Metaphysical terms in René Guénon's works contains the definition of some metaphysical terms used in René Guénon's writings.

In his metaphysical writings, René Guénon has stated precise definitions concerning key terms in metaphysics. This article summarizes some of them. Guénon's writings make use of words and terms, of fundamental signification, which receive a precise definition throughout his books. These terms and words, although receiving a usual meaning and being used in many branches of human sciences, have, according to René Guénon, lost substantially their original signification (e.g. words such as "metaphysics", "initiation", "mysticism", "personality", "form", "matter").[1] This article provides the definition given by René Guénon to some of the words used extensively in his works.

Definitions

| Term and/or idea | Definition and/or remarks |

| Metaphysics |

Introduction to the Study of the Hindu doctrines, part II, « The general characteristics of eastern thought », chapter V: « Essential characters of metaphysics », p. 70. |

| Identity of the knowing and being |

Introduction to the study of the Hindu doctrines, p. 155. |

| Initiation and mysticism |

Perspectives on initiation, chapter 1: « The initiatic and mystical paths », p. 8. |

| Initiation |

Perspectives on initiation, chapter 8: « Initiatic transmission », p. 48. |

| The Self |

Man and His Becoming According to the Vedanta, chapter 2: « Fundamental distinction between the 'Self' and the 'ego' », p. 23. |

| Paramâtmâ, individuality, personality |

Man and His Becoming According to the Vedanta, chapter 2: « Fundamental distinction between the 'Self' and the 'ego' », p. 24. |

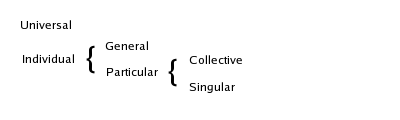

| Universal and individual |

Man and His Becoming According to the Vedanta, chapter 2: « Fundamental distinction between the 'Self' and the 'ego' », pp. 26-27. |

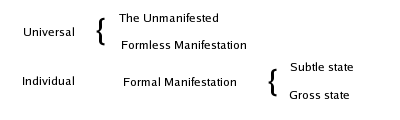

| Manifestation and non-manifestation |

Man and His Becoming According to the Vedanta, chapter 2: « Fundamental distinction between the 'Self' and the 'ego' », p. 27.

|

| The human state of being |

Man and His Becoming According to the Vedanta, chapter 2: « Fundamental distinction between the 'Self' and the 'ego' », p. 28. |

| Samâdhi and ecstasy |

Studies in Hinduism, chapter 3: « Kundalinî Yoga », note 3, pp. 17-18. |

| Form, matter, essence and substance |

The Reign of Quantity and the Signs of Times, chapter 1: « Quality and Quantity », p. 12. |

| The Retroactive Refutation |

حوليات البلاغة التقليدية (English: Annals of Traditionalist Argumentation); vol. III, p. 642.

|

| Matter and the principle of individuation |

The Reign of Quantity and the Signs of Times, chapter 6: « The Principle of Individuation », p. 47. |

Notes and references

- ↑ c.f. for instance The Eastern Metaphysics and Introduction to the Study of the Hindu doctrines w.r.t. the meaning of the word "metaphysics", the first chapter of The Reign of Quantity and the Signs of the Times on the meanings of the words "form" and "matter", the chapter "Kundalini-Yoga" in his Studies on Hinduism about the translation of Sanskrit word samâdhi as "ecstasy", Man and his Becoming according to Vedânta" on the word "personality", Theosophism: History of a Pseudo-Religion" on the word "theosophy" etc.

- ↑ Guenon, René (1927). The Crisis of the Modern World. Sophia Perennis; Revised Edition (1 January 2001). pp. 39–54. ISBN 9780900588242.,

- ↑ Bollack, J. (1990). "La cosmologie parménidéenne de Parménide," in R. Brague and J.-F. Courtine (eds.), Herméneutique et ontologie: Mélanges en hommage à Pierre Aubenque. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France. pp. 17–53.