Hamdanid Dynasty الحمدانيون al-Hamdaniyyun | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 890–1004 | |||||||||||

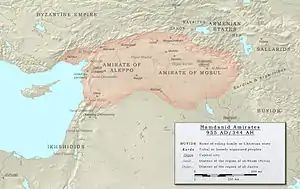

Hamdanid territory in 955 during the rule of Sayf al-Dawla | |||||||||||

| Capital | Mardin (892–895) Mosul (905–990) (in Iraq) Aleppo (944–1002) (in Syria) | ||||||||||

| Common languages | |||||||||||

| Religion | Shia Islam | ||||||||||

| Government | Hereditary monarchy | ||||||||||

| Emir | |||||||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages | ||||||||||

• Established | 890 | ||||||||||

• Husayn ibn Hamdan establishes himself as leader of Al-Jazira for the Abbasids. | 895 | ||||||||||

• Sayf al-Dawla establishes himself in Aleppo after successfully countering the Ikhshidids of Egypt. | 944 | ||||||||||

• Disestablished | 1004 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Historical Arab states and dynasties |

|---|

.jpg.webp) |

The Hamdanid dynasty (Arabic: الحمدانيون, romanized: al-Ḥamdāniyyūn) was a Shia Muslim Arab[1][2] dynasty of Northern Mesopotamia and Syria (890–1004). They descended from the ancient Banu Taghlib tribe of Mesopotamia and Arabia.

History

The Hamdanid dynasty was founded by Hamdan ibn Hamdun. By 892–893, he was in possession of Mardin, after fighting the Kharijites of the Jazira.[3] In 895, Caliph al-Mutadid invaded and Hamdan fled Mardin.[3]

Hamdan's son, Husayn, who was at Ardumusht, joined the caliph's forces.[3] Hamdan later surrendered to the caliph and was imprisoned.[3] In December 908, Husayn conspired to establish Ibn al-Mu'tazz as Caliph. Having failed, Husayn fled until he asked for mediation through his brother Ibrahim. Upon his return, he was made governor of Diyar Rabi'a.[3] In 916, Husayn, due to a disagreement with vizier Ali b. Isa, revolted, was captured, imprisoned, and executed in 918.[3]

Hamdan's other son, Abdallah, was made governor of Mosul in 905–906.[4] He conducted campaigns against the Kurds in that region and in 913–914, was dismissed from his post and subsequently revolted.[3] Abdallah submitted himself to Mu'nis, and with his pardon was made governor of Mosul in 914–915.[3] During his brother Husayn's revolt, both he and his brother Ibrahim were temporarily imprisoned.[3] By 919, Abdallah was commanding an army against Yusuf b. Abi l'Sadj, governor of Adharbaydjan and Armenia.[3] During their rule the Hamdanids intermarried with Kurdish dignitaries.[5]

The rule of Hassan Nasir al-Dawla (929–968), governor of Mosul and Diyar Bakr, was sufficiently tyrannical to cause him to be deposed by his own family.

His lineage still ruled in Mosul, a heavy defeat by the Buyids in 979 notwithstanding, until 990. After this, their area of control in northern Iraq was divided between the Uqaylids and the Marwanids.

Ali Sayf al-Dawla 'Sword of the State' ruled (945–967) northern Syria from Aleppo, and became the most important opponent of the Christian Byzantine Empire's re-expansion. His court was a centre of culture, thanks to its nurturing of Arabic literature, but it lost this status after the Byzantine conquest of Aleppo.

To stop the Byzantine advance, Aleppo was put under the suzerainty of the Fatimids in Egypt, but in 1003 the Fatimids deposed the Hamdanids.

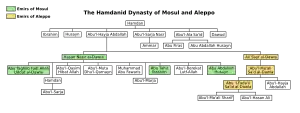

Hamdanid rulers

Hamdanids in Al-Jazira

- Hamdan ibn Hamdun

- al-Husayn ibn Hamdan (895–916)

- Abdallah ibn Hamdan (906–929)

- Nasir al-Dawla (929–967)

- Abu Taghlib (967–978)

- Directly administered as part of the Buyid-controlled Abbasid Caliphate, 979–981

- Abu Tahir Ibrahim ibn Nasir al-Dawla (989–990)

- Abu Abdallah al-Husayn ibn Nasir al-Dawla (989–990)

- Deposed by the Uqaylid chieftain Muhammad ibn al-Musayyab

Hamdanids in Aleppo

- Sayf al-Dawla (945–967)

- Sa'd al-Dawla (967–991)

- Sa'id al-Dawla (991–1002)

- Deposed by the ghulam Lu'lu' al-Kabir

See also

References

- ↑ Corbin 2014, p. 158.

- ↑ Bosworth 1996, p. 85.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Canard 1971, p. 126.

- ↑ Bosworth 1996, p. 86.

- ↑ Kennedy 2004, p. 269.

Sources

- Bosworth, C.E. (1996). The New Islamic Dynasties. Columbia University Press.

The Hamdanids came from the Arab tribe of Taghlib..[..]...the Hamdanids tended to follow the Shī'ī inclinations...

- Canard, Marius (1971). "Ḥamdānids". In Lewis, B.; Ménage, V. L.; Pellat, Ch. & Schacht, J. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam. Volume III: H–Iram (2nd ed.). Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 126–131. OCLC 495469525.

- Corbin, Henry (2014). History Of Islamic Philosophy. Routledge.

Further reading

- Bikhazi, Ramzi J. (1981). The Hamdanid Dynasty of Mesopotamia and North Syria 254–404/868–1014. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan.

- Canard, Marius (1951). Histoire de la dynastie des Hamdanides de Jazîra et de Syrie (in French). Algiers: Faculté des Lettres d'Alger. OCLC 715397763.

- Freytag, G. W. (1856). "Geschichte der Dynastien der Hamdaniden in Mosul und Aleppo". Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft (in German). X: 432–498.

- Freytag, G. W. (1857). "Geschichte der Dynastien der Hamdaniden in Mosul und Aleppo". Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft (in German). XI: 177–252.

- Kennedy, Hugh N. (2004). The Prophet and the Age of the Caliphates: The Islamic Near East from the 6th to the 11th Century (2nd ed.). Harlow, England: Longman. ISBN 978-0-58-240525-7.

- Hukam (Arabic)