| Part of a series on |

| Astrodynamics |

|---|

In astronautics, the Hohmann transfer orbit (/ˈhoʊmən/) is an orbital maneuver used to transfer a spacecraft between two orbits of different altitudes around a central body. Examples would be used for travel between low Earth orbit and the Moon, or another solar planet or asteroid. In the idealized case, the initial and target orbits are both circular and coplanar. The maneuver is accomplished by placing the craft into an elliptical transfer orbit that is tangential to both the initial and target orbits. The maneuver uses two impulsive engine burns: the first establishes the transfer orbit, and the second adjusts the orbit to match the target.

The Hohmann maneuver often uses the lowest possible amount of impulse (which consumes a proportional amount of delta-v, and hence propellant) to accomplish the transfer, but requires a relatively longer travel time than higher-impulse transfers. In some cases where one orbit is much larger than the other, a bi-elliptic transfer can use even less impulse, at the cost of even greater travel time.

The maneuver was named after Walter Hohmann, the German scientist who published a description of it in his 1925 book Die Erreichbarkeit der Himmelskörper (The Attainability of Celestial Bodies).[1] Hohmann was influenced in part by the German science fiction author Kurd Lasswitz and his 1897 book Two Planets.

When used for traveling between celestial bodies, a Hohmann transfer orbit requires that the starting and destination points be at particular locations in their orbits relative to each other. Space missions using a Hohmann transfer must wait for this required alignment to occur, which opens a launch window. For a mission between Earth and Mars, for example, these launch windows occur every 26 months. A Hohmann transfer orbit also determines a fixed time required to travel between the starting and destination points; for an Earth-Mars journey this travel time is about 9 months. When transfer is performed between orbits close to celestial bodies with significant gravitation, much less delta-v is usually required, as the Oberth effect may be employed for the burns.

They are also often used for these situations, but low-energy transfers which take into account the thrust limitations of real engines, and take advantage of the gravity wells of both planets can be more fuel efficient.[2][3][4]

Example

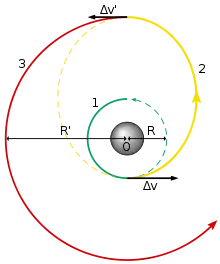

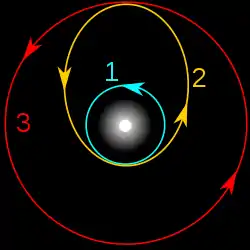

The diagram shows a Hohmann transfer orbit to bring a spacecraft from a lower circular orbit into a higher one. It is an elliptic orbit that is tangential both to the lower circular orbit the spacecraft is to leave (cyan, labeled 1 on diagram) and the higher circular orbit that it is to reach (red, labeled 3 on diagram). The transfer orbit (yellow, labeled 2 on diagram) is initiated by firing the spacecraft's engine to add energy and raise the apogee. When the spacecraft reaches apogee, a second engine firing adds energy to raise the perigee, putting the spacecraft in the larger circular orbit.

Due to the reversibility of orbits, a similar Hohmann transfer orbit can be used to bring a spacecraft from a higher orbit into a lower one; in this case, the spacecraft's engine is fired in the opposite direction to its current path, slowing the spacecraft and lowering its perigee to that of the elliptical transfer orbit. The engine is then fired again at the lower distance to slow the spacecraft into the lower circular orbit. The Hohmann transfer orbit is based on two instantaneous velocity changes. Extra fuel is required to compensate for the fact that the bursts take time; this is minimized by using high-thrust engines to minimize the duration of the bursts. For transfers in Earth orbit, the two burns are labelled the perigee burn and the apogee burn (or apogee kick[5]); more generally, they are labelled periapsis and apoapsis burns. Alternately, the second burn to circularize the orbit may be referred to as a circularization burn.

Type I and Type II

An ideal Hohmann transfer orbit transfers between two circular orbits in the same plane and traverses exactly 180° around the primary. In the real world, the destination orbit may not be circular, and may not be coplanar with the initial orbit. Real world transfer orbits may traverse slightly more, or slightly less, than 180° around the primary. An orbit which traverses less than 180° around the primary is called a "Type I" Hohmann transfer, while an orbit which traverses more than 180° is called a "Type II" Hohmann transfer.[6][7]

Transfer orbits can go more than 360° around the primary. These multiple-revolution transfers are sometimes referred to as Type III and Type IV, where a Type III is a Type I plus 360°, and a Type IV is a Type II plus 360°.[8]

Uses

A Hohmann transfer orbit can be used to transfer an object's orbit toward another object, as long as they co-orbit a more massive body. In the context of Earth and the Solar System, this includes any object which orbits the Sun. An example of where a Hohmann transfer orbit could be used is to bring an asteroid, orbiting the Sun, into contact with the Earth.[9]

Calculation

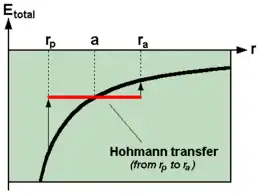

For a small body orbiting another much larger body, such as a satellite orbiting Earth, the total energy of the smaller body is the sum of its kinetic energy and potential energy, and this total energy also equals half the potential at the average distance (the semi-major axis):

Solving this equation for velocity results in the vis-viva equation,

where:

- is the speed of an orbiting body,

- is the standard gravitational parameter of the primary body, assuming is not significantly bigger than (which makes ), (for Earth, this is μ~3.986E14 m3 s−2)

- is the distance of the orbiting body from the primary focus,

- is the semi-major axis of the body's orbit.

Therefore, the delta-v (Δv) required for the Hohmann transfer can be computed as follows, under the assumption of instantaneous impulses:

to enter the elliptical orbit at from the circular orbit, where is the aphelion of the resulting elliptical orbit, and

to leave the elliptical orbit at to the circular orbit, where and are respectively the radii of the departure and arrival circular orbits; the smaller (greater) of and corresponds to the periapsis distance (apoapsis distance) of the Hohmann elliptical transfer orbit. Typically, is given in units of m3/s2, as such be sure to use meters, not kilometers, for and . The total is then:

Whether moving into a higher or lower orbit, by Kepler's third law, the time taken to transfer between the orbits is

(one half of the orbital period for the whole ellipse), where is length of semi-major axis of the Hohmann transfer orbit.

In application to traveling from one celestial body to another it is crucial to start maneuver at the time when the two bodies are properly aligned. Considering the target angular velocity being

angular alignment α (in radians) at the time of start between the source object and the target object shall be

Example

Consider a geostationary transfer orbit, beginning at r1 = 6,678 km (altitude 300 km) and ending in a geostationary orbit with r2 = 42,164 km (altitude 35,786 km).

In the smaller circular orbit the speed is 7.73 km/s; in the larger one, 3.07 km/s. In the elliptical orbit in between the speed varies from 10.15 km/s at the perigee to 1.61 km/s at the apogee.

Therefore the Δv for the first burn is 10.15 − 7.73 = 2.42 km/s, for the second burn 3.07 − 1.61 = 1.46 km/s, and for both together 3.88 km/s.

This is greater than the Δv required for an escape orbit: 10.93 − 7.73 = 3.20 km/s. Applying a Δv at the Low Earth orbit (LEO) of only 0.78 km/s more (3.20−2.42) would give the rocket the escape velocity, which is less than the Δv of 1.46 km/s required to circularize the geosynchronous orbit. This illustrates the Oberth effect that at large speeds the same Δv provides more specific orbital energy, and energy increase is maximized if one spends the Δv as quickly as possible, rather than spending some, being decelerated by gravity, and then spending some more to overcome the deceleration (of course, the objective of a Hohmann transfer orbit is different).

Worst case, maximum delta-v

As the example above demonstrates, the Δv required to perform a Hohmann transfer between two circular orbits is not the greatest when the destination radius is infinite. (Escape speed is √2 times orbital speed, so the Δv required to escape is √2 − 1 (41.4%) of the orbital speed.) The Δv required is greatest (53.0% of smaller orbital speed) when the radius of the larger orbit is 15.5817... times that of the smaller orbit.[10] This number is the positive root of x3 − 15x2 − 9x − 1 = 0, which is . For higher orbit ratios the Δv required for the second burn decreases faster than the first increases.

Application to interplanetary travel

When used to move a spacecraft from orbiting one planet to orbiting another, the situation becomes somewhat more complex, but much less delta-v is required, due to the Oberth effect, than the sum of the delta-v required to escape the first planet plus the delta-v required for a Hohmann transfer to the second planet.

For example, consider a spacecraft travelling from Earth to Mars. At the beginning of its journey, the spacecraft will already have a certain velocity and kinetic energy associated with its orbit around Earth. During the burn the rocket engine applies its delta-v, but the kinetic energy increases as a square law, until it is sufficient to escape the planet's gravitational potential, and then burns more so as to gain enough energy to get into the Hohmann transfer orbit (around the Sun). Because the rocket engine is able to make use of the initial kinetic energy of the propellant, far less delta-v is required over and above that needed to reach escape velocity, and the optimum situation is when the transfer burn is made at minimum altitude (low periapsis) above the planet. The delta-v needed is only 3.6 km/s, only about 0.4 km/s more than needed to escape Earth, even though this results in the spacecraft going 2.9 km/s faster than the Earth as it heads off for Mars (see table below).

At the other end, the spacecraft will need a certain velocity to orbit Mars, which will actually be less than the velocity needed to continue orbiting the Sun in the transfer orbit, let alone attempting to orbit the Sun in a Mars-like orbit. Therefore, the spacecraft will have to decelerate in order for the gravity of Mars to capture it. This capture burn should optimally be done at low altitude to also make best use of the Oberth effect. Therefore, relatively small amounts of thrust at either end of the trip are needed to arrange the transfer compared to the free space situation.

However, with any Hohmann transfer, the alignment of the two planets in their orbits is crucial – the destination planet and the spacecraft must arrive at the same point in their respective orbits around the Sun at the same time. This requirement for alignment gives rise to the concept of launch windows.

The term lunar transfer orbit (LTO) is used for the Moon.

It is possible to apply the formula given above to calculate the Δv in km/s needed to enter a Hohmann transfer orbit to arrive at various destinations from Earth (assuming circular orbits for the planets). In this table, the column labeled "Δv to enter Hohmann orbit from Earth's orbit" gives the change from Earth's velocity to the velocity needed to get on a Hohmann ellipse whose other end will be at the desired distance from the Sun. The column labeled "v exiting LEO" gives the velocity needed (in a non-rotating frame of reference centered on the earth) when 300 km above the Earth's surface. This is obtained by adding to the specific kinetic energy the square of the speed (7.73 km/s) of this low Earth orbit (that is, the depth of Earth's gravity well at this LEO). The column "Δv from LEO" is simply the previous speed minus 7.73 km/s.

| Destination | Orbital radius (AU) |

Δv (km/s) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| to enter Hohmann orbit from Earth's orbit |

exiting LEO |

from LEO | ||

| Sun | 0 | 29.8 | 31.7 | 24.0 |

| Mercury | 0.39 | 7.5 | 13.3 | 5.5 |

| Venus | 0.72 | 2.5 | 11.2 | 3.5 |

| Mars | 1.52 | 2.9 | 11.3 | 3.6 |

| Jupiter | 5.2 | 8.8 | 14.0 | 6.3 |

| Saturn | 9.54 | 10.3 | 15.0 | 7.3 |

| Uranus | 19.19 | 11.3 | 15.7 | 8.0 |

| Neptune | 30.07 | 11.7 | 16.0 | 8.2 |

| Pluto | 39.48 | 11.8 | 16.1 | 8.4 |

| Infinity | ∞ | 12.3 | 16.5 | 8.8 |

Note that in most cases, Δv from LEO is less than the Δv to enter Hohmann orbit from Earth's orbit.

To get to the Sun, it is actually not necessary to use a Δv of 24 km/s. One can use 8.8 km/s to go very far away from the Sun, then use a negligible Δv to bring the angular momentum to zero, and then fall into the Sun. This can be considered a sequence of two Hohmann transfers, one up and one down. Also, the table does not give the values that would apply when using the Moon for a gravity assist. There are also possibilities of using one planet, like Venus which is the easiest to get to, to assist getting to other planets or the Sun.

Comparison to other transfers

Bi-elliptic transfer

The bi-elliptic transfer consists of two half-elliptic orbits. From the initial orbit, a first burn expends delta-v to boost the spacecraft into the first transfer orbit with an apoapsis at some point away from the central body. At this point a second burn sends the spacecraft into the second elliptical orbit with periapsis at the radius of the final desired orbit, where a third burn is performed, injecting the spacecraft into the desired orbit.[11]

While they require one more engine burn than a Hohmann transfer and generally require a greater travel time, some bi-elliptic transfers require a lower amount of total delta-v than a Hohmann transfer when the ratio of final to initial semi-major axis is 11.94 or greater, depending on the intermediate semi-major axis chosen.[12]

The idea of the bi-elliptical transfer trajectory was first published by Ary Sternfeld in 1934.[13]

Low-thrust transfer

Low-thrust engines can perform an approximation of a Hohmann transfer orbit, by creating a gradual enlargement of the initial circular orbit through carefully timed engine firings. This requires a change in velocity (delta-v) that is greater than the two-impulse transfer orbit[14] and takes longer to complete.

Engines such as ion thrusters are more difficult to analyze with the delta-v model. These engines offer a very low thrust and at the same time, much higher delta-v budget, much higher specific impulse, lower mass of fuel and engine. A 2-burn Hohmann transfer maneuver would be impractical with such a low thrust; the maneuver mainly optimizes the use of fuel, but in this situation there is relatively plenty of it.

If only low-thrust maneuvers are planned on a mission, then continuously firing a low-thrust, but very high-efficiency engine might generate a higher delta-v and at the same time use less propellant than a conventional chemical rocket engine.

Going from one circular orbit to another by gradually changing the radius simply requires the same delta-v as the difference between the two speeds.[14] Such maneuver requires more delta-v than a 2-burn Hohmann transfer maneuver, but does so with continuous low thrust rather than the short applications of high thrust.

The amount of propellant mass used measures the efficiency of the maneuver plus the hardware employed for it. The total delta-v used measures the efficiency of the maneuver only. For electric propulsion systems, which tend to be low-thrust, the high efficiency of the propulsive system usually compensates for the higher delta-V compared to the more efficient Hohmann maneuver.

Transfer orbits using electrical propulsion or low-thrust engines optimize the transfer time to reach the final orbit and not the delta-v as in the Hohmann transfer orbit. For geostationary orbit, the initial orbit is set to be supersynchronous and by thrusting continuously in the direction of the velocity at apogee, the transfer orbit transforms to a circular geosynchronous one. This method however takes much longer to achieve due to the low thrust injected into the orbit.[15]

Interplanetary Transport Network

In 1997, a set of orbits known as the Interplanetary Transport Network (ITN) was published, providing even lower propulsive delta-v (though much slower and longer) paths between different orbits than Hohmann transfer orbits.[16] The Interplanetary Transport Network is different in nature than Hohmann transfers because Hohmann transfers assume only one large body whereas the Interplanetary Transport Network does not. The Interplanetary Transport Network is able to achieve the use of less propulsive delta-v by employing gravity assist from the planets.

See also

Citations

- ↑ Walter Hohmann, The Attainability of Heavenly Bodies (Washington: NASA Technical Translation F-44, 1960) Internet Archive.

- ↑ Williams, Matt (2014-12-26). "Making the Trip to Mars Cheaper and Easier: The Case for Ballistic Capture". Universe Today. Retrieved 2019-07-29.

- ↑ Hadhazy, Adam. "A New Way to Reach Mars Safely, Anytime and on the Cheap". Scientific American. Retrieved 2019-07-29.

- ↑ "An Introduction to Beresheet and Its Trajectory to the Moon". Gereshes. 2019-04-08. Retrieved 2019-07-29.

- ↑ Jonathan McDowell, "Kick In the Apogee: 40 years of upper stage applications for solid rocket motors, 1957-1997", 33rd AIAA Joint Propulsion Conference, July 4, 1997. abstract. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- ↑ NASA, Basics of Space Flight, Section 1, Chapter 4, "Trajectories". Retrieved 26 July 2017. Also available spaceodyssey.dmns.org.

- ↑ Tyson Sparks, Trajectories to Mars Archived 2017-10-28 at the Wayback Machine, Colorado Center for Astrodynamics Research, 12/14/2012. Retrieved 25 July 2017.

- ↑ Langevin, Y. (2005). "Design issues for Space Science Missions," Payload and Mission Definition in Space Sciences, V. Mártínez Pillet, A. Aparicio, and F. Sánchez, eds., Cambridge University Press, p. 30. ISBN 052185802X, 9780521858021

- ↑ Calla, Pablo; Fries, Dan; Welch, Chris (2018). "Asteroid mining with small spacecraft and its economic feasibility". arXiv:1808.05099 [astro-ph.IM].

- ↑ Vallado, David Anthony (2001). Fundamentals of Astrodynamics and Applications. Springer. p. 317. ISBN 0-7923-6903-3.

- ↑ Curtis, Howard (2005). Orbital Mechanics for Engineering Students. Elsevier. p. 264. ISBN 0-7506-6169-0.

- ↑ Vallado, David Anthony (2001). Fundamentals of Astrodynamics and Applications. Springer. p. 318. ISBN 0-7923-6903-3.

- ↑ Sternfeld, Ary J. (1934-02-12), "Sur les trajectoires permettant d'approcher d'un corps attractif central à partir d'une orbite keplérienne donnée" [On the allowed trajectories for approaching a central attractive body from a given Keplerian orbit], Comptes rendus de l'Académie des sciences (in French), Paris, 198 (1): 711–713.

- 1 2 MIT, 16.522: Space Propulsion, Session 6, "Analytical Approximations for Low Thrust Maneuvers", Spring 2015 (retrieved 26 July 2017)

- ↑ Spitzer, Arnon (1997). Optimal Transfer Orbit Trajectory using Electric Propulsion. USPTO.

- ↑ Lo, M. W.; Ross, S. D. (1997). "Surfing the Solar System: Invariant Manifolds and the Dynamics of the Solar System". Technical Report. IOM. JPL. pp. 2–4. 312/97.

General and cited sources

- Bate, R. R.; Mueller, D.D.; White, J.E. (1971). Fundamentals of Astrodynamics. New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-60061-1.

- Battin, R .H. (1999). An Introduction to the Mathematics and Methods of Astrodynamics. Washington, DC: American Institute of Aeronautics & Ast. ISBN 978-1-56347-342-5.

- Hohmann, Walter (1925). Die Erreichbarkeit der Himmelskörper. Munich: R. Oldenbourg Verlag. ISBN 3-486-23106-5.

- Thornton, Stephen T.; Marion, Jerry B. (2003). Classical Dynamics of Particles and Systems (5th ed.). Brooks Cole. ISBN 0-534-40896-6.

- Vallado, D. A. (2001). Fundamentals of Astrodynamics and Applications (2nd ed.). Springer. ISBN 978-0-7923-6903-5.

Further reading

- "Orbital Mechanics". Rocket and Space Technology. Robert A. Braeunig. Archived from the original on 2012-02-04. Retrieved 2005-08-17.

- "4. Interplanetary Trajectories". Basics of Spaceflight. JPL: NASA.