| History of the United Kingdom |

|---|

|

|

|

The history of the monarchy of the United Kingdom and its evolution into a constitutional and ceremonial monarchy is a major theme in the historical development of the British constitution.[1] The British monarchy traces its origins to the petty kingdoms of Anglo-Saxon England and early medieval Scotland, which consolidated into the kingdoms of England and Scotland by the 10th century. Anglo-Saxon England had an elective monarchy, but this was replaced by primogeniture after England was conquered by the Normans in 1066. The Norman and Plantagenet dynasties expanded their authority throughout the British Isles, creating the Lordship of Ireland in 1177 and conquering Wales in 1283. In 1215, King John agreed to limit his own powers over his subjects according to the terms of Magna Carta. To gain the consent of the political community, English kings began summoning Parliaments to approve taxation and to enact statutes. Gradually, Parliament's authority expanded at the expense of royal power.

From 1603, the English and Scottish kingdoms were ruled by a single sovereign in the Union of the Crowns. From 1649 to 1660, the tradition of monarchy was broken by the republican Commonwealth of England, which followed the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. Following the installation of William and Mary as co-monarchs in the Glorious Revolution, a constitutional monarchy was established with power shifting to Parliament. The Bill of Rights 1689, and its Scottish counterpart the Claim of Right Act 1689, further curtailed the power of the monarchy and excluded Roman Catholics from succession to the throne.

In 1707, the kingdoms of England and Scotland were merged to create the Kingdom of Great Britain, and in 1801, the Kingdom of Ireland joined to create the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. The British monarch was the nominal head of the vast British Empire, which covered a quarter of the world's land area at its greatest extent in 1921.

The Balfour Declaration of 1926 recognised the evolution of the Dominions of the Empire into separate, self-governing countries within a Commonwealth of Nations. In the years after the Second World War, the vast majority of British colonies and territories became independent, effectively bringing the Empire to an end. George VI and his successors, Elizabeth II and Charles III, adopted the title Head of the Commonwealth as a symbol of the free association of its independent member states. The United Kingdom and fourteen other independent sovereign states that share the same person as their monarch are called Commonwealth realms. Although the monarch is shared, each country is sovereign and independent of the others, and the monarch has a different, specific, and official national title and style for each realm.

English monarchy

Anglo-Saxon period (800s–1066)

The origins of the English monarchy lie in the Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain in the 5th and 6th centuries. In the 7th century, the Anglo-Saxons consolidated into seven kingdoms known as the Heptarchy. At certain times, one king was strong enough to claim the title bretwalda (Old English for "over-king").[2]

After 865, Viking invaders conquered all the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms except for Wessex, which survived due to the leadership of Alfred the Great (r. 871–899). Alfred absorbed Kent and western Mercia and was the first to style himself "king of the Anglo-Saxons".[3][4] His son Edward the Elder (r. 899–924) continued to recover and consolidate control over the other Anglo-Saxon kingdoms. Only the Kingdom of York and Northumbria remained in Viking hands at his death. Alfred's grandsons Æthelstan (r. 924–939), Edmund I (r. 939–946), and Eadred (r. 946–955) completed the reconquest of these holdouts. Alfred's dynasty could now claim to rule a single Kingdom of England.[5]

In theory, all governing authority resided with the king. He alone could make Anglo-Saxon law, mint coins, levy taxes, raise the fyrd, or make foreign policy. In reality, kings needed the support of the English church and the nobility to rule.[6] The king governed in consultation with the Witan, the council of bishops, ealdormen, and thegns he chose to advise him.[7] The Witan also elected new kings from among male royal family members (æthelings). Primogeniture was not the definitive rule governing succession, so strong candidates replaced weak ones.[8]

A monarch's rule was not legitimate unless he received coronation by the church. Coronation consecrated a king, giving him priest-like qualities and divine protection. The coronation of Edgar the Peaceful (r. 959–975) served as a model for future British coronations. The service started with the king's acclamation by his people. He then swore a threefold oath to protect the church, defend his people, and administer justice. The oath imposed moral obligations on monarchs consistent with good Christian kingship, and unhappy subjects often cited the oath when demanding better government. The service concluded with the anointing and crowning.[9][10]

While the capital was at Winchester, the king traveled with his itinerant court from one royal vill to another as they collected food rent and heard petitions. The king's income came from revenue from the royal demesne (now known as the Crown Estate), judicial fines, and taxation of trade. The geld (land tax) was also an essential source of revenue.[11] At the local level, England was divided into shires and hundreds. Shire courts and hundred courts were presided over by royal officials: the ealdorman for a shire and a reeve for a hundred.[12]

House of Wessex

.jpg.webp)

Alfred the Great's grandson Æthelstan (r. 924–939) first used the title "king of the English" and is considered the founder of the English monarchy.[14] He died childless, and his younger half-brother Edmund I (r. 939–946) succeeded him. After Edmund's murder, his two young sons were passed over in favor of their uncle, Eadred (r. 946–955). He never married and raised his nephews as his heirs. The eldest, Eadwig (r. 955–959), succeeded his uncle, but his younger brother Edgar (r. 959–975) was soon declared king of Mercia and the Danelaw. Eadwig's death prevented civil war, and Edgar the Peaceful became the undisputed king of all England in 959.[15]

Edward the Martyr (r. 975–978) followed Edgar as king. His younger brother, Æthelred the Unready (r. 978–1016), murdered Edward and became king. The Danes began raiding England in the 990s, and Æthelred resorted to buying them off with ever more expensive payments of Danegeld. Æthelred's marriage to Emma of Normandy deprived the Danes of a place to shelter before crossing the Channel. Still, it did not prevent Swein Forkbeard, king of Denmark, from conquering England in 1013.[16]

After Swein died in 1014, the English invited Æthelred to return from exile if he agreed to address complaints against his earlier rule, including high taxes, extortion, and the enslavement of free men. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records this agreement, which historian David Starkey called "the first constitutional settlement in English history".[17] Æthelred died in 1016, and his son Edmund Ironside became king. Swein's son Cnut invaded England and defeated Edmund at the Battle of Assandun. Afterwards, the two divided England, with Edmund ruling Wessex and Cnut taking the rest.[18]

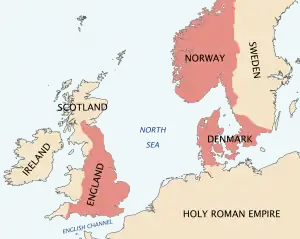

Cnut the Great and his sons

After Ironside's death, Cnut (r. 1016–1035) became king of all England and quickly married Æthelred's widow, Emma of Normandy. Cnut united England with the kingdoms of Denmark and Norway in what historians call the North Sea Empire. Because Cnut was not in England for much of his reign, he divided England into four parts (Wessex, East Anglia, Mercia, and Northumbria). He appointed trusted earls to rule each region. The creation of large earldoms covering multiple shires necessitated the office of sheriff or "shire reeve". The sheriff was the king's direct representative in the shire. He oversaw the shire court and collected taxes and royal estate dues.[19]

Earl Godwin of Wessex was the strongest earl and Cnut's chief minister. When Cnut died in 1035, rival sons contended for the throne: Emma's son Harthacnut (then in Denmark) and Ælfgifu's son Harold Harefoot (in England). Godwin supported Harthacnut, but Leofric, earl of Mercia, backed Harold.[20] In a compromise, Harold became king of Mercia and Northumbria, while Harthacnut became king of Wessex. Harold died in 1040, and Harthacnut ruled a reunited England until he died in 1042.[18]

Some members of the House of Wessex saw Cnut's death as a chance to regain power. Æthelred's youngest son, Alfred Aetheling, returned to England but was captured, blinded, and died of his injuries in 1037.[21]

Edward the Confessor

%252C_f.5_-_BL_Royal_MS_20_A_II.jpg.webp)

Edward the Confessor (r. 1042–1066) was the only surviving son of Æthelred and Emma. In 1041, Harthacnut recalled his half-brother from exile in Normandy. When he died without heirs, the forty-year-old Edward was the natural successor. He had spent most of his life in Normandy and culturally was "probably more French than English".[22]

As king, Edward invited his nephew, Edward the Exile, to return to England. Edward died before reaching England, but his son Edgar Ætheling and daughter Margaret were able to return. Margaret would marry Malcolm III of Scotland.[21]

By this time, the Anglo-Saxon government had become sophisticated.[23] Edward appointed the first chancellor, Regenbald, who kept the king's seal and oversaw the writing of charters and writs. The treasury had developed into a permanent institution by this time as well.[24] London was becoming the political as well as the commercial capital of England. Edward furthered this transition by building Westminster Palace and Westminster Abbey.[25]

Despite his government's sophistication, Edward had much less land and wealth than Earl Godwin and his sons. In 1066, the Godwinson estates were worth £7,000, while the king's estates were worth £5,000.[26] To counter the power of the Godwinsons, Edward created a French party loyal to him. He made his nephew, Ralph of Mantes, the earl of Hereford. He overturned the election of a Godwin relative to be Archbishop of Canterbury and appointed Robert of Jumièges instead. In 1051, Edward's brother-in-law, Count Eustace of Boulogne, visited England and initiated a quarrel with Godwin. Ultimately, Edward had the entire Godwinson family outlawed and forced into exile.[27]

Around this time, Edward invited his relative William, duke of Normandy, to England. According to Norman sources, the king nominated William as his heir. However, Edward's favouritism towards the French was unpopular with the English people. With popular support, Godwin returned to England in 1052. Edward had to restore the Godwinsons to their former lands. This time, Edward's French supporters were outlawed.[28]

In 1066, Edward died childless. The children of Edward the Exile had the best hereditary claim to the throne. However, Harold Godwinson, earl of Wessex, claimed King Edward promised the throne to him. Harold had more support among the English people and was made king by the Witan.[29]

House of Normandy (1066–1154)

William the Conqueror

William, Duke of Normandy, disputed Harold's succession. He claimed that Edward the Confessor promised him the throne. He was also the great-nephew of Emma of Normandy, wife of Æthelred and Cnut. In addition, his wife Matilda of Flanders was a direct descendant of Alfred the Great.[30] In 1066, William invaded England, and Harold was killed at the Battle of Hastings.[31] The English then elected (but never crowned) Edgar the Ætheling, the Confessor's fifteen-year-old great-nephew. After English resistance collapsed, Edgar submitted to William, who was crowned king on Christmas Day 1066 at Westminster Abbey.[32]

It took nearly five years of fighting before the Norman Conquest of England was secure. Across England, the Normans built castles for defence as well as intimidation of the locals. In London, William ordered construction of the White Tower, the central keep of the Tower of London. Once finished, the White Tower "was the most imposing emblem of monarchy that the country had ever seen, dwarfing all other buildings for miles around."[33]

The Normans preserved the basic system of English government. The Witan's role of consultation and advice was continued by the curia regis (Latin for "king's court").[34] The local shire and hundred courts continued to exist as well.[35] There were also important changes. The kings of England were dukes of Normandy and nominal vassals to the kings of France. For the next centuries, the English monarchy would be deeply involved with French politics, and English kings usually spent most of their time in France.[36]

The Conqueror claimed ownership of all land in England.[note 1] The lands of the old Anglo-Saxon nobility were confiscated and distributed to a French-speaking Anglo-Norman aristocracy according to the principles of feudalism.[38][34] The king gave fiefs to his barons who in return owed the king fealty and military service.[39] Nevertheless, Domesday Book records that the king remained the single largest landholder in England.[40] At times, there was tension between the monarch and his Norman vassals, who were used to French models of government in which royal power was much weaker than in England. The 1075 Revolt of the Earls was defeated by the king, but the monarchy continued to resist forces of feudal fragmentation.[41]

The Norman kings designated nearly a third of England as royal forests (i.e. royal hunting preserves).[42] The forest provided kings with food, timber, and money. People paid the king for rights to graze cattle or cut down trees. A system of forest law developed to protect the royal forests. Forest law was unpopular because it was arbitrary and infringed on the property rights of other landholders. A landholder's right to hunt deer or farm his land was limited if it fell within the royal forest.[43]

The church was critical to William's conquest of England. In 1066, it owned between 25 and 33 per cent of all land,[44] and appointment to bishoprics and abbacies were important sources of royal patronage. The Norman invasion received the blessing of Pope Alexander II, who wanted William to oversee church reform and to remove unfit bishops. William forbade ecclesiastical cases (those involving marriage, wills, and legitimacy) from being heard in secular courts; jurisdiction was handed over to church courts. But William also tightened royal control over the church. Bishops were banned from traveling to Rome, and royal permission was needed to enact new canon law or to excommunicate a noble.[45][46]

Henry I

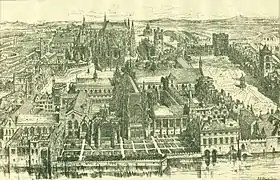

The death of William I in 1087 illustrates the absence of any firm rules of succession. William gave Normandy to his oldest son, Robert Curthose, while his second son, William II or "Rufus" (r. 1087–1100), was given England.[47] Between 1098 and 1099, the Great Hall at Westminster Palace, the king's main residence, was built. It was one of the largest secular buildings in Europe, and a monument to the Anglo-Norman monarchy.[48]

On 2 August 1100, Rufus was killed while hunting in the New Forest. His younger brother, Henry I (r. 1100–1135), was hastily elected king by the barons at Winchester on August 3 and crowned king at Westminster Abbey on August 5, just three days after his brother's death. At the coronation, Henry not only promised to rule well; he renounced the unpopular policies of his brother and promised to restore the laws of Edward the Confessor. This oath was written down and distributed throughout England as the Coronation Charter, which was reissued by all future 12th-century kings and was incorporated into Magna Carta.[49][50]

During Henry's reign, the royal household was formalised. It was divided into the chapel in charge of royal documents (which evolved into the chancery), the chamber in charge of finances, and the master-marshal in charge of travel (the court remained itinerant during this period). The household also included several hundred mounted household troops. The office of justiciar—effectively the king's chief minister—developed out of the need for a viceroy when the king was in Normandy and was mainly concerned with royal finance and justice.[51] Under the first justiciar, Roger of Salisbury, the Exchequer was established to manage royal finances.[52] Royal justice became more accessible with the appointment of local justices in each shire and itinerant justices traveling judicial circuits of multiple shires.[53] Historian Tracy Borman summarised the impact of Henry I's reforms as "transform[ing] medieval government from an itinerant and often poorly organised household into a highly sophisticated administrative kingship based on permanent, static departments."[54]

Henry married Matilda of Scotland, the niece of Edgar the Ætheling. This marriage was widely seen as uniting the House of Normandy with the House of Wessex and produced two children, Matilda (who married Holy Roman Emperor Henry V in 1114) and William Adelin (a Norman-French variant of Ætheling).[55] But in 1120, England was thrown into a succession crisis when William Adelin died in the sinking of the White Ship.[56] In 1126, Henry I made a controversial decision to name his daughter Empress Matilda (his only surviving legitimate child) his heir and forced the nobility to swear oaths of allegiance to her. In 1128, the widowed Matilda married Geoffrey of Anjou, and the couple had three sons in the years 1133–1136.[57]

Stephen

Despite the oaths sworn to her, Matilda was unpopular both for being a woman and because of her marriage ties to Anjou, Normandy's traditional enemy.[58] Following Henry's death in 1135, his nephew, Stephen of Blois (r. 1135–1154), laid claim to the throne and took power with the support of most of the barons. Matilda challenged his reign; as a result, England descended into a period of civil war known as the Anarchy (1138–1153). While Stephen maintained a precarious hold on power, he was ultimately forced to compromise for the sake of peace. Both sides agreed to the Treaty of Wallingford by which Stephen adopted Matilda's son, Henry FitzEmpress, as his son and heir.[59]

Plantagenets (1154–1399)

Henry II

On December 19, 1154, Henry II (r. 1154–1189) became the first king of a new dynasty, the House of Plantagenet. He was also the first king crowned King of England rather than King of the English. Henry founded the Angevin Empire, which controlled almost half of France including Normandy, Anjou, Maine, Touraine, and the Duchy of Aquitaine.[60]

Henry's first task was restoring royal authority in a kingdom fractured by years of civil war. In some parts of the country, nobles were virtually independent of the Crown. In 1155, Henry expelled foreign mercenaries and ordered the demolition of illegal castles. He also dealt quickly and effectively with rebellious lords, such as Hugh de Mortimer.[61]

Henry's legal reforms had a profound impact on English government for generations. In earlier times, English law was largely based on custom. Henry's reign saw the first official legislation since the Conquest in the form of Henry's various assizes and the growth of case law.[62][63] In 1166, the Assize of Clarendon established the supremacy of royal courts over manorial and ecclesiastical courts.[64] Henry's legal reforms also transformed the king's personal role in the judicial process into an impersonal legal bureaucracy. The 1176 Assize of Northampton divided the kingdom into six judicial circuits called eyres allowing itinerant royal judges to reach the whole kingdom.[65] In 1178, the king ordered five members of his curia regis to remain at Westminster and hear legal cases full time, creating the Court of King's Bench. Writs (standardised royal orders with the great seal attached) were developed to deal with common legal problems. Any freeman could purchase a writ from the chancery and receive royal justice without the king's personal intervention.[66] For example, a writ of novel disseisin commanded a local jury to determine whether someone had been unjustly dispossessed of land.[65]

Since William the Conqueror's separation of secular and ecclesiastical jurisdiction, church courts claimed exclusive authority to try clergy, including monks and clerics in minor orders. The most contentious issue was "criminous clerks" accused of theft, rape or murder. Church courts could not impose the death penalty or bodily mutilation, and their punishments (penance and defrocking) were lenient. In 1164, Henry issued the Constitutions of Clarendon, which required criminous clerks who had been defrocked to be handed over to royal courts for punishment as laymen. It also forbade appeals to the pope. Archbishop Thomas Becket opposed the Constitutions, and the Becket controversy culminated in his murder in 1170. In 1172, Henry reached a settlement with the church in the Compromise of Avranches. Appeals to Rome were allowed, and secular courts were given jurisdiction over clerics accused of non-felony crimes.[67][68]

Henry also extended his authority outside of England. In 1157, he invaded Wales and received the submission of Owain of Gywnedd and Rhys ap Gruffydd of Deheubarth.[69] The Scottish king William the Lion was forced to acknowledge the English king as feudal overlord[note 2] in the Treaty of Falaise.[71] The 1175 Treaty of Windsor confirmed Henry as feudal overlord of most of Ireland.[72]

Richard the Lionheart

.svg.png.webp)

Upon Henry's death, his eldest surviving son Richard I (r. 1189–1199), nicknamed the Lionheart, succeeded to the throne. As king, he spent a total of six months in England.[73] In 1190, the king left England with a large army and fleet to join the Third Crusade to reconquer Jerusalem from Saladin. Richard funded this campaign through taxation (such as the Saladin tithe) as well as selling offices, titles, and land.[74] In his absence, England was governed by William de Longchamp, in whom was consolidated both secular and ecclesiastical power as Bishop of Ely, papal legate, justiciar and chancellor.[75]

Concerned that John would usurp power while he was on Crusade, Richard made his brother swear to leave England for three years. John broke his oath and was in England by April 1191 leading opposition against Longchamp. From Sicily, Richard sent Archbishop Walter de Coutances to England as his envoy to resolve the situation. In October, a group of barons and bishops led by the Archbishop deposed Longchamp. John was appointed regent, but real power was exercised by Coutances as justiciar.[76]

While returning from Crusade, Richard was imprisoned by Holy Roman Emperor Henry VI for over a year and was not released until England paid an enormous ransom.[77] In 1193, John defected to Philip II of France, and the two plotted to take Richard's lands on the Continent.[78] After a four-year absence, Richard returned to England in March 1194, but he soon left again to wage war against Philip II, who had overrun the Vexin and parts of Normandy.[79] By 1198, Richard had reconquered most of his territory. At the Battle of Gisors, Richard adopted the motto Dieu et mon droit (French for "God and my Right"), which was later adopted as the royal motto.[80] In 1199, Richard died from wounds received while besieging Châlus-Chabrol. Before his death, the king made peace with John, naming him his successor.[81]

After Richard's return from Crusade, the king created the office of coroner (from custos placitorum coronae, Latin for "keeper of the pleas of the Crown"). The coroner, alongside the sheriff, was a royal officer responsible for administering justice within a shire.[82]

John

At Westminster Abbey in May 1199, John (r. 1199–1216) was crowned Rex Angliae (Latin for "King of England") rather than the older form of Rex Anglorum (Latin for "King of the English").[83] In 1204, John lost Normandy and his other Continental possessions. The remainder of his reign was shaped by attempts to rehabilitate his military reputation and fund wars of reconquest.[84] Traditionally, the king was expected to fund his government out of his own income derived from the royal demesne, profits of royal justice, and profits from the feudal system (such as feudal incidents, reliefs, and aids). In reality, this was rarely possible, especially in time of war.[85] To fund his campaigns, John introduced a thirteen percent tax on revenues and movable goods that would become the model for taxation through the Tudor period. The king also raised money by charging high court fees and—in the opinion of his barons—abusing his right to feudal incidents and reliefs.[86] Scutages were levied almost annually, much more often than under earlier kings. In addition, John showed partiality and favouritsm when dispensing justice. This and his paranoia caused his relationship with the barons to break down.[87]

After quarreling with the king over the election of a new Archbishop of Canterbury, Pope Innocent III placed England under papal interdict in 1208. For the next six years, priests refused to say mass, officiate marriages, or bury the dead. John responded by confiscating church property.[88] In 1209, the pope excommunicated John, but he remained unrepentant. It was not until 1213 that John reconciled with the pope, going so far as to convert the Kingdom of England into a papal fief with John as the pope's vassal.[89]

The Anglo-French War of 1213–1214 was fought to restore the Angevin Empire, but John was defeated at the Battle of Bouvines. The military and financial losses of 1214 severely weakened the king, and the barons demanded that he govern according to Henry I's Coronation Charter. On 5 May 1215, a group of barons renounced their fealty to John calling themselves the Army of God and the Holy Church and chose Robert Fitzwalter to be their leader.[note 3] The rebels numbered about 40 barons together with their sons and vassals. The other barons—around a hundred—worked with Archbishop Langton and the papal legate Guala Bicchieri to effect compromise between the two sides.[91] Over a month of negotiations resulted in the Magna Carta (Latin for "Great Charter"), which was formally agreed to by both sides at Runnymede on 15 June. This document defined and limited the king's powers over his subjects. It would be reconfirmed throughout the 13th century and gain the status of "inalienable custom and fundamental law".[92] Historian Dan Jones notes that:

_-_BL_Cotton_MS_Augustus_II_106.jpg.webp)

Whereas many of the clauses in the charter were formal terms pertaining to specific policies pursued by John—whether with regard to raising armies, levying taxes, impeding merchants, or arguing with the Church—the most famous clauses aimed at a deeper elaboration of the rights of subjects to set out the limits of central government. Clause 39 reads: "No free man shall be taken or imprisoned or disseised or outlawed or exiled or in any way ruined ... except by lawful judgment of his peers or by the law of the land." Clause 40 is more laconic: "To no one will we sell, to no one will we deny or delay right or justice." These clauses addressed the whole spirit of John's reign and by extension the spirit of kingship itself. For the eleven years in which John had resided in England, his barons had tasted a form of tyranny. John had used his powers in an arbitrary, partisan, and exploitative fashion and had used the processes of law deliberately to weaken and menace his noble lords. He had broken the spirit of kingship as presented by Henry II back in 1153, when he traveled the country offering unity and legal process to all.[93]

Unlike earlier charters of liberties, Magna Carta included an enforcement mechanism in the form of a council of 25 barons who were permitted to wage "lawful rebellion" against the king if he violated the charter. The king had no intention of adhering to the document and appealed to Pope Innocent who annulled the agreement and excommunicated the rebel barons. This began the First Barons' War, during which the rebels offered the crown to Philip II's son, the future Louis VIII of France.[note 4] By June 1216, Louis had taken control of half of England, including London. While he had not been crowned, he was proclaimed King Louis I at St Paul's Cathedral, and many English nobles along with King Alexander II of Scotland gave him homage. In the midst of this collapse of royal authority, John died abruptly at Newark Castle on 19 October.[95]

Henry III

.JPG.webp)

After John's death, loyal barons and bishops took his nine-year-old son to Gloucester Abbey where he was crowned Henry III (r. 1216–1272) in a rushed coronation. This established the precedent that the eldest son became king regardless of age.[96] Henry was the first child king since Æthelred the Unready,[97] and William Marshal, Earl of Pembroke, served as regent until his death in 1219. Marshal led royal forces to victory against the rebel barons and French invaders at the Battles of Lincoln and Sandwich in 1217.[98]

During Henry's reign, the principle that kings were subject to the law gained acceptance.[99] To build support for the new king, his government re-issued Magna Carta in 1216 and 1217 (along with the Charter of the Forest).[100] In January 1225, the Magna Carta was re-issued at a Great Council in return for approval of a tax to fund military campaigns in France. This established a new constitutional precedent in which "military expeditions would be financed at the expense of detailed concessions of political liberties".[101] In 1236, Henry began calling such meetings Parliament. By the 1240s, these early Parliaments had not only assumed power to grant taxes but were also venues where nobles could complain about government policy or corruption.[102]

In 1227, Henry was eighteen years old, and the regency officially ended. Yet, throughout his personal rule the king displayed a tendency to be dominated by foreign favourites. After the fall of the justiciar Hubert de Burgh in 1230, Bishop Peter des Roches became the king's chief minister. While holding no great office himself, the bishop showered his Poitevin relation Peter de Rivaux with a large number of offices.[103] He was placed in charge of the treasury, the privy seal, and the royal wardrobe. At the time, the wardrobe was a department that was at the centre of financial and political decisions in the royal household. He was given financial control of the royal household for life, was keeper of the forests and ports, and was, in addition, the sheriff of twenty-one counties. Rivaux used his immense power to enact important administrative reforms.[104] Nevertheless, the accumulation of power by foreigners led Richard Marshal to open rebellion. The bishops as a group threatened Henry with excommunication, which finally made him strip the Poitevin party of power.[105]

Henry then transferred his favouritism to his Lusignan half-brothers, William and Aymer de Valence. By the 1250s, there was widespread resentment against the Lusignans. There was also opposition to Henry's unrealistic plans to conquer the Kingdom of Sicily for his second son, Edmund Crouchback. In 1255, the king informed Parliament that as part of the Sicilian campaign he owed the pope the huge sum of £100,000 (equal to £132,431,068 today) and that if he defaulted England would be placed under an interdict. By 1257, there was a growing consensus that Henry was unfit to rule.[106][107][108]

In 1258, the king was forced to submit to a radical reform programme promulgated at the Oxford Parliament. The Provisions of Oxford transferred royal power to a council of fifteen barons. A parliament would meet three times a year and appoint all royal officers (from justiciar and chancellor to sheriffs and bailiffs). The new government's leader was Simon de Montfort, the king's brother-in-law and former friend. By the terms of the 1295 Treaty of Paris, the English Crown gave up all claims to Normandy and Anjou in return for keeping the Duchy of Aquitaine as a vassal of the French king.[109]

When the king tried to overturn the Provisions of Oxford, Montfort led a rebellion, the Second Barons' War. In 1265, Montfort called a Parliament to consolidate support for the rebellion. For the first time, knights of the shire and burgesses from the important towns were summoned along with barons and bishops. Simon de Montfort's Parliament was an important milestone in the evolution of Parliament. Montfort was killed at the Battle of Evesham in 1265, and royal authority was restored.[110]

Henry traveled less than past kings. As a consequence, he spent large amounts of money on royal palaces. His most expensive projects were the rebuilding of Westminster Palace and Abbey, costing £55,000 (equal to £44,130,706 today). He spent a further £9,000 (equal to £7,221,388 today) on the Tower of London.[111][108] Westminster Abbey alone nearly bankrupted the king.[112]

Henry III died in 1272, having been king for fifty-six years. His turbulent reign was the third longest of any English monarch.[110]

Edward I

.jpg.webp)

Edward I (r. 1272–1307), nicknamed Longshanks for his height, was in Italy when he learned that his father had died. Previous monarchs were only legally recognised as king after coronation, but Edward's reign officially began on 20 November, the same day his father was buried at Westminster Abbey. Walter Giffard, archbishop of York; Roger Mortimer, a marcher lord; and Robert Burnell were appointed regents. A proclamation issued on 23 November that stated:[114]

The government of the realm has come to the king on the death of King Henry his father, by hereditary succession and by the will of the magnates of the realm and by their fealty done to the king, wherefore the magnates have caused the king's peace to be proclaimed in the king's name.

Edward returned to England in August 1274 determined to restore royal authority. His first act was ordering the Hundred Rolls survey, a detailed investigation into what rights and land the Crown had lost since Henry III's reign. It was also intended to root out corruption by royal officials, and while few people were prosecuted for wrongdoing, it sent a message that Edward was a reformer.[115]

From his father's reign, Edward learned the importance of building national consensus for his policies through Parliament, which he usually summoned twice a year at Easter and Michaelmas. Edward effected his reform program through a series of parliamentary statutes: Statute of Westminster of 1275, Statute of Gloucester of 1278, Statute of Mortmain of 1279, Statute of Acton Burnell of 1283, and Statute of Westminster of 1285. In 1297, he reissued Magna Carta.[116][117] In 1295, Edward summoned the Model Parliament, which included knights and burgesses to represent the counties and towns. These "middle earners" were the most important group of taxpayers, and Edward was eager to gain their financial support for an invasion of Scotland.[118]

Through effective management of Parliament, Edward was able to fund his military campaigns in Wales and Scotland. He successfully and permanently conquered Wales, built impressive castles to enforce English domination, and brought the country under English law with the Statute of Wales. In 1301, the king's eldest son, Edward of Caernarfon, was created Prince of Wales and given control of the Principality of Wales. The title continues to be granted to the heirs of British monarchs.[119]

The death of Alexander III of Scotland in 1286 and his granddaughter Margaret of Norway in 1290 left the Scottish throne vacant. The Guardians of Scotland recognised Edward's feudal overlordship and invited him to adjudicate the Scottish succession dispute. In 1292, John Balliol was chosen Scotland's new king, but Edward's brutal treatment of his northern vassal led to the First War of Scottish Independence. In 1307, Edward died on his way to invade Scotland.[120]

Edward II

At his coronation, Edward II (r. 1307–1327) promised not only to uphold the laws of Edward the Confessor as was traditional but also "the laws and rightful customs which the community of the realm shall have chosen".[121] Edward thus abandoned any claim to absolute power and recognised the need to rule in cooperation with Parliament.[122] The new king inherited problems from his father: the Crown was in debt and the war in Scotland was going badly. He compounded these problems by alienating the nobility. The main cause of conflict was the influence wielded by royal favourites, first Piers Gaveston and then Hugh Despenser the Younger.[123]

The king's reliance on favourites proved a convenient scapegoat for the barons, who blamed unpopular policies on them rather than directly oppose the king.[124] When Parliament met in April 1308, Henry de Lacy, Earl of Lincoln, and a delegation of nobles presented the Declaration of 1308, which for the first time explicitly distinguished between the king as a person and the Crown as an institution to which the people owed allegiance. This distinction was known as the doctrine of capacities.[125]

In 1310, Parliament complained that "the state of the king and the kingdom had much deteriorated since the death of the elder King Edward ... and the whole kingdom had been not a little injured".[126] Specifically, Edward was accused of being guided by evil counselors, impoverishing the Crown, violating Magna Carta, and losing Scotland. The magnates elected twenty-one ordainers to reform the government. The completed reforms were presented to Edward as the Ordinances in August 1311. Like Magna Carta and the Provisions of Oxford, the Ordinances of 1311 were an attempt to limit the powers of the monarch. It banned the practice of purveyance and going to war without consulting Parliament. Government revenue was to be paid to the exchequer rather than to the royal household, and Parliament was to meet at least once a year. Parliament was to create committees to investigate royal abuses and to appoint royal ministers and officials (such as the chancellor and county sheriffs).[127]

The Ordinances also required the exile of the king's favourite, Gaveston. By January 1312, Edward had publicly repudiated the ordinances, and Gaveston was back in England.[128] Earl Thomas of Lancaster, the king's cousin, led a group of magnates that captured and executed Gaveston.[note 5] This act nearly plunged England into civil war but negotiations restored an uneasy peace.[130]

After Gaveston's death, the most influential men around the king were Hugh Despenser and his son, Hugh Despenser the Younger. The king alienated moderate barons by dispensing royal patronage without parliamentary approval as required by the Ordinances and allowing the Despensers to act with impunity. In 1318, negotiations led to the Treaty of Leake in which the king agreed to abide by the Ordinances of 1311. A permanent royal council was created with eight bishops, four earls, and four barons as members.[131]

Edward's favouritsm toward the Despensers continued to destabilize the kingdom. The Despensers had become the gatekeepers to the king, and their enemies "were liable to be deprived of land or possessions or else thrown into prison".[132] The Welsh Marches were particularly destabilized by Hugh the Younger's accumulation of land. In 1321, a group of marcher lords invaded the Despenser estates, beginning the Despenser War.[133] Edward defeated the baronial opposition in 1322 and overturned the Ordinances.[134] For the next few years, Edward ruled as a tyrant. The author of the Vita Edwardi Secundi wrote of this period,[135]

parliaments, colloquies, and councils decide nothing these days. For the nobles of the realm, terrified by threats and the penalties inflicted on others, let the king's will have free play. Thus today will conquers reason. For whatever pleases the king, though lacking in reason, has the force of law.

In 1324, Edward's wife Isabella and their son, Prince Edward, traveled to France on a diplomatic mission. While there, the Queen formed an alliance with Roger Mortimer, a marcher lord who had fought against Edward in the Despenser War. At the head of a mercenary army, they invaded England in 1326. Important noblemen defected to the Queen's cause, and London rose in revolt. Meanwhile, the King and the Dispensers fled to Wales. On October 26, Isabella and Mortimer proclaimed that in the King's absence power temporarily resided with the fourteen-year-old Prince Edward. Having been abandoned by most of his household, the King was captured on 16 November.[136]

By this point, it was clear that Edward II could not remain king, but this precipitated a constitutional crisis as there was no legal process to remove a crowned and anointed king who in theory was the source of all public authority.[137] At the Parliament of 1327, the Articles of Accusation were drawn up accusing the King of violating his coronation oath and following the advice of evil councilors. On 20 January, Edward II was forced to abdicate. This marked the first time in English history that a monarch was formally deposed from the throne. The former king died on 21 September, probably murdered on the orders of his wife.[138][139]

Edward III

Five days after his father's abdication, the fourteen-year-old Edward III (r. 1327–1377) was crowned king, but it was Isabella and Mortimer who truly held power. Under their three-year rule, the monarchy was weakened abroad and at home. They made a disadvantageous treaty with France and failed to press Edward's claim to the French throne when his uncle, Charles IV, died without a male heir. They also agreed to the Treaty of Edinburgh–Northampton, which forfeited England's claim to overlordship of Scotland. At home, Mortimer used his new power to enrich himself even as the Crown faced bankruptcy and the nation experienced a rise in crime and violence. In 1330, Mortimer had Edmund of Woodstock, the King's uncle, arrested and executed for treason.[141]

On 19 October 1330, the seventeen-year-old Edward staged a coup at Nottingham Castle with the help of William Montagu and around 16 other young household companions. Mortimer was arrested, tried before Parliament, and executed for treason.[142] The young King, now in full control of his kingdom, realised that he could not afford to alienate the English nobility. He cultivated "an aristocratic culture, which bound the king and nobles together."[143] In particular, royal-noble bonds were strengthened through frequent tournaments in which Edward himself would take part.[144] Edward was the first king since the Conquest to speak English, and during his reign Middle English began to replace French as the language of the aristocracy.[145]

In 1333, Edward invaded Scotland winning a major victory at the Battle of Halidon Hill due to the use of the English longbow.[146] The victory allowed Edward to place Edward Balliol on the Scottish throne with himself as overlord. With French help, the Scots loyal to David II continued to resist English interference in the Second War of Scottish Independence.[147]

.svg.png.webp)

In March 1337, Edward created six new earldoms in order to gain military support for a war against France. His eldest son, the six-year-old Edward of Woodstock, was made Duke of Cornwall, the first duchy created in England. In May 1337, King Philip VI of France confiscated the Duchy of Aquitaine and the County of Ponthieu from the English king. In 1340, Edward claimed the French throne on the grounds that he was the last male descendent of his grandfather, Philip IV of France. To symbolise his claim, the King added the fleur-de-lis to the royal arms of England.[148][149]

In 1346, Edward invaded France in pursuit of his claim, setting off the Hundred Years' War which would last until 1453. The English won the Battle of Crécy and after a siege took the town of Calais, which would remain an English possession for the next two centuries. After a successful campaign in France, Edward returned to England and founded the Order of the Garter at Windsor Castle in 1348.[150] Between 1350 and 1377, Edward spent £50,000 (equal to £42,100,000 today)[108] transforming Windsor from an ordinary castle into a "palatial castle of quite extraordinary splendour".[151]

The King's eldest son Edward, known to history as the Black Prince, won the Battle of Poitiers in 1356 in which the French king John II was captured.[145] In the Treaty of Brétigny of 1360, Edward renounced his claims to the French throne and was awarded outright sovereignty over Calais, Ponthieu, and Aquitaine. Edward also negotiated a peace with Scotland that included the release of David II in return for recognising the English king's overlordship of Scotland.[152]

Edward worked with Parliament to build consensus and support for his wars and, in the process, furthered Parliament's development as an essential institution of government. According to historian David Starkey,[153]

Edward was willing to do whatever was necessary to persuade members of Parliament to dig their hands deep into their constituents' pockets. It meant doing deals, greasing palms, slapping backs. Edward's victories were reported in detail; Parliament was consulted on war diplomacy and ratified the peace treaties with France ... The length of Edward's wars also normalized taxation. Direct taxation, on income and property, continued to be voted only for war. But indirect taxation on trade became permanent, enhancing royal power and extending the scope of royal government.

.jpg.webp)

There were a number of setbacks in the last years of Edward's reign. The new French king Charles V successfully drove the Black Prince out of Aquitaine. Prince Edward returned to England in 1371 bankrupt and in declining health possibly caused by dysentery. The infirmity of both the elderly King and Prince Edward created a power vacuum that John of Gaunt tried to fill, but there were many complaints of corruption and mismanagement in government. In the Good Parliament of 1376, the House of Commons refused to finance the war with France until corrupt ministers and Alice Perrers, the royal mistress, were removed. Having little choice, the King acquiesced and the accused ministers were arrested and brought to trial before Parliament in the first impeachment proceedings. While the Good Parliament was still in session, the Black Prince died at the age of 45.[154]

Edward's new heir was his nine-year-old grandson Richard of Bordeaux. There were concerns that Richard's uncles might usurp power. To strengthen the boy's position, he was recognised in Parliament as heir apparent and given the titles of prince of Wales, duke of Cornwall, and earl of Chester. Having secured the succession, Edward III died in 1377.[155]

Richard II

Richard II (r. 1377–1399) was ten years old when he became king. Despite the king's youth, no regency was set up to govern during his minority since his uncle John of Gaunt, duke of Lancaster (the most likely candidate for regent) was unpopular. Instead, Richard theoretically ruled in his own right with the advice of a 12-member advisory council. In reality, the government was dominated by the king's uncles, especially Gaunt, and courtiers, such as Simon Burley, Guichard d'Angle, and Aubrey de Vere.[156][157] In 1381, resentment over poll taxes led to the Peasants' Revolt. The fourteen-year-old king's brave and decisive leadership in ending the revolt demonstrated he was ready to assume actual power. But the revolt also left a deep impression on Richard, "convincing him that disobedience, no matter how justified, constituted a threat to order and stability within his realm and must not be tolerated."[158]

After the revolt, Parliament appointed Michael de la Pole to advise the King. Pole proved himself a loyal servant and was made chancellor in 1383 and earl of Suffolk in 1385. The King's most important favourite, however, was Robert de Vere, the earl of Oxford. In 1385, de Vere was given the novel title of marquess and placed above all earls and below only the royal dukes in rank. In 1386, de Vere was made duke of Ireland, the first duke not of royal blood. This favouritism alienated other aristocrats, including the King's uncles.[159][160]

Another cause for complaint was the situation in France. The English retained only Calais and a small part of Gascony while French ships harassed English traders in the Channel. Richard personally led an invasion of Scotland in 1385 that achieved nothing. Meanwhile, he spent lavishly on palace renovations and court entertainments.[161] One historian described Richard's government as "a high-tax, high-spend, cliquey affair."[162]

In 1386, Pole requested additional funds to defend England against a potential French invasion, but under the leadership of Richard's uncle Thomas of Woodstock, the Wonderful Parliament refused to act until Pole was removed as chancellor.[163] Richard refused at first but gave in after being threatened with deposition. A council was set up to audit royal finances and exercise royal authority. At 19 years old, the King was once again reduced to a figurehead.[164] Defiant, Richard left London for a "gyration" (tour) of the country to gather an army.[165]

Richard returned to London in November 1387 and was approached by three nobles: his uncle Thomas, duke of Gloucester; Richard Fitzalan, earl of Arundel; and Thomas Beauchamp, earl of Warwick. These Lords Appellant (as they became known) appealed (or indicted) Pole, de Vere, and other close associates of the King with treason.[166] The Lords Appellant defeated Richard's army at the Battle of Radcot Bridge, and the King had no choice but to submit to their wishes. At the Merciless Parliament of 1388, Richard's favourites were convicted of treason.[163]

After the royal favourites had been removed, the Lords Appellant were content. In 1389, Richard resumed royal authority and reconciled with John of Gaunt, who used his influence on Richard's behalf.[168] For a time, Richard ruled well. The King led a successful expedition to Ireland in 1394 and negotiated a 28-year truce with France in 1396.[169] In July 1397, Richard was finally ready to move against his enemies. The three Lords Appellant were arrested. When Parliament met at Westminster, the presence of 300 of Richard's Cheshire archers made it clear that no dissent would be tolerated. Chancellor Edmund Stafford, bishop of Exeter, preached the opening sermon on Ezekiel 37:22, "There shall be one king over them all".[170] The Lords Appellant were then tried and found guilty of treason.[171]

For the next two years, Richard ruled as a tyrant, using extortion to gain forced loans from his subjects.[172] The twice-married king was childless and the succession was uncertain. The man with the strongest claim was John of Gaunt, whose son and heir was Henry Bolingbroke.[171] In 1397, a dispute between Bolingbroke and Thomas Mowbray led to the former's banishment from England for 10 years.[173] When John of Gaunt died in 1399, Richard confiscated the Duchy of Lancaster and extended Bolingbroke's banishment for life.[174]

In May 1399, Richard embarked on a second invasion of Ireland, taking most of his followers with him. Bolingbroke returned to England in July with a small force of men but quickly gained the support of powerful nobles, such as Henry Percy, the earl of Northumberland and most powerful man in northern England.[175][176] Richard returned to England, but his army and supporters rapidly melted away. By 2 September, Richard was a prisoner in the Tower.[174]

On 30 September, an assembly of the House of Lords and House of Commons met in Westminster Hall (later referred to as a convention parliament, it technically was not a parliament because it met without royal authority). Richard Scrope, archbishop of York, stated that Richard, who was not present, had agreed to abdicate. When Thomas Arundel, archbishop of Canterbury, asked if the Lords and Commons accepted this each lord agreed and the Commons shouted their agreement.[177] Thirty-nine articles of deposition were read out in which Richard was charged with breaking his coronation oath and violating "the rightful laws and customs of the realm".[178] After John Trevor, bishop of St. Asaph, announced Richard's deposition, Bolingbroke gave a speech claiming the Crown. The archbishops of Canterbury and York each took one of Bolingbroke's arms and seated him on the empty throne to shouts of acclimation from the Lords and Commons.[179]

Richard II was not the first English monarch to be deposed; that distinction belongs to Edward II. Edward abdicated in favor of his son and heir. In Richard's case, the line of succession was deliberately broken by Parliament. Historian Tracy Borman writes that this "created a dangerous precedent and made the crown fundamentally unstable."[180]

House of Lancaster (1399–1461)

Henry IV

Bolingbroke was crowned as Henry IV (r. 1399–1413) two weeks after Richard II's deposition. His dynasty was known as the House of Lancaster, a reference to his father's title Duke of Lancaster. As part of the coronation, Henry created Knights of the Bath, a tradition that was repeated at all later coronations. He was also the first English monarch to be crowned on the Stone of Scone, which Edward I had taken from Scotland.[181]

In January 1400, the Epiphany Rising unsuccessfully tried to free Richard and restore him to the throne. Henry realized he would have no security as long as Richard lived, so he ordered his death, most likely by starvation.[182] Henry's reign was forever tarnished by the deposition and murder of an anointed king, and he constantly had to fight off plots and rebellions. In 1400, the Welsh Revolt began, and Henry Hotspur of the powerful Percy family joined the revolt in 1403. Hotspur was defeated at the Battle of Shrewsbury, but King Henry continued to face challenges to his legitimacy.[183]

When overthrowing Richard, Henry had promised to reduce taxation, and Parliament held him to that promise, refusing to raise taxes even as the king went into debt fighting defensive wars. Financially, Henry benefited from inheriting the vast Lancastrian estates of his father. He decided to administer these lands separately from the crown lands.[184] The practice of holding the Duchy of Lancaster separate from the crown estate was continued by later monarchs.

Charles VI of France, Richard's father-in-law, refused to recognise Henry. The French revived their claims to Aquitaine, attacked Calais, and aided the Welsh Revolt. But in 1407, the Armagnac–Burgundian Civil War divided France, and the English were keen to take advantage of French disunity. English policy vacillated toward the opposing sides as King Henry supported the Armagnac faction, while his eldest son, Henry of Monmouth, supported the Burgundian faction. As the king's health declined, Monmouth assumed a greater role in government, and there were suggestions that the king should abdicate in favor of his son.[185]

Henry V

Abdication became unnecessary when Henry IV died in 1413, and the prince became King Henry V (r. 1413–1422). He escaped the troubles of his father's reign by making conciliatory gestures toward his father's enemies. He also removed the taint of usurpation by honoring the deceased Richard II and giving him a royal re-burial at Westminster Abbey.[185]

As a result of his unifying gestures, Henry V's reign was largely free from domestic strife, leaving the king free to pursue the last phase of the Hundred Years' War with France. The war appealed to English national pride,[186] and Parliament readily granted a double subsidy to finance the campaign, which began in August 1415. In this first campaign, Henry won a legendary victory at the Battle of Agincourt.[187] The triumphant king returned home to a jubilant nation eager to support further wars of conquest. Parliament gave the king lifetime duties on wine imports and other tax grants. When he was ready to return to France, Parliament granted another double subsidy.[188]

In 1419, he conquered Normandy—the first time an English king ruled Normandy since King John lost it in 1204.[189] In 1420, the Treaty of Troyes recognised Henry as heir and regent of the incapacitated King Charles VI of France. The new peace was sealed by Henry's marriage to the French princess Catherine of Valois. Charles's son, the Dauphin, was disinherited by the treaty; however, he continued to assert his right to the French throne and remained in control of over half of France south of the Loire river.[190]

Henry V was a popular king who restored royal authority and lowered crime. Despite high taxes, England prospered under Henry V. He kept his personal expenses low and managed royal finances well.[191] But Henry's frequent absences from England did create difficulties. While in France, Henry insisted on dealing with petitions from Parliament personally despite the long distances and delays involved. By 1420, the House of Commons was complaining, and funds for further wars in France were more difficult to secure. On 31 August 1422, the king fell ill and died while on another campaign in France.[190]

Henry VI

Only nine months old when his father died, Henry VI was the youngest person to ever inherit the English crown. On 21 October 1422, Charles VI of France died. The infant Henry was now king of England and France according to the terms of the Treaty of Troyes. The union of the two kingdoms under the same ruler is called the dual monarchy.[192]

In his will, Henry V placed his brother John, duke of Bedford, in charge of France. In England, his other brother Humphrey, duke of Gloucester, was made lord protector[note 6] and head of a regency council that exercised authority in the king's name (see Regency government, 1422–1437).[194]

The accession of Henry V's infant son, Henry VI, to the throne gave the French an opportunity to overthrow English rule.[195] The unpopularity of Henry VI's counsellors and his consort, Margaret of Anjou, as well as his own ineffectual leadership, led to the weakening of the House of Lancaster. The Lancastrians faced a challenge from the House of York, so-called because its head, a descendant of Edward III, was Richard, Duke of York, who was at odds with the Queen.

House of York (1461–1485)

Although the Duke of York died in battle in 1460, his eldest son, Edward IV, led the Yorkists to victory in 1461, overthrowing Henry VI and Margaret of Anjou. Edward IV was constantly at odds with the Lancastrians and his own councillors after his marriage to Elizabeth Woodville, with a brief return to power for Henry VI. Edward IV prevailed, winning back the throne at Barnet and killing the Lancastrian heir, Edward of Westminster, at Tewkesbury. Afterward he captured Margaret of Anjou, eventually sending her into exile, but not before killing Henry VI while he was held prisoner in the Tower. The Wars of the Roses, nevertheless, continued intermittently during his reign and those of his son Edward V and brother Richard III. Edward V disappeared, presumably murdered by Richard. Ultimately, the conflict culminated in success for the Lancastrian branch led by Henry Tudor, in 1485, when Richard III was killed in the Battle of Bosworth Field.[196]

Tudors (1485–1603)

King Henry VII then neutralised the remaining Yorkist forces, partly by marrying Elizabeth of York, a Yorkist heir. Through skill and ability, Henry re-established absolute supremacy in the realm, and the conflicts with the nobility that had plagued previous monarchs came to an end.[197][198] The reign of the second Tudor king, Henry VIII, was one of great political change. Religious upheaval and disputes with the Pope, and the fact that his marriage to Catherine of Aragon produced only one surviving child, a daughter, led the monarch to break from the Roman Catholic Church and to establish the Church of England (the Anglican Church) and divorce his wife to marry Anne Boleyn.[199]

Wales – which had been conquered centuries earlier, but had remained a separate dominion – was annexed to England under the Laws in Wales Acts 1535 and 1542.[200] Henry VIII's son and successor, the young Edward VI, continued with further religious reforms, but his early death in 1553 precipitated a succession crisis. He was wary of allowing his Catholic elder half-sister Mary I to succeed, and therefore drew up a will designating Lady Jane Grey as his heiress. Jane's reign, however, lasted only nine days; with tremendous popular support, Mary deposed her and declared herself the lawful sovereign. Mary I married Philip of Spain, who was declared king and co-ruler. He pursued disastrous wars in France and she attempted to return England to Roman Catholicism (burning Protestants at the stake as heretics in the process). Upon her death in 1558, the pair were succeeded by her Protestant half-sister Elizabeth I. England returned to Protestantism and continued its growth into a major world power by building its navy and exploring the New World.[201][202]

Scottish monarchy

In Scotland, as in England, monarchies emerged after the withdrawal of the Roman empire from Britain in the early fifth century. The three groups that lived in Scotland at this time were the Picts in the north east, the Britons in the south, including the Kingdom of Strathclyde, and the Gaels or Scotti (who would later give their name to Scotland), of the Irish petty kingdom of Dál Riata in the west. Kenneth MacAlpin is traditionally viewed as the first king of a united Scotland (known as Scotia to writers in Latin, or Alba to the Scots).[203] The expansion of Scottish dominions continued over the next two centuries, as other territories such as Strathclyde were absorbed.

Early Scottish monarchs did not inherit the Crown directly; instead, the custom of tanistry was followed, where the monarchy alternated between different branches of the House of Alpin. As a result, however, the rival dynastic lines clashed, often violently. From 942 to 1005, seven consecutive monarchs were either murdered or killed in battle.[204] In 1005, Malcolm II ascended the throne having killed many rivals. He continued to ruthlessly eliminate opposition, and when he died in 1034 he was succeeded by his grandson, Duncan I, instead of a cousin, as had been usual. In 1040, Duncan suffered defeat in battle at the hands of Macbeth, who was killed himself in 1057 by Duncan's son Malcolm. The following year, after killing Macbeth's stepson Lulach, Malcolm ascended the throne as Malcolm III.[205]

With a further series of battles and deposings, five of Malcolm's sons as well as one of his brothers successively became king. Eventually, the Crown came to his youngest son, David I. David was succeeded by his grandsons Malcolm IV, and then by William the Lion, the longest-reigning King of Scots before the Union of the Crowns.[206] William participated in a rebellion against King Henry II of England but when the rebellion failed, William was captured by the English. In exchange for his release, William was forced to acknowledge Henry as his feudal overlord. The English King Richard I agreed to terminate the arrangement in 1189, in return for a large sum of money needed for the Crusades.[207] William died in 1214, and was succeeded by his son Alexander II. Alexander II, as well as his successor Alexander III, attempted to take over the Western Isles, which were still under the overlordship of Norway. During the reign of Alexander III, Norway launched an unsuccessful invasion of Scotland; the ensuing Treaty of Perth recognised Scottish control of the Western Isles and other disputed areas.[208]

Alexander III's death in a riding accident in 1286 precipitated a major succession crisis. Scottish leaders appealed to King Edward I of England for help in determining who was the rightful heir. Edward chose Alexander's three-year-old Norwegian granddaughter, Margaret. On her way to Scotland in 1290, however, Margaret died at sea, and Edward was again asked to adjudicate between 13 rival claimants to the throne. A court was set up and after two years of deliberation, it pronounced John Balliol to be king. Edward proceeded to treat Balliol as a vassal, and tried to exert influence over Scotland. In 1295, when Balliol renounced his allegiance to England, Edward I invaded. During the first ten years of the ensuing Wars of Scottish Independence, Scotland had no monarch, until Robert the Bruce declared himself king in 1306.[209]

Robert's efforts to control Scotland culminated in success, and Scottish independence was acknowledged in 1328. However, only one year later, Robert died and was succeeded by his five-year-old son, David II. On the pretext of restoring John Balliol's rightful heir, Edward Balliol, the English again invaded in 1332. During the next four years, Balliol was crowned, deposed, restored, deposed, restored, and deposed until he eventually settled in England, and David remained king for the next 35 years.[210]

David II died childless in 1371 and was succeeded by his nephew Robert II of the House of Stuart. The reigns of both Robert II and his successor, Robert III, were marked by a general decline in royal power. When Robert III died in 1406, regents had to rule the country; the monarch, Robert III's son James I, had been taken captive by the English. Having paid a large ransom, James returned to Scotland in 1424; to restore his authority, he used ruthless measures, including the execution of several of his enemies. He was assassinated by a group of nobles. James II continued his father's policies by subduing influential noblemen but he was killed in an accident at the age of thirty, and a council of regents again assumed power. James III was defeated in a battle against rebellious Scottish earls in 1488, leading to another boy-king: James IV.[211]

In 1513 James IV launched an invasion of England, attempting to take advantage of the absence of the English King Henry VIII. His forces met with disaster at Flodden Field; the King, many senior noblemen, and hundreds of soldiers were killed. As his son and successor, James V, was an infant, the government was again taken over by regents. James V led another disastrous war with the English in 1542, and his death in the same year left the Crown in the hands of his six-day-old daughter, Mary. Once again, a regency was established.

Mary, a Roman Catholic, reigned during a period of great religious upheaval in Scotland. As a result of the efforts of reformers such as John Knox, a Protestant ascendancy was established. Mary caused alarm by marrying her Catholic cousin, Lord Darnley, in 1565. After Lord Darnley's assassination in 1567, Mary contracted an even more unpopular marriage with the Earl of Bothwell, who was widely suspected of Darnley's murder. The nobility rebelled against the Queen, forcing her to abdicate. She fled to England, and the Crown went to her infant son James VI, who was brought up as a Protestant. Mary was imprisoned and later executed by the English queen Elizabeth I.[212]

Irish monarchy

Ireland was historically divided into petty principalities that sometimes acknowledged one of their rulers as High King of Ireland. In 1155, the only English pope, Adrian IV, authorised Henry II of England to conquer Ireland and reform the Irish church with the papal bull Laudabiliter. However, Henry took no action until 1171. By that time, a number of English nobles, especially the Welsh Marcher Lords, had invaded Ireland and established control over portions of the island. In 1171, Henry landed in Ireland and the Anglo-Norman lords gave him homage and fealty. He also convinced the native Gaelic nobility to become his vassals. In 1185, Henry gave his youngest son, the future King John of England, the title Lord of Ireland.[note 7] John was then sent to Ireland to be crowned as that island's king, but his behavior offended the Irish, who forced John to retreat without being crowned. Thereafter, future English kings used the title Lord of Ireland but mostly ignored the island, preferring to rule through lieutenants for Ireland.[70]

By 1541, King Henry VIII of England had broken with the Church of Rome and declared himself Supreme Head of the Church of England. The Pope's grant of Ireland to the English monarch became invalid, so Henry summoned a meeting of the Irish Parliament to change his title from Lord of Ireland to King of Ireland.[214] In 1800, as a result of the Irish Rebellion of 1798, the Act of Union merged the kingdom of Great Britain and the kingdom of Ireland into the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland.

Union of the Crowns and republican phase

Elizabeth I's death in 1603 ended Tudor rule in England. Since she had no children, she was succeeded by the Scottish monarch James VI, who was the great-grandson of Henry VIII's older sister and hence Elizabeth's first cousin twice removed. James VI ruled in England as James I after what was known as the "Union of the Crowns". Although England and Scotland were in personal union under one monarch – James I & VI became the first monarch to style himself "King of Great Britain" in 1604[215] – they remained two separate kingdoms. James I & VI's successor, Charles I, experienced frequent conflicts with the English Parliament related to the issue of royal and parliamentary powers, especially the power to impose taxes. He provoked opposition by ruling without Parliament from 1629 to 1640, unilaterally levying taxes and adopting controversial religious policies (many of which were offensive to the Scottish Presbyterians and the English Puritans). His attempt to enforce Anglicanism led to organised rebellion in Scotland (the "Bishops' Wars") and ignited the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. In 1642, the conflict between the King and English Parliament reached its climax and the English Civil War began.[216]

The Civil War culminated in the execution of the king in 1649, the overthrow of the English monarchy, and the establishment of the Commonwealth of England. Charles I's son, Charles II, was proclaimed King of Great Britain in Scotland, but he was forced to flee abroad after he invaded England and was defeated at the Battle of Worcester. In 1653, Oliver Cromwell, the most prominent military and political leader in the nation, seized power and declared himself Lord Protector (effectively becoming a military dictator, but refusing the title of king). Cromwell ruled until his death in 1658, when he was succeeded by his son Richard. The new Lord Protector had little interest in governing; he soon resigned.[217] The lack of clear leadership led to civil and military unrest, and to a popular desire to restore the monarchy. In 1660, the monarchy was restored and Charles II returned to Britain.[218]

Charles II's reign was marked by the development of the first modern political parties in England. Charles had no legitimate children, and was due to be succeeded by his Roman Catholic brother, James, Duke of York. A parliamentary effort to exclude James from the line of succession arose; the "Petitioners", who supported exclusion, became the Whig Party, whereas the "Abhorrers", who opposed exclusion, became the Tory Party. The Exclusion Bill failed; on several occasions, Charles II dissolved Parliament because he feared that the bill might pass. After the dissolution of the Parliament of 1681, Charles ruled without a Parliament until his death in 1685. When James succeeded Charles, he pursued a policy of offering religious tolerance to Roman Catholics, thereby drawing the ire of many of his Protestant subjects. Many opposed James's decisions to maintain a large standing army, to appoint Roman Catholics to high political and military offices, and to imprison Church of England clerics who challenged his policies. As a result, a group of Protestants known as the Immortal Seven invited James II & VII's daughter Mary and her husband William III of Orange to depose the king. William obliged, arriving in England on 5 November 1688 to great public support. Faced with the defection of many of his Protestant officials, James fled the realm and William and Mary (rather than James II & VII's Catholic son) were declared joint Sovereigns of England, Scotland and Ireland.[219]

James's overthrow, known as the Glorious Revolution, was one of the most important events in the long evolution of parliamentary power. The Bill of Rights 1689 affirmed parliamentary supremacy, and declared that the English people held certain rights, including the freedom from taxes imposed without parliamentary consent. The Bill of Rights required future monarchs to be Protestants, and provided that, after any children of William and Mary, Mary's sister Anne would inherit the Crown. Mary II died childless in 1694, leaving William III & II as the sole monarch. By 1700, a political crisis arose, as all of Anne's children had died, leaving her as the only individual left in the line of succession. Parliament was afraid that the former James II or his supporters, known as Jacobites, might attempt to reclaim the throne. Parliament passed the Act of Settlement 1701, which excluded James and his Catholic relations from the succession and made William's nearest Protestant relations, the family of Sophia, Electress of Hanover, next in line to the throne after his sister-in-law Anne.[220] Soon after the passage of the Act, William III & II died, leaving the Crown to Anne.

After Anne's accession, the problem of the succession re-emerged. The Scottish Parliament, infuriated that the English Parliament did not consult them on the choice of Sophia's family as the next heirs, passed the Act of Security 1704, threatening to end the personal union between England and Scotland. The Parliament of England retaliated with the Alien Act 1705, threatening to devastate the Scottish economy by restricting trade. The Scottish and English parliaments negotiated the Acts of Union 1707, under which England and Scotland were united into a single Kingdom of Great Britain, with succession under the rules prescribed by the Act of Settlement.[221]

After the 1707 Acts of Union

In 1714, Queen Anne was succeeded by her second cousin, and Sophia's son, George I, Elector of Hanover, who consolidated his position by defeating Jacobite rebellions in 1715 and 1719. The new monarch was less active in government than many of his British predecessors, but retained control over his German kingdoms, with which Britain was now in personal union.[222] Power shifted towards George's ministers, especially to Sir Robert Walpole, who is often considered the first British prime minister, although the title was not then in use.[223] The next monarch, George II, witnessed the final end of the Jacobite threat in 1746, when the Catholic Stuarts were completely defeated. During the long reign of his grandson, George III, Britain's American colonies were lost, the former colonies having formed the United States of America, but British influence elsewhere in the world continued to grow, and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was created by the Acts of Union 1800.[224]

From 1811 to 1820, George III suffered a severe bout of what is now believed to be porphyria, an illness rendering him incapable of ruling. His son, the future George IV, ruled in his stead as Prince Regent. During the Regency and his own reign, the power of the monarchy declined, and by the time of his successor, William IV, the monarch was no longer able to effectively interfere with parliamentary power. In 1834, William dismissed the Whig Prime Minister, William Lamb, 2nd Viscount Melbourne, and appointed a Tory, Sir Robert Peel. In the ensuing elections, however, Peel lost. The king had no choice but to recall Lord Melbourne. During William IV's reign, the Reform Act 1832, which reformed parliamentary representation, was passed. Together with others passed later in the century, the Act led to an expansion of the electoral franchise and the rise of the House of Commons as the most important branch of Parliament.[225]

The final transition to a constitutional monarchy was made during the long reign of William IV's successor, Victoria. As a woman, Victoria could not rule Hanover, which only permitted succession in the male line, so the personal union of the United Kingdom and Hanover came to an end. The Victorian era was marked by great cultural change, technological progress, and the establishment of the United Kingdom as one of the world's foremost powers. In recognition of British rule over India, Victoria was declared Empress of India in 1876. However, her reign was also marked by increased support for the republican movement, due in part to Victoria's permanent mourning and lengthy period of seclusion following the death of her husband in 1861.[226]

Victoria's son, Edward VII, became the first monarch of the House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha in 1901. In 1917, the next monarch, George V, changed "Saxe-Coburg and Gotha" to "Windsor" in response to the anti-German sympathies aroused by the First World War. George V's reign was marked by the separation of Ireland into Northern Ireland, which remained a part of the United Kingdom, and the Irish Free State, an independent nation, in 1922.[227]

Shared monarchy and modern status

During the twentieth century, the Commonwealth of Nations evolved from the British Empire. Prior to 1926, the British Crown reigned over the British Empire collectively; the Dominions and Crown Colonies were subordinate to the United Kingdom. The Balfour Declaration of 1926 gave complete self-government to the Dominions, effectively creating a system whereby a single monarch operated independently in each separate Dominion. The concept was solidified by the Statute of Westminster 1931,[228] which has been likened to "a treaty among the Commonwealth countries".[229]

The monarchy thus ceased to be an exclusively British institution, although it is often still referred to as "British" for legal and historical reasons and for convenience. The monarch became separately monarch of the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and so forth. The independent states within the Commonwealth would share the same monarch in a relationship likened to a personal union.[230][231][232][233]