The Goos–Hänchen effect (named after Hermann Fritz Gustav Goos (1883 – 1968)[1] and Hilda Hänchen (1919 – 2013) is an optical phenomenon in which linearly polarized light undergoes a small lateral shift when totally internally reflected. The shift is perpendicular to the direction of propagation in the plane containing the incident and reflected beams. This effect is the linear polarization analog of the Imbert–Fedorov effect.

Acoustic analog of the Goos–Hänchen effect is known as Schoch displacement.[2]

Description

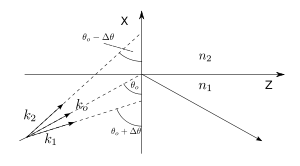

This effect occurs because the reflections of a finite sized beam will interfere along a line transverse to the average propagation direction. As shown in the figure, the superposition of two plane waves with slightly different angles of incidence but with the same frequency or wavelength is given by

where

and

with

- .

It can be shown that the two waves generate an interference pattern transverse to the average propagation direction,

and on the interface along the plane.

Both waves are reflected from the surface and undergo different phase shifts, which leads to a lateral shift of the finite beam. Therefore, the Goos–Hänchen effect is a coherence phenomenon.

Research

This effect continues to be a topic of scientific research, for example in the context of nanophotonics applications. A negative Goos–Hänchen shift was shown by Walter J. Wild and Lee Giles.[3] Sensitive detection of biological molecules is achieved based on measuring the Goos–Hänchen shift, where the signal of lateral change is in a linear relation with the concentration of target molecules.[4] The work by M. Merano et al.[5] studied the Goos–Hänchen effect experimentally for the case of an optical beam reflecting from a metal surface (gold) at 826 nm. They report a substantial, negative lateral shift of the reflected beam in the plane of incidence for a p-polarization and a smaller, positive shift for the s-polarization case.

Generation of giant Goos-Hänchen shift

It is known that the value of lateral position Goos-Hänchen shift is only 5-10 μm at a total internal reflection interface of water and air, which is very difficult to be experimentally measured.[6][7] In order to generate a giant Goos-Hänchen shift up to 100 μm, surface plasmon resonance techniques were applied based on an interface between metal/dielectric.[8][9][10] The electrons on the metallic surface are strongly resonant with the optical waves under specific excitation condition. The light has been fully absorbed by the metallic nanostructures and create an extreme dark point the resonance angle. Thus, a giant Goos-Hänchen position shift is generated by this singular dark point at the totally internally reflected interface.[11] This giant Goos-Hänchen shift has been applied not only for highly sensitive detection of biological molecules but also for the observation of Photonic Spin Hall Effect that are important in quantum information processing and communications.[12][13]

References

- ↑ de:Fritz Goos

- ↑ Atalar, Abdullah (1978). "An angular‐spectrum approach to contrast in reflection acoustic microscopy". Journal of Applied Physics. 49: 5130–5139. doi:10.1063/1.324460.

- ↑ Wild, Walter J.; Giles, C. Lee (1982). "Goos-Hänchen shifts from absorbing media" (PDF). Physical Review A. 25 (4): 2099–2101. Bibcode:1982PhRvA..25.2099W. doi:10.1103/physreva.25.2099.

- ↑ Jiang, L.; et al. (2017). "Multifunctional hyperbolic nanogroove metasurface for submolecular detection". Small. 13 (30): 1–7. doi:10.1002/smll.201700600. PMID 28597602.

- ↑ M. Merano; A. Aiello; G. W. ‘t Hooft; M. P. van Exter; E. R. Eliel; J. P. Woerdman (2007). "Observation of Goos Hänchen Shifts in Metallic Reflection". Optics Express. 15 (24): 15928–15934. arXiv:0709.2278. Bibcode:2007OExpr..1515928M. doi:10.1364/OE.15.015928. PMID 19550880. S2CID 5108819.

- ↑ A.W. Snyder (1976). "Goos-Hänchen shift". Applied Optics. 15 (1): 236–238. Bibcode:1976ApOpt..15..236S. doi:10.1364/AO.15.000236. PMID 20155209.

- ↑ R.H. Renard (1964). "Total reflection: A new evaluation of the Goos–Hänchen shift". Journal of the Optical Society of America. 54 (10): 1190–1197. doi:10.1364/JOSA.54.001190.

- ↑ X. Yin (2006). "Goos-Hänchen shift surface plasmon resonance sensor". Applied Physics Letters. 89 (26): 261108. Bibcode:2006ApPhL..89z1108Y. doi:10.1063/1.2424277.

- ↑ A.D. Parks (2015). "Weak value amplification of an off-resonance Goos–Hänchen shift in a Kretschmann–Raether surface plasmon resonance device". Applied Optics. 54 (18): 5872–5876. Bibcode:2015ApOpt..54.5872P. doi:10.1364/AO.54.005872. PMID 26193042.

- ↑ S. Zeng (2020). "Plasmonic metasensors based on 2D hybrid atomically thin perovskite nanomaterials". Nanomaterials. 19 (7): 1289–96. doi:10.3390/nano10071289. PMC 7407500. PMID 32629982.

- ↑ Y. Wang (2021). "Targeted sub-attomole cancer biomarker detection based on phase singularity 2D nanomaterial-enhanced plasmonic biosensor". Nano-Micro Letters. 13 (1): 96–112. arXiv:2012.07584. Bibcode:2021NML....13...96W. doi:10.1007/s40820-021-00613-7. PMC 7985234. PMID 34138312. S2CID 229156325.

- ↑ K.Y. Bliokh (2015). "Spin–orbit interactions of light". Nature Photonics. 9 (12): 796–808. arXiv:1505.02864. Bibcode:2015NaPho...9..796B. doi:10.1038/nphoton.2015.201. S2CID 118491205.

- ↑ X. Yin (2015). "Photonic spin Hall effect at metasurfaces". Science. 339 (6126): 1405–1407. doi:10.1126/science.1231758. PMID 23520105. S2CID 5740891.

- Books

- de Fornel, Frédérique (2001). Evanescent Waves: From Newtonian Optics to Atomic Optics. Berlin: Springer. pp. 12–18. ISBN 9783540658450.

- Goos, F.; Hänchen, H. (1947). "Ein neuer und fundamentaler Versuch zur Totalreflexion". Annalen der Physik. 436 (7–8): 333–346. Bibcode:1947AnP...436..333G. doi:10.1002/andp.19474360704.

- Delgado, M.; Delgado, E. (2003). "Evaluation of a total reflection set-up by an interface geometric model". Optik. 113 (12): 520–526. Bibcode:2003Optik.113..520D. doi:10.1078/0030-4026-00205.