| 1906 Atlantic hurricane season | |

|---|---|

Season summary map | |

| Seasonal boundaries | |

| First system formed | June 8, 1906 |

| Last system dissipated | November 9, 1906 |

| Strongest storm | |

| Name | Four |

| • Maximum winds | 130 mph (215 km/h) (1-minute sustained) |

| • Lowest pressure | 950 mbar (hPa; 28.05 inHg) |

| Seasonal statistics | |

| Total depressions | 12 |

| Total storms | 11 |

| Hurricanes | 6 |

| Major hurricanes (Cat. 3+) | 3 |

| Total fatalities | At least 381 |

| Total damage | > $25.372 million (1906 USD) |

| Related articles | |

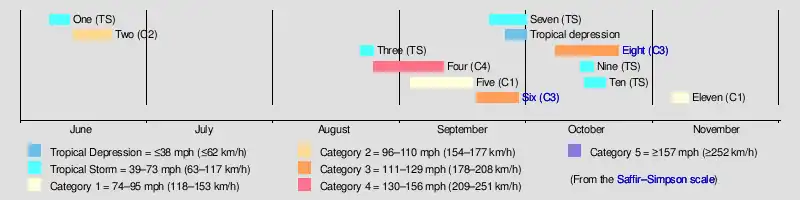

The 1906 Atlantic hurricane season was an average season. It featured twelve tropical cyclones, eleven of which became storms, six became hurricanes and three became major hurricanes. The first storm of the season, a tropical storm in the northern Caribbean, formed on June 8; although it struck the United States, no major impacts were recorded. July saw a period of inactivity, with no known storms. However, in August, the streak of inactivity ended with two storms, including a powerful hurricane. September brought three storms, including a deadly hurricane, with catastrophic impacts in Pensacola and Mobile. October included three storms, with a powerful hurricane that killed over 200 people. The final storm of the season impacted Cuba in early November and dissipated on November 9. The season was quite deadly, with at least with 381 total recorded deaths.[note 1]

Season summary

Prior to the advent of modern tropical cyclone tracking technology, notably satellite imagery, many hurricanes that did not affect land directly went unnoticed, and storms that did affect land were not recognized until their onslaught. As a result, information on older hurricane seasons was often incomplete. Modern-day efforts have been made and are still ongoing to reconstruct the tracks of known hurricanes and to identify initially undetected storms. In many cases, the only evidence that a hurricane existed was reports from ships in its path, and judging by the direction of winds experienced by ships, and their location in relation to the storm, it is possible to roughly pinpoint the storm's center of circulation for a given point in time. This is the manner in which all of the eleven known storms in the 1906 season were identified by hurricane expert José Fernández-Partagás's reanalysis of hurricane seasons between 1851 and 1910. Partagás also extended the known tracks of three other hurricanes previously identified by scholars. The information Partagás and his colleague uncovered was largely adopted by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Atlantic hurricane reanalysis in their updates to the Atlantic hurricane database (HURDAT), with some slight adjustments. HURDAT is the official source for such hurricane data as track and intensity, although due to a sparsity of available records at the time the storms existed, listings on some storms are incomplete.[2][3]

The season's activity was reflected with an accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) rating of 163, the highest total since 1893. ACE is a metric used to express the energy used by a tropical cyclone during its lifetime. Therefore, a storm with a longer duration will have high values of ACE. It is only calculated at six-hour increments in which specific tropical and subtropical systems are either at or above sustained wind speeds of 39 mph (63 km/h), which is the threshold for tropical storm intensity. Thus, tropical depressions are not included here.[4]

Systems

Tropical Storm One

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | June 8 – June 13 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min); <1002 mbar (hPa) |

The first storm of the season formed on June 8, south of western Cuba, attaining its peak winds of 50 mph (80 km/h) by June 9.[2] On June 10, a weather station in Havana reported a minimum air pressure of 1002 mbar (hPa; 29.59 inHg);[5] however, the minimum pressure of the system itself is unknown.[2] On June 12, the system caused the sinking of a schooner; however, all on board the schooner were rescued.[5] The system continued traveling north-northwestward, making landfall near Panama City on June 13, quickly weakening to a tropical depression as it moved inland. The system became extratropical by June 14, dissipating shortly thereafter;[2] no deaths and injuries are known to have been caused by the storm.

Hurricane Two

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | June 14 – June 23 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 105 mph (165 km/h) (1-min); 979 mbar (hPa) |

This first hurricane of the season's effects were first noted in Santa Clara, Cuba, where rainy and windy conditions were observed on the afternoon of June 14. Several vessels sank during the hurricane during the early morning hours of June 15. The system was thought to have entered the Florida Straits during the evening.[5] The system began to travel towards the west-northwest, steadily strengthening into a hurricane by the afternoon. On June 17, a minimum pressure of 979 mbar (hPa; 28.91 inHg) was recorded, as the hurricane passed over southern Florida.[2]

The hurricane slowly intensified as it traveled offshore, continuing to strengthen throughout the day on June 17, eventually reaching Category 2 status by June 18. As the storm headed northeastward, the hurricane began to weaken, becoming a tropical storm by June 21. The system turned toward the east-southeast on June 21, later recurving towards the east-northeast on June 22. It weakened to a tropical depression by June 23, transitioning into an extratropical cyclone later that day.[2] Impacts caused by the hurricane were minimal—a boat was partially dismantled at Key West, and a wharf at Coconut Grove was also damaged. In addition, the schooner Hidie Feroe sank, although her crew was later rescued.[5]

Tropical Storm Three

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 22 – August 25 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 70 mph (110 km/h) (1-min); <1003 mbar (hPa) |

This tropical storm was previously unidentified until modern research by José Fernández-Partagás revealed the storm in 1997.[5] The tropical storm is believed to have originated as a tropical depression in the North Atlantic on August 22. By August 23, the depression had intensified into a tropical storm, with winds of 40 mph (65 km/h). The system further intensified into a powerful tropical storm on August 24, with winds of 70 mph (115 km/h). However, the storm began to weaken, and it transitioned into an extratropical storm on August 25, with winds of 60 mph (95 km/h).[2]

Hurricane Four

| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 25 – September 11 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 130 mph (215 km/h) (1-min); 950 mbar (hPa) |

The fourth storm of the season was believed to have originated as a tropical storm off the coast of Africa on August 25. The storm slowly intensified, eventually reaching hurricane status on August 28. As the storm headed west-northwestward on August 31, it passed by the Lesser Antilles as a Category 2 hurricane. The storm became a Category 3 hurricane on September 2 as it passed north of the Dominican Republic. The storm further intensified into a Category 4 hurricane on September 5, located east of the Bahamas. Throughout the day on September 6, the hurricane began to curve northward. During the evening, it weakened to Category 3 status and began to travel northeastward on September 7.[2]

The hurricane maintained its intensity and passed northwest of Bermuda on September 9, where winds reached 70 mph (115 km/h) and air pressures fell to 988 mbar (hPa; 29.18 inHg). The storm continued to weaken, eventually becoming a Category 2 hurricane on September 11;[2] at this time, the Koenigin Luise measured an air pressure of 950 mbar (hPa; 28.06 inHg).[6] The system became extratropical later during the day, and lost its identity on September 12 in the North Atlantic near the British Isles.[2] As a result of warnings in advance, little damage was caused by the hurricane.[6]

Hurricane Five

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 3 – September 18 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 90 mph (150 km/h) (1-min); 977 mbar (hPa) |

The fifth storm of the season formed on September 3 in the western Atlantic. It drifted west-northwestward, slowly gaining intensity, and turned northwest on September 8. However, the tropical storm then changed course and began to head west-northwest on September 11 as it slowly intensified. By September 12, the tropical storm had intensified to a minimal hurricane, and began to turn towards the north-northwest on September 13. It attained its peak winds of 90 mph (145 km/h) on September 14. As it maintained its intensity on September 15, the hurricane began to turn westward while it continued to approach the coast of South Carolina on September 17. The hurricane made landfall near Myrtle Beach later on September 17, and quickly weakened to a tropical storm as it moved inland. The storm dissipated as a tropical depression on September 18 over Tennessee.[2]

The hurricane caused moderate impacts — two hundred people were stranded at Wrightsville Beach, North Carolina.[7] At Charleston, South Carolina, winds of 46 mph (74 km/h) were recorded, in addition to a barometric pressure of 997 mbar (hPa; 29.44 inHg).[5] Many small buildings were damaged in Charleston; damage in the city totaled to $1,000, while at the town of Georgetown, damage was estimated to be around $15,000.[6] The Laura encountered the hurricane, and three of the crew of four were killed.[8] A schooner called the Seguranca and its crew were also impacted by the hurricane; the crew on board survived without food for two days.[9] Overall damage to shipping and crops in the Carolinas was moderate;[5] seven people were killed, and at least $2,016,000 (1906 USD) in damage was recorded.[10]

Hurricane Six

| Category 3 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 19 – September 29 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 120 mph (195 km/h) (1-min); 953 mbar (hPa) |

The Mississippi Hurricane of 1906

The sixth hurricane of the season originated as a tropical depression on September 19 in the southwestern Caribbean Sea. The following day, the depression intensified into a tropical storm. It continued to intensify steadily, eventually reaching hurricane status on September 24 as it exited the Yucatán Channel. The hurricane continued to intensify as it moved north-northwest and attained Category 2 intensity in the Gulf of Mexico. During the afternoon, the storm intensified further into a major hurricane.[2] At this time, the hurricane was 300 miles (485 km) west-northwest of Cuba.[5] The hurricane maintained intensity and continued to drift north-northwest,[2] and weakened to a Category 2 hurricane as it made landfall near Pascagoula, Mississippi, on September 27.[6] The hurricane weakened as it moved inland, quickly weakening to a tropical storm by September 28. The storm became extratropical on September 29.[2]

The hurricane caused severe damage along the Gulf Coast. Many marine vessels were blown ashore or sunken in Pensacola,[6] and railroads in the city were severely damaged.[11][12] Numerous wharfs were damaged or destroyed, and many roofs were torn off buildings. Three forts in the vicinity of Pensacola suffered damage.[6] Electricity in the city was shut off.[11] A total of 25 people were killed in Pensacola.[13] Mobile and surrounding areas suffered similar damage, including destroyed timber,[6] smashed windows, and sunken watercraft.[14] In Mississippi, over 300,000 cotton bales were ruined during the hurricane, amounting to $12,000,000 in damage.[12] Damage in New Orleans was minimal; however, Lake Pontchartrain overflowed, flooding the city.[11] The hurricane killed a total of 134 people.[1]

Tropical Storm Seven

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 22 – October 1 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 70 mph (110 km/h) (1-min); <994 mbar (hPa) |

This tropical storm was previously unidentified and was not considered a tropical storm until research by José Fernández-Partagás in 1997.[15] The storm is believed to have originated west of the Canary Islands in the northeastern Atlantic on September 22. The tropical storm moved west-southwestward for several days, maintaining its peak winds of 70 mph (115 km/h); however, the storm began to curve early on September 26 and traveled directly westward before curving northward during the afternoon. The tropical storm continued to change course, turning west-northwestward by September 28. The transitioned to an extratropical system on October 1,[2] and reached England on October 3.[15]

Tropical depression

A tropical depression developed over the eastern Caribbean on September 26. The depression moved generally westward and likely peaked with maximum sustained winds of 35 mph (55 km/h). By September 30, the depression curved west-northwestward and dissipated near Cuba's Cabo San Antonio on the following day.[3]

Hurricane Eight

| Category 3 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 8 – October 23 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 120 mph (195 km/h) (1-min); 953 mbar (hPa) |

The Florida Keys and Miami Hurricane of 1906

This hurricane originated on October 4 near Barbados as a "cyclonic perturbation"; however, no closed circulation was evidently associated with the system. Barometric pressures began sinking in Panama as the system drifted westward,[15] and it was considered a tropical storm by October 8. As the storm headed west, it rapidly strengthened; the storm became a hurricane on October 9 and intensified into a major hurricane on October 10. As it began to curve northwestward, the hurricane made landfall in Nicaragua, and weakened to a tropical storm on October 11. It began to drift north-northwestward later that day, intensifying into a minimal hurricane as it drifted into the Gulf of Honduras.[2]

However, the hurricane weakened to a tropical storm again on October 14 as it moved overland, and began to curve north-northwest, restrengthening to a major hurricane by October 17 while it was west-southwest of Cuba. The hurricane made landfall over Cuba on the evening of October 17. The hurricane passed over southern Florida near Pigeon Key and Downtown Miami on October 18. The hurricane continued traveling north-northwest; however, it was forced to re-curve south-southwest,[2] as a result of a high-pressure area.[6] The hurricane weakened to a tropical storm overland, eventually becoming a tropical depression. The system meandered into the Gulf of Mexico, making a final landfall in Central America on October 23.[2]

The hurricane wreaked havoc throughout its path — crops in Central America suffered severe damage, and rainfall destroyed many roads and bridges in Nicaragua.[6] In Cuba, at least 29 people were killed,[16][17] and tobacco crops in the country were ruined.[18] The most severe damage was caused in Florida — the state suffered more than $420,000 in damage and more than two hundred people were killed. Of the people killed in Florida, 135 were workers on the Florida East Coast Railway,[6] and more than 70 people were drowned near Elliott Key after two steamers sank.[19] Throughout its path, damage caused by the hurricane totaled to at least $4,135,000 and at least 240 deaths were recorded.[note 2]

Tropical Storm Nine

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 14 – October 17 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min); <1003 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical storm was believed to have formed from a low-pressure area, possibly on the tail end of a cold front on October 14.[15] The storm moved westward; however, it began to curve west-southwestward on October 15, as it reached its peak winds of 50 mph (80 km/h). The storm continued to trek towards the west-southwest on October 16, later making landfall in eastern Florida on October 17 as a tropical depression.[2] No damage is known to have been caused by the tropical storm.

Tropical Storm Ten

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 15 – October 20 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min); <1005 mbar (hPa) |

The tenth storm of the season formed on October 15 as a tropical storm east of the Bahamas and north of Hispaniola. The tropical storm moved northwest, but changed direction and began to curve northeastward on October 17. As the storm moved eastward, it slowly strengthened; the storm attained its peak winds of 50 mph (80 km/h) on October 18. The tropical storm headed directly eastward on October 19, and dissipated in the open Atlantic on October 20.[2]

Hurricane Eleven

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | November 5 – November 9 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 80 mph (130 km/h) (1-min); <997 mbar (hPa) |

The final storm of the season started as a tropical depression on November 5, located in the Caribbean, south of Cuba. It strengthened into a tropical storm later during the day as it curved northward, and the storm turned towards the northeast on November 6. As it approached Cuba, the storm briefly attained hurricane status; however, as the hurricane made landfall over Cuba, it weakened to a tropical storm. The storm drifted over the Bahamas as a minimal tropical storm on November 8 while it traced east-northeast. It continued to weaken, and transitioned into an extratropical storm on November 10.[2] No damage is known to have been caused by the hurricane. Its path, its intensity, and the time of the year in which it formed are very similar to those of Hurricane Katrina of 1981.

See also

Notes

Footnotes

- ↑ Data for fatalities caused by hurricanes Five and Eight are not taken from National Hurricane Center data; however, the total number of deaths, 381, maintains the position of eleventh-deadliest season.[1]

- ↑ For information on individual deaths and damage, see notes on the 1906 Florida Keys hurricane.

Citations

- 1 2 Blake, Eric; Gibney, Ethan (August 2011). "The deadliest, costliest, and most intense United States tropical cyclones from 1851 to 2010" (PDF). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2011-10-23.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 "Easy to Read HURDAT 2011". HURDAT Re-Analysis Project. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 2011. Retrieved 2011-10-15.

- 1 2 Hurricane Research Division (2011). "Documentation of Atlantic Tropical Cyclones Changes in HURDAT". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on 4 June 2011. Retrieved 2011-06-04.

- ↑ Atlantic Basin Comparison of Original and Revised HURDAT. Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. September 2021. Retrieved October 1, 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Fernández-Partagás, José; Diaz, Henry F. (1997). A Reconstruction of Historical Tropical Cyclone Frequency in the Atlantic from Documentary and other Historical Sources (part 1) (PDF). Boulder, Colorado: Climate Diagnostics Center, NOAA. Retrieved 2011-10-14.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 "Monthly Weather Review" (PDF). American Meteorological Society. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 1906. pp. 479–480. Retrieved 2011-10-21.

- ↑ "Cut Off by 70-Mile Gale". The New York Times. 1906-09-18. p. 1. Retrieved 2021-08-27 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Sick Mate Saves a Ship". The New York Times. 1906-09-20. p. 1. Retrieved 2021-08-27 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Saved Starving Crew from Ship's Rigging". The New York Times. 1906-09-23. p. 22. Retrieved 2021-08-27 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Longshore, David (2008). Encyclopedia of hurricanes, typhoons, and cyclones. Facts on File, Inc. ISBN 978-0-8160-6295-9. Retrieved 2011-10-25.

- 1 2 3 "Storm Churns Gulf". Youngstown Vindicator. 1906-09-28. p. 20. Retrieved 2021-08-27.

- 1 2 "Death and Ruin in Path of Hurricane". The Pittsburgh Press. 1906-09-28. p. 1. Retrieved 2021-08-27.

- ↑ "25 Dead at Pensacola". The Baltimore Sun. 1906-09-30. p. 5. Retrieved 2021-08-27 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Armed Men to Save Water-Soaked City". The Philadelphia Record. 1906-09-29.

- 1 2 3 4 Fernández-Partagás, José; Diaz, Henry F. (1997). A Reconstruction of Historical Tropical Cyclone Frequency in the Atlantic from Documentary and other Historical Sources (part 2) (PDF). Boulder, Colorado: Climate Diagnostics Center, NOAA. Retrieved 2011-10-23.

- ↑ "Twenty Dead in Havana". The New York Times. 1906-10-20. p. 1. Retrieved 2021-08-27 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Hundreds of Persons Homeless and Destitute; Crops are Ruined". Havana, Cuba: The St. John Sun. 1906-10-20. Retrieved 2011-10-23.

- ↑ "Story of the Storm". Lewiston Evening Journal. 1906-10-20. Retrieved 2011-10-23.

- ↑ Plumbe, George Edward; Langland, James; Pike, Claude Othello (1907). The Chicago daily news almanac and year book for 1907. Vol. 23. Retrieved 2011-10-23.