| Halszkaraptorines Temporal range: Late Cretaceous, | |

|---|---|

| |

| Holotype specimen of Halszkaraptor escuilliei | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | Theropoda |

| Family: | †Dromaeosauridae |

| Subfamily: | †Halszkaraptorinae Cau et al., 2017 |

| Type genus | |

| †Halszkaraptor escuilliei Cau et al., 2017 | |

| Genera | |

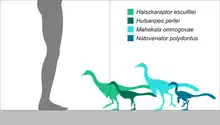

Halszkaraptorinae is a basal ("primitive") subfamily of Dromaeosauridae (or possibly Unenlagiidae) that includes the enigmatic genera Halszkaraptor, Natovenator, Mahakala, and Hulsanpes. Halszkaraptorines are definitively known only from Late Cretaceous strata in Asia, specifically in Mongolia. Following the recent discovery of Natovenator, a member of the subfamily, the group is believed to have a semiaquatic lifestyle.

History of discovery

The first known remains of halszkaraptorines were found in sandstone sediments in 1970 during a Polish-Mongolian expedition at the Barun Goyot Formation, Gobi Desert. Later in 1982, they were described by Polish palaeontologist Halszka Osmólska and used as the holotype for the new genus and species Hulsanpes perlei, honoring the Mongolian paleontologist Altangerel Perle. Although the affinities of these fossils were not fully understood, they were tentatively interpreted as belonging to Deinonychosauria.[1] In 1992 dromaeosaurid-like fossils were recovered from the Tugriken Shire locality of the Djadokhta Formation and described as a new species in 2007 by Alan H Turner and team. This new taxon, Mahakala omnogovae, was regarded as a primitive dromaeosaurid mainly based on its body proportions.[2] In 2015 the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences received a small theropod fossil specimen, hailing from England and Japanese private collections. The specimen, through negotiations between the former institute, Eldonia and Mongolian authorities, was lastly returned to the Institute of Paleontology and Geology, Mongolian Academy of Sciences. According to associated documents of the specimen, it was illegally poached from the Djadokhta Formation (Ukhaa Tolgod locality; however, sediments may suggest that, alternatively, it was recovered from nearby Bayn Dzak locality) during an unknown year, eventually falling into private collections. The specimen was in 2017 formally described by Andrea Cau with colleagues, naming the genus and species Halszkaraptor escuilliei, in honor of Halszka Osmólska and François Escuillié, paleontologist that made negotiations for returning the poached specimen to Mongolia possible. With the naming of Halszkaraptor, the subfamily Halszkaraptorinae was also coined to contain this taxon and relatives, namely Hulsanpes and Mahakala.[3]

Description

Halszkaraptorines were relatively small theropods, reaching lengths similar to those of modern-day ducks.[2][3] They are diagnosed by their long necks, proximal caudal vertebrae with oriented articular processes (projections of the vertebra fits with an adjacent vertebra) and prominent zygapophyseal laminae (plates of bone that form the posterior walls of each vertebra), a flattened ulna with a sharp posterior margin, ilium with a shelf-like supratrochanteric (above the trochanter of the femur) process, metacarpal III shaft transversely as thick as that of metacarpal II, a posterodistal surface on the femoral shaft with an elongate fossa bound by a lateral crest and the proximal half of metatarsal III being unconstricted and markedly convex anteriorly.[3]

Classification

Halszkaraptorinae is defined as the most inclusive clade that contains Halszkaraptor escuilliei but not Dromaeosaurus albertensis, Unenlagia comahuensis, Saurornithoides mongoliensis or Vultur gryphus.[3] The cladogram below is based on the phylogenetic analysis conducted in 2022 by Lee et al. in their description of Natovenator.[4]

| Dromaeosauridae |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Paleobiology

In 2017 a comparison of the fossils of Halszkaraptor with the bones of extant crocodilians and aquatic birds revealed evidence of a semiaquatic lifestyle. Cau and colleagues suggested that halszkaraptorines were obligate bipeds on land, but also swimmers that used its forelimbs to push through water and used their long necks for foraging. Such traits allowed them to exploit both terrestrial and aquatic paleoecosystems.[3]

References

- ↑ Osmólska, H. (1982). "Hulsanpes perlei n.g. n.sp. (Deinonychosauria, Saurischia, Dinosauria) from the Upper Cretaceous Barun Goyot Formation of Mongolia". Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie, Monatshefte. 1982 (7): 440–448.

- 1 2 Turner, A.H.; Pol, D.; Clarke, J.A.; Erickson, G.M.; Norell, M.A. (2007). "A Basal Dromaeosaurid and Size Evolution Preceding Avian Flight". Science. 317 (5843): 1378–1381. Bibcode:2007Sci...317.1378T. doi:10.1126/science.1144066. PMID 17823350.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Cau, A.; Beyrand, V.; Voeten, D. F. A. E.; Fernandez, V.; Tafforeau, P.; Stein, K.; Barsbold, R.; Tsogtbaatar, K.; Currie, P. J.; Godefroit, P. (2017). "Synchrotron scanning reveals amphibious ecomorphology in a new clade of bird-like dinosaurs". Nature. 552 (7685): 395–399. Bibcode:2017Natur.552..395C. doi:10.1038/nature24679. PMID 29211712. Supplementary Information

- ↑ Lee, S.; Lee, Y.-N.; Currie, P. J.; Sissons, R.; Park, J.-Y.; Kim, S.-H.; Barsbold, R.; Tsogtbaatar, K. (2022). "A non-avian dinosaur with a streamlined body exhibits potential adaptations for swimming". Communications Biology. 5 (1185). doi:10.1038/s42003-022-04119-9. ISSN 2399-3642.

.png.webp)

.jpg.webp)