilibrium with oral hygiene practices such as brushing and flossing. Therefore, despite having clinical gingival health, a low level of inflammatory infiltrate, consisting of neutrophils, B Cell Lymphocytes and macrophages, is always present in the connective tissue underlying the junctional epithelium. Essentially, this means that histologically, there will always be an inflammatory reaction to bacteria from plaque.

The constant low-level inflammatory reaction in the connective tissue underlying the junctional epithelium also results in the formation of the Gingival Crevicular Fluid (GCF). The Gingival Crevicular Fluid (GCF) is a serum like fluid that is formed from the post capillary venules of the Dentogingival Plexus which is a dense network of blood vessels within the gingival connective tissue that is sub-adjacent to the junctional epithelium.

The Gingival Crevicular Fluid (GCF) is made up of various components of cells and blood. These include defence cells and proteins such as Neutrophils, Antibodies and Complement, and various plasma protein. With the outflow of the Gingival Crevicular Fluid (GCF) into the gingival sulcus, at a rate of approximately 0.2ul per hour, that significantly increases with the presence of periodontal disease, this produces a “washing effect” that aids in preventing bacterial invasion.

Legend:

- Tooth Dentine

- Tooth Enamel

- Infiltrated Connective Tissue (is this the pink dots – surely they should be under the junctional epithelium rather than at the gingival crest

- Gingival Sulcus

- Microbial Colonization

- Dental Plaque and Biofilm

- Junctional epithelium: Base of Gingival Sulcus

Microbiology

The environment of the gingival sulcus is unlike any other location within the mouth.[7] The ecosystem of the gingival sulcus is more anaerobic, and the site is filled with Gingival Crevicular Fluid (GCF). In the presence of periodontal disease, the gingival sulcus becomes a periodontal pocket and the oxidation reduction potential will decrease to low levels as the site is very anaerobic. At the same time, the gingival crevicular fluid would have increased by 147% when gingivitis is present and would have increased by up to 30-fold where periodontitis is present. While gingival crevicular fluid provides for the cellular defence and humoral factors to combat against the microbial insult, the gingival crevicular fluid also deliver novel substrates, in the form of proteins and glycoproteins, for bacterial metabolism. These include haeme containing molecules and iron, such as haemoglobin and transferrin. Dissimilarly to dental caries, many bacteria associated to periodontal disease cannot metabolise carbohydrates for energy (they are asaccharolytic) and are proteolytic too.

One effect of proteolysis is that the pH of the gingival pocket with periodontal disease will increase and becomes slightly alkaline at around a pH level of 7.4 – 7.8 as compared to relatively neutral pH values, around a pH level of 6.9, when the gingival is healthy. In alkaline growth conditions, the enzyme activity and growth activity of periodontal pathogens, like Porphyromonas gingivalis. Similarly, during inflammation, slight increase in temperature of the periodontal pocket will occur too. The changes in the ecology of the gingival sulcus impacts gene expression and changes the competitiveness of periodontal pathogens like Porphyromonas gingivalis. Hence, the growth of proteolytic and Gram-Negative Anaerobes (most of the time) will be favoured by fluctuating homeostasis, the natural balance, of the subgingival microflora.

Extra attention must be given to maintain the feasibility of the obligately anaerobic species when trying to find out the microflora of a periodontal pocket or gingival sulcus during the sample collection, dispersing, diluting and cultivation phase of the sample. In a perfect scenario, the sample should be taken as close to the expanding front of the lesion as possible to exclude any organisms which are not involved in tissue destruction and to achieve a clear connection between the disease activity and specific bacteria. The sample should also be taken from the base of the periodontal pocket. Most of the time, it is challenging to determine periodontal diseases accurately because not all studies are comparing pathological conditions which are undistinguishable.

Pathology

When the sulcular depth is chronically in excess of three millimeters, regular home care may be insufficient to properly cleanse the full depth of the sulcus, allowing food debris and microbes to accumulate, forming dental biofilm. This poses a danger to the periodontal ligament (PDL) fibers that attach the gingiva to the tooth. If accumulated microbes remain undisturbed in a sulcus for an extended period of time, they will penetrate and ultimately destroy the delicate soft tissue and periodontal attachment fibers. If left untreated, this process may lead to a deepening of the sulcus, recession, destruction of the periodontium, including the bony tooth socket, tooth mobility, and tooth loss.[8] A periodontal pocket is a dental term indicating the presence of an abnormally deepened gingival sulcus.

References

- ↑ Joplin RE, Davis SM (2011-03-02). "The Anatomical Basis of Dentistry. By Bernard Liebgott. Elsevier, 2009. ISBN 9780323068079". Book review. Dental Update. 38 (2): 135. doi:10.12968/denu.2011.38.2.135. ISSN 0305-5000.

- ↑ Chatterjee K (2006). "Eruption and Shedding of Tooth". Essentials of Oral Histology. Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers (P) Ltd. p. 146. doi:10.5005/jp/books/10289_12. ISBN 978-81-8061-865-9.

- ↑ "Publications - British Society of Periodontology". www.bsperio.org.uk. Retrieved 2020-02-20.

- ↑ Lang NP, Bartold PM (June 2018). "Periodontal health". Journal of Clinical Periodontology. 45 Suppl 20 (S20): S9–S16. doi:10.1111/jcpe.12936. PMID 29926485.

- ↑ Chapple IL, Mealey BL, Van Dyke TE, Bartold PM, Dommisch H, Eickholz P, et al. (June 2018). "Periodontal health and gingival diseases and conditions on an intact and a reduced periodontium: Consensus report of workgroup 1 of the 2017 World Workshop on the Classification of Periodontal and Peri-Implant Diseases and Conditions". Journal of Clinical Periodontology. 45 Suppl 20 (S20): S68–S77. doi:10.1111/jcpe.12940. PMID 29926499.

- ↑ Hand AR (2015-01-20). Fundamentals of oral histology and physiology. ISBN 978-1-118-34291-6. OCLC 913507223.

- ↑ Marsh P. Marsh and Martin's oral microbiology. ISBN 978-0-7020-6174-5. OCLC 953863965.

- ↑ Nanci A (2007). Ten Cate's Oral Histology. Elsevier. p. 3.

Further reading

- Scheid RC (2012). Woelfel's Dental Anatomy. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 200. ISBN 978-1-60831-746-2.