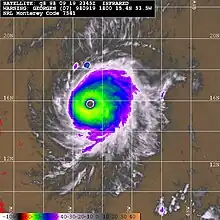

Georges near peak intensity east of the Leeward Islands on September 19 | |

| Meteorological history | |

|---|---|

| Formed | September 15, 1998 |

| Dissipated | October 1, 1998 |

| Category 4 hurricane | |

| 1-minute sustained (SSHWS/NWS) | |

| Highest winds | 155 mph (250 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 937 mbar (hPa); 27.67 inHg |

| Overall effects | |

| Fatalities | 604 |

| Damage | $9.37 billion (1998 USD) (Costliest in Dominican Republic history) |

| Areas affected | Leeward Islands, Puerto Rico, Hispaniola, Cuba, Florida Keys, Southeastern Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Florida, Georgia |

| IBTrACS | |

Part of the 1998 Atlantic hurricane season | |

| History

Effects

Other wikis | |

Hurricane Georges (/ʒɔːrʒ/) was a powerful and long-lived Cape Verde Category 4 hurricane which caused severe destruction as it traversed the Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico in September 1998, making seven landfalls along its path. Georges was the seventh tropical storm, fourth hurricane, and second major hurricane of the 1998 Atlantic hurricane season. It became the most destructive storm of the season, the costliest Atlantic hurricane since Hurricane Andrew in 1992 and remained the costliest until Hurricane Charley in 2004, and the deadliest since Hurricane Gordon in 1994. Georges killed 604 people, mainly on the island of Hispaniola, caused extensive damage resulting at just under $10 billion (US dollars in 1998) in damages and leaving nearly 500,000 people homeless in St. Kitts and Nevis, Puerto Rico, Hispaniola and Cuba.

The hurricane made landfall in at least six countries (Antigua and Barbuda, St. Kitts and Nevis, Haiti, the Dominican Republic, Cuba, and the United States), more than any other hurricane since Hurricane Inez of the 1966 season. Throughout its path of destruction, it caused extreme flooding and mudslides, as well as heavy crop damage. Thousands were left homeless as a result of the storm in the Lesser Antilles, and damage in those islands totaled abour US$880 million. In the Greater Antilles, hundreds of deaths were confirmed, along with over $2.4 billion in damages. Hundreds of thousands were left homeless, due to catastrophic flooding, torrential rainfall, and high storm surge. Flooding was exacerbated heavily by coastal defenses being broken from high waves. Crops were heavily damaged, and thousands of houses were destroyed due to mudslides.

Damage from Georges was extensive in the U.S. Virgin Islands and Puerto Rico as well. In Puerto Rico, the storm was the first hurricane to pass over the island since the 1932 San Ciprián hurricane. Storm surges 10 ft (3 m) high were recorded, along with damage across much of the country. Roads were rendered impassible, and beaches eroded due to heavy flooding. Some areas were left isolated. Crop damage was extreme, especially to the Banana plant. A total of 96 percent of the territory's population was left without power due to nearly half of the island's electrical lines being downed. A little under 73,000 houses had been damaged, with just over 28,000 others being destroyed. Due to no fully developed water systems being present, 75% water and sewage services had been lost. According to contemporary reports, Hurricane Georges caused $3.6 billion in damage in Puerto Rico. In September 2017, Governor Pedro Rosselló estimated the actual damage was around $7–8 billion.

In the United States, damage was widespread across multiple states. In Florida, high storm surge caused flooding. All of Florida Keys were left without power. In Miami, over 200,000 had no power due to winds knocking down power lines. 17 tornadoes were confirmed throughout the state. Rainfall as high as 38.46 in (977 mm) was recorded, which caused devastating flooding. Thousands of homes were damaged throughout the state. In Louisiana, impacts were mostly minor. Evacuations were well-timed, and lead to 0 deaths in the state. 3 died indirectly, however: 2 men collapsed and died due to stress, and a house burned down because of a candle being tipped over, killing one. In Mississippi, rainfall as high as 25 inches was recorded. Homes were flooded and people were forced to evacuate days after the storm had passed. Mobile homes were damaged and/or overturned. In Alabama, 25 ft (7.6 m) high waves were recorded. Homes, apartment buildings, and businesses were damaged. 20 tornadoes touched down, with one causing over $1.5 million. 29 in (740 mm) rainfall accumulation was recorded. Many bridges, highways, and roads were shut down due to flooding. The only direct death in the US was recorded in the state. In Georgia, damage was minor. Rainfall accumulating to about 7 inches (180 mm) closed several roads across multiple counties. The name Georges was retired due to extreme damage caused by the storm.

Meteorological history

Tropical storm (39–73 mph, 63–118 km/h)

Category 1 (74–95 mph, 119–153 km/h)

Category 2 (96–110 mph, 154–177 km/h)

Category 3 (111–129 mph, 178–208 km/h)

Category 4 (130–156 mph, 209–251 km/h)

Category 5 (≥157 mph, ≥252 km/h)

Unknown

A tropical wave exited the coast of Africa on September 13. Moving westward, the large system quickly developed a closed circulation, and was classified Tropical Depression Seven on September 15. A strong upper-level ridge forced the depression to the west-northwest, where warm water temperatures allowed it to strengthen to a tropical storm on September 16. Georges's circulation developed strong banding features around a well-organized Central Dense Overcast, and with the aid of a developing anti-cyclone, Georges attained hurricane status late on September 17.[1]

Conditions became nearly ideal for continued development, including warm water temperatures, low-level inflow to the hurricane's north, and good upper-level outflow. A banding eye developed, and Georges reached major hurricane strength on September 19 while 675 mi (1085 km) east-southeast of Guadeloupe. By September 19, an upper-level anticyclone was well established over Georges and satellite pictures suggested that the hurricane was beginning to strengthen rapidly, as indicated by the cooling cloud tops, increased symmetry of the deep convection, and the warming and contracting of the well-defined 40 mi (64 km) wide eye as rapid intensification continued, and Georges peaked as a very dangerous and a high-end Category 4 storm with 155 mph (249 km/h) wind and a 937 minimal pressure late on September 19 and early September 20. At that time, Georges was the most intense, strongest storm since Hurricane Hugo and along with Hurricane Luis, it is one of the largest major hurricanes in the south Atlantic with hurricane force windfields extending more than 115 mi (185 km) from the north and with a more than 300 mi (480 km) wide tropical storm force windfield. Shortly after peaking, upper-level wind shear from the development of an upper-level low weakened the hurricane on September 20 in the afternoon, as the central pressure had risen 26 mb as Georges approached the Leeward Islands.[1]

On September 21, after weakening considerably, Category 3 Georges made landfall directly on Antigua and three hours later in St. Kitts, though its 175 mi (282 km) wide tropical storm force windfield affected all the Leeward Islands. After weakening to a Category 2 hurricane over the Caribbean, upper-level shear decreased, and Georges strengthened a bit before making landfall near Fajardo, Puerto Rico as a 115 mph (185 km/h) Category 3 hurricane early in the morning. Over the mountainous terrain of the island, the hurricane weakened again, but over the Mona Passage it again re-intensified to hit eastern Dominican Republic with winds of 120 mph (190 km/h) on September 22. Like in Puerto Rico, Georges was greatly weakened by the mountainous terrain, and after crossing the Windward Passage, it struck 30 mi (48 km) east of Guantánamo Bay, Cuba on September 23. Well-defined upper-level outflow allowed the hurricane to remain well organized, and while paralleling the northern coastline of the island Georges retained minimal hurricane status.[1]

Hurricane Georges reached the Straits of Florida on September 24, and as it had done earlier in its lifetime, quickly restrengthened to Category 2 status on the September 25 due to warm water temperatures and little upper-level shear. It continued to the west-northwest, and struck Key West later on September 25 with winds of 105 mph (169 km/h). Despite moving over warmer water, Georges only managed to peak at 110 mph (180 km/h) in the Gulf of Mexico, likely due to its disrupted inner core. A mid-tropospheric anticyclone pushed the hurricane slowly north-northwestward, forcing Georges to make its seventh and final landfall near Biloxi, Mississippi on September 28. Within 24 hours, Georges had weakened to a tropical depression, and due to weak steering currents the storm looped over southern Mississippi, then drifted to the east. The weak circulation moved eastward over the interior of the Florida Panhandle, and dissipated on October 1 near the Florida/Georgia border.[1]

Preparations

Lesser Antilles

Late on September 18, a hurricane watch was issued for Saint Lucia, Anguilla, Saba, and Sint Maarten; it was extended to include the British and United States Virgin Islands on the following day. Later on September 19, a hurricane warning was put into effect for islands between Dominica and Anguilla, as well as Saint Martin, but excluding Saint Barthélemy. Early on the following day, a tropical storm warning was issued for Saint Lucia and Martinique. About six hours later, the hurricane warning issued on September 19 was extended on September 20 to include islands north and west of Dominica until Puerto Rico. Simultaneously, the tropical storm warning in effect for Saint Lucia and Martinique was discontinued. By later on September 21, the hurricane warning was canceled for all islands east of the Virgin Islands including Antigua, Barbuda, St. Barthelemy, St. Martin. At 0300 UTC on the following day, the hurricane warning was extended to include the British and United States Virgin Islands, though six hours later, it was also discontinued.[1]

Several hundred people on the island of Montserrat went into twelve hurricane shelters as Georges passed by with winds of 110 mph (180 km/h).[2] On September 18, the National Disaster Preparedness Committee in Dominica began meetings to prepare for possible impacts from Georges. Residents began stocking up on supplies by this time. For the following two days, the island was placed under a state of high-alert as direct impact from a Category 4 hurricane was anticipated. By the following morning, most businesses had boarded up their windows and roads were quiet. Officials declared that schools would be closed on September 21 and shelters across the island were opened.[3]

Greater Antilles

Beginning at 21:00 UTC on September 21 with a hurricane watch for Puerto Rico, the NHC and national governments in the Greater Antilles and the Bahamas issued a number of tropical cyclone watches and warnings in anticipation of the hurricane. As the storm progressed across the islands, the warnings were gradually canceled, until the Government of Cuba discontinued a hurricane watch at 03:00 UTC on September 26.[1]

In the days prior to the hurricane's arrival, thousands of citizens in the Leeward Islands and Puerto Rico prepared for the major hurricane by boarding windows and purchasing supplies. Puerto Rican governor Pedro Rosselló activated the island's National Guard, opened 416 shelters, and enacted a temporary prohibition on alcohol sales. More than 28,000 people across the island evacuated their homes to the shelters in the northern portion of the island. Both the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and the American Red Cross deployed workers there with supplies for a potentially deadly event.[4][5]

Due to initial forecasts of the hurricane brushing the northern portion of the country, the Dominican Republic was caught off guard. Instead, like in Puerto Rico, Georges traversed the entire country, and passed close to Santo Domingo. Neighboring Haiti expected the worst, opening shelters and evacuating vulnerable people from low-lying coastal areas.[6]

Prior to making landfall, more than 200,000 people were evacuated from coastal areas in eastern Cuba. In the potentially impacted area, Cuba's revolutionary army was sent to farm lands to harvest crops that could be destroyed during the storm. Members of the Cuban government travelled door-to-door to alert everyone of the hurricane. In addition to this, President Fidel Castro spoke live on national television to explain the country's plans to withstand the hurricane, as well as ensuring a quick recovery effort by using all of the nation's resources.[7]

United States

Initial forecasts of a southeastern Florida landfall forced over 1.2 million to evacuate, including much of the Florida Keys. Despite the mandatory evacuation order, 20,000 people, including over 7,000 Key West citizens, refused to leave. Some of those who remained to ride out the storm were shrimpers, whose boats were their entire livelihood. Insurance companies refused to insure some of the older shrimp boats, leading shrimpers to ride it out with all they had left.[8] Due to lack of law enforcement, those who stayed in Key West went through red lights, double-parked, and disobeyed traffic laws. Long-time Florida Keys citizens noted the solitude of the time and enjoyed the island for how it once was, rather than the large crowds of tourists.[9]

In the northern Gulf of Mexico, Georges was forecast to attain major hurricane status and make landfall in southeastern Louisiana. Because of this, portions of the state were evacuated, including New Orleans. There, the Louisiana Superdome was, for the first time in its history, used as a refuge of last resort for those unable to evacuate New Orleans. More than 14,000 citizens rode out the storm in the facility, causing difficulties to supply necessities. The building had no problems related to the weather, though evacuees looted the building, stole furniture, and damaged property. However, the damage was much less than in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina in 2005. Many citizens in southern Mississippi were told to leave due to a mandatory or recommended evacuation. Of those in the evacuation area, 60% actually left. Most of those who stayed remained because they believed their house was safe enough for the storm. Of those who left, most went to a relative's house in their own county.[10] Prior to making landfall, Georges's track was very uncertain. This forced for the mandatory evacuations of Alabama's two coastal counties, Baldwin and Mobile Counties, with a combined population of over 500,000 people.[11] Despite the order, only 67% of the area actually left to a safer place. Most of those who remained stayed because they believed their house would be able to withstand the hurricane. The majority of those who did leave went to a relative's house in a safer portion of the state.[10] In the days before making landfall, only 22% of the population in recommended evacuation areas along the Florida Panhandle actually left. However, most of them were prepared to leave if the situation became worse. Those who did leave were concerned about the severity of the storm, while those who stayed felt their home was safe enough for the hurricane's effects. Floridians who evacuated typically left for a friend or relative's house, and only went to another area of their county.[10]

Impact

| Country | State | Deaths | Damage | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antigua and Barbuda | 3 | $59.4 million | [12] | |

| Guadeloupe | 0 | $20 million | [13] | |

| St. Kitts and Nevis | 5 | $800 million | [14] | |

| British Virgin Islands | 0 | $9.4 million | [12] | |

| Dominican Republic | 380 | $2 billion | [14] | |

| Haiti | 209 | $179 million | [15] | |

| Bahamas | 1 | Unknown | ||

| Cuba | 6 | $306 million | [16] | |

| United States | U.S. Virgin Islands | 0 | $3.5 billion | [17] |

| Puerto Rico | 7 | |||

| Alabama | 1 | $2.5 billion | [17] | |

| Florida | 0 | |||

| Georgia | 0 | |||

| Louisiana | 3 | |||

| Mississippi | 0 | |||

| Total | 604 | $9.37 billion | ||

A large and long-lasting hurricane, Hurricane Georges brought torrential rainfall and mudslides along much of its path through the Greater Antilles. In all, the hurricane caused at least $9.37 billion in damage and 604 fatalities. In the two months after Georges's final landfall, the American Red Cross spent $104 million on relief aid through Puerto Rico, the United States Virgin Islands, Florida, Louisiana, Alabama, and Mississippi, making Georges the costliest disaster aid in the program's 125-year history.[1]

Leeward Islands

Upon moving through the Leeward Islands, Georges brought strong winds and heavy rainfall, amounting to a maximum of 7.5 inches (190 mm) at St. John.[1]

Antigua

In Antigua, strong winds caused severe property damage, mostly caused to roofs. 10–20% of houses were greatly impacted, including three schools. High winds during the passage of the hurricane downed telephone and power lines, causing loss of communication and power across much of the island.[19] An unofficial wind observation from Antigua reported winds at 94 mph with gusts to 116 mph.[20] Between Barbuda and Antigua, Georges killed 3 people, left 3,800 homeless and resulting at $60 million damage.[21]

Guadeloupe

The weakening hurricane spared the island as it passed 27 miles (43 km) to the north, causing moderate damage (houses and roofs, uprooted trees, power lines and outages, beach erosion) especially in Grande-Terre. In Basse-Terre, minor to moderate damage was common; the worst damage was to the banana crops, 85% to 100% devastated, with a cost of 100 million francs (22 million USD). The maximal rainfall was up to 6.7 inches (170 mm) in the mountainous area.

The Met office in Desirade, east of Guadeloupe had a 75 miles per hour (121 km/h) wind and a 89 miles per hour (143 km/h) sustained gust. In Raizet, they experienced a 48 miles per hour (77 km/h) wind and a maximal gust near 72 miles per hour (116 km/h). The minimal pressure fell to 1000–1001 mb (29.54 IHg) for several hours.

Météo France forecast 24 hours before the impact a 65 mph sustained winds with max gust in the 90–100 mph and a minimal pressure in the 985–990 mb range in the main station in Raizet, meaning the worst has been avoid.

St. Kitts and Nevis

After passing through Antigua, Georges produced strong winds of up to 115 mph (185 km/h) while passing over St. Kitts, Georges caused catastrophic damage downing power lines, telephone lines, and trees across the island. Lack of electricity resulted in damage to water facilities, as well. Georges's high winds caused extensive property damage, damaging 80–85% of the houses on the island, and destroying 20–25% of homes. Many schools, businesses, hospitals, and government buildings lost their roofs, while the airport experienced severe damage to its main terminal and control tower, limiting flights to the daytime. St. Kitts' economy was disrupted from severe agricultural losses, including the devastation of 50% of their sugar crop. In addition, damaged hotels and piers created a long-term impact through lack of tourism—an industry the island relies on. In all, Hurricane Georges caused 5 fatalities, left 3,000 homeless, and resulted in $458 million (1998 USD) in damage on the island.[22]

In the other part of the country, Nevis fared better. Like on St. Kitts, high winds downed power and telephone lines, damaging the water system there. 35% of homes on the island were damaged, though none were destroyed. Rainfall and debris killed several hundred livestock and seriously damaged coconut trees, amounting to $2.5 million (1998 USD) in agricultural damage. There were no casualties reported on the island, and damaged amounted to $39 million (1998 USD).[22]

Damage in St. Kitts totaled EC$1.2 billion (US$458 million).[23] Total damage on Nevis amounted to $39 million.[24] The total damage from the storm was nearly twice the country's Gross Domestic Product of US$271 million.[25]

British Virgin Islands

No major damage was reported to public buildings in the British Virgin Islands. Some of the islands' homes had roofs blown off. The environment suffered major damage. There were many reports of eroded soil in areas where construction was in progress. Some of the soils were planted on roads in mangrove farms and in the sea, which could have potentially killed sea life.[12] National Parks around the islands suffered minor damage except for Queen Elizabeth Park, which had many fallen trees. None of the schools in the area suffered any damage and opened again four days after Georges had passed. There were no fatalities in the islands and one minor injury was reported. There was no major damage to the islands' medical buildings. Pipe damage was found in two areas, but there was no damage to the sewage systems. The total damage in the British Virgin Islands was valued at US$9.404 million.[12]

U.S. Virgin Islands and Puerto Rico

U.S. Virgin Islands

As Georges moved through the northern end of the Lesser Antilles, it produced significant rainfall and strong winds over the United States Virgin Islands. Maximum rainfalls reached 6.79 inches (172 mm) at the airport in St. Croix and 5.26 inches (134 mm) at St. Thomas Airport. The strongest sustained winds and gusts were recorded on St. Croix as well, measuring 74 and 91 mph (119 and 146 km/h) respectively.[26]: 110 A total of 20 homes were destroyed and 50 others sustained damage. Most of the losses were confined to agriculture and livestock.[27] Fifty-five boats were sunk across the islands. Several power lines were downed throughout St. Croix by high winds, leaving some residences without power.[26]: 110 However, compared to the intensity of Georges during its passage of the islands, relatively few people, 15% of the island's customers, lost power. This was due to the improved power grid set up across the island for this type of event.[28] Total losses on the island were estimated at $2 million (1998 USD).[29]

In other nearby islands, Georges impact was relatively minor to moderate. Power outages, flooding, and minor to moderate structural damage was common.[11]

Puerto Rico

Georges was the first hurricane to cross the entire island of Puerto Rico since the San Ciprian hurricane in 1932.[30] The hurricane brought storm surge peaking at an estimated 10 ft (3.0 m) in height in Fajardo, along with tides up to 20 ft (6.1 m) above normal.[1][31] The hurricane spawned two F2 tornadoes on the island, though they caused little damage. Georges dropped immense precipitation in the mountain regions, peaking at 30.51 in (775 mm) in Jayuya with many other locations reporting at least 1 ft (300 mm) of precipitation.[1][32] Hurricane-force winds were observed throughout the island. Sustained winds and gusts reached 87 and 107 mph (140 and 172 km/h), respectively, at the Roosevelt Roads Naval Station in Ceiba. Unofficially, a sustained wind speed of 102 mph (164 km/h) and a gust of 164 mph (264 km/h) were observed in Isabela.[1]

The mountain flooding drained off in the island's rivers, causing every river to overflow its banks. Near the coast, the surfeit of water carved new channels from the record discharge rate. The storm's strong winds caused beach erosion in many places along the coastline. Eroded beaches, flooding, and debris left many roads impassable or destroyed, isolating some areas on the western portion of the island.[30] Georges's deluge of rainfall caused significant damage to the agricultural industry, including the loss of 75% of its coffee crop, 95% of its banana or plantain crop, and 65% of its live poultry.

Its large circulation brought fierce winds to the entire island, damaging 72,605 houses and destroying 28,005 others. This left tens of thousands homeless after the storm's passage.[1] Over 22,000 people were sheltered in 139 shelters in cities throughout the island. All shelters experienced power outages, and after the storm passed through, lack of water and sewer systems became a serious problem.[10] High winds downed nearly half of the island's electric and telephone lines, leaving 96% of the population powerless and 8.4% of telephone customers without service. Lack of electricity greatly damaged the water system, resulting in the loss of water and sewer service for 75% of the island.[30] In the nearby small island of Culebra, Georges destroyed 74 houses and damaged 89 others, although damage estimates are not available there.[30]

In all, Georges caused $3.6 billion in damage and there were no direct casualties due to well-executed warnings.[1] However, Georges indirectly caused eight deaths in Puerto Rico. Two deaths occurred due to carbon monoxide poisoning from operating a gasoline-powered generator indoors, while two other people were hospitalized for the same issue. Four other fatalities occurred after a lit candle started a house fire. Additionally, there was one death each from head trauma and electrocution in the aftermath of the hurricane.[33]

On September 24, 2017, nineteen years after the storm, Puerto Rico's Governor Pedro Rosselló estimated that the damage was probably between $7 and $8 billion.[18] Repairs had been made to the roofs, crops (plantains, poultry, coffee, and sugar cane), and transportation system. The damage done by the hurricane had a serious impact on the economy, as much of the main sources of production were destroyed and many of the island's inhabitants had been forced to move from their homes. The lifestyle of many Puerto Ricans was also forced to change, as many of their farms were left damaged beyond repair. The recovery funds were used not only for restoration, but also for staff to aid the island. FEMA brought about temporary roofing for those whose roofs were torn apart. The U.S. Army also brought about one million blocks of ice and one million gallons of water, in order to compensate the effects of the loss of 95% of power across the island. In 2019, damage from Georges was still being repaired, as there was not enough money funded to repair all of the damage caused by the hurricane. Additionally, more money is needed to regrow the crops destroyed by the storm.[34]

Greater Antilles

Hispaniola

Though there are no recorded amounts, satellite-derived rainfall estimates show up to 39 inches (990 mm) of rain falling in the mountainous terrain of the countries. This heavy rainfall resulted in mudslides and flooding, killing a total of 589 people across the island and leaving more than 350,000 homeless.[1]

Dominican Republic

In the Dominican Republic, Georges brought strong winds and very heavy rains, along with a 7-foot (2.1 m) storm surge. Nearly 10 hours of continuous rainfall resulted in mudslides and overflown rivers across the mountainous country, damaging many cities along the southern coastline, including the capital. 120 mph (193 km/h) winds downed and uprooted trees across much of the country, littering streets with debris and mud. Thousands of houses were destroyed, while many were completely destroyed from the flooding and winds. The entire country was without electricity during the aftermath of the storm, damaging water and communication systems.[35] Heavy wind damage and flooding caused extensive damage to the airport in Santo Domingo, restricting usage to military and non-commercial flights.[36]

Most impacted by Hurricane Georges was the agricultural industry. The areas hardest hit by the hurricane coincided with the country's main crop-growing areas, including the provinces around Santo Domingo. After a severe drought in 1997, extreme rainfall damaged around 470,000 acres (190,202 ha) of food crops, including various types of vegetables, fruits, and roots — some of the country's main diet food. Substantial amounts of tobacco and sugar plantations, the country's most important export crop, were severely damaged. The extreme flooding caused great losses in the poultry industry, an important economy in the area. The Dominican Republic had to import significant amounts of rice and other crops to compensate for the losses.[37]

Death toll reports were slow in the wake of the storm, but a total of 380 people died from Hurricane Georges and leaving more than 185,000 homeless.[1] Damage in the Dominican Republic amounted to $1.8 billion (1998 USD).[38]

Haiti

Upon reaching Haiti, Georges was a weakened hurricane, but it still brought heavy rainfall across the entire country. The capital city of Port-au-Prince was largely unharmed, with the exception of flooding in low-lying coastal areas, damaging the main commercial port.[36] The rest of the country, however, experienced a significant number of mudslides due to deforestation along the mountains.[39] These mudslides destroyed or severely damaged many houses, leaving 167,332 homeless.[1] Damage was greatest along the northern coastline from Cap-Haïtien to Gonaïves due to the flooding and mudslides.[40] On the southern coast, the head of a U.S.-based medical team, stranded for several days by flooding in the remote town of Belle Anse, anticipated a rise in malnutrition, disease, homelessness and poverty.[41][42] Lack of electricity led to a total disruption of Haiti's water supply system, causing a decrease in sanitary conditions across the poorest country in the Western Hemisphere.[43] In all, 209 people died in Haiti.[1]

Like in the Dominican Republic, the agricultural sector suffered extreme damage. After a severe drought in 1997, Georges's severe flooding stopped any chances of recovering quickly. Most of the country's significant crop land, including Artibonite Valley, suffered total losses. Up to 80% of banana plantations were lost, while vegetable, roots, tubers, and other food crops were ruined. In addition, thousands of small farm animals were either killed or lost.[37] Total agricultural losses amounted to $179 million (1998 USD, $250 million 2009 USD).[44] The country requested food assistance in the aftermath of the hurricane to alleviate the serious losses.[37]

Cuba

Upon making landfall, Hurricane Georges produced torrential rainfall, amounting to a maximum of 24.41 inches (620 mm) at Limonar in the province of Guantánamo. Several other locations reported over a foot (300 mm) of precipitation as well.[1] Storm surge of 4–6 feet (1.2–1.8 m) was expected along the eastern coastline, along with dangerous waves on top of the surge. Though winds were reduced by the time Georges hit Cuba, it still retained winds of 75 mph (121 km/h), along with stronger gusts in squalls.[45]

The hurricane's heavy rainfall resulted in mudslides along the mountainous terrain. This, combined with strong winds, damaged 60,475 homes, of which 3,481 were completely destroyed.[1] In the country, 100,000 were left homeless due to Hurricane Georges.[46] High winds downed power lines, trees, and telephone poles, leaving many in eastern Cuba without electricity in the aftermath of the storm. Along the coast, severe flooding washed out railroad and highway bridges. Though eastern Cuba was the area most affected, the central and western portion of the island, including Havana, experienced torrential rains and strong wind gusts.[47] There, strong waves broke over the seawall, and caused heavy flood damage to some of the town's old buildings.[48]

Like in Puerto Rico and Hispaniola, the severe drought during the El Niño of 1997 exacerbated the flood's disruption to crops in eastern Cuba. The heavy rainfall from Georges damaged the crops greatly, despite the effort to harvest them prior to its arrival. Up to 70% of the plantain crop, a chief food in the country's diet, was destroyed. The sugarcane crop fared badly as well, limiting one of the country's important export crops. The coffee and cocoa plantations also suffered from the hurricane, further damaging the country's food supply.[37]

Well-executed evacuations and warnings limited the death toll to six,[1] while damage amounted to $305 million (1998 USD, $500 million 2009 USD).[14]

Bahamas

Though Georges was forecast to move through the Bahamas, it passed to the south of the archipelago. It brought 70 mph (110 km/h) winds to Turks and Caicos Islands and South Andros, as well as precipitation in the storm's outer bands. Though damage was minimal, one person died in the country.[1]

United States

Throughout the mainland areas of the United States, Georges left approximately $2.5 billion in damage. The hurricane ranked as the country's fifth costliest hurricane at the time of its occurrence. Due to extensive preparations, only one direct death was attributed to the storm. A tornado outbreak produced 47 tornadoes–20 in Alabama, 17 in Florida, and 10 in Georgia, leaving 36 injuries and about $9 million in damage.

Florida

In the Florida Keys, Georges brought a storm surge of up to 12 ft (3.7 m) in Tavernier.[8] The islands, some only 7 ft (2.1 m) high and 300 yd (270 m) wide, flooded easily.[9] Tides reaching about 10 ft (3.0 m) above normal inundated many parts of the Overseas Highway. Strong winds downed palm trees and power lines, leaving all of the Keys without power. Georges's waves overturned two boats in Key West,[8] damaged 1,536 houses, and destroyed 173 homes, many of which were mobile homes. Rainfall amounted to a maximum of 8.41 in (214 mm) in Tavernier, while other locations reported lesser amounts.[1] Damage in the Florida Keys amounted to $200 million.[49] Strong winds knocked down power lines, leaving 200,000 without power in the Miami area.[8]

Georges produced a storm surge of up to 10 ft (3.0 m) in the Florida Panhandle.[1] Some roads were completely washed away in Pensacola Beach and Navarre Beach.[50] The storm surge and waves flattened about 1,125 ft (343 m) of dunes. Between Panama City Beach and Perdido Key, most of the beach access stairs and walkways suffered damage.[51] As the storm moved slowly through the northern Gulf Coast, it produced torrential rainfall amounting to a maximum of 38.46 in (977 mm) in Munson, causing extensive inland flooding. Several rivers and creeks in the western Florida Panhandle reached record or near-record levels, including the Blackwater River at Baker, the Yellow River at Milligan, and the Shoal River at Crestview.[50] Hundreds of homes along these rivers were flooded, with at least 200 homes damaged in Santa Rosa County and at least 639 homes damaged and 7 others destroyed in Escambia County.[52][53] The storm left about $100 million in damage in the Florida Panhandle.[49]

Throughout the state, the storm spawned 17 tornadoes – the largest outbreak in the state since Hurricane Agnes in 1972.[54] The strongest tornado, rated F2 on the Fujita scale, touched-down in Suwannee County near Live Oak, destroying 1 mobile home,[55] 7 homes,[26]: 22 and 12 cars,[55] while 5 other structures suffered damage.[26]: 22 Several residents were tossed out of their homes.[56] Five people were injured and damage from the tornado reached over $1 million.[26]: 22 [57] Overall, damage in Florida totaled at least $340 million.[1]

Louisiana

Upon making landfall in Mississippi, Georges brought a storm surge peaking at 8.9 ft (2.7 m) near Pointe a la Hache, along with higher waves on top of it, though the instrument failed shortly after the observation. The storm surge caused extensive beach erosion, with nearly 1,200 ft (370 m) of sand was lost, including 6 ft (1.8 m) sand dunes, leaving boardwalks formerly situated atop the dunes suspended near the water's surface. The storm surge also inundated the Chandeleur Islands, the first line of protection for the coasts of Louisiana and Mississippi. The long island chain was reduced to a few banks of sand in the Gulf of Mexico. Grand Gosier, the home to a flock of brown pelicans, experienced severe flooding, destroying their habitats.[49] Located on the weaker side of the storm, rainfall totals in Louisiana were low, with a maximum amount of 2.98 in (76 mm) in Bogalusa.[1]

Sustained winds in the state reached 48 mph (77 km/h) and gusts peaked at 68 mph (109 km/h).[1] High winds downed power lines, leaving 160,000 without electricity across the state.[58] At least 50 homes located outside the levee system were flooded by the storm surge, while 85 fishing camps on the banks of Lake Pontchartrain were destroyed. Overall, impact from the hurricane was fairly minor, with damages estimated at $30.1 million, but no direct deaths due to well-executed evacuations.[1] However, there were three indirect fatalities in the state. Two men collapsed and died due to medical conditions aggravated by the stress of the evacuation; the other death occurred as the result of a house fire ignited by an emergency candle that was tipped over.

Mississippi

Upon making landfall, Hurricane Georges brought a storm surge of up to 8.9 ft (2.7 m) in Biloxi. Beach erosion occurred along the coastline, resulting in some property damage on beach houses. However, around Biloxi, coastal casinos and the shipyards experienced little damage from the storm.[59] While stalling over the southern portion of the state, it produced torrential rainfall, amounting to 16.7 in (420 mm) in Pascagoula. The heavy rainfall contributed to significant river overflowing, including the Tchoutacabouffa River at D'Iberville, which set a record crest of 19 ft (5.8 m). The overflown rivers in the southern portion of the state flooded homes and forced more to evacuate just days after the hurricane came through.[1] Along the coast of Mississippi, more than 1,000 homes were flooded.[60] One of the worst impacted areas inland was Stone County, where 54 homes had minor damage, 26 suffered major damage, and 5 were destroyed. In addition, squall lines spawned multiple tornadoes, damaging evacuation shelters in Pascagoula and Gautier.[58]

One location observed hurricane-force winds, with a sustained wind speed of 75 mph (121 km/h) at Keesler Air Force Base. In Harrison County, winds downed power lines, signs, and traffic lights, while damaging some roofs. Impact was similar but more severe in Jackson County, with more considerable damage to the roofs of some buildings, while a few mobile homes were damaged or overturned. Throughout the state, winds left approximately 230,000 people without power.[11] After the storm, over 6,800 people stayed in 49 shelters. One shelter in Forrest County was damaged, forcing the citizens to another camp.[10] Overall, Hurricane Georges caused about $676.8 million in damage, though no deaths were reported.[1]

Alabama

Upon making landfall, storm surge heights along the coast of Alabama were estimated to have ranged from 7 to 12 ft (2.1 to 3.7 m), with a peak of 11.9 ft (3.6 m) in Fort Morgan, along with 25 ft (7.6 m) waves on top of it.[1][61] Along the coastline, heavy rainfall and strong waves caused extensive property damage. In Gulf Shores, 251 houses, 16 apartment buildings, and 70 businesses experienced significant damage. On Dauphin Island, the hurricane damaged 80 houses and left around 40 uninhabitable.[49] Many waterfront homes on the western side of the island were pushed into other homes or strewn into pieces across the sand. Some roads were completely washed away. In Orange Beach, two condominiums were heavily damaged, one by fire and the other by high waves. Extensive storm surge flooding also occurred along Mobile Bay. With storm surge of 8.0 ft (2.4 m) at Mobile Bay Causeway, a number of businesses near the bridge were damaged.

Sustained winds in Alabama reached 54 mph (87 km/h) at Mobile Aeroplex at Brookley, while gusts peaked at 64 mph (103 km/h) at an agricultural station in Fairhope.[1] High winds downed power lines and trees, leaving 177,000 people without power after the storm.[61] A total of 17 shelters housed 4,977 people in the aftermath of the storm. Wind damage to the buildings was minimal.[10][62] The storm spawned 20 tornadoes throughout Alabama. The most devastating tornado touched-down in Enterprise, causing severe damage to Camp Wiregrass and a few homes, while many residences in the city were left without electricity after numerous power lines were downed. Damages from the tornado amounted to roughly $1.5 million.

While moving slowly through the state, it dropped torrential rainfall, peaking at 29.66 in (753 mm) in Bay Minette. Outer squalls spawned tornadoes in the southeast portion of the state, though damage from them was minimal.[1] Several rivers in southern Alabama crested at record or near record heights at some locations, including the Conecuh River at Brewton, Fish River, Perdido River, and Styx River. Many homes situated near the banks of these rivers were destroyed or suffered extensive damage. Flooding shut down many bridges, highways, and secondary roads in Baldwin and Escambia counties, including Interstate 10 near the Alabama–Florida state line; U.S. Route 29 and Alabama State Route 113 in Flomaton; and US 31 in Brewton and Flomaton. Overall, damage in Alabama amounted to $125 million. Freshwater flooding in Mobile resulted in one death, the only direct death in the United States.[1]

Georgia

In Georgia, several counties reported 5 to 7 in (130 to 180 mm) of rainfall, causing a number of roads to become impassable and generally leaving a small amount of damage, including up to $45,000 in damage in Quitman County.[26]: 34 and 37 In addition to the flooding, some instances of thunderstorm wind impacts also occurred. In Appling County, an intense thunderstorm related to Georges damaged 12 mobile homes and a vehicle and downed some power lines and large trees, with damage totaling about $65,000.[26]: 34 Another intense thunderstorm in Worth County impacted several residences, knocked a mobile home off its foundation, destroyed a barn, overturned a school bus, and downed a number of trees that fell onto power lines, leaving around $350,000 in damage.[26]: 36 Thunderstorms also toppled a tree onto a car in Macon County and ripped off the porch of a mobile home in Schley County.[26]: 35

Numerous tornadoes touched down across the state of Georgia in relation to Georges and its remnants. The most damaging tornado occurred in Miller County, with a strong F1 destroying a doublewide trailer, seriously injuring two occupants, and deroofing several outbuilding, twisting sheet metal, and demolishing a grain bin. Damage totaled approximately $750,000.[26]: 37 Three tornadoes impacted Sumter County, the first of which destroyed one home and seven mobile homes in De Soto and damaged several businesses, while more homes were struck by trees felled by the twister. The second tornado demolished one home and several mobile homes. A third tornado was spawned at a pecan grove near Andersonvile, although it may have been a continuation of the previous twister.[26]: 35

Retirement

Due to the extensive damage, the name Georges was retired following this storm, and will never again be used for an Atlantic hurricane.[63] It was replaced with Gaston in the 2004 season.[64]

See also

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 Guiney, John L. (January 5, 1999). Preliminary Report Hurricane Georges 15 September – 01 October 1998 (updated September 2014) (PDF). National Hurricane Center (Report). NOAA. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- ↑ Government of Montserrat (1998). "Montserrat This Week – 012". Government of Montserrat. Retrieved 2007-08-22.

- ↑ National Disaster Committee (September 21, 1998). "How Hurricane Georges, 1998, affected Dominica". A Virtual Dominica. Retrieved July 27, 2009.

- ↑ Staff writer (1998-09-21). "Hurricane Georges pounds Caribbean islands". Associated Press (via the Wayback Machine). Archived from the original on 2006-08-29. Retrieved 2007-08-24.

- ↑ Federal Emergency Management Agency (1998-09-28). "FEMA operates In both response and recovery modes after hurricane Georges hits Puerto Rico and heads toward Florida". ReliefWeb. Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2007-08-24.

- ↑ Staff writer (1998-09-22). "Georges tears across Dominican Republic". CNN (via the Wayback Machine). Archived from the original on 2006-02-05. Retrieved 2007-08-24.

- ↑ Greg Butterfield (1998-10-08). "Hurricane Georges: A tale of two systems". Workers World. Retrieved 2007-08-24.

- 1 2 3 4 Staff writer (1998-09-26). "Hurricane Georges spares Florida ... for now". CNN (via the Wayback Machine). Archived from the original on 2006-12-23. Retrieved 2007-08-24.

- 1 2 Staff writer (1998-09-24). "Widespread South Florida evacuation urged". CNN (via the Wayback Machine). Archived from the original on 2006-12-17. Retrieved 2007-08-24.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Post, Buckley, Schuh & Jernigan, Inc. (August 1999). "Hurricane Georges Assessment: Review of Hurricane Evacuation Studies Utilization and Information Dissemination" (PDF). United States Army Corps of Engineers / Federal Emergency Management Agency. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 26, 2007. Retrieved 2007-08-24.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - 1 2 3 "Hurricane Georges' damage reports". USA Today. Associated Press. 2002. Retrieved 2007-08-24.

- 1 2 3 4 Pan American Health Organisation (1998-11-25). "IMPACT OF HURRICANE GEORGES ON HEALTH SECTOR RESPONSE". Pan American Health Organisation. Archived from the original on 2006-01-14. Retrieved 2007-08-23.

- ↑ "EM-DAT | the international disasters database".

- 1 2 3 Pielke, Roger A.; Rubiera, Jose; Landsea, Christopher; Fernández, Mario L; Klein, Roberta (August 1, 2003). "Hurricane Vulnerability in Latin America and The Caribbean: Normalized Damage and Loss Potentials" (PDF). Natural Hazards Review. American Society of Civil Engineers, Council on Natural Disaster Reduction. 4 (3): 101–114. doi:10.1061/(ASCE)1527-6988(2003)4:3(101). ISSN 1527-6988. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 19, 2012. Retrieved November 28, 2012.

- ↑ Office of U.S. Foreign Disaster Assistance (1998-10-08). Eastern Caribbean, Dominican Republic, Haiti — Hurricane Georges Fact Sheet #9, Fiscal Year (FY) 1999 (Report). United States Agency for International Development. Archived from the original on 2013-03-18. Retrieved 2007-08-24.

- ↑ International Federation of Red Cross And Red Crescent Societies (March 22, 1999). Caribbean — Hurricane Georges Situation Report No. 3 (PDF) (Report). ReliefWeb. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 26, 2013. Retrieved November 28, 2012.

- 1 2 Costliest U.S. tropical cyclones tables update (PDF) (Report). United States National Hurricane Center. January 12, 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 27, 2018. Retrieved January 12, 2018.

- 1 2 Jose de Cordoba (September 24, 2017). "Puerto Rico Tallies up Devastation from Hurricane Maria". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved Sep 25, 2017.

- ↑ Caribbean Disaster Emergency Response Agency (1998-09-21). "Impact situation report #2 – Hurricane Georges". ReliefWeb. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved 2007-08-24.

- ↑ "Georges". Archived from the original on 2009-08-20.

- ↑ Gary Padgett (September 1998). "Monthly Global Tropical Cyclone Summary". Archived from the original on 2007-09-29. Retrieved 2007-08-24.

- 1 2 "Hurricane Georges". St. Kitts/Nevis History Page. 2001-10-16. Archived from the original on 2006-06-20. Retrieved 2007-08-24.

- ↑ Office of U.S. Foreign Disaster Assistance (October 8, 1998). "Caribbean: Hurricane Georges OFDA-09: Fact Sheet #9". Disaster Information Center. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved July 26, 2009.

- ↑ Staff Writer (October 16, 2001). "Hurricane Georges: St. Kitts and Nevis". St. Kitts/Nevis History Page. Archived from the original on June 20, 2006. Retrieved July 27, 2009.

- ↑ Denzil L. Douglas (December 10, 1998). "St. Kitts and Nevis Letter of Intent". Government of St. Kitts and Nevis. Retrieved July 29, 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 "Storm Data and Unusual Weather Phenomena" (PDF). Storm Data. Asheville, North Carolina: National Climatic Data Center. 40 (9). September 1998. ISSN 0039-1972. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 13, 2021. Retrieved August 15, 2017.

- ↑ NOAA (1998). "Georges Pummels Caribbean, Florida Keys, and U.S. Gulf Coast". NOAA. Archived from the original on 2007-08-21. Retrieved 2007-08-23.

- ↑ "FEMA News Photo taken on 09/24/1998 in US Virgin Islands". Federal Emergency Management Agency. September 24, 1998. Archived from the original on January 6, 2009. Retrieved April 22, 2010.

- ↑ Shawn P. Bennett; Rafael Mojica (1998). "Hurricane Georges Preliminary Storm Report". NOAA. Archived from the original on 2007-06-25. Retrieved 2007-08-23.

- 1 2 3 4 Shawn P. Bennett; Rafael Mojica. "Hurricane Georges Preliminary Storm Report". National Weather Service. Archived from the original on 2007-06-25. Retrieved 2007-08-24.

- ↑ "Hurricane Georges hits Puerto Rico and moves on". American Radio Relay League. 1998-09-22. Archived from the original on 2007-09-30. Retrieved 2007-08-24.

- ↑ David Roth. "Hurricane Georges — September 19 – October 1, 1998". Tropical Cyclone Rainfall Climatology. Retrieved 2007-08-24.

- ↑ CDC. "Deaths Associated with Hurricane Georges – Puerto Rico, September 1998". CDC. Retrieved 2007-08-27.

- ↑ US Department of Commerce, NOAA. "Hurricane Georges – September 1998". www.weather.gov. Retrieved 2019-05-17.

- ↑ "Updates from the Islands: Georges — Dominican Republic". Stormcarib.net. 1998. Retrieved 2007-08-24.

- 1 2 Office of U.S. Foreign Disaster Assistance (1998-09-25). "Caribbean, Dominican Republic, Haiti – Hurricane Georges Fact Sheet #2". ReliefWeb. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved 2007-08-24.

- 1 2 3 4 Economic and Social Development Department (1998-10-13). "Hurricane "Georges" Causes Extensive Crop Damage in Caribbean Countries". Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Archived from the original on 2007-11-06.

- ↑ Staff writer (1999-06-11). "Georges devastates Dominican Republic". USA Today. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 1999-04-29. Retrieved 2007-08-24.

- ↑ Michael Norton (1998-09-30). "Haiti Hurricane Death Toll Hits 147". Associated Press. Archived from the original on October 11, 2007. Retrieved 2007-08-24.

- ↑ Richard Stuart Olson; et al. (2001). "Hurricane Georges and the Dominican Republic". Special Publication 38 – The Storms of '98: Hurricanes Georges and Mitch. University of Colorado at Boulder (via the Wayback Machine). Archived from the original on 2005-09-25. Retrieved 2007-08-24.

- ↑ Clint Williams (1998-09-26). "Hurricane Georges: Cobb medical team stuck in Haiti". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. pp. A06.

- ↑ Gerónimo Lluberas (1998-09-26). "The Impact of Hurricane Georges on the area of Belle-Anse, Haiti" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on September 26, 2007. Retrieved 2007-08-24.

- ↑ Caribbean Disaster Emergency Response Agency (1998-09-26). "Impact Situation Report — Hurricane Georges — Republic of Haiti". ReliefWeb. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved 2007-08-24.

- ↑ Office of U.S. Foreign Disaster Assistance (1998-10-08). "Eastern Caribbean, Dominican Republic, Haiti — Hurricane Georges Fact Sheet #9, Fiscal Year (FY) 1999". United States Agency for International Development. Archived from the original on 2013-12-03. Retrieved 2007-08-24.

- ↑ Richard Pasch (1998-09-23). "Hurricane Georges Public Advisory Number 35". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2008-08-24.

- ↑ "Damage Reports from 1998". Hurricane City. Retrieved 2007-08-24.

- ↑ Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (1998-09-29). "OCHA Geneva Situation Report No. 5". United Nations. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved 2007-08-24.

- ↑ Staff writer (1998-09-27). "Cuba: 4 dead; thousands left without homes". Miami Herald. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved 2007-08-24.

- 1 2 3 4 Staff writer (1998-10-02). "Gulf Coast damage estimates trickle in for Georges". CNN. Archived from the original on February 9, 2005. Retrieved 2007-08-24.

- 1 2 Hurricane Georges – September 1998 (Report). National Weather Service Mobile, Alabama. November 2016. Retrieved August 15, 2017.

- ↑ Hurricane Earl and Hurricane Georges Beach and Dune Erosion and Structural Damage Assessment and Post-storm Recovery Plan for the Panhandle Coast of Florida (PDF) (Report). Florida Bureau of Beaches and Coastal Systems. January 1999. p. 12. Retrieved August 15, 2017.

- ↑ Heidi Hall (October 2, 1998). "Residents near rivers start cleaning up soggy homes". Pensacola News Journal. p. 1. Retrieved August 15, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Heidi Hall (October 4, 1998). "Panhandle totals damages as region begins to dry out". Pensacola News Journal. p. 16. Retrieved August 15, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Bartlett C. Hagemeyer (2008). 2008 Florida Governor's Hurricane Conference: Tornadoes and Tropical Cyclones (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

- 1 2 Karen Voyles (October 1, 1998). "Twister hits near Live Oak". The Gainesville Sun. p. 1C. Retrieved August 15, 2017.

- ↑ Karen Voyles (October 2, 1998). "Survivors tell of twister". The Gainesville Sun. p. 1B. Retrieved August 15, 2017.

- ↑ "Suwannee County eligible for aid". The Gainesville Sun. October 2, 1998. p. 8B. Retrieved August 15, 2017.

- 1 2 Staff writer (1998-09-29). "Georges deluges Gulf Coast". CNN (via the Wayback Machine). Archived from the original on 2006-12-13. Retrieved 2007-08-24.

- ↑ "Flood Observations: Damages and Successes" (PDF). Building Performance Assessment: Hurricane Georges In The Gulf Coast. Federal Emergency Management Agency (via the Wayback Machine). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-02-20. Retrieved 2007-08-24.

- ↑ "Life goes on in the wake of Hurricane Georges". Star-Banner. October 1, 1998. p. 4. Retrieved August 1, 2013.

- 1 2 Overall Impact

- ↑ Before and After Effects Archived September 26, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ National Hurricane Center (2009). "Retired Hurricane Names Since 1954". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2009-09-13.

- ↑ The Daily Gleaner (1991-06-01). "The changing faces of a cyclone". Archived from the original on January 7, 2016. Retrieved 2009-01-03.