Grianán of Aileach | |

The Grianan of Aileach is in the Republic of Ireland (grey), near the border with Northern Ireland (cream) | |

| Alternative name | Greenan Ely |

|---|---|

| Location | County Donegal, Ireland |

| Coordinates | 55°01′26″N 7°25′39″W / 55.0238°N 7.427592°W |

| Type | Ringfort |

| Height | 5 metres (16 ft) |

| History | |

| Material | Stone |

| Founded | 6th century CE or earlier |

| Abandoned | 12th century CE |

| Periods | Iron Age–Middle Ages |

| Cultures | Gaelic |

| Associated with | Kings of Ailech |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 1830s; 1870s |

| Archaeologists | George Petrie; Walter Bernard |

| Public access | Yes |

| Official name | Grianan of Aileach |

| Reference no. | 140[1] |

The Grianan of Aileach (/ˌɡriːnən əv ˈæljə(x)/ GREE-nən əv AL-yə(kh); Irish: Grianán Ailigh [ˌɟɾʲiənˠaːnˠ ˈalʲiː]), sometimes anglicised as Greenan Ely or Greenan Fort, is a hillfort atop the 244 metres (801 ft) high Greenan Mountain at Inishowen in County Donegal, Ireland. The main structure is a stone ringfort, thought to have been built by the Northern Uí Néill, in the sixth or seventh century CE;[2] although there is evidence that the site had been in use before the fort was built. It has been identified as the seat of the Kingdom of Ailech and one of the royal sites of Gaelic Ireland. The wall is about 4.5 metres (15 ft) thick and 5 metres (16 ft) high. Inside it has three terraces, which are linked by steps, and two long passages within it. Originally, there would have been buildings inside the ringfort. Just outside it are the remains of a well and a tumulus.

By the 12th century, the Kingdom of Ailech had become embattled and lost a fair amount of territory to the invading Normans. According to Irish literature, the ringfort was mostly destroyed by Muirchertach Ua Briain, King of Munster, in 1101. Substantial restoration work was carried out in 1870. Today, the site is protected as a national monument and is a tourist attraction.

Description and interpretation

_(14779372521).jpg.webp)

The Grianán is located on the western edge of a small group of hills that lie between the upper reaches of Lough Swilly and Lough Foyle. Although the hill is comparatively not that high, the summit dominates the neighbouring counties of Londonderry, Donegal and Tyrone. Located at the edge of the Inishowen peninsula, it is 11.25 kilometres (7 mi) northwest of the ecclesiastical site of Derry. The histories of the sites are closely linked. There is much legend and historical material related to the Grianán of Aileach. The Irish annals record its destruction in 1101. The main monument on the hill is a stone cashel, restored in the nineteenth century, but probably built in the eighth century CE. The summit's use as an area of settlement may go back much further. A tumulus at the Grianán may date back to the Neolithic age. A covered well was found near the cashel in the early nineteenth century.

Irish antiquarian George Petrie first surveyed the Grianán of Aileach in the 1830s. At this time the cashel was nothing more than a mere ruin. He gives a description of the hill and the monument. The eastern ascent of the hill is described as gradual but within 30 metres (98 ft) of the top, it terminated in a circular apex. An ancient road between two ledges of natural rock led to the summit. The cashel was surrounded by three concentric ramparts. Petrie suggests that, in the fashion of other monuments of this type such as Emania, the whole hill may have been enclosed by many other ramparts. There is no physical or historical evidence for this. The ramparts that remained were made of earth and stone and follow the natural form of the hill with an irregular circular pattern. They ascend above each other creating levelled terraces. The circular apex of the hill within the outermost enclosure contains about 2.2 hectares (5.4 acres), within the second about 1.6 hectares (4.0 acres) and within the third about 4 hectares (9.9 acres). Currently, the innermost bank is very low, worn and heather-covered but traceable for almost its entire circuit. The other two banks are in a similar state but are untraceable for long sections. Between the inner most rampart and the cashel, the road dwindles in its width and curves slightly to the right. This "path" was strengthened on either side by walls. At the time of the survey only the foundation stones of these walls remained. Petrie's plan of the site shows a line of stones leading up to the entrance. These are now gone.

The ruins of the cashel itself are described as being a circular wall enclosing an area of 23.6 metres (77 ft) in diameter. The wall had a height of 1.8 metres (5 ft 11 in) with a breadth varying from 4.6 metres (15 ft) to 3.5 metres (11 ft). While not perpendicular, it had an inclination inwards indicating its similarity to most other Irish stone forts. Petrie suggests that it was probably originally between twice and four times as high as it was when he surveyed it. 1.5 metres (4 ft 11 in) up on the interior side of the wall, the thickness was 0.76 metres (2 ft 6 in) due to the presence of terracing. The terrace is reached by flights of steps on either side of the entrance gateway. Fallen stones had covered any other existing stairs. Petrie suggests that there were originally three or four such terraces ascending to the top of the wall. On each side of the entranceway, there are "galleries" within the wall. Their precise purpose is not clear and they do not connect with the entrance. These two wall-passages, one on the south and another from the northeast run towards the gateway, but stop short. Near the north end of the south passage is a small recess in its west wall. At the south end of the north passage there is a seat-stone.

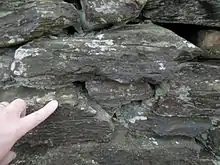

The current hillfort, after the restoration of 1874–1878, is substantially different but much of the old structure remains intact. During the restoration, it was found that parts of the original drystone masonry had been preserved under the collapse. The workers marked, in tar, the undisturbed portions of the cashel and used the collapsed stone to build on this foundation. They supplemented these with other stones from the area to replace those 'removed by King Murdoch O'Brien in 1101'. The internal diameters of the cashel are 23.6 metres north to south and 23.2 metres (76 ft) east to west. The lintel-covered entrance is 4.65 metres (15.3 ft) long, 1.12 metres (3 ft 8 in) wide and 1.86 metres (6 ft 1 in) metres high. Before the restoration, the gateway's lintel was not in place. It was1.3 metres (4 ft 3 in) wide and 1.2 metres (3 ft 11 in) high. It leads into the fort from the east. Slight recesses on either side of the entrance way have been filled in. They were probably to allow double leaves of an original doorway to fold flush against the wall. The interior rises in three terraces accessible by stairways which are previously mentioned. The outer wall is a dry-stone construction. On each side of the entranceway, there are "galleries" within the wall. Their precise purpose is not clear and they do not connect with the entrance. These two wall-passages, one on the south and another from the northeast run towards the gateway, but stop short. The south wall passage entrance is 45 centimetres (18 in) wide, 69 centimetres (27 in) high and 1.4 metres (4 ft 7 in) long. It turns through a right angle where it becomes 50 centimetres (20 in) wide,85 centimetres (33 in) high and 20.4 metres (67 ft) long. Near the north end there is a recess on the west side 50 centimetres (20 in) wide, 1 metre (3 ft 3 in) and 75 centimetres (30 in) deep. The northeast gallery entrance is 65 centimetres (26 in) wide, 97 centimetres (38 in) high and 1.55 metres (5 ft 1 in) long. It meets the main part of the passage in a T-junction. To the north, the passage is 70 centimetres (28 in) wide, 1.3 metres (4 ft 3 in) high and 2.5 metres (8 ft 2 in) long. To the south, the passage is 60 centimetres (24 in) wide, 1.4 metres (4 ft 7 in) high and 8.6 metres (28 ft) long. Near the north of end of the south passage is a small recess in its west wall. At the south end of the north passage there is a seat-stone. The interior of the cashel is fairly level but Petrie recorded the remains of a small oblong church measuring 5 metres (16 ft) by 4.3 metres (14 ft). The walls were 61 centimetres (24 in) thick and not more than 62 centimetres (24 in) high. The structure was constructed of mortar but nothing remains of it today. A drain runs through the cashel wall at ground level on the northwest side. It leads from a midden in the western side of the enclosure that was 1.7 metres (5 ft 7 in) in diameter and one foot deep.

There are many clues that the Grianán of Aileach is a multi-period site. Brian Lacy suggests that the earthen banks surrounding the fort probably represent the defences of a hillfort of the late Bronze Age or Iron Age. Between the two outer banks on the south side of the hill, is the formerly covered spring well which is dedicated to St Patrick. Petrie describes the tumulus, between the second and third wall, as being a small mound surrounded by a circle of ten stones. These stones were laid horizontally and converged towards the centre. In Petrie's time, the mound had been excavated but nothing to explain its meaning was discovered. It was subsequently destroyed but its former position is marked by a heap of broken stones.

During the excavation work of the 1870s, Bernard documented the discovery of many artefacts. Behind a niche in the doorway, a large stone 40 centimetres (16 in) wide was found. It had a round hole in the centre, 7.6 centimetres (3 in) deep and 3.8 centimetres (1.5 in) in diameter. A rotten piece of wood was found in the hole. Bernard was unable to decipher its use suggesting only that it could have been a sundial.

Bernard discovered many animal bones including sheep, cattle, goats and birds. He found stone items including "sling-stones", "warrior's clubs" and a "sugar-loaf-shaped stone with a well-cut base" 25 centimetres (10 in) long, 38 centimetres (15 in) round base, 36 centimetres (14 in) round centre and 25 centimetres (10 in) round top.

The most interesting stone object was "a slab of sandstone, chequered into thirty-six squares", which Lacy believed to be some kind of gaming board. Among the miscellaneous items found were a plough socket, an iron ring, some coins and a bead.

Reconstruction

Between 1835 and 1874, the hillfort was going through a state of reconstruction under Walter Bernard of Derry.[3] Bernard, before construction, only had evidence of the base layer of the monument, with other pieces still present being described as a ‘mere ruin.’ The height from the best surviving walls were given as approximately 6ft, whilst having an obvious batter, and sloping inwards like Staigue Fort in Kerry. From this, Bernard concluded that he would look to another monument for reference on design and scale: Staigue Fort in County Kerry in Ireland is where he deduced the architecture for the monument. This led him to reconstruct the cashel based on the architecture found in County Kerry rather than the county that the original site was in, which was County Donegal. The reconstruction by Bernard has impacted the site as it is a reconstruction done in a more modern time. The reconstruction resulted in poor and crude engineering, with the site left crumbling after being taken over by state care 30 years after the reconstruction. After a later investigation was completed, it was noted that during the reconstruction, Bernard did not have enough of the good-quality stone that he was using on site. The only way for the state to improve the structure is if they improve what Bernard had already built on top of it. This means that the architecture and what we see comes from a second-hand account of what Bernard thought Grianan of Aileach would have looked like from his deductions whilst looking at the Staigue Fort in Kerry.[3]

Morphology

The Grianán of Aileach, at its broadest description, is a ringfort. More precisely it is a multivallate cashel hillfort.

A ring fort can be described as a space, usually circular, surrounded by a bank and ditch or simply a rampart of stone. The bank is generally built by piling up inside the fosse the material obtained digging the latter. Ringforts vary considerably in size and style. In more elaborately defended examples, such as Aileach, the defences take up a much greater area than the enclosure itself.

Matthew Stout gives many examples of why the people who built these structures chose a circular formation. First of all, they had strategic advantages. Circular sites allowed for a broad perspective of the surrounding area and allowed the maximum area to be enclosed relative to the bank constructed. He also comes up with some much more metaphysical theories. He suggests that a circular formation linked the site and its occupants with the circular burial mounds of their ancestors. About a third of all Irish hillforts have mounds or cairns within them. The Aileach is no exception. He also puts forward the idea that a circular form was favoured because corners could act as a dwelling-place of evil spirits. He bases these claims on ethnographic comparisons.

Ringforts housed families of varying degrees of wealth, so that some of them are more impressive than others. Ringforts do not normally occupy dominant or commanding positions. The only exception to this are the ringforts built in areas of bad drainage where high places are the only suitable spots for habitation. Raftery names three monuments which he finds hard to categorise as being either a ringfort or a hillfort: Cahirciveen; Carraig Aille; and Lough Gur. While the places where they sit are areas of natural defence, they may have been built there for drainage purposes. The buildings themselves are not militaristic or defensive in themselves. They were probably family homesteads. The defining characteristic of hillforts is an inbuilt defensive nature.

Therefore, hillforts as a subcategory of the ringfort are defined by their location and style of construction. Hillfort consist of ‘large hilltop areas on which the summit is enclosed by one (univallate) or multiple ramparts (multivallate) of earth or stone’. A good example would be Dún Aengus on Inishmore. Its defensive nature is explicit due to the system of stone slabs, known as chevaux de frise, planted into the ground outside the fort structure itself.

The Grianán of Aileach, as described in the introductory section, is encircled by three enclosures and is therefore trivallate. The actual living space of ringforts often forms less than 60% of the total monument area. Contemporary law tracts described a king's principal dwelling to have been a univallate ringfort. Increasing a site's defences without a corresponding increase in its functional area demonstrates either a greater need for defence or a display of status. Therefore, a ring fort with two ramparts (bivallate) acts a status symbol. The rarity of trivallate hillforts, such as that at the Grianán, shows the importance and status of its occupants rather a need for defence.

Stout gives several examples to indicate their symbolic importance simply due to their impracticality as defensive structures. In general, they were little more than fences to prevent stock from straying and to protect against wild animals. As siege tools, they were useless. If anything they were built to repel cattle raids.This might not be the case with the Grianán of Aileach

While the original structure for which the ramparts were built does not exist any more, the cashel of Aileach, while formidable, was probably designed with less of a defensive function in mind but rather it was built as a symbol of royal power. Stone structures appear both eternal and immovable. The cashel was built on this site for the panoramic view rather than for defence. This could be seen as changing the visual emphasis of the ramparts from being defensive terraces to enclosures of royal power and influence.

Hillforts are known throughout western Europe but Irish hillforts were not as well developed and never attained the standard of the so-called Celtic Oppida of Continental Europe and Britain. They vary in size but are of a communal rather than single-family residence. Cashels (stone-built ringforts) tend to be much smaller than earthen examples. The average earthen ringfort has an internal diameter of 22 metres in south Donegal; cashels in the same area have an average internal diameter of 20 metres. The Grianán of Aileach, with an average internal diameter of 23.4 metres is larger than the latter and therefore this must be an indication of the wealth and importance of its inhabitants and perhaps it is also an indication of the size of its occupant population. Lacy suggests that the innovative nature of the stone fort of Aileach must have been an unusual site when it was first constructed. The names Garvan, Frigru/ Rigriu are found in many Irish authorities to be the names of the builders of Aileach. These characters are linked to the Formorians and therefore may be nothing more than mythological creations. Lacy believes that the builder may have been Áed Oirdnide, the victor at the battle of Cloíteach.

Chronology

It is widely accepted that most ringforts date from the Early Christian period. Finds from ringforts typically include items which date from the second half of the first millennium: a hand-made, bucket shaped pottery style called 'Souterrain Ware', which uses local clays and can be decorated or undecorated; glass beads; bone, bronze and iron pins; and artefacts of bone and metalwork. The artefacts, which Dr. Bernard found during his excavation of the cashel interior, seem to correspond to the above list of typical items. Indeed, in a recent publication, Brian Lacy comes up with an exact date for its construction which corresponds with this period. He argues that Aileach is the name of a specific site in antiquity and also the name of the Cenél nEógain 'homeland' kingdom of Inis Eogian, derived from the place now known as Elagh More or Elaghmore (Aileach Mór) in County Londonderry.

After the decisive battle of Cloítech in 789, when the Cenél nEógain won total control of the over-kingdom of the northern Uí Néill, the successful kings relocated to the Grianán, building it inside the pre-existing prehistoric hillfort as a visual symbol of their new mastery of all the landscape visible from that commanding view. Stout comes to the conclusion that the majority of Ireland's ringforts were occupied and constructed during a three hundred-year period from the beginning of the seventh century to the end of the ninth century AD.

Lacy concludes that Aileach was inhabited by the northern Ui Néill dynasty from 789 to about 1050. This was a period when many of the local kings in Ireland were moving to the towns founded by the Vikings or into more important ecclesiastical sites which by this time seemed to have been functioning as towns following the model set by the Vikings.

Distribution

Based on the morphology of hillforts, Raftery estimates that there are forty hillforts in Ireland. However, Lacy suggests that there are fifty forts remaining in Ireland. Multivallate hillforts are suggested to be confined to the West and South of the country; univallate forts are to be found in the north and east. The Grianán of Aileach is seen as an exception to this pattern. Raftery suggests that this simple division of distribution might be more blurred after further hillfort study and discovery.

The distribution of ringforts, in general, is much wider although we are a long way from knowing the exact number which still survive. Ringfort distribution is not even. Areas of low ringfort density correspond to intensely tilled, highly-Normanised areas. The assumption is that during the last eight centuries of tilling, many ringfort sites were destroyed. On this basis, Stout states that there are 45,119 ringforts in Ireland of which 41% have been positively identified as of March 1995. The mean density for Ireland as a whole is 0.55 per square kilometre. The density goes from below 0.20 per square kilometre in Donegal, Kildare and Dublin to above 1.0 per square kilometre in Roscommon, Limerick and Sligo. The regions of highest density are north Munster, east Connaught/ northwest Leinster and east Ulster. Areas of low density are in northwest Ulster and most of Leinster.

Donegal is an area of low ringfort concentration. It is therefore odd to find a hillfort of the size and scope of Aileach in this area. The ringfort density of Northwest Ulster as a whole is 0.16 per square kilometre. Northwest Ulster includes all of Donegal and the western portions of Londonderry and Tyrone. Ringforts are virtually absent from the areas of Derryveagh, the Blue Stacks, Slieve League and Inishowen. Ringforts are rarely found in similarly elevated areas of Londonderry and Tyrone, including the Sperrin Mountains and west of the Roe River. Due to the inhospitable nature of these areas due to blanket bogs and thin rock, they were sparsely populated. There were pockets of settlement such as southwest Donegal.

Ringforts can be found along the eastern slopes of Derryveagh Mountains, the Roe River valley and the Mourne River basin. Although some Early Christian settlement is present, the areas as a whole was relatively sparsely settled with ringforts despite the Mourne and Foyle river valleys being extremely suitable for agricultural exploitation. Other forms of secular settlement are also thinly distributed in the area although several souterrains have been found. Northwest Ulster maintained a low population density throughout the Early Christian Era. Barrett examined ringforts in southern Donegal. She identified 124 ringforts in an area reaching from Glen Head to Lough Ekse and south along the county boundary to Bundoran.

Thirty-two of the ringforts were cashels and 15% were bivallate sites. Ringfort builders avoided land below 30 metres preferring land between 30 and 60 metres. Soil quality was statistically proven to be a key determinant of settlement density. Brown earth and grey-brown podzolic soils were particularly favoured explaining the concentration of sites west of Donegal Bay. The brown earth soils and the podzolic soils of St John's peninsula also attracted a high proportion of sites. The distribution of ecclesiastical sites corresponds broadly with that of ringforts.

Function

Theories accounting for the function of hillforts range from their use as defensive sites to ceremonial enclosures. The Grianán of Aileach could possibly have served both of these purposes and served even more functions.

A number of writers in the nineteenth century suggested that one of the two sites marked as Regia (or royal place) on Ptolemy's map of Ireland, may be identified with the Grianán. The site itself is ancient. Some early texts refer to Aileach as metaphorically being the oldest building in Ireland.

Perhaps the best way to discover the function of this hillfort is to break down its name. The site of the Grianán of Aileach has been known by many names over its long history: Aileach; Aileach Neid; Aileach Frigrinn, Aileach Imchell; Grianán Ailigh and Aileach of the Kings. The word Aileach has a long history and is found both in Ireland and Scotland. Both Petrie and Lacy suggest that it comes from an adjective derived from old Irish "Ail", which means a rock, stone or boulder. Lacy conduces that Aileach, therefore, means either stony or stone place. Petrie goes further by saying it means stone house or habitation. In the same vein, Lacy suggests the etymology of the word might derive from "Ali Theach" meaning stone house. However, Lacy's primary translation seems more plausible due to the name Aileach originally coming from Aileach Mór which is mentioned in the chronology section. The name may have come from the rocky nature of the area or possibly acts as a description of the stone cashel itself.

The word Grianán means sunny place. It was appropriated by the early Irish to mean a place with a view. This is probably the sense in which the word was used to describe the Grianán under discussion. An earlier theory was that the word meant "temple of the sun". This theory has not been substantiated. There is much evidence that the word was constantly used in a figurative sense to signify a distinguished residence or palace. Perhaps, if interpreted in this sense it may mean that if one is in the presence of a king, one will always be in a sunny place. The best summary one can contrive from the etymological breakdown of the name is that it means "The Stone Palace of the Sunny View".

In the historic period, from the middle of the sixth century, the Grianán of Aileach is always thought of as the capital of the northern Ui Neill, the dynasty descended from Niall of the Nine Hostages. It acted as such up until the twelfth century. However, as it was destroyed in 1050, it was the capital in name only. It was the site where the Kings of Aileach held their inauguration ceremonies. It is written in the Tripartite Life of St. Patrick that Patrick blessed the fortress and left a symbolic flagstone there prophesying that many kings and clerics would come from the place. This flagstone can no longer be found at the fortress. It is believed that a preserved flagstone at Belmont House School in Derry, called St Columb's Stone, is the inauguration stone. On one side of the stone, which is 2 metres square, are carved two feet marks. However, there is no substantiating evidence to back this up.

Grianán of Aileach was the secular centre of northwest Donegal while the ecclesiastical settlement at Derry was the religious centre. Together, they acted as the political hub of the region. Aileach's political and strategic importance was such that the annals report that it was attacked at least three times during its existence. In 674, Fínsnechta Fledach, King of Ireland, destroyed the fort. Perhaps, this was the earlier hillfort that stood on the site before the cashel was built. In 937, during the reign of Muirchertach mac Néill, Viking raiders demolished the site. Vikings had settled at Lough Swilly and Lough Foyle during this period.

In 1006, Brian Boru, marched through the territory of the Cenel Conail and the Cenel Eogain and probably came to Aileach. In 1101, another king of Munster, Muirchertach Ua Briain, came to Inishowen where he proceeded to plunder and ravage the region. He destroyed the Grianán of Aileach in revenge for the destruction and demolition of Kincora by Domnall Ua Lochlainn in 1088.

While the main function of this particular hillfort was that of a royal capital, ringforts in general in Ireland functioned as a native version of the common European settlement pattern known as einzelhöfe: dispersed individual farmsteads. However, hillforts are of communal rather than single-family importance. It is possible that some ringforts functioned throughout their existence only as cattle enclosures, or with no domestic function. It is unlikely that Aileach was used in such a fashion during or after it ceased to function as a royal fort. The entrance is too low and narrow for cattle to move through. This narrowness of the entrance may be for defensive purposes.

The only building foundation in the fort, besides the walls, was that of the penal church. Bernard mentions no other foundations. He does mention the finding of some fluted columns which may indicate that there was a stone structure within the fort walls. There is no evidence for any house-like structures though. Circular houses, which are directly associated with the main phase of ringfort occupation, tended to be located towards the centre of the enclosure placing them furthest from an outside attack. If such a house stood in the fort, any trace of it would have been destroyed while the church was being built.

In mythology

In Irish mythology and folklore, the ringfort is said to have been originally built by the Dagda, a god and the celebrated king of the Tuatha Dé Danann, who planned and fought the battle of the second or northern Magh Tuireadh, against the Fomorians. The fort was erected around the grave of his son Aedh who had been killed through jealousy by Corrgenn, a Connacht chieftain. The history of the death of Aedh, and the building of Aileach, is given at length in a poem preserved in the Book of Lecan which has been printed with an English translation (verse 38 Ordnance Memoir of the parish of Templemore, Dr Perie). The verses regarding the building of this rath follow:

"Then were brought the two good men

In art experts,

"Garbhan and Imcheall", to Eochaid [Daghda],

The fair-haired, vindictive;

he ordered these a rath to build, Aileach."

Around the gentle youth:

That it should be a rath of splendid sections—

The finest in Erinn.

Neid, son of Indai, said to them,

[He] of the severe mind,

That the best hosts in the world could not erect

A building like Aileach.

Garbhan the active proceeded to dress

And to cut [the stones];

Imcheall proceeded to set them

All around in the house.

The building of Aileach's fastness came to an end,

Though it was a laborious process;

The top of the house of the groaning hostages

"One stone closed".

In a subsequent verse of this poem (verse 54), the author says that Aileach is the senior or father of all the buildings in Erinn. It also states that in later times it was called Aileach Frigrind. According to another poem written by Flann of Monasterboice and preserved in the Book of Leinster, Frigrind was a famous builder who claimed the protection of the monarch Fiacha Sraibhthine who was slain in the battle of Dubh Chomar, in Meath, a.d. 322;[4] the monarch gave him the ancient fort of Aileach for his dwelling-place. Here Frigrind built a splendid house of wood for his wife from red yew, carved and emblazoned with gold and bronze; thick set it with shining gems.[4] It appears clearly from this very ancient poem that not only was the outer Rath, or protective circle, of Aileach built of stone by the two masons Imcheall and Garbhan, but the palace and other houses within the enclosure were also built of stone (nay, even of chipped and cut stone). According to the chronology of the Annals of the Four Masters, Aileach was built seventeen hundred years before the Christian era. Also worth noticing is the fact that Aileach is one of the few spots in Ireland that is marked in its proper place by the geographer Ptolemy of Alexandria, who some say lived in the second century, nearly two hundred years before the time of Frigrind. Ptolemy distinguishes the Rath as a royal residence.[4]

Site today

The town of Burt is the nearest community and the fortress stands mainly intact insofar as its main walls and features are concerned. Portions of the fortress were destroyed over time but much was rebuilt in the nineteenth century with a view towards retaining the historic nature and aesthetics of the fortress. Dr. Walter Bernard is recorded as having directed the restoration work. The site is now owned by the Irish government.

More restoration work has taken place since 2001 by the Office of Public Works due to a wall collapse and is the subject of public controversy. If any dimensional change in the building's architecture has occurred, nothing about it has been published yet. There are some visible signs of its restoration. Large sections of the wall have been replaced. These sections are easily visually differentiated from the original wall by their shape and colour. Some of the upper parts of the wall have been cemented, probably to prevent falling stones. An iron gate has been set into the entrance. In 2007, the entrance corridor was supported by iron girders which have since been removed.

In popular culture

The filmmaker Gerard Lough used the fort as a location for his 2015 film Night People by filming a sequence there over the course of a two-day period at Blue hour.[5]

Armand Gatti filmed a scene at the fort in his 1983 film Nous étions tous des noms d'arbres ("And our names were names of trees").[6]

The fort appears in video games such as Total War: Thrones of Britannia and the Wrath of the Druids DLC expansion for Assassin's Creed Valhalla.

Bibliography

- Bernard, Walter (1879), "Exploration and Restoration of the Ruin of the Grianan of Aileach", Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy, 2nd, 1. Polite Literature and Antiquities: 415–23

- pp.415-23 ; Plate XVI ; Plate XVII, via haithitrust.org

- Colby, T. (1837), "County of Londonderry", Ordnance Survey of Ireland, vol. 1

- "Grianan of Aileach Fort Restoration", Archaeo Forums, 7 May 2007, archived from the original on 21 May 2011

- Lacy, Brian (1983), The Archaeological Survey of County Donegal, Lifford

- Lacy, Brian (1984), "The Grianán of Aileach", Donegal Annual: 5–24

- Lacy, Brian (2001), "The Grianán of Aileach - A Note on its Identification", Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, 131: 145–149, JSTOR 25549872

- Raftery, Barry (1972), Thomas, Charles (ed.), "Irish Hillforts" (PDF), The Iron Age in the Irish Sea Province

- Stout, Matthew (1997), The Irish Ringfort

- Moore, Fionnbarr (2010), Heritage Guide No. 48: The Grianán of Aileach, Co. Donegal-National Monument No. 140

References

- ↑ "National Monuments of County Donegal in State Care" (PDF). heritageireland.ie. National Monument Service. p. 1. Retrieved 14 August 2022.

- ↑ Bartlett, Thomas. A Military History of Ireland. p.37

- 1 2 Moore 2010.

- 1 2 3 Manners and Customs of the Ancient Irish, p 10., O Curry E.

- ↑ "Grianán of Aileach". www.irishstones.org. Archived from the original on 14 April 2018. Retrieved 14 April 2018.

- ↑ "Nous étions tous des noms d'arbres (1983)". IMDb. Archived from the original on 26 September 2021. Retrieved 21 July 2018.