The Haiti indemnity controversy involves an 1825 agreement between Haiti and France that included France demanding an indemnity of 150 million francs to be paid by Haiti in claims over property – including Haitian slaves – that was lost through the Haitian Revolution in return for diplomatic recognition, with the debt removing $21 billion from the Haitian economy.[1][2] The first annual payment alone was six times Haiti's annual revenue.[1] The payment was later reduced to 90 million francs in 1838, equivalent to $32,535,940,803 in 2022, with Haiti paying about 112 million francs in total.[3] Over the 122 years between 1825 and 1947, the debt severely hampered Haitian economic development as payments of interest and downpayments totaled a significant share of Haitian GDP, constraining the use of domestic financial funds for infrastructure and public services.[1][4]

France's demand of payments in exchange for recognizing Haiti's independence was delivered to the country by several French warships in 1825, twenty-one years after Haiti's declaration of independence in 1804.[5][6] Due to the unrealistic demands pushed by France, Haiti was forced to take large loans from French bank Crédit Industriel et Commercial, enriching the bank's shareholders.[7] Though France received its last indemnity payment in 1888,[1] the government of the United States funded the acquisition of Haiti's treasury in 1911 in order to receive interest payments related to the indemnity.[8] In 1922, the rest of Haiti's debt to France was moved to be paid to American investors.[9] It took until 1947 – about 122 years – for Haiti to finally pay off all the associated interest to the National City Bank of New York (now Citibank).[8][10] In 2016, the Parliament of France repealed the 1825 ordinance of Charles X, though no reparations have been offered by France.[2] These debts have been denounced by some historians and activists as the root of modern Haiti's poverty and a case of odious debt, although others point to the lack of growth relative to the neighbouring Dominican Republic, even since the debt was repaid, as evidence for other factors. In 2022, The New York Times published a dedicated investigative series on the topic.[11]

History

Saint-Domingue colony

Saint-Domingue, now Haiti, was the richest and most productive European colony in the world going into the 1800s.[12][13] France acquired much of its wealth by using slaves, with the slave population of Saint-Domingue accounting for seven percents (800,000 out of 12,000,000) of the entire Atlantic slave trade.[14] Between the years of 1697 and 1804, French colonists brought 800,000 West African slaves to what was then known as Saint-Domingue to work on the vast plantations.[14] The Saint-Domingue population reached 520,000 in 1790, and of those 425,000 were slaves.[14] The mortality rate among slaves was high, with the French often working slaves to death and transporting more to the colony instead of providing necessities as it was cheaper.[13] At the time, goods from Haiti comprised thirty percent of French colonial trade while its sugar represented forty percent of the Atlantic market.[13] About sixty percent of the coffee consumed in European markets was also produced in the colony.[14]

Independent Haiti

.jpg.webp)

Haiti's legacy of debt began shortly after a widespread slave revolt against the French, with Haitians gaining their independence from France in 1804, followed by a genocide against much of the remaining European population of Haiti.[15] Jean-Jacques Dessalines, Governor-General of Haiti, ordered the execution of remaining whites; in response, Thomas Jefferson, United States President, feared a slave revolt would spread to the United States, ceased the aid that was initiated by his predecessor John Adams and sought the international isolation of Haiti.[16][17] Haiti had hoped that the United Kingdom would support their recognition due to the kingdom's strained history with France, even providing British merchants lower import duties, though during the Congress of Vienna in 1815 the British government agreed not to prevent France's actions by "whatever means possible, including that of arms, to recover Saint-Domingue and to subdue the inhabitants of that colony".[13][18] In 1823, the United Kingdom recognized the independence of Colombia, Mexico and other nations in the Americas while refraining from extending recognition to Haiti, further disillusioning Haitians seeking recognition.[18]

Until France recognized Haiti's independence, the fear of reconquest and continued isolation would persist among Haitians.[18] Haiti was also financially strained after purchasing equipment to defend itself from invasion.[18] Knowing that improvements could not happen until Haiti received international recognition, President of Haiti Jean-Pierre Boyer sent envoys to negotiate terms with France.[18] At one meeting in Brussels on 16 August 1823, Haiti proposed waiving all import duties for five years on French products and then duties would be halved at the end of the period; France refused the offer outright.[18] By 1824, President Boyer began to prepare Haiti for a defensive war, moving armaments inland to provide increased protection.[18] After being summoned by France, two Haitian envoys travelled to Paris.[18] At the meetings held between June and August 1824, Haiti offered to pay indemnity to France, though negotiations ended after France said it would only recognize their former territory on the west half of Hispaniola and that it sought to maintain control of Haiti's foreign relations.[18]

Ordinance of Charles X

As a show of force, captain Ange René Armand, baron de Mackau, in the ship La Circe, along with two men-of-war, arrived at Port-au-Prince on 3 July 1825.[13][18] Soon after, more warships led by admirals Pierre Roch Jurien de La Gravière and Grivel arrived at Haiti.[18] A total of fourteen French warships equipped with 528 cannons presented demands that Haiti compensate France for its loss of slaves and the 1804 Haiti massacre.[13][18][3]

The following ordinance of Charles X, King of France, was presented:[18]

| "Charles, by the grace of God, King of France and Navarre.

"To everyone here present, Greetings. "Having seen articles 14[19] and 73[20] of the Charter "Wishing to attend to the interest of French Commerce, to the misfortunes of the former colonists of Saint-Domingue and to the precarious condition of the present inhabitants of the island; "We have ordered and order the following: "Art. I. The ports of the French part of Saint-Domingue shall be open to the commerce of all nations. "The duties levied in these ports either on ships or merchandise at the times of their entry or departure shall be equal and uniform for all nations except for the French flag, on behalf of which these duties are to be reduced to half the amount. "Art. II. The present inhabitants of the French part of Saint-Domingue shall pay at the Caisse des Dépots et Consignations of France , in five annual instalments, the first one due on 31 December 1825, the sum of one hundred and fifty millions of francs, in order to compensate the former colonists who may claim an indemnity. "Art. III. Under these conditions we grant, by the present Ordinance, to the present inhabitants of the French part of Saint-Domingue the full independence of their Government. "And the present Ordinance shall be sealed with the great seal. "Done at Paris in the Palace of Tuileries, this 17th of April A. D. 1825, and the first of our reign. "Charles.

"By the King: The Peer of France, Minister-Secretary of State for the Navy and the colonies.

"Comte de Chabrol." |

The Haitians wanted the French to recognize the Spanish part of the island as part of Haitian territory. However, the French flatly ignored this request. France returned the Spanish part of the island to Spain in the Treaty of Paris of 1814, which annulled the Treaty of Basel of 1795.

Under Charles X's ordinance, France demanded an indemnity payment of 150 million francs in exchange for recognizing Haiti's independence.[3] In addition to the payment, Charles ordered that Haiti provide a fifty percent discount on French import duties, making payment to France more difficult.[17] On 11 July 1825, the senate of Haiti signed the agreement of paying indemnity to France.[18]

Border aspect of the Ordinance

Territorial discussions between France and Haiti in the Ordinance

The final discussions between France and Haiti regarding the signing of the Ordinance took place between the months of April and July 1825. By those dates, the Haitians had already been occupying the Spanish part of the Island militarily for 3 years and 1 month.

During the discussions, the Haitians demanded from France that the Spanish part of the island be recognized by France as the territory of Haiti in the aforementioned Ordinance. The French rejected this Haitian demand as inadmissible, ill-founded and lacking legal basis; France returned the Spanish part of the island to Spain in the Treaty of Paris of 1814, which annulled the Treaty of Basel of 1795. Therefore, this territory was not theirs to dispose of, therefore, the Haitians were occupying Spanish territory, not french.

Furthermore, the French were not going to reward Haiti by giving the Haitians territory that did not belong to France, when the Haitians made France lose its most profitable colony in the first place.

The Haitians alleged that they were militarily occupying the territory of an independent state, free of any power, and that the president and founder of that state had recognized the Haitian occupation. The French rejected this claim of the Haitians, since the republic that was founded in the Spanish part of the island was just an attempt at a state that existed only for two months and a few days, and that never received official diplomatic recognition, nor of its metropolis, nor of the international community.

Furthermore, France and the international community had not yet recognized Haiti as an independent nation, therefore, the colony of one empire could not recognize the sovereignty of another colony of another empire.

At the same time, the Haitians wanted France to force the inhabitants of the Spanish part to pay the Haitian Independence Debt, and to also collect local taxes from them, so that they would contribute to the payment of this debt. The French rejected this claim by the Haitians. France did not have to collect compensation from the inhabitants of the Spanish part since they had not created any loss for France that had to be compensated. ̟ Furthermore, the French never created slave plantations on the Spanish part of the island during the time it was under French control.

Indemnity payment

The payments were designed by France to be so large that it would effectively create a "double debt"; France would receive a direct annual payment and Haiti would pay French bankers interest on the loans required to meet France's annual demands.[1] France viewed Haiti's debt as the "principal interest in Haiti, the question that dominated everything else for us", according to a French minister.[1] Much of the debt would be paid directly to the French state-owned Caisse des dépôts et consignations.[2] France ordered Haiti to pay the 150 million francs over a period of five years, with the first annual payment of 30 million francs being six times larger than Haiti's yearly revenue, requiring Haiti to take out a loan from the French bank Ternaux Gandolphe et Cie to make the payment.[1][21] The first 30 million francs required a 24 million franc loan from Ternaux Gandolphe et Cie that resulted in high interest and Haiti's treasury was completely emptied, with a French ship transporting locked shipments of money to Paris.[1][18][21] The story of the first payment – 24,000,000 gold francs – being transported across Paris, from the vaults of Ternaux Gandolphe et Cie to the coffers of the French Treasury was recorded in detail.

Haiti would continue to acquire loans from France and the United States in order to fulfill payments.[13] Such large payments became impossible for Haiti and defaults occurred immediately, with Haiti's late payments often raising tensions with France.[1][18] Ternaux Gandolphe et Cie seized assets of the Haitian government for failing to pay on its loan, though the Tribunal de la Seine overturned these actions on 2 May 1828.[21] On 12 February 1838, France finally agreed to reduce the debt to 90 million francs to be paid over a period of 30 years to compensate former plantation owners who had lost their property; the 2004 equivalent of US$21 billion.[18][3][17][22] President Boyer, who agreed to make the payments, was forced from Haiti in 1843 by citizens who demanded lower taxes and more rights.[1]

By the late-1800s, eighty percent of Haiti's wealth was being used to pay foreign debt; France was the highest collector, followed by Germany and the United States.[13] Henri Durrieu, head of the French bank Crédit Industriel et Commercial (CIC), was inspired to increase revenue for the bank by following the example of state-run banks acquiring capital from other distant French colonies such as Martinique and Senegal.[13] In 1874 and 1875 Haiti took out two large loans from CIC, greatly increasing the nation's debt.[1][7] French banks charged Haiti 40% of the loaned funds just for commissions and other fees and CIC would go on to acquire "much of Haiti's financial future", according to The New York Times.[13] Thomas Piketty described the loans as an early example of "neocolonialism through debt".[7]

From 1880 to 1881, Haiti granted a currency issuance concession to create the National Bank of Haiti (BNH), headquartered in Paris by CIC which was simultaneously funding the construction of the Eiffel Tower.[4][13][7] BNH was described as an entity of "pure extraction" by Paris School of Economics economic historian Éric Monnet.[7] On the board of the BNH was Édouard Delessert, the great-grandson of French slave trader and owner Jean-Joseph de Laborde who established himself when France controlled Haiti.[7] Haitian Charles Laforestrie, who mainly lived in France and successfully pushed for Haiti to accept the 1875 loan with the CIC, later retired from his positions in Haiti amid corruption allegations, joining the BNH board in Paris after its founding.[7] CIC would go on to take $136 million in 2022 US dollars from Haiti and distribute those funds among shareholders, who made 15% annual returns on average, not returning any of the earnings to Haiti.[7] These funds distributed among shareholders would ultimately cost Haiti at least $1.7 billion of development.[7] Under the French-controlled BNH, Haitian funds were overseen by France and all transitions resulted with a commission fee, with CIC shareholders profits often being larger than the entire budget for Haiti's public works.[1][7] The French government finally acknowledged the payment of 90 million francs in 1888 and over a period of about seventy years, Haiti paid 112 million francs to France, about $560 million in 2022.[1]

United States occupation of Haiti

In 1903, Haitian authorities began to accuse the BNH of fraud and by 1908, Haitian Minister of Finance Frédéric Marcelin pushed for the BNH to work on the behalf of Haitians, though French officials began to devise plans to reorganize their financial interests.[7] French envoy to Haiti Pierre Carteron wrote following Marcelin's objections that "It is of the highest importance that we study how to set up a new French credit establishment in Port-au-Prince ... Without any close link to the Haitian government."[7] Businesses from the United States had pursued the control of Haiti for years and from 1910 to 1911, the United States Department of State backed a consortium of American investors – headed by the National City Bank of New York – to acquire control of the National Bank of Haiti to create the Bank of the Republic of Haiti (BNRH), with the new bank often holding payments from the Haitian government, leading to unrest.[1][7][8][23]

France would still keep a stake in the BNRH, though CIC was excluded.[7] Following the overthrow of Haitian president Michel Oreste in 1914, the National City Bank and the BNRH demanded the United States Marines to take custody of Haiti's gold reserve of about US$500,000 – equivalent to $13,526,578 in 2021 – in December 1914; the gold was transported aboard the USS Machias (PG-5) in wooden boxes and place into the National City Bank's New York City vault days later.[1][23][24][25] The overthrow of Haiti's president Vilbrun Guillaume Sam and subsequent unrest resulted in President of the United States Woodrow Wilson ordering the invasion of Haiti to protect American business interests on 28 July 1915.[26] Six weeks later, the United States seized control of Haiti's customs houses, administrative institutions, banks and the national treasury, with the United States using a total of forty percent of Haiti's national income to repay debts to American and French banks for the next nineteen years until 1934.[27] In 1922, BNRH was completely acquired by National City Bank, its headquarters was moved to New York City and Haiti's debt to France was moved to be paid to American investors.[28][9] Under U.S. government control, a total of forty percent of Haiti's national income was designated to repay debts to American and French banks.[27] Haiti would pay its final indemnity remittance to National City Bank in 1947, with the United Nations reporting that at that time, Haitians were "often close to the starvation level".[1][13]

Aftermath

According to The New York Times, the payments cost Haiti much of its development potential, removing about $21 to $115 billion of growth from Haiti (about one to eight times the nation's total economy) over two centuries, according to calculations conducted by fifteen prominent economists. Haiti could potentially have experienced a level of development on par with neighboring Caribbean island nations that gained independence in the early 19th century, such as the Dominican Republic and Jamaica.[1][2]

The history of Haiti's indemnity is not taught as part of education in France.[2] Aristocratic French families have also forgotten that their families profited from the debt payments of Haiti.[2] President of France François Hollande would eventually describe the money paid by Haiti to France as "the ransom of independence" and in 2016, the Parliament of France repealed the 1825 ordinance in a symbolic gesture.[2]

Reparation requests

Aristide government

In 2003, President of Haiti Jean-Bertrand Aristide demanded that France pay Haiti over 21 billion U.S. dollars, what he said was the equivalent in today's money of the 90 million gold francs Haiti was forced to pay Paris after winning its freedom from France.[29][30] French and Haitian officials later claimed to The New York Times that Aristide's calls for reparations led to French and Haitian officials collaborating with the United States on removing Aristide because France feared that discussions of reparations would set a precedent for other former colonies, such as Algeria.[2]

In February 2004, a coup d'état occurred against President Aristide. The United Nations Security Council, of which France is a permanent member, rejected a 26 February 2004, appeal from the Caribbean Community (CARICOM) for international peacekeeping forces to be sent into its member state Haiti. However, the Security Council voted unanimously to send troops into Haiti three days later, just hours after Aristide's controversial resignation. The provisional prime minister Gerard Latortue who assumed office after the coup would later rescind the reparations demand, calling it "foolish" and "illegal".

Myrtha Desulme, chairperson of the Haiti-Jamaica Exchange Committee, told IPS, "I believe that [the call for reparations] could have something to do with it, because they [France] were definitely not happy about it, and made some very hostile comments ... I believe that he did have grounds for that demand, because that is what started the downfall of Haiti."[29][30][31]

In the 19 years following the coup d'etat, all of Haiti's government received substantial support from France and the United States, and none of them made a claim for restitution of the independence debt.

2010 earthquake

Following the 2010 Haiti earthquake, the French foreign ministry made a formal request to the Paris Club on 17 January 2010 to completely cancel Haiti's external debt.[32] A number of commentators, for example The New York Times’ Matt Apuzzo, Selam Gebrekidan, Constant Méheut, and Catherine Porter, analyze how Haiti’s current troubles stem from its colonial past [33] drawing references from the early 19th-century indemnity demand and how it had severely depleted the Haitian government's treasury and economic capabilities.

Gallery

Copies of the ordinance

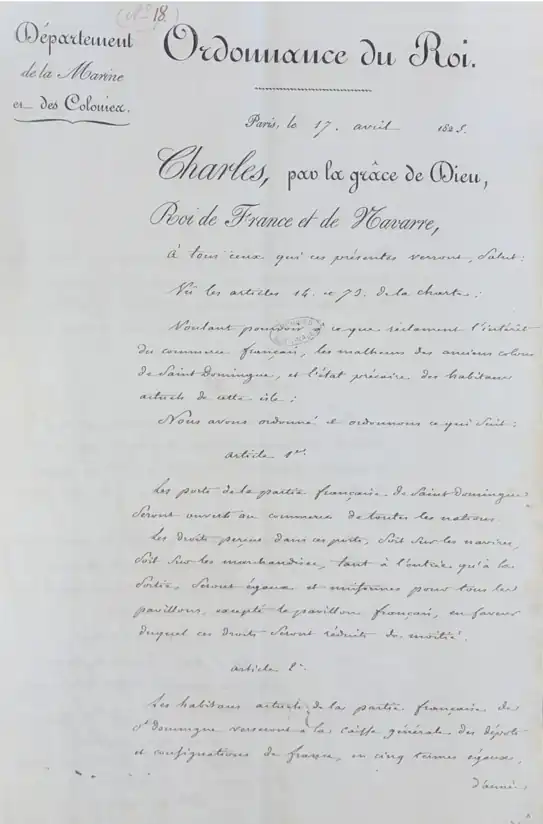

Image of the first page of the original handwritten ordinance

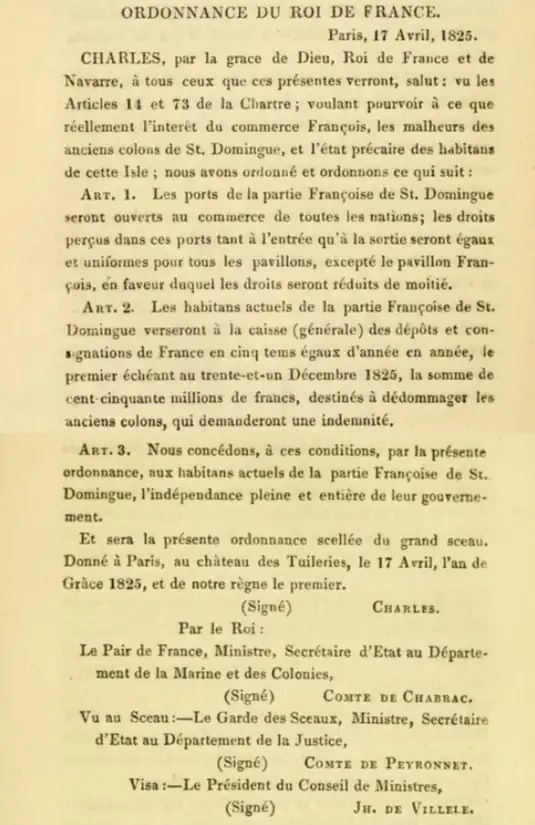

Image of the first page of the original handwritten ordinance Printed copy of the ordinance.

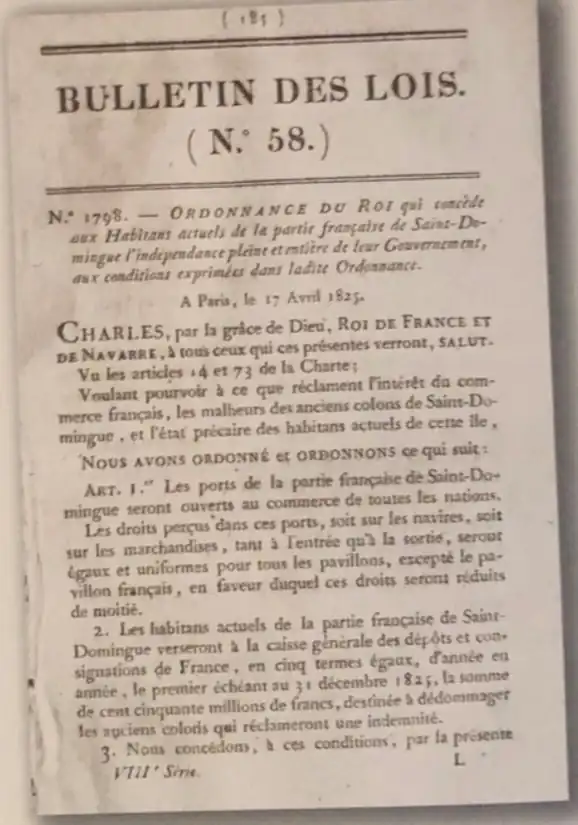

Printed copy of the ordinance. Photograph of the ordinance in the French Law Bulletin, the official gazette of the French government (Law Bulletin, Volume No. 58 – Law No. 1798 – April 17, 1825)

Photograph of the ordinance in the French Law Bulletin, the official gazette of the French government (Law Bulletin, Volume No. 58 – Law No. 1798 – April 17, 1825)

Other images

Engraving showing Haitian President Jean Pierre Boyer with an inkwell, quill, and scroll in his right hand, ready to sign the ordinance. To the left of him, in the background, French sailors can be seen on the Port-au-Prince dock, making sure that the ordinance is signed.

Engraving showing Haitian President Jean Pierre Boyer with an inkwell, quill, and scroll in his right hand, ready to sign the ordinance. To the left of him, in the background, French sailors can be seen on the Port-au-Prince dock, making sure that the ordinance is signed. Engraving titledː

Engraving titledː

"His Majesty, Charles X, The Beloved, recognizing

the Independence of Saint-Domingue

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Gamio, Lazaro; Méheut, Constant; Porter, Catherine; Gebrekidan, Selam; McCann, Allison; Apuzzo, Matt (2022-05-20). "Haiti's Lost Billions". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2022-05-24.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Méheut, Constant; Porter, Catherine; Gebrekidan, Selam; Apuzzo, Matt (2022-05-20). "Demanding Reparations, and Ending Up in Exile". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2022-05-24.

- 1 2 3 4 de Cordoba, Jose (2004-01-02). "Impoverished Haiti Pins Hopes for Future On a Very Old Debt". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved 2021-02-20.

- 1 2 Porter, Catherine; Méheut, Constant; Apuzzo, Matt; Gebrekidan, Selam (2022-05-20). "The Root of Haiti's Misery: Reparations to Enslavers". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2022-05-23.

- ↑ "France Urged to Pay $40 Billion to Haiti in Reparations for "Independence Debt"". Democracy Now!. 17 August 2010.

- ↑ "Why The US Owes Haiti Billions - The Briefest History". www.africaspeaks.com.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Apuzzo, Matt; Méheut, Constant; Gebrekidan, Selam; Porter, Catherine (2022-05-20). "How a French Bank Captured Haiti". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2022-05-24.

- 1 2 3 Douglas, Paul H. from Occupied Haiti, ed. Emily Greene Balch (New York, 1972), 15–52 reprinted in: Money Doctors, Foreign Debts, and Economic Reforms in Latin America. Wilmington, Delaware: Edited by Paul W. Drake, 1994.

- 1 2 Hubert, Giles A. (January 1947). "War and the Trade Orientation of Haiti". Southern Economic Journal. 13 (3): 276–284. doi:10.2307/1053341. JSTOR 1053341.

- ↑ Marquand, Robert (2010-08-17). "France dismisses petition for it to pay $17 billion in Haiti reparations". Christian Science Monitor. ISSN 0882-7729. Retrieved 2019-08-31.

- ↑ Porter, Catherine; Méheut, Constant; Apuzzo, Matt; Gebrekidan, Selam (2022-05-20). "The Root of Haiti's Misery: Reparations to Enslavers". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2022-05-27.

- ↑ McLellan, James May (2010). Colonialism and Science: Saint Domingue and the Old Regime (reprint ed.). University of Chicago Press. p. 63. ISBN 978-0226514673. Retrieved 2010-11-22.

[...] French Saint Domingue at its height in the 1780s had become the single richest and most productive colony in the world.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Alcenat, Westenly. "The Case for Haitian Reparations". Jacobin. Retrieved 2021-02-20.

- 1 2 3 4 "Latest News | The Canada-Haiti Information Project". canada-haiti.ca.

- ↑ Orizio, Riccardo (2001). Lost White Tribes: The End of Privilege and the Last Colonials in Sri Lanka, Jamaica, Brazil, Haiti, Namibia, and Guadeloupe. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0-7432-1197-0.

- ↑ "Milestones: 1784–1800 - Office of the Historian". United States Department of State. Retrieved 2021-02-20.

- 1 2 3 Barnes, Joslyn (2010-01-19). "Haiti: The Pearl of the Antilles". The Nation. ISSN 0027-8378. Retrieved 2021-02-20.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Leger, J.N. Haiti: Her History and Her Detractors. The Neale Publishing Co.: New York & Washington. 1907. Accessed 19 February 2011.

- ↑ The King is the Supreme Head of the State, commands the land and sea forces, declares war, makes treaties of peace, alliance and commerce, appoints to all places of public administration, and makes the necessary regulations and ordinances for the execution of the laws and the security of the state.

- ↑ The colonies will be governed by special laws and regulations

- 1 2 3 Piot, Gaston (1887). De l'alienation de l'ager publicus pendant la période républicaine: Des règles de compètence applicables aux états et aux souverains étrangers (in French). Impr. F. Levé. p. 83.

- ↑ Sommers, Jeffrey. Race, Reality, and Realpolitik: U.S.-Haiti Relations in the Lead Up to the 1915 Occupation. 2015. ISBN 1498509142. p. 124.

- 1 2 Gebrekidan, Selam; Apuzzo, Matt; Porter, Catherine; Méheut, Constant (2022-05-20). "Invade Haiti, Wall Street Urged. The U.S. Obliged". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2022-05-24.

- ↑ "U.S. Invasion and Occupation of Haiti, 1915-34". United States Department of State. 2007-07-13. Retrieved 2021-02-24.

- ↑ Bytheway, Simon James; Metzler, Mark (2016). Central Banks and Gold: How Tokyo, London, and New York Shaped the Modern World. Cornell University Press. p. 43. ISBN 978-1501706509.

- ↑ Weinstein, Segal 1984, p. 28.

- 1 2 Weinstein, Segal 1984, p. 29.

- ↑ Munro, Dana G. (1969). "The American Withdrawal from Haiti, 1929–1934". The Hispanic American Historical Review. 49 (1): 1–26. doi:10.2307/2511314. JSTOR 2511314.

- 1 2 Jackson Miller, Dionne (March 12, 2004). "Haiti: Aristide's Call for Reparations From France Unlikely to Die". Inter Press Service news. Archived from the original on 2 December 2008. Retrieved 20 April 2009.

- 1 2 Frank E. Smitha. "Haiti, 1789 to 1806". Archived from the original on 2009-02-12. Retrieved 2009-04-20.

- ↑ "A Country Study: Haiti – Boyer: Expansion and Decline". * Library of Congress. 200a. Archived from the original on 2009-06-01. Retrieved 2007-08-30.

- ↑ "France asks Paris Club to speed up Haiti debt". Reuters. 2010-01-15. Retrieved 2022-12-05.

- ↑ "Haiti's Troubled Path to Development". Council on Foreign Relations. Retrieved 2022-12-05.