| Battle of Posada | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Hungarian-Wallachian Wars | |||||||

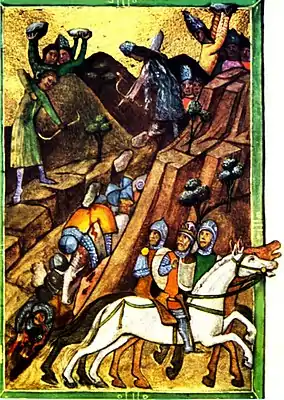

Dezső sacrifices himself protecting Charles Robert, by József Molnár, oil on canvas in 1855 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Kingdom of Hungary | Wallachia | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Charles I Robert Stephen I Lackfi Thomas Szécsényi | Basarab I | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 30,000[2] | 7,000–10,000[2] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Very heavy[2] | Light[2] | ||||||

Location within Romania | |||||||

The Battle of Posada (9–12 November 1330)[3] was fought between Basarab I of Wallachia and Charles I of Hungary (also known as Charles Robert).

The small Wallachian army led by Basarab, formed of cavalry and foot archers, as well as local peasants, managed to ambush and defeat the 30,000-strong Hungarian army, in a mountainous region.

The battle resulted in a major Wallachian victory. Sălăgean writes that the victory "sanctioned the independence of Wallachia from the Hungarian crown" and altered its international status.[4] Georgescu describes Wallachia as the "first independent Romanian principality."[5] Although the kings of Hungary continued to demand loyalty from the voivodes of Wallachia, Basarab and his successors yielded to them only temporarily in the 14th century.[6]

Background

Some historians claim that the Cumans aided the Wallachians in the battle. Still in the Hungarian army there was a substantial Cuman-Hungarian contingent so this variant is very improbable. In 1324, Wallachia was a vassal of Hungary, and Charles referred to Basarab as "our Transalpine Voivode".[7]

The war started with encouragement from the Voivode of Transylvania[8] and a certain Dionisie, who later bore the title Ban of Severin.[7] In 1330, Charles captured the long disputed Wallachian citadel of Severin and handed it to the Transylvanian Voivode.[8]

Basarab sent envoys who asked for the hostilities to cease, and in return offered to pay 7,000 marks in silver, submit the fortress of Severin to Charles, and send his own son as hostage.[8] According to the Viennese Illuminated Chronicle, a contemporary account, Charles said about Basarab: "He is the shepherd of my sheep, and I will take him out of his mountains, dragging him by his beard." Another account writes that Charles said that: "...he will drag the Voivode from his cottage, as would any driver his oxen or shepherd his sheep".[8]

The King's councillors begged him to accept the offer or give a milder reply, but he refused and led his 30,000-strong army deeper into Wallachia "without proper supplies or adequate reconnaissance".[8]

Charles entered Curtea de Argeș, the main city of the Wallachian state. Basarab having fled into the mountains, Charles decided to give chase. After many days of difficult marching in the Carpathian Mountains, the king and Basarab agreed to an armistice, with the condition that the latter would provide guides who knew the way out of the mountains and would lead the army back to the Hungarian plain by the shortest route.[8]

When the army entered a ravine, the Wallachians started to attack them from all sides, shooting arrows and pelting them with trees and stones.[8][9] The army of Charles Robert was however decisively defeated following heavy hand to hand combat during the last two days of the battle.[10]

Battle

.jpg.webp)

The location of the battle is still debated among historians. One theory gives the location of the battle at Loviștea, in some mountain gorges, in the Olt Defile, Transylvania.[7] However, Romanian historian Neagu Djuvara denies this and states that the location of the battle was somewhere at the border between Oltenia and Severin.[11]

The Hungarian royal army was made up of ecclesiastics and laymen with military duties. They were joined by Székelys and the Transylvanian Saxons (except the Saxons of Sibiu, who supported Basarab and refused to join Charles' army), as well as numerous units of mercenaries and "countless numbers of Cumans". Stephen Lackfi was named the commander of the army.[12]

The Wallachian army, led by Basarab himself, probably numbered less than 10,000 men and consisted of cavalry, infantry, archers, and some locally recruited peasants.[9] When Charles saw his best knights being killed, without being able to fight back, while the escape routes were blocked by the Wallachian cavalry, he gave his royal robes and insignia to one Desev, son of Dionysius [13] – "who dies under a hail of arrows and stones" – and, with a few loyal subjects, made a difficult escape to Visegrád "clad in dirty civilian clothes".[8]

Charles later recounted in detail, in a charter of 13 December 1335, how one "Nicholas, son of Radoslav", saved his life by defending him from the swords of five Wallachian warriors, giving him enough time to escape.[7]

Aftermath

The Vlachs carried many away captive, both wounded and uninjured, and from the bodies of the fallen they took many weapons and much precious raiment, money in silver and gold, costly vessels and baldrics, many purses heavy with coins, and many horses with saddles and bridles, all which they carried away and gave to the Voivode Basarab.

The victory represented the survival of the Wallachian state, as well as the beginning of a period of tense relations between Basarab and the Kingdom of Hungary, which lasted until 1344, when Basarab sent his son Alexandru in order to re-establish a relationship between the two states.[15]

Because of its large financial power, the Kingdom of Hungary quickly rebuilt its army and found itself in conflict with the Holy Roman Empire in 1337. However, the Hungarian king maintained a de jure suzerainty over Wallachia until the diplomatic disputes had been resolved.[15]

See also

Footnotes

- ↑ Djuvara, pp. 190 – "Când ultimii scăpați teferi din marea oaste a lui Carol cel Mare s-au pierdut în noapte, au rămas in mâinile românilor o mulțime de prizonieri și o uriașă pradă...".

- 1 2 3 4 Djuvara, pp. 172–180

- ↑ Djuvara, pp. 19– "... marea bătălie zisă de la Posada (9–12 noiembrie 1330)".

- ↑ Sălăgean 2005, p. 195.

- ↑ Georgescu 1991, p. 17.

- ↑ Vásáry 2005, p. 155.

- 1 2 3 4 Ghyka, p. 59.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Dlugosz, p. 278.

- 1 2 Djuvara, pp. 184–186 – "Ne putem închipui manevra lui Basarab: văzând calea pe care a apucat armata ungară, a depășit-o în marș forțat cu oastea sa de cavaleri și cu pedestrime de arcași din oastea mare. A strâns din țăranii și pădurarii locului de au pregătit acele prisăci, tăieri de copaci și întărituri. Cei care, de pe dealurile înconjurătoare, îi copleșesc sub ploaie de săgeți pe cavaleri sunt mai probabil unități de arcași pedeștrii."

- ↑ Rezachevici 2004, p. 169.

- ↑ Djuvara, pp. 181–182 – "...atacul lui Basarab împotriva armatei ungare are loc când aceasta a ajuns la acele margini ale regatului pe care Basarab, în concepția suzeranului Carol Robert, le deținea pe nedrept – acelea nu puteau fi decât la granița Olteniei, inăuntrul banatului de Severin, ...".

- ↑ Rezachevici 2004, p. 170.

- ↑ Rezachevici 2004, p. 174.

- ↑ János M. Bak; László Veszprémy (2018). The Illuminated Chronicle: Chronicle of the Deeds of the Hungarians from the Fourteenth-Century Illuminated Codex. Central European University Press. ISBN 978-963-386-264-3.

- 1 2 Djuvara, pp. 190–195 – "...Basarab l-ar fi trimis prin 1343 sau 1344, pe fiul său Alexandru, asociat la domnie, pentru a restabili legăturile cu regele Ungariei, ...".

References

- Długosz, Jan & Michael, Maurice. The Annals of Jan Długosz. (Abridged edition). IM Publications, 1997. ISBN 1-901019-00-4

- Georgescu, Vlad (1991). The Romanians: A History. Ohio State University Press. ISBN 0-8142-0511-9.

- Ghyka, Matila. A Documented Chronology of Roumanian History – from prehistoric times to the present day. Oxford 1941.

- Djuvara, Neagu. Thocomerius – Negru Vodă. Un voivod de origine cumană la inceputurile Țării Românești. Bucharest: Humanitas, 2007. ISBN 978-973-50-1731-6.

- Rezachevici, Constantin (2004). "Caracterul bătăliei din 1330 între Basarab și Carol Robert: Țărani neînarmați sau cavaleri de tip apusean?". Argesis – Studii și Comunicări [The character of the 1330 battle between Basarab and Carol Robert: Unarmed peasants or Western-style knights?]. Pitești: Muzeul Județean Argeș.

- Sălăgean, Tudor (2005). "Romanian Society in the Early Middle Ages (9th–14th Centuries AD)". In Pop, Ioan-Aurel; Bolovan, Ioan (eds.). History of Romania: Compendium. Romanian Cultural Institute (Center for Transylvanian Studies). pp. 133–207. ISBN 978-973-7784-12-4.

- Vásáry, István (2005). Cumans and Tatars: Oriental Military in the Pre-Ottoman Balkans, 1185–1365. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-83756-1.