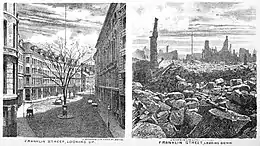

The Great Boston Fire of 1872 was Boston's largest fire, and still ranks as one of the most costly fire-related property losses in American history. The conflagration began at 7:20 p.m. on Saturday, November 9, 1872, in the basement of a commercial warehouse at 83–87 Summer Street.[1] The fire was finally contained 12 hours later, after it had consumed about 65 acres (26 ha) of Boston's downtown, 776 buildings and much of the financial district, and caused $73.5 million in damage (equivalent to $1.609 billion in 2022).[2][3] The destruction to the buildings was valued at $13.5 million and the personal property loss was valued at $60 million.[1] In the end, at least 30 people died, including 12 firefighters.[4]

Underlying causes

Building practices

In 1872, there was no strictly enforced building code in Boston. The streets were narrow and the buildings were close together. Many of the buildings were too tall for fire ladders to reach the upper levels, and the pressure from the fire hoses was often insufficient to extinguish flames on the roofs of the buildings. Thus, the fire could spread from rooftop to rooftop, and across narrow streets. Many of the affected buildings were made of brick and stone, but with wooden framing.[1] Also, wooden mansard roofs were a common architectural trend of the time period. The steep pitch of a mansard roof allows for more storage in the upper levels of a building. However, these roofs are flammable due to their wooden construction. Additionally, the warehouses of downtown Boston commonly stored dry materials in the eaves of the roofs, increasing the flammability. Merchandise stored in the attics of warehouses was not considered taxable inventory.[5]

Insurance

Building owners in Boston had few incentives to implement fire-safety measures. Buildings were often insured above value or at full value. Arson to gain insurance money was not uncommon.[4]

Fire alarm boxes

In 1852, Boston became the first city in the world to install telegraph-based fire alarm boxes.[6] The boxes served as a fire warning system. If the lever inside of the alarm box was pulled, the fire department was notified, and the alarm could be traced back to the box via a coordinate system so that firefighters were dispatched to the correct location. All of the fire alarm boxes were kept locked from when the system was installed in 1852 until after the Great Fire of 1872 to prevent false alarms. A few citizens in each area of Boston were given a key to the boxes, and all other citizens had to report fires to the key-holders, who could then alert the fire department.[7] In 1872, witnesses watched the fire spread before the area's key-holder was found and could unlock the alarm box to alert the Boston Fire Department. Twenty minutes after the fire was first noticed, firefighters arrived on the scene.[1]

Water infrastructure

John Damrell, Boston Fire Department's chief engineer at the time, had told Boston officials that the existing water infrastructure was inadequate. He was told not to "magnify the needs of his department" after requesting funding for water infrastructure repairs.[8] The existing water main pipelines were old and leaky, making the pressure in the pipes lower than acceptable. The pressure was so low that the pipes could not produce enough force to reach the top floors and roofs of newer buildings.[5] There were not enough hydrants throughout the city to adequately cover the surrounding buildings. As the fire spread, firefighters struggled to find hydrants with adequate water pressure. Also, the fire hydrant couplings were not standardized within Boston, making it more difficult for firefighters to connect their hoses and related equipment.

Horse sickness

The Boston fire department used horses to pull fire engines, hoses, and ladders.[9] At the time of the 1872 fire in early November, the northeast United States was experiencing an epizootic equine flu that affected and weakened the horses.[9][10] When Damrell heard of the horse sickness he preemptively hired an additional 500 men to replace the horsepower that would typically haul the engines and other equipment to the sites of fires.[2] After the fire, the city commission in charge of investigating the fire concluded that the response time of the fire department was only delayed by a few minutes in the absence of the horses.[11]

Similarities to Great Chicago Fire

In 1871, Chicago suffered massive destruction and an estimated 300 casualties in the Great Chicago Fire. Damrell, along with fire chiefs from various large cities, traveled to Chicago after the fire in an attempt to learn from the city's mistakes. Like Boston, Chicago buildings were made primarily of wood and building codes were not enforced, making the densely developed neighborhoods susceptible to fire. General Phil Sheridan, in charge of military relief in Chicago post-fire, did not condemn the city's use of gunpowder to blow up buildings to create firebreaks. In theory, a firebreak creates a gap in flammable material that serves as a barrier where the fire will run out of "fuel" to spread any further. However, many fire chiefs from Southern cities were firmly opposed to gunpowder-created firebreaks after having seen the destruction they caused in the Civil War.[12] Damrell returned to Boston and continued to request funding for improved water infrastructure and fire equipment.[13]

Events of the fire

Experts have deduced that the fire began in the basement of a warehouse on the corner of Kingston Street and Summer Street, at approximately 83–85 Summer Street.[1] In this particular area, most of the buildings were dedicated to retail or used as warehouses. The warehouse that first caught fire housed dry goods. From the basement, the flames spread to the wooden elevator shaft in the center of the building and moved up the floors, fueled by the flammable fabrics in storage. Finally, the building's wooden mansard roof caught on fire and the flames were able to spread from rooftop to rooftop down the street. The heat became so intense that stone facades shattered.[14] The fire spread through most of Boston's financial district which became known as the "burnt district." The glow of the fire was noted in ships' logs by sailors off the coast of Maine.

.tiff.jpg.webp)

Timeline of events

Source:[14]

- 7 pm, November 9: the fire begins in the basement of a warehouse.

- 7:24 pm, November 9: first alarm is received from Box 52.[15]

- 8 pm, November 9: all 21 of Boston's fire engines are at the scene of the fire.

- 10 pm, November 9: the fire spread to a three block radius.

- 12 am, November 10: the fire spread to a five block radius.

- 4 am, November 10: the fire spread to the waterfront, destroying wharves and docked boats.

- 6 am, November 10: the fire reached Washington Street and spread through the center of downtown.

- midday, November 10: the fire is stopped and contained before it destroys Old South Meeting House.

Fire department response

At 7:24 pm, the first alarm was received from Box 52 at the corner of Summer Street and Lincoln Street. The first fire engine to arrive was Engine Co. 7 from a station at 7 East Street. The first water on the fire came from Hose Company 2 of Hudson Street.[1] By 8 pm, all of Boston's twenty-one engine companies were fighting the fire.[14] Telegraphs were sent to surrounding towns requesting help, but the messages were delayed due to most telegraph offices already having closed for the night. Eventually, support arrived from fire departments in every state of New England, except Vermont. Of these were two Amoskeag Steamers from Manchester, New Hampshire. One was the first Amoskeag ever constructed (serial number 1), owned by the Manchester Fire Department; the other was the first self-propelled Amoskeag that the manufacturer sent down. Impressed with its performance, Boston purchased the self-propelled steamer after the fire, the first one in use in the country.[16]

Crowd control

During the fire, the narrow streets of Boston were packed with firefighters and their equipment as well as crowds of people. As building owners raced to retrieve valuables from their burning properties, looters ran in after them to collect whatever was left behind. Because the affected area was mostly commercial and not residential, spectators came from residential neighborhoods to watch the fire spread. Some historians estimate that over 100,000 bystanders watched the fire spread.[2] The firefighters had to both extinguish the flames and keep people back from danger.

Gas lines

Gas supply lines connected to street lamps and used for lighting in buildings could not be shut off promptly. The gas still running through the lines served as fuel to the fire. Many of Boston's gas lines exploded due to the fire.[2]

Use of explosives

As the fire spread, citizens asked Mayor William Gaston to authorize the use of gunpowder to blow up buildings in the path of the fire to create a firebreak.[1] Mayor Gaston approved the creation of firebreaks and groups of citizens began packing buildings with gunpowder kegs. However, the firebreaks were not effective. Instead, they caused injury to the citizens involved and the flaming debris from the exploded buildings spread to surrounding buildings. Eventually, Damrell had to force citizens to stop using gunpowder.[5]

Conclusion

Citizens and firefighters alike worked to stop the fire. Along Washington Street, wet blankets and rugs were said to have been used to cover buildings to prevent the fire from spreading to the Old South Meeting House, the church in which the Boston Tea Party was planned. Some citizens and firefighters climbed to the roof of the meeting house to put out sparks.[8] The efforts to save this historic landmark finally halted the fire at the corner of Washington and Milk Streets, around midday on November 10.

Aftermath

Notable buildings destroyed

- The Boston Globe, newspaper[17]

- The Boston Herald, newspaper[17]

- Shreve, Crump & Low, a jewelry store, relocated from its original workshop to 225 Washington Street after the fire.[17]

- Carter's Ink Company[18]

- Rice & Hutchins, a shoe manufacturer and distributor at 125 Summer St.[18]

- Trinity Church, 18th century Anglican colonial period church on Summer Street.[18]

Rebuilding

Following the fire, a citizen-formed committee urged Boston to restructure the layout of roadways in the damaged areas. Boston officials approved of this proposal, and many downtown streets were re-established to be wider and straighter.[9] Most notably, Congress Street, Federal Street, Purchase Street, and Hawley Street were widened. The restructuring allotted space to establish Post Office Square at the intersection of Milk, Congress, Pearl, and Water Streets. Some of the rubble from destroyed buildings was moved into the harbor to expand Atlantic Avenue.[4] Because over-insurance of buildings was common, many businesses had enough insurance money to begin rebuilding soon after the fire. In less than two years, Boston's financial district was rebuilt.[2]

Economic effects

In the rebuilding that followed the fire, land values of the "burnt district" increased, according to a study in American Economic Review in 2017.[19] The forced reconstruction of the financial district brought about widespread, simultaneous building upgrades and updates, and many properties were rebuilt to suit the commercial nature of the district.[20][21] The widening of roads and re-assembly of land plots into larger parcels also contributed to the rise in land values.

John Stanhope Damrell

A new committee, the Fire Commission was established to oversee the Boston Fire Department and investigate the fire of 1872. John Damrell resigned from his position as chief engineer in 1874 in the wake of the Fire Commission's investigation.[13] He had served as chief engineer for eight years and worked as a professional firefighter in Boston since 1858.[22] In 1874, Boston began replacing and repairing its water mains, one of Damrell's main causes during his career.[2] Damrell continued his career in firefighting and public safety. In 1873, he founded the National Association of Fire Engineers (NAFE, now called the International Association of Fire Chiefs, IAFC) and became the organization's first president.[22] He also served as a building inspector for the city of Boston.[8]

Building code and inspection

While Damrell served as president of NAFE, the association published a list of eight fire safety concerns in building construction.[23]

- Flammable and combustible building materials

- Excessive height buildings, beyond the reach of ground ladders

- Fire escapes

- Water supply

- Space between buildings

- Corridors and open stairways

- Fire alarms

- Fire department

In 1877, Damrell was appointed Boston's building commissioner. He served the Department of Building Inspection for 25 years, until his son succeeded him.[14] At the 20th Annual Convention of NAFE in 1892, Damrell is credited for Boston's formally established limits of building height and area. At the time, Boston was the only American city with these limitations.

In 1884, Damrell petitioned the National Association of Fire Engineers to create a more formalized building code during his presentation of Building Code Report at a NAFE convention.[22]

In 1891, The National Association of Commissioners and Inspectors of Public Buildings (NACIPB) was established by Damrell, and he served as the first president. He served a second term as president when he was re-elected at the organization's annual conference in 1894.[22]

A standardized building code wasn't established until 1905, the year of Damrell's death, when the National Board of Fire Underwriters published its National Building Code.[24]

Remembrance

At the corner of Kingston and Summer Streets, a plaque was installed by The Bostonian Society to mark the start of the fire.[25]

Old South Meeting House recognized the 138th anniversary of the fire in 2010 by displaying a partially restored Kearsarge fire engine.[14]

Harvey W. Wiley took part in fighting the fire while he was a student at Harvard University. He later wrote about it in his autobiography.

Author Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. watched the fire from his home on Beacon Hill. He wrote a poem about the event called "After the Fire".

Image gallery

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Great Boston Fire of 1872 – Boston Fire Historical Society". Boston Fire Historical Society. Retrieved November 3, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Great Fire Devastates Boston". www.massmoments.org. November 9, 2005. Retrieved November 3, 2018.

- ↑ Johnston, Louis; Williamson, Samuel H. (2023). "What Was the U.S. GDP Then?". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved November 30, 2023. United States Gross Domestic Product deflator figures follow the Measuring Worth series.

- 1 2 3 "The Great Boston Fire of 1872 – New England Historical Society". www.newenglandhistoricalsociety.com. March 9, 2016. Retrieved October 26, 2018.

- 1 2 3 Docema. "Boston 1872 Fire". www.boston1872.docema.com. Retrieved October 26, 2018.

- ↑ "For Fire Alarms, Boston Still Relies on … the Telegraph?!". Boston.com. October 7, 2014. Retrieved October 26, 2018.

- ↑ "Hardware – Boston Fire Historical Society". Boston Fire Historical Society. Retrieved October 26, 2018.

- 1 2 3 Herwick, Edgar B. (November 20, 2015). "The Great Fire That Leveled Boston And Ignited John Damrell's Safety Crusade". News. Retrieved October 24, 2018.

- 1 2 3 Yee, Erica (November 9, 2017). "When an 1872 fire ravaged downtown Boston". Boston.com. Retrieved November 3, 2018.

- ↑ "The Horse Flu Epidemic That Brought 19th-Century America to a Stop". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved February 8, 2021.

- ↑ Report of the Commissioners appointed to investigate the cause and management of the great fire in Boston. Boston: Rockwell & Churchill. 1873. p. 535. hdl:2027/yale.39002013462230.

- ↑ "The National Association of Fire Engineers". www.fireengineering.com. August 11, 1888. Retrieved November 2, 2018.

- 1 2 Hensler, Bruce (October 21, 2015). "6 pioneers of fire-behavior research". Fire Chief. Retrieved November 1, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "NFPA Journal – Boston Fire Trail, May June 2011". www.nfpa.org. Retrieved October 31, 2018.

- ↑ "Storz Couplings— an old idea that's still going strong". Fire Engineering. 137 (11). November 1, 1984.

- ↑ Steve Pearson. "Interesting facts about the department". Manchesterfirehistory.com. Archived from the original on July 14, 2011. Retrieved January 11, 2011.

- 1 2 3 Southwick, Al. "Al Southwick: Boston fires – 2019 and 1872". telegram.com. Retrieved February 8, 2021.

- 1 2 3 "Report of the Great Boston Fire". The Boston Globe. November 11, 1972. Retrieved February 4, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Hornbeck, Richard; Keniston, Daniel (June 1, 2017). "Creative Destruction: Barriers to Urban Growth and the Great Boston Fire of 1872". American Economic Review. 107 (6): 1365–1398. doi:10.1257/aer.20141707. ISSN 0002-8282.

- ↑ Sammarco, Anthony Mitchell (2002). Boston's Financial District. Arcadia Publishing. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-7385-1125-2.

- ↑ Badger, Emily; Bui, Quoctrung (July 10, 2020). "Riots Long Ago, Luxury Living Today". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 8, 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 Docema. "Timeline of John S. Damrell". www.boston1872.docema.com. Retrieved October 26, 2018.

- ↑ Havel, Gregory (November 16, 2015). "Fire Code: Construction Concerns: Pre-Code Buildings". www.fireengineering.com. Retrieved November 2, 2018.

- ↑ Murphy, Jack J. (January 1, 2007). "Code Development: Whose Battlefield is this?". www.fireengineering.com. Retrieved November 2, 2018.

- ↑ "Great Boston Fire Site". Read the Plaque. Retrieved November 2, 2018.

Further reading

External links

- Boston Public Library on Flickr. Collection of images related to the fire.

- Flash Map of Fire from MapJunction

- Boston Fire Department History

- Boston, MA The Great Fire, Nov 1872, GenDisasters.com

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)