The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill is a coeducational public research university located in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, United States. It is one of three schools to claim the title of the oldest public university in the United States. The first public institution of higher education in North Carolina, the school opened on February 12, 1795.

Until the 1970s, the university was simply known as the University of North Carolina. After the other state universities were combined into a single public university system, called the University of North Carolina, the original institution was given the new name of University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Beginnings: Late 18th century

.jpg.webp)

After the first constitution of the state of North Carolina was adopted in 1776 after the United States declared its independence from the Kingdom of Great Britain, work began to establish the independent state of North Carolina. Article 41 of North Carolina Constitution set forth to establish affordable schools and universities for the instruction of the young people in the state. Samuel Eusebius McCorkle made the first attempt to implement article 41. (He is remembered in the name McCorkle Place, on the UNC-CH campus.) In November 1784 he introduced a bill in the North Carolina General Assembly to establish a state university. The bill was rejected due to financial restraints and political turmoil.[1]

Five years later, chartered by the North Carolina General Assembly on December 11, 1789, and beginning instruction in 1795, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (then named simply the University of North Carolina) became the oldest public university in the nation, as measured by start of instruction as a public institution. The university was the first land grant school in North Carolina; however, shortly after they were stripped of their title for using funds in an improper manner. The College of William & Mary, chartered in 1693, and the University of Georgia, chartered in 1785, are both older as measured by date of charter. However, William & Mary was originally a private institution, and did not become a public university until 1906. Georgia has always been a public institution, but did not start classes until 1801.[2][3] A political leader in revolutionary America, William Richardson Davie, led efforts to build legislative and financial support for the university.[4]

The site of New Hope Chapel was chosen for "the purity of the water, the salubrity of the air and the great healthfulness of the climate", as well as its location at the center of the state, at the intersection of two major roads.[5]: 7 [6]

The university opened in a single building, which came to be called Old East. Still in use as a residence hall, it is the oldest building originally constructed for a public university in the United States.[7] Davie, in full Masonic Ceremony[8] as he was the Grand Master of the Grand Lodge of North Carolina at the time,[9] laid the cornerstone on October 12, 1793, near an abandoned Anglican chapel which led to the naming of the town as Chapel Hill.[6][10] The first student, Hinton James, from near Burgaw in what is now Pender County, arrived on February 12, 1795. While a student, James was among the students who broke off from the Debating Society (later renamed the Dialectic Society) to form the Concord Society (later renamed the Philanthropic Society). A dormitory on the UNC campus is named in his honor. It is currently the southernmost on-campus dormitory and houses primarily first-year students.[11]

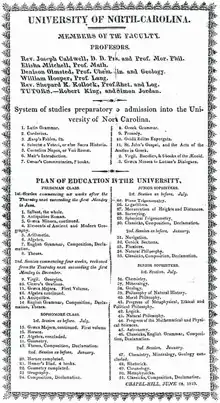

When the university opened there were 41 students, rising to 100 in the second term, with a faculty of five.[5]: 7 Entering students, according to an 1819 publication, were expected to be able to read the Bible in Greek, and to have read Caesar's Commentarii de Bello Gallico (7 books), Virgil's Bucolics and Æneid, and Ovid in Latin, the latter in an "editio expurgata".[12]

When it opened the university received no state financial support, as the charter made no provision for it. The school depended on donations of money and land, "but North Carolinians did not give these generously, feeling that the university was too expensive, too difficult to reach from all areas of the state, and that its liberal and skeptical teachings were insufficiently Christian".[5]: 7

Slavery and the birth of the university

"Members of the Board of Trustees were among the largest slave owners in the state."[13]: 17–18

In the summer of 1793, ...slaves began clearing land to build the first public university in the new nation. Black workers labored through the summer heat to clear a main street for the village of Chapel Hill and to construct the foundations of Old East, the first building at the University of North Carolina.[13]: 22–23

At a Southern university, "slaves made the bricks that went into buildings, they worked the grounds and buildings around the campus. They carried water, serviced the dormitories, worked in the dining halls."[14]

Growth and development: Early 19th century

The early 19th century saw a period of much growth and development with the help of the backing of the trustees. Through this growth, the university began to move away from its original purpose, to train leadership for the state, as it added to the curriculum, first starting with the typical classical trend. By 1815, the university started giving equal ground to the natural sciences, and in 1818 the Department of Chemistry was founded. This development continued with the establishment in 1831 of the first astronomical observatory at a state university in the United States.

Considerable information about university life in Chapel Hill in the antebellum period is provided by George Moses Horton, "the black bard of Chapel Hill" and the first North Carolinian to publish a book of literature. He delivered produce to the campus every week, and goaded by the students, he found he could speak in public and write poems; composing them at night, by memory since he could not write, he provided acrostics and similar light verse. The students, "the sons of wealthy planters",[5]: 6 paid him 25¢ to 75¢ for these pieces, which they wrote out and sent to their girlfriends.

According to Horton, the students "seemed more interested in sports, gambling, and pleasures of the table than in their studies. They often engaged in boisterous riots and at various times destroyed laboratories, recitation rooms, and blackboards. They attacked faculty with clubs, stones, and pistols; sang ribald songs; violently rang the university bell; stole farmers' produce and animals; and perpetrated assorted vulgar and dangerous pranks."[5]: 6 On the university's own posted history, we find that students hoisted pigs into dormitory rooms. "Cheating became a sport for many students, who transformed it into 'a trial of wit between the class and the Professor, and it was considered good fun to win.' They cut holes in classroom floors, put good students under them, and passed questions down by a string—what was called "working the telegraph."[15] "By all accounts, university students, faculty, and servants drank steadily and heavily.... Even on the Sabbath."[5]: 7

Student behavior later reached the attention of the Trustees, who deplored "gross irregularities of conduct by students on the railroad cars, at circuses and other places". The students on one railroad car were "so boisterous" that it was unhitched, since it was the last car, and the train proceeded without them.[16]: 666 A thrown "fireball" deliberately started a fire that destroyed the university's bell and belfry.[16]: 653

The first issue of a North Carolina University Magazine, literary in focus, was published by senior students in 1844. Describing the earlier venture as having been "starved out", No. 1 of a second North Carolina University Magazine appeared in February, 1852.

The Hedrick affair

During the lead-up to the 1856 United States presidential election, an attack was made in the press on an unidentified professor who allegedly supported anti-slavery candidate John C. Frémont, whose election, the Raleigh Standard opined, would inevitably lead to "a separation of the states". "Let our schools and seminaries of learning be scrutlnized; and if black Republicans [Frémont supporters] be found in them, let them be driven out. That man is neither a fit nor a safe instructor of our young men, who even inclines to Fremont and black Republicanism."[17]

Following up on this, a lengthy letter to the editor soon appeared; signed only "Alumnus" (a student), the author was identified by university historian Kemp Battle as Joseph A. Engelhard.[16]: 654

[C]an the Trustees of our own State University invite pupils to the institution under their charge with the assurance that this main stream of education contains no deadly poison at its fountain head? ...[W]e have been reliably informed that a professor at our State University is an open and avowed supporter of Fremont, and declares his willingness—nay, his desire—to support the black Republican ticket. ...Is he a fit or safe instructor for our young men? ...[O]ught he not to be "required to leave," at least dismissed from a situation where his poisonous influence is so powerful, and his teachings so antagonist to the "honor and safety" of the University and the State? ....We rnust have certain security, under existing relations of North with South, that at State Universities at least we will have no canker-worm preying at the very vitals of Southern institutions.[18]

In another lengthy letter, published by the author as a pamphlet after it appeared in the Standard,[19] Professor Benjamin Hedrick, an honors graduate of the university, said that there was "little doubt" that he was the professor attacked. He quoted Thomas Jefferson as saying that "Nothing is more certainly written in the book of fate, than that these people are to be free". Citing as his "political teachers", besides Jefferson, fellow Southerners George Washington, Patrick Henry, James Madison, Edmund Randolph, Henry Clay, as well as Benjamin Franklin and Daniel Webster, "I cannot believe that slavery is preferable to freedom, or that slavery extension is one of the constitutional rights of the South."[20] According to the newspaper when presenting his letter, "We take it for granted that Prof. Hedrick will be promptly removed."[21] He was hung in effigy; faculty disowned him; parents threatened to withdraw their sons; and alumni joined the public in calling for his dismissal.[5]: 19 He refused to resign and since "Mr. Hedrick had greatly, if not entirely, destroyed his power to be of further benefit to the University", he was terminated within a week, though his salary was paid through the end of the term.[16]: 655 The only faculty member to defend him, French instructor Henry Harrisse,[16]: 655 was terminated at the same time.[16]: 657–659 [22] Hounded by a mob, Hedrick left his native state.[5]: 19 [23][24]

Civil War

During the Civil War, the university was among the few in the Confederacy that managed to keep its doors open. Students from other seceding states left, as did many North Carolina students; by 1864, there were only 47 students. "The war ruined the University financially, so that by 1866, faculty salaries could not be paid; the University was $100,000 in debt; its buildings had deteriorated, and its entire endowment, [converted into Confederate money,] was lost through the insolvency of the Bank of North Carolina."[5]: 29 Because of lack of students and funding, the university was forced to close from 1870 until 1875.

Later 19th century

After North Carolina's readmission to the Union in 1868, new political leaders came to power. They attempted to change the direction of the university through political appointments, but these were blocked. The university restored its prestige through growth and innovation, continuing to develop scientific programs. For example, it undertook a massive program to support farmers by conducting scientific analyses of fertilizers and their effectiveness in relation to different crops and soil types in North Carolina. It opened a normal school in 1877, which was both the first university summer school and the first normal school linked to a university in the United States. The university reopened its law school in 1877 and established schools of medicine in 1879 and of pharmacy in 1880.[25]

Consolidation: Early 20th century

In 1915, the mission of the university was broadened to include research and public service,[26] culminating in the Association of American Universities admitting UNC as a member in 1922. This change lead to a large number of new professional schools in the coming years, including:

- School of Education (1915)

- School of Commerce, now Kenan-Flagler Business School (1919)

- School of Public Welfare, now the School of Social Work (1920)

- School of Library Science, now the School of Information and Library Science (1931)

- Institute of Government, now the School of Government (1931)

- School of Public Health, now the Gillings School of Global Public Health (1936)

- Division of Health Affairs (1949)

- School of Dentistry (1949)

- School of Journalism, now the School of Media and Journalism (1950)

- School of Nursing (1950)

In 1915, Cora Zeta Corpening became the first woman enrolled into the medical school.[27]

In 1932, UNC became one of the three original campuses of the consolidated University of North Carolina (since 1972 called the University of North Carolina system). During the process of consolidation, programs were moved among the schools, which prevented competition. For instance, the engineering school moved from UNC to North Carolina State University in Raleigh in 1938.[28]

In 1963, the consolidated university was made fully coeducational. As a result, the Woman's College of the University of North Carolina was renamed the University of North Carolina at Greensboro.

Until the second half of the 20th century, only white students were admitted.

Silent Sam incident

On August 20, 2018, student protestors tore down the university's Confederate monument, known as Silent Sam. The pedestal (plinth) and plaques were removed shortly afterwards on instructions from then-Chancellor Carol Folt (who announced her resignation in the same letter[29]). Although there has been much discussion about what to do with the monument, as of December 2020 it remains in storage.

Renaming Carr Hall

In July 2020, the university's Carr Hall, which was named for former pro-white supremacy, KKK-supporting Confederate veteran Julian Shakespeare Carr, was renamed "Student Affairs Building."[30] Carr had previously served on the university's Board of Trustees.[31]

2023 shooting

On August 28, 2023, during the second week of the fall semester, a shooting occurred on the campus that resulted in the death of one faculty member.[32]

References

- ↑ Lindemann, Erika (n.d.). "1795-1819: The Establishment of the University". Documenting the American South. Archived from the original on June 27, 2018. Retrieved December 1, 2018.

- ↑ "Davie and the University's Founding — Silhouette of the Campus of the University of North Carolina, ca. 1820". The Carolina Story — A Virtual Museum of University History. UNC University Library. Archived from the original on 2007-03-11. Retrieved 2008-04-05.

- ↑ "C. Dixon Spangler Jr. named Overseers president for 2003-04". Archives. Harvard University Gazette. Archived from the original on 2003-06-21. Retrieved 2008-04-05.

- ↑ "William R. Davie's Bill to Establish the University of North Carolina, November 12, 1789". Documenting the American South. UNC University Library. Archived from the original on 2008-05-12. Retrieved 2008-04-05.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Sherman, Joan R (1997). Black Bard of North Carolina : George Moses Horton and His Poetry. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0807823414.

- 1 2 "Virtual Museum of University History, UNC Chapel Hill–Davie laying the cornerstone of East Building, 12 October 1793, reproduced from the 1935 edition of The Yackety Yack.". Archived from the original on 2007-06-12. Retrieved 2008-04-05.

- ↑ "Old East Tour Stop". Virtual Tour. Archived from the original on 2002-02-20. Retrieved 2008-04-05.

- ↑ Wheeler, John H. (1851). Historical sketches of North Carolina from 1584 to 1851. Compiled from original records, official documents and traditional statements ; with biographical sketches of her distinguished statesmen, jurists, lawyers, soldiers, divines, etc (Google e-Book). Vol. 1 (1st ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott, Grambo, & Co. p. 117. Archived from the original on 2020-01-11. Retrieved 2011-08-16.

- ↑ "Officers of the Grand Lodge, A.F. & A.M. of North Carolina, the first 100 years". Raleigh, North Carolina, USA: Grand Lodge of North Carolina. Archived from the original on 2010-12-15. Retrieved 2011-08-16.

- ↑ "Virtual Museum of University History, UNC Chapel Hill-Old East, ca. 1797. Pen and ink sketch by John Pettigrew". Archived from the original on 2007-06-12. Retrieved 2008-04-05.

- ↑ "Virtual Museum of University History, UNC Chapel Hill-David Ker (1758-1805)". Archived from the original on 2007-06-12. Retrieved 2008-04-05.

- ↑ University of North Carolina (June 28, 1819), System of studies preparatory [t]o admission into the University of Nor[th] Carolina (PDF), archived (PDF) from the original on December 16, 2015, retrieved October 18, 2020

- 1 2 Chapman, John K. (Yonni) (2006). Black freedom and the University of North Carolina, 1793-1960. Ph.D. dissertation, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Archived from the original on 2020-10-18. Retrieved 2020-10-18.

- ↑ Brophy, Alfred L. (2008), "The University and the Slaves: Apology and its Meaning" (PDF), in Gibney, Mark; Howard-Hassmann, Rhoda E.; Coicaud, Jean-Marc; Steiner, Niklaus (eds.), The Age of Apology: Facing Up to the Past, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, pp. 109–119, at p. 110, archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-03-30, retrieved 2022-08-15

- ↑ University Archives & Records Management Services, University of North Carolina (2006). "Student Misbehavior". The Carolina Story: A Virtual Museum of University History. Archived from the original on October 22, 2020. Retrieved October 15, 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Battle, Kemp P. (1907). History of the University of North Carolina. Volume I: From its Beginning to the Death of President Swain, 1789-1868. Raleigh, North Carolina. Archived from the original on 2020-05-21. Retrieved 2020-08-16.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ "Fremont in the South". Weekly Standard (Raleigh, North Carolina). 17 September 1856. p. 1. Archived from the original on 15 August 2022. Retrieved 16 August 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Alumnus" (Joseph A. Englehard) (1 October 1856). "Fremont in the South". Weekly Standard (Raleigh, North Carolina). p. 4. Archived from the original on 10 July 2021. Retrieved 16 August 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- ↑ Are North Carolinians Freemen?. The pamphlet defending Hedrick contains neither date nor publisher, but it was obviously published by Hedrick in 1856. In addition to the letter of Hedrick and preliminary remarks, it concludes with an abolitionist speech at the University of North Carolina by Judge William Gaston. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: Benjamin Hedrick. 1856. Archived from the original on 2021-07-10. Retrieved 2020-09-07.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ↑ Hedrick, B.S. (4 October 1856). "Professor Hedrick's defence". Semi-Weekly Standard (Raleigh, North Carolina). p. 2. Archived from the original on 10 July 2021. Retrieved 16 August 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Prof. Hedrick, of the University". Semi-Weekly Standard (Raleigh, North Carolina). 4 October 1856. p. 3. Archived from the original on 10 July 2021. Retrieved 16 August 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- ↑ Horton, George Moses (October 2017). Senchyne, Jonathan (ed.). "Individual Influence". PMLA. 132 (5): 1244–1250, at p. 1245. doi:10.1632/pmla.2017.132.5.1244. S2CID 165982360.

- ↑ Benjamin Sherwood Hedrick. The James Sprunt Historical Publications, published under the direction of The North Carolina Historical Society. University of North Carolina. 1910. Archived from the original on 2008-07-24. Retrieved 2020-09-07.

- ↑ Hedrick, Benjamin Sherwood (1856). Are North Carolinians Freemen?. Archived from the original on 2021-07-10. Retrieved 2020-09-07.

- ↑ Battle, Kemp P. (1912). History of the University of North Carolina. Volume II: From 1868 to 1912. Raleigh, North Carolina. Archived from the original on 2021-02-28. Retrieved 2020-08-16.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ "UNC: History and Traditions". University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Archived from the original on 2020-04-27. Retrieved 2019-10-28.

- ↑ Virtual Museum of University History, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. "Cora Zeta Corpening, center, front row, 1916". The Carolina Story: A virtual museum of university history. Archived from the original on 2019-10-28. Retrieved 2020-07-28.

- ↑ Diane Lea; Ruth Little (2006). The Town and Gown Architecture of Chapel Hill, North Carolina, 1795-1975 (Distributed for the Preservation Society of Chapel Hill). Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-3072-0.

- ↑ Folt, Carol (January 14, 2019). "Chancellor Folt announces resignation, orders Confederate Monument pedestal to be removed intact". University Communications, University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill. Archived from the original on November 7, 2020. Retrieved December 11, 2020.

- ↑ Murphy, Kate (July 29, 2020). "These UNC dorms and academic buildings are no longer named after white supremacists". News & Observer. Archived from the original on October 22, 2020. Retrieved October 21, 2020.

- ↑ Green, Hilary N. "Transcription: Julian Carr's Speech at the Dedication of Silent Sam". people.ua.edu. University of Alabama. Archived from the original on March 14, 2020. Retrieved October 21, 2020.

- ↑ Sayers, Devon M.; Levenson, Eric (August 28, 2023). "University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill faculty member is killed in campus shooting, and a suspect is in custody, school says". CNN. Retrieved August 28, 2023.

Further reading

- Battle, Kemp P. (1907). History of the University of North Carolina. Volume I: From its Beginning to the Death of President Swain, 1789-1868. Raleigh, North Carolina.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Battle, Kemp P. (1912). History of the University of North Carolina. Volume II: From 1868 to 1912. Raleigh, North Carolina.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Manuscripts Department, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (2005). "Slavery and the Making of the University". Retrieved October 11, 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)