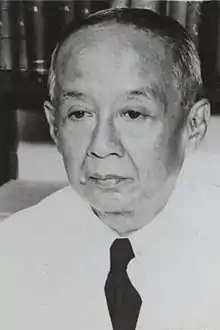

Prof. Dr. Hoesein Djajadiningrat | |

|---|---|

Hoesein Djajadiningrat | |

| Born | 8 December 1886 Kramatwatu, Serang, Dutch East Indies |

| Died | 12 November 1960 (aged 73) Jakarta, Indonesia |

| Nationality | Indonesian |

| Education | Leiden University |

| Spouse | Partini Djajadiningrat |

Husein Jayadiningrat, or Hoesein Djajadiningrat in older spelling (8 December 1886 – 12 November 1960), was an Indonesian scholar in Indonesian studies, Islamic law, and native Indonesian literature. He distinguished himself as one of the first native Indonesian to earn a doctoral degree.[note 1]

Early life

Hoesein, nicknamed 'Ace', was born on 8 December 1886 in Kramatwatu, a subdistrict of Serang, a Regency within the Residency of Banten, Dutch East Indies. His father was Raden Bagoes Djajawinata (1854-1899), the previous Bupati or Regent of Serang. His mother is Ratoe Salehah (1862–1903) of Cipete, Serang.[3]

Hoesein is born fifth in order of nine children; the eldest son Achmad (nicknamed Uyang), Mochammad (Apun), Hasan (Emong), Hoesein (Ace), Chadijah (Enjah), Loekman (Ujang), Soelasmi (Yayung), Hilman (Imang), and Rifqi (Kikok).[3]

Hoesein's family was an aristocratic one, considered part of the priyayi class in Javanese society. His paternal uncle Soetadiningrat and paternal grandfather Natadiningrat was Regent of Pandeglang, another region also in Banten. His elder brother Achmad would succeed their father as regent, initially as Regent of Serang, later transferred to serve as Regent of Batavia.[4]

His brother Achmad first used the name 'Djajadiningrat' as his surname prior from taking final examination for the Hogere Burgerschool in Batavia. Soon after, his siblings, including Hoesein, adopted the surname.[5] His family, the Djajadiningrat family would prove to be an influential family during the Indonesian National Revolution (1945–1949), where various members of the family would play parts on both side of the conflict.

Education

As member of the aristocracy, Hoesein was expected to be educated in western style education after receiving early Islamic religious education, pesantren-style as was common in Banten. Soetadiningrat was particularly enthusiastic in providing education to his family members especially for his nephews and nieces.[5] In late 1880s, the family was introduced to Snouck Hurgronje, an accomplished scholar and advisor for the colonial government of the Dutch East Indies. In 1890 he offered to foster Achmad in providing his education as a future regent. Although smart, he was not as enthusiastic in education as Hoesein, who Hurgronje also offered to foster later.[5]

In 1904 Hoesein graduated from HBS in Serang and promptly sent to the Netherlands to pursue higher education.[2] He went to learn Dutch at Leidsche Gymnasium for a year, then enrolled as a student at Leiden University, attending lectures on ethnography, cultures, and native Indonesian languages. Later in 1907 Hurgronje returned to the Netherlands and gave lecture on Arab cultures; he became Hoesein's education supervisor as well.[3]

He graduated with cum laude, earned his degree on Oriental Studies in 1910, and immediately pursued doctoral degree. Three years later, he would eventually earn his doctoral degree, after defend his dissertation titled "A Critical Study on the History of Banten" (Critische Beschouwing van de Sadjarah Banten), supervised by Hurgronje.[6] His dissertation examination committee, which included Professor Kern, noted that it was well made and critically needed for historical studies of Banten.[7]

Career

After graduating, he first stayed in Aceh in order to study the language, as well as to wrote an Acehnese–Dutch dictionary. The research was conducted from April 1914 to May 1915, and finally published as a two-volume dictionary entitled Atjehsche Nederlandsch Woordenboek, which would be publish years later in 1934.[5][8]

In 1924 he was appointed as a professor at Batavia Law School (Rechtshogeschool te Batavia), giving lectures on Islamic law as well as native Indonesian literatures and languages.[5]

Since 1935 he worked as manuscript conservator at the Royal Batavian Society of Arts and Sciences (Bataviaasch Genootschap van Kunsten en Wetenschappen). Initially served as board member, he would later lead it until 1941. Along with it he also served as member of the Council of the Indies (Raad van Indie, separate body from the Volksraad).

During Japanese occupation of the East Indies (1941–1945), the Japanese authorities appointed him to head the Office of Religious Affairs, replacing the previous officials who left Java alongside the rest of the colonial government to Australia. Alongside them was his younger brother Loekman, who would serve in the Dutch East Indies Government-in-Exile in Australia as commissioner and later head of the education department. He later died in Sydney in 1944.[9] During this time as well, his older brother Achmad died after bout of illness in 1943.[10]

Around this time, he was involved in Indonesian national movement, later became a member for the Investigating Committee for Preparatory Work for Independence (Badan Penyelidik Usaha-usaha Persiapan kemerdekaan) or BPUPK. During the drafting of the would-be Indonesian 1945 Constitution, he served in the Vocabulary Committee (Komisi Penghalus Bahasa), alongside Agus Salim and Soepomo.[11]

For a while after the end of Japanese occupation he joined the Indonesian cabinet, serving as the State Secretary for Education, Culture, and Science in 1948.[8] Later during the Dutch military occupation of west Java during Operation Product, he was asked to serve as chair of the Association of United States of Indonesia Movement, promoting the formation of the United States of Indonesia.[12] His younger brother Hilman, who succeeded Achmad as Regent of Serang in 1935 (later served as well as Japanese-appointed Resident of Banten from 1941 to 1945) became active in West Javan politics, as he led the pro-Dutch, federalist faction in the State of Pasundan. In 1948 Hilman was appointed governor of Djakarta Federal District, serving until 1950.[13]

In 1950 he joined the newly created University of Indonesia as a lecturer in its Faculty of Letters. Two years later, he became a professor of Islamic Studies and Arabic Language. Later in 1957 he became the general director of – and member of the Vocabulary Commission (Komisi Istilah) at – the Language and Culture Office (Lembaga Bahasa dan Budaya) under the Faculty of Letters, serving until his death in 1960. This office would transformed into the Language Development and Fostering Agency (Badan Pengembangan dan Pembinaan Bahasa) currently subordinated under the Indonesian Ministry of Education, Culture, Research, and Technology.[14]

Personal life

_Solo_TMnr_60020668.jpg.webp)

Hoesein proposed to Raden Adjeng Partini in 1920, via his elder brother Achmad.[5] She was the eldest daughter to Prince Prangwedono, later Mangkunegara VII of the royal house of Mangkunegara. Her brother Prince Saroso would one day reigned as Mangkunegara VIII.

Hoesein and Partini married on 9 January 1921, and would had 6 children: Husniah Pardani (b. 15 October 1921), Pardewi Sulwah (b. 9 September 1922), Aminah Patutri (b. 18 May 1924), Ahmad Partomo (b. 10 September 1925), Husein Wahyu (b. 21 April 1928) and Husein Hidayat (b. 21 April 1928), all bore the surname Djajadiningrat.[3][6]

Since 1957 he was troubled by heart disease and hospitalized several times. He died on 12 November 1960 in Jakarta.[5][6]

Awards

On 13 August 2015, President of the Republic of Indonesia Joko Widodo posthumously awarded Hoesein the Bintang Budaya Paramadharma for his service to the state as a pioneer in Indonesian scientific tradition.[15]

Gallery

Family portrait of Hoesein Djajadiningrat, his wife Partini, and their six children.

Family portrait of Hoesein Djajadiningrat, his wife Partini, and their six children._de_vader_van_de_bruid_Solo_TMnr_60020673.jpg.webp) Wedding ceremony of Hoesein and Partini, held in Kraton Mangkunegara.

Wedding ceremony of Hoesein and Partini, held in Kraton Mangkunegara. Hoesein's 70th birthday, surrounded by his wife, children, and grandchildren.

Hoesein's 70th birthday, surrounded by his wife, children, and grandchildren. Hoesein in his student days in Leiden.

Hoesein in his student days in Leiden. Hoesein together with Governor General Alidius Tjarda van Starkenborgh Stachouwer in Buitenzorg (now Bogor).

Hoesein together with Governor General Alidius Tjarda van Starkenborgh Stachouwer in Buitenzorg (now Bogor). Hoesein and Partini attending the funeral service of George V of the United Kingdom, from a church in Batavia.

Hoesein and Partini attending the funeral service of George V of the United Kingdom, from a church in Batavia.

Notes

- ↑ In point of fact, Abdoel Rivai earned his doctoral degree in 1908 in Gent University, Belgium, but through open exam.[1] Hoesein became the first native Indonesian to achieve a doctoral degree via full dissertation in 1913 from Leiden University.[2]

References

- ↑ "Abdul Rivai, Wartawan dan Doktor Bumiputra Pertama". senandika.web.id (in Indonesian). Retrieved 2021-12-13.

- 1 2 RS, Zen. "Si Jenius yang Jadi Bumiputera Pertama Bergelar Doktor". tirto.id (in Indonesian). Retrieved 2021-11-18.

- 1 2 3 4 Djajadiningrat, Achmad (1996). Memoar Pangeran Aria Achmad Djajadiningrat (in Indonesian). Jakarta: Paguyuban Keturunan Achmad Djajadiningrat.

- ↑ Teguh, Irfan. "Achmad Djajadiningrat: Simpati Sang Bupati untuk Kaum Pergerakan". tirto.id (in Indonesian). Retrieved 2021-11-18.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Suryani, Ade Jaya (January–April 2013). "Bantenese Authors and Their Works: A General Overview" (PDF). Alqalam. 30 (1): 184–212.

- 1 2 3 Singgih, Roswita Pamoentjak (1986). Partini: Tulisan Kehidupan Putri Mangkunegaran (Recollections of a Mangkunegaran Princess) (in Indonesian). Jakarta: Djambatan.

- ↑ Poeze, Harry A. (2008). Di Negeri Penjajah: Orang Indonesia di Negeri Belanda 1600-1950 (in Indonesian). Jakarta: Kepustakaan Populer Gramedia. ISBN 978-979-91-0749-7.

- 1 2 Sutanto, Sutopo (1984). Prof. Dr. Hoesein Djajadiningrat: Karya dan Pengabdiannya (in Indonesian). Jakarta: Indonesian Department of Education and Culture.

- ↑ "Matches for R. Loekman "Oedjang" Djajadiningrat". MyHeritage. Retrieved 2021-11-18.

- ↑ Jusuf, Windu. "Kisah Sukses Karir Achmad & Hoesein Djajadiningrat". tirto.id (in Indonesian). Retrieved 2021-11-18.

- ↑ Harbani, Rahma Indina. "Apa Perbedaan Rumusan Dasar Negara dalam Piagam Jakarta dengan Pembukaan UUD 1945?". detikedu (in Indonesian). Retrieved 2022-01-01.

- ↑ Agung, Ide Anak Agung Gde Agung (1995). From the Formation of the State of East Indonesia to the Establishment of the United States of Indonesia. Jakarta: Yayasan Obor Indonesia. p. 348.

- ↑ Kahin, George McT (June 1956). "Representative Government in Southeast Asia. By Rupert Emerson, with Supplementary Chapters by Willard H. Elsbree and Virginia Thompson. (Cambridge: Harvard University Press. 1955. Pp. vii, 197. $3.50.) - The Formation of Federal Indonesia, 1945–1949. By A. Arthur Schiller. (The Hague, Bandung: W. Van Hoeve, Ltd. 1955. Pp. viii, 472.)". American Political Science Review. 50 (2): 505–509. doi:10.2307/1951689. ISSN 1537-5943. JSTOR 1951689.

- ↑ Ministry of Education and Culture. "Sejarah Badan Bahasa".

- ↑ Hutasoit, Moksa. "Jokowi Beri Tanda Kehormatan ke 46 Orang, dari Paloh Sampai Goenawan Mohamad". detiknews (in Indonesian). Retrieved 2021-11-18.