| Polar bear Temporal range: Pleistocene-recent[1] | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| Female near Kaktovik, Barter Island, Alaska, United States | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Family: | Ursidae |

| Genus: | Ursus |

| Species: | U. maritimus |

| Binomial name | |

| Ursus maritimus | |

.svg.png.webp) | |

| Polar bear range | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Ursus eogroenlandicus | |

The polar bear (Ursus maritimus) is a large bear native to the Arctic and nearby areas. It is closely related to the brown bear, and the two species can interbreed. The polar bear is the largest extant species of bear and land carnivore, with adult males weighing 300–800 kg (660–1,760 lb). The species is sexually dimorphic, as adult females are much smaller. The polar bear is white- or yellowish-furred with black skin and a thick layer of fat. It is more slender than the brown bear, with a narrower skull, longer neck and lower shoulder hump. Its teeth are sharper and more adapted to cutting meat. The paws are large and allow the bear to walk on ice and paddle in the water.

Polar bears are both terrestrial and pagophilic (ice-living) and are considered to be marine mammals due to their dependence on marine ecosystems. They prefer the annual sea ice but live on land when the ice melts in the summer. They are mostly carnivorous and specialized for preying on seals, particularly ringed seals. Such prey is typically taken by ambush; the bear may stalk its prey on the ice or in the water, but also will stay at a breathing hole or ice edge to wait for prey to swim by. The bear primarily feeds on the seal's energy-rich blubber. Other prey include walruses, beluga whales and some terrestrial animals. Polar bears are usually solitary but can be found in groups when on land. During the breeding season, male bears guard females and defend them from rivals. Mothers give birth to cubs in maternity dens during the winter. Young stay with their mother for up to two and a half years.

The polar bear is considered to be a vulnerable species by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) with an estimated total population of 22,000 to 31,000 individuals. Its biggest threats are climate change, pollution and energy development. Climate change has caused a decline in sea ice, giving the polar bear less access to its favoured prey and increasing the risk of malnutrition and starvation. Less sea ice also means that the bears must spend more time on land, increasing conflicts with people. Polar bears have been hunted, both by native and non-native peoples, for their coats, meat and other items. They have been kept in captivity in zoos and circuses and are prevalent in art, folklore, religion and modern culture.

Naming

The polar bear was given its common name by Thomas Pennant in A Synopsis of Quadrupeds (1771). It was known as the "white bear" in Europe between the 13th and 18th centuries, as well as "ice bear", "sea bear" and "Greenland bear". The Norse referred to it as isbjørn ("ice bear") and hvitebjørn ("white bear"). The bear is called nanook by the Inuit. The Netsilik cultures additionally have different names for bears based on certain factors, such as sex and age: these include adult males (anguraq), single adult females (tattaq), gestating females (arnaluk), newborns (hagliaqtug), large adolescents (namiaq) and dormant bears (apitiliit).[5] The scientific name Ursus maritimus is Latin for "sea bear".[6][7]

Taxonomy

Carl Linnaeus classified the polar bear as a type of brown bear (Ursus arctos), labelling it as Ursus maritimus albus-major, articus in the 1758 edition of his work Systema Naturae.[8] Constantine John Phipps formally described the polar bear as a distinct species, Ursus maritimus in 1774, following his 1773 voyage towards the North Pole.[4][9] Due to its adaptations to a marine environment, some taxonomists like Theodore Knottnerus-Meyer have placed the polar bear in its genus Thalarctos.[10][11] However Ursus is widely considered to be the valid genus for the species based on the fossil record and the fact that it can breed with the brown bear.[11][12]

Different subspecies have been proposed including Ursus maritimus maritimus and U. m. marinus.[lower-alpha 1][13] However these are not supported and the polar bear is considered to be monotypic.[14] One possible fossil subspecies, U. m. tyrannus, was posited in 1964 by Björn Kurtén, who reconstructed the subspecies from a single fragment of an ulna which was approximately 20 percent larger than expected for a polar bear.[12] However, re-evaluation in the 21st century has indicated that the fragment likely comes from a giant brown bear.[15][16]

Evolution

The polar bear is one of eight extant species in the bear family Ursidae and of six extant species in the subfamily Ursinae. A possible phylogeny of extant bear species is shown in a cladogram based on complete mitochondrial DNA sequences from Yu et al. (2007)[17] The polar bear and the brown bear form a close grouping, while the relationships of the other species are not very well resolved.[18]

| Ursidae |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

A more recent phylogeny below is based on a 2017 genetic study. The study concludes that Ursine bears originated around 5 million years ago and show extensive hybridization of species in their lineage.[19]

| Ursidae |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Fossils of polar bears are uncommon.[12][15] The oldest known fossil is a 130,000- to 110,000-year-old jaw bone, found on Prince Charles Foreland, Norway, in 2004.[20][1] Scientists in the 20th century surmised that polar bears directly descended from a population of brown bears, possibly in eastern Siberia or Alaska.[12][15] Mitochondrial DNA studies in the 1990s and 2000s supported the status of the polar bear as a derivative of the brown bear, finding that some brown bear populations were more closely related to polar bears than to other brown bears, particularly the ABC Islands bears of Southeast Alaska.[20][21][22] A 2010 study estimated that the polar bear lineage split from other brown bears around 150,000 years ago.[20]

More extensive genetic studies have refuted the idea that polar bears are directly descended from brown bears and found that the two species are separate sister lineages. The genetic similarities between polar bears and some brown bears were found to be the result of interbreeding.[23][24] A 2012 study estimated the split between polar and brown bears as occurring around 600,000 years ago.[23] A 2022 study estimated the divergence as occurring even earlier at over one million years ago.[24] Glaciation events over hundreds of thousands of years led to both the origin of polar bears and their subsequent interactions and hybridizations with brown bears.[25]

Studies in 2011 and 2012 concluded that gene flow went from brown bears to polar bears during hybridization.[23][26] In particular, a 2011 study concluded that living polar bear populations derived their maternal lines from now-extinct Irish brown bears.[26] Later studies have clarified that gene flow went from polar to brown bears rather than the reverse.[25][27][28] Up to 9 percent of the genome of ABC bears was transferred from polar bears,[29] while Irish bears had up to 21.5 percent polar bear origin.[27] Mass hybridization between the two species appears to have stopped around 200,000 years ago. Modern hybrids are relatively rare in the wild.[24]

Analysis of the number of variations of gene copies in polar bears compared with brown bears and American black bears shows distinct adaptions. Polar bears have a less diverse array of olfactory receptor genes, a result of there being fewer odours in their Arctic habitat. With its carnivorous, high-fat diet the species has fewer copies of the gene involved in making amylase, an enzyme that breaks down starch, and more selection for genes for fatty acid breakdown and a more efficient circulatory system. The polar bear's thicker coat is the result of more copies of genes involved in keratin-creating proteins.[30]

Characteristics

The polar bear is the largest living species of bear and land carnivore, though some brown bear subspecies like the Kodiak bear can rival it in size.[31][32] Males are generally 200–250 cm (6.6–8.2 ft) long with a weight of 300–800 kg (660–1,760 lb). Females are smaller at 180–200 cm (5.9–6.6 ft) with a weight of 150–300 kg (330–660 lb).[10] Sexual dimorphism in the species is particularly high compared with most other mammals.[33] Male polar bears also have proportionally larger heads than females.[34] The weight of polar bears fluctuates during the year, as they can bulk up on fat and increase their mass by 50 percent.[31] A fattened, pregnant female can weigh as much as 500 kg (1,100 lb).[35] Adults may stand 130–160 cm (4.3–5.2 ft) tall at the shoulder. The tail is 76–126 mm (3.0–5.0 in) long.[10] The largest polar bear on record, reportedly weighing 1,002 kg (2,209 lb), was a male shot at Kotzebue Sound in northwestern Alaska in 1960.[36]

Compared with the brown bear, this species has a more slender build, with a narrower, flatter and smaller skull, a longer neck, and a lower shoulder hump.[31][37] The snout profile is curved, resembling a "Roman nose".[31] They have 34–42 teeth including 12 incisors, 4 canines, 8–16 premolars and 10 molars. The teeth are adapted for a more carnivorous diet than that of the brown bear, having longer, sharper and more spaced out canines, and smaller, more pointed cheek teeth (premolars and molars).[33][38][37] The species has a large space or diastema between the canines and cheek teeth, which may allow it to better bite into prey.[38][39] Since it normally preys on animals much smaller than it, the polar bear does not have a particularly strong bite.[39] Polar bears have large paws, with the front paws being broader than the back. The feet are hairier than in other bear species, providing warmth and friction when stepping on snow and sea ice.[40] The claws are small but sharp and hooked and are used both to snatch prey and climb onto ice.[41][42]

The coat consists of dense underfur around 5 cm (2.0 in) long and guard hairs around 15 cm (5.9 in) long.[10] Males have long hairs on their forelegs, which is thought to signal their fitness to females.[43] The outer surface of the hairs has a scaly appearance, and the guard hairs are hollow, which allows the animals to trap heat and float in the water.[44] The transparent guard hairs forward scatter ultraviolet light between the underfur and the skin, leading to a cycle of absorption and re-emission, keeping them warm.[45] The fur appears white due to the backscatter of incident light and the absence of pigment.[45][46] Polar bears gain a yellowish colouration as they are exposed more to the sun. This is reversed after they moult. It can also be grayish or brownish.[10] Their light fur provides camouflage in their snowy environment. After emerging from the water, the bear can easily shake itself dry before freezing since the hairs are resistant to tangling when wet.[47] The skin, including the nose and lips, is black and absorbs heat.[10][45] Polar bears have a 5–10 cm (2.0–3.9 in) thick layer of fat underneath the skin,[10] which provides both warmth and energy.[48] Polar bears maintain their core body temperature at about 36.9 °C (98 °F).[49] Overheating is countered by a layer of highly vascularized striated muscle tissue and finely controlled blood vessels. Bears also cool off by entering the water.[45][50]

The eyes of a polar bear are close to the top of the head, which may allow them to stay out of the water when the animal is swimming at the surface. They are relatively small, which may be an adaption against blowing snow and snow blindness. Polar bears are dichromats, and lack the cone cells for seeing green. They have many rod cells which allow them to see at night. The ears are small, allowing them to retain heat and not get frostbitten.[51] They can hear best at frequencies of 11.2–22.5 kHz, a wider frequency range than expected given that their prey mostly makes low-frequency sounds.[52] The nasal concha creates a large surface area, so more warm air can move through the nasal passages.[53] Their olfactory system is also large and adapted for smelling prey over vast distances.[54] The animal has reniculate kidneys which filter out the salt in their food.[55]

Distribution and habitat

Polar bears inhabit the Arctic and adjacent areas. Their range includes Greenland, Canada, Alaska, Russia and the Svalbard Archipelago of Norway.[10][57][58] Polar bears have been recorded 25 km (16 mi) from the North Pole.[59] The southern limits of their range include James Bay and Newfoundland and Labrador in Canada and St. Matthew Island and the Pribilof Islands of Alaska.[10] They are not permanent residents of Iceland but have been recorded visiting there if they can reach it via sea ice.[60] Due to minimal human encroachment on the bears' remote habitat, they can still be found in much of their original range, more so than any other large land carnivore.[61]

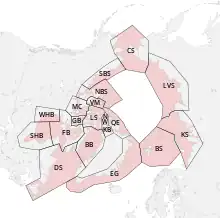

Polar bears have been divided into at least 18 subpopulations labelled East Greenland (ES), Barents Sea (BS), Kara Sea (KS), Laptev Sea (LVS), Chukchi Sea (CS), northern and southern Beaufort Sea (SBS and NBS), Viscount Melville (VM), M'Clintock Channel (MC), Gulf of Boothia (GB), Lancaster Sound (LS), Norwegian Bay (NB), Kane Basin (KB), Baffin Bay (BB), Davis Strait (DS), Foxe Basin (FB) and the western and southern Hudson Bay (WHB and SHB) populations.[62][56] Bears in and around the Queen Elizabeth Islands have been proposed as a subpopulation but this is not universally accepted.[56] A 2022 study has suggested that the bears in southeast Greenland should be considered a different subpopulation based on their geographic isolation and genetics.[63] Polar bear populations can also be divided into four gene clusters: Southern Canadian, Canadian Archipelago, Western Basin (northwestern Canada west to the Russian Far East) and Eastern Basin (Greenland east to Siberia).[62]

The polar bear is dependent enough on the ocean to be considered a marine mammal.[14][64] It is pagophilic and mainly inhabits annual sea ice covering continental shelves and between islands of archipelagos. These areas, known as the "Arctic Ring of Life", have high biological productivity.[61][65] The species tends to frequent areas where sea ice meets water, such as polynyas and leads, to hunt the seals that make up most of its diet.[66] Polar bears travel in response to changes in ice cover throughout the year. They are forced onto land in summer when the sea ice disappears.[67] Terrestrial habitats used by polar bears include forests, mountains, rocky areas, lakeshores and creeks.[68] In the Chukchi and Beaufort seas, where the sea ice breaks off and floats north during the summer, polar bears generally stay on the ice, though a large portion of the population (15–40%) has been observed spending all summer on land since the 1980s.[69] Some areas have thick multiyear ice that does not completely melt and the bears can stay on all year,[70][71] though this type of ice has fewer seals and allows for less productivity in the water.[71]

Behaviour and ecology

Polar bears may travel areas as small as 3,500 km2 (1,400 sq mi) to as large as 38,000 km2 (15,000 sq mi) in a year, while drifting ice allows them to move further.[72] Depending on ice conditions, a bear can travel an average of 12 km (7.5 mi) per day.[73] These movements are powered by their energy-rich diet.[48] Polar bears move by walking and galloping and do not trot.[74] Walking bears tilt their front paws towards each other.[41] They can run at estimated speeds of up to 40 km/h (25 mph)[75] but typically move at around 5.5 km/h (3.4 mph).[76] Polar bears are also capable swimmers and can swim at up to 6 km/h (3.7 mph).[77] One study found they can swim for an average of 3.4 days at a time and travel an average of 154.2 km (95.8 mi).[78] They can dive for as long as three minutes.[79] When swimming, the broad front paws do the paddling, while the hind legs play a role in steering and diving.[10][41]

Most polar bears are active year-round. Hibernation occurs only among pregnant females.[80] Non-hibernating bears typically have a normal 24-hour cycle even during days of all darkness or all sunlight, though cycles less than a day are more common during the former.[81] The species is generally diurnal, being most active early in the day.[82] Polar bears sleep close to eight hours a day on average.[83] They will sleep in various positions, including curled up, sitting up, lying on one side, on the back with limbs spread, or on the belly with the rump elevated.[42][76] On sea ice, polar bears snooze at pressure ridges where they dig on the sheltered side and lie down. After a snowstorm, a bear may rest under the snow for hours or days. On land, the bears may dig a resting spot on gravel or sand beaches.[84] They will also sleep on rocky outcrops.[85] In mountainous areas on the coast, mothers and subadults will sleep on slopes where they can better spot another bear coming.[83] Adult males are less at risk from other bears and can sleep nearly anywhere.[85]

Social life

Polar bears are typically solitary, aside from mothers with cubs and mating pairs.[86] On land, they are found closer together and gather around food resources. Adult males, in particular, are more tolerant of each other in land environments and outside the breeding season.[87][88] They have been recorded forming stable "alliances", travelling, resting and playing together. A dominant hierarchy exists among polar bears with the largest mature males ranking at the top. Adult females outrank subadults and adolescents and younger males outrank females of the same age. In addition, cubs with their mothers outrank those on their own.[89] Females with dependent offspring tend to stay away from males,[88] but are sometimes associated with other female–offspring units, creating "composite families".[89]

Polar bears are generally quiet but can produce various sounds.[90] Chuffing, a soft pulsing call, is made by mother bears presumably to keep in contact with their young.[91] During the breeding season, adult males will chuff at potential mates.[92] Unlike other animals where chuffing is passed through the nostrils, in polar bears it is emitted through a partially open mouth.[91] Cubs will cry for attention and produce humming noises while nursing.[93] Teeth chops, jaw pops, blows, huffs, moans, growls and roars are heard in more hostile encounters.[92] A polar bear visually communicates with its eyes, ears, nose and lips.[89] Chemical communication can also be important: bears secrete their scent from their foot pads into their tracks, allowing individuals to keep track of one another.[94]

Diet and hunting

The polar bear is a hypercarnivore,[95] and the most carnivorous species of bear.[37] It is an apex predator of the Arctic,[96] preying on ice-living seals and consuming their energy-rich blubber.[97] The most commonly taken species is the ringed seal, but they also prey on bearded seals and harp seals.[10] Ringed seals are ideal prey as they are abundant and small enough to be overpowered by even small bears.[98] Bearded seal adults are larger and are more likely to break free from an attacking bear, hence adult male bears are more successful in hunting them. Less common prey are hooded seals, spotted seals, ribbon seals and the more temperate-living harbour seals.[99] Polar bears, mostly adult males, will occasionally hunt walruses, both on land and ice, though they mainly target the young, as adults are too large and formidable, with their thick skin and long tusks.[100]

_with_its_prey.jpg.webp)

Besides seals, bears will prey on cetacean species such as beluga whales and narwhals, as well as reindeer, birds and their eggs, fish and marine invertebrates.[101] They rarely eat plant material as their digestive system is too specialized for animal matter,[102] though they have been recorded eating berries, moss, grass and seaweed.[103] In their southern range, especially near Hudson Bay and James Bay, polar bears endure all summer without sea ice to hunt from and must subsist more on terrestrial foods.[104] Fat reserves allow polar bears to survive for months without eating.[105] Cannibalism is known to occur in the species.[106]

Polar bears hunt their prey in several different ways. When a bear spots a seal hauling out on the sea ice, it slowly stalks it with the head and neck lowered, possibly to make its dark nose and eyes less noticeable. As it gets closer, the bear crouches more and eventually charges at a high speed, attempting to catch the seal before it can escape into its ice hole. Some stalking bears need to move through water; traversing through water cavities in the ice when approaching the seal or swimming towards a seal on an ice floe. The polar bear can stay underwater with its nose exposed. When it gets close enough, the animal lunges from the water to attack.[107]

During a limited time in spring, polar bears will search for ringed seal pups in their birth lairs underneath the ice. Once a bear catches the scent of a hiding pup and pinpoints its location, it approaches the den quietly to not alert it. It uses its front feet to smash through the ice and then pokes its head in to catch the pup before it can escape. A ringed seal's lair can be more than 1 m (3.3 ft) below the surface of the ice and thus more massive bears are better equipped for breaking in. Some bears may simply stay still near a breathing hole or other spot near the water and wait for prey to come by.[108] This can last hours and when a seal surfaces the bear will try to pull it out with its paws and claws.[109] This tactic is the primary hunting method from winter to early spring.[10]

Bears hunt walrus groups by provoking them into stampeding and then look for young that have been crushed or separated from their mothers during the turmoil.[100] There are reports of bears trying to kill or injure walruses by throwing rocks and pieces of ice on them.[110] Belugas and narwhals are vulnerable to bear attacks when they are stranded in shallow water or stuck in isolated breathing holes in the ice.[111] When stalking reindeer, polar bears will hide in vegetation before an ambush.[75] On some occasions, bears may try to catch prey in open water, swimming underneath a seal or aquatic bird. Seals in particular, however, are more agile than bears in the water.[112] Polar bears rely on raw power when trying to kill their prey, and will employ bites and paw swipes.[95] They have the strength to pull a mid-sized seal out of the water or haul a beluga carcass for quite some distance.[113] Polar bears only occasionally store food for later—burying it under snow—and only in the short term.[114]

Arctic foxes routinely follow polar bears and scavenge scraps from their kills. The bears usually tolerate them but will charge a fox that gets too close when they are feeding. Polar bears themselves will scavenge. Subadult bears will eat remains left behind by others. Females with cubs often abandon a carcass when they see an adult male approaching, though are less likely to if they have not eaten in a long time.[115] Whale carcasses are a valuable food source, particularly on land and after the sea ice melts, and attract several bears.[87] In one area in northeastern Alaska, polar bears have been recorded competing with grizzly bears for whale carcasses. Despite their smaller size, grizzlies are more aggressive and polar bears are likely to yield to them in confrontations.[116] Polar bears will also scavenge at garbage dumps during ice-free periods.[117]

Reproduction and development

Polar bear mating takes place on the sea ice and during spring, mostly between March and May.[10][118][119][86] Males search for females in estrus and often travel in twisting paths which reduces the chances of them encountering other males while still allowing them to find females. The movements of females remain linear and they travel more widely.[120] The mating system can be labelled as female-defence polygyny, serial monogamy or promiscuity.[119][121]

Upon finding a female, a male will try to isolate and guard her. Courtship can be somewhat aggressive, and a male will pursue a female if she tries to run away. It can take days for the male to mate with the female which induces ovulation. After their first copulation, the couple bond. Undisturbed polar bear pairings typically last around two weeks during which they will sleep together and mate multiple times.[122] Competition for mates can be intense and this has led to sexual selection for bigger males. Polar bear males often have scars from fighting.[118][119] A male and female that have already bonded will flee together when another male arrives.[123] A female mates with multiple males in a season and a single litter can have more than one father.[121]

When the mating season ends, the female will build up more fat reserves to sustain both herself and her young. Sometime between August and October, the female constructs and enters a maternity den for winter. Depending on the area, maternity dens can be found in sea ice just off the coastline or further inland and may be dug underneath snow, earth or a combination of both.[124] The inside of these shelters can be around 1.5 m (4.9 ft) wide with a ceiling height of 1.2 m (3.9 ft) while the entrance may be 2.1 m (6.9 ft) long and 1.2 m (3.9 ft) wide. The temperature of a den can be much higher than the outside.[125] Females hibernate and give birth to their cubs in the dens.[126] Hibernating bears fast and internally recycle bodily waste. Polar bears experience delayed implantation and the fertilized embryo does not start development until the fall, between mid-September and mid-October.[127] With delayed implantation, gestation in the species lasts seven to nine months but actual pregnancy is only two months.[128]

Mother polar bears typically give birth to two cubs per litter. As with other bear species, newborn polar bears are tiny and altricial.[129] The newborns have woolly hair and pink skin, with a weight of around 600 g (21 oz).[10][31] Their eyes remain closed for a month.[130] The mother's fatty milk fuels their growth, and the cubs are kept warm both by the mother's body heat and the den. The mother emerges from the den between late February and early April, and her cubs are well-developed and capable of walking with her.[131] At this time they weigh 10–15 kilograms (22–33 lb).[10] A polar bear family stays near the den for roughly two weeks; during this time the cubs will move and play around while the mother mostly rests. They eventually head out on the sea ice.[132]

Cubs under a year old stay close to their mother. When she hunts, they stay still and watch until she calls them back.[133] Observing and imitating the mother helps the cubs hone their hunting skills.[134] After their first year they become more independent and explore. At around two years old, they are capable of hunting on their own.[135] The young suckle their mother as she is lying on her side or sitting on her rump.[132] A lactating female cannot conceive and give birth,[136] and cubs are weaned between two and two-and-a-half years.[10] She may simply leave her weaned young or they may be chased away by a courting male.[135] Polar bears reach sexual maturity at around four years for females and six years for males.[137] Females reach their adult size at 4 or 5 years of age while males are fully grown at twice that age.[138]

Mortality

Polar bears can live up to 30 years.[10] The bear's long lifespan and ability to consistently produce young offsets cub deaths in a population. Some cubs die in the dens or the womb if the female is not in good condition. Nevertheless, the female has a chance to produce a surviving litter the next spring if she can eat better in the coming year. Cubs will eventually starve if their mothers cannot kill enough prey.[139] Cubs also face threats from wolves[140] and adult male bears. Males kill cubs to bring their mother back into estrus but also kill young outside the breeding season for food.[106] A female and her cubs can flee from the slower male. If the male can get close to a cub, the mother may try to fight him off, sometimes at the cost of her life.[141]

Subadult bears, who are independent but not quite mature, have a particularly rough time as they are not as successful hunters as adults. Even when they do succeed, their kill will likely be stolen by a larger bear. Hence subadults have to scavenge and are often underweight and at risk of starvation. At adulthood, polar bears have a high survival rate, though adult males suffer injuries from fights over mates.[142] Polar bears are especially susceptible to Trichinella, a parasitic roundworm they contract through cannibalism.[143]

Conservation status

In 2015, the IUCN Red List categorized the polar bear as vulnerable due to a "decline in area of occupancy, extent of occurrence and/or quality of habitat". It estimated the total population to be between 22,000 and 31,000, and the current population trend is unknown. Threats to polar bear populations include climate change, pollution and energy development.[2]

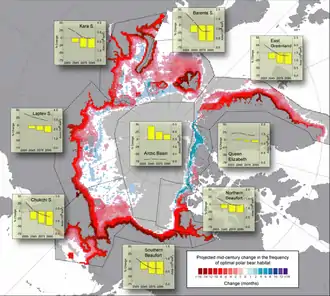

In 2021, the IUCN/SSC Polar Bear Specialist Group labelled four subpopulations (Barents and Chukchi Sea, Foxe Basin and Gulf of Boothia) as "likely stable", two (Kane Basin and M'Clintock Channel) as "likely increased" and three (Southern Beaufort Sea, Southern and Western Hudson Bay) as "likely decreased" over specific periods between the 1980s and 2010s. The remaining ten did not have enough data.[56] A 2008 study predicted two-thirds of the world's polar bears may disappear by 2050, based on the reduction of sea ice, and only one population would likely survive in 50 years.[145] A 2016 study projected a likely decline in polar bear numbers of more than 30 percent over three generations. The study concluded that declines of more than 50 percent are much less likely.[146] A 2012 review suggested that polar bears may become regionally extinct in southern areas by 2050 if trends continue, leaving the Canadian Archipelago and northern Greenland as strongholds.[147]

The key danger from climate change is malnutrition or starvation due to habitat loss. Polar bears hunt seals on the sea ice, and rising temperatures cause the ice to melt earlier in the year, driving the bears to shore before they have built sufficient fat reserves to survive the period of scarce food in the late summer and early fall. Thinner sea ice tends to break more easily, which makes it more difficult for polar bears to access seals. Insufficient nourishment leads to lower reproductive rates in adult females and lower survival rates in cubs and juvenile bears. Lack of access to seals also causes bears to find food on land which increases the risk of conflict with humans.[61][147]

Reduction in sea ice cover also forces bears to swim longer distances, which further depletes their energy stores and occasionally leads to drowning. Increased ice mobility may result in less stable sites for dens or longer distances for mothers travelling to and from dens on land. Thawing of permafrost would lead to more fire-prone roofs for bears denning underground. Less snow may affect insulation while more rain could cause more cave-ins.[61][147] The maximum corticosteroid-binding capacity of corticosteroid-binding globulin in polar bear serum correlates with stress in polar bears, and this has increased with climate warming.[148] Disease-causing bacteria and parasites would flourish more readily in a warmer climate.[147]

Oil and gas development also affects polar bear habitat. The Chukchi Sea Planning Area of northwestern Alaska, which has had many drilling leases, was found to be an important site for non-denning female bears.[149] Oil spills are also a risk. A 2018 study found that ten percent or less of prime bear habitat in the Chukchi Sea is vulnerable to a potential spill, but a spill at full reach could impact nearly 40 percent of the polar bear population.[150] Polar bears accumulate high levels of persistent organic pollutants such as polychlorinated biphenyl (PCBs) and chlorinated pesticides, due to their position at the top of the ecological pyramid. Many of these chemicals have been internationally banned due to the recognition of their harm to the environment. Traces of them have slowly dwindled in polar bears but persist and have even increased in some populations.[151]

Polar bears receive some legal protection in all the countries they inhabit. The species has been labelled as threatened under the US Endangered Species Act since 2008,[152] while the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada listed it as of 'Special concern' since 1991.[153] In 1973, the Agreement on the Conservation of Polar Bears was signed by all five nations with polar bear populations, Canada, Denmark (of which Greenland is an autonomous territory), Russia (then USSR), Norway and the US. This banned most harvesting of polar bears, allowed indigenous hunting using traditional methods, and promoted the preservation of bear habitat.[154] The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna lists the species under Appendix II,[3] which allows regulated trade.[155]

Relationship with humans

Polar bears have coexisted and interacted with circumpolar peoples for millennia.[156] "White bears" are mentioned as commercial items in the Japanese book Nihon Shoki in the seventh century. It is not clear if these were polar bears or white-coloured brown bears.[157] During the Middle Ages, Europeans considered white bears to be a novelty and were more familiar with brown- and black-coloured bears.[158] The first known written account of the polar bear in its natural environment is found in the 13th-century anonymous Norwegian text Konungs skuggsjá, which mentions that "the white bear of Greenland wanders most of the time on the ice of the sea, hunting seals and whales and feeding on them" and says the bear is "as skillful a swimmer as any seal or whale".[159]

_-_Nelson_and_the_Bear_-_BHC2907_-_Royal_Museums_Greenwich.jpg.webp)

Over the next centuries, several European explorers would mention polar bears and describe their habits.[160][161] Such accounts became more accurate after the Enlightenment, and both living and dead specimens were brought back. Nevertheless, some fanciful reports continued, including the idea that polar bears cover their noses during hunts. A relatively accurate drawing of a polar bear is found in Henry Ellis's work A Voyage to Hudson's Bay (1748).[162] Polar bears were formally classified as a species by Constantine Phipps after his 1773 voyage to the Arctic. Accompanying him was a young Horatio Nelson, who was said to have wanted to get a polar bear coat for his father but failed in his hunt.[9] In his 1785 edition of Histoire Naturelle, Comte de Buffon mentions and depicts a "sea bear", clearly a polar bear, and "land bears", likely brown and black bears. This helped promote ideas about speciation. Buffon also mentioned a "white bear of the forest", possibly a Kermode bear.[163]

Exploitation

.jpg.webp)

Polar bears were hunted as early as 8,000 years ago, as indicated by archaeological remains at Zhokhov Island in the East Siberian Sea. The oldest graphic depiction of a polar bear shows it being hunted by a man with three dogs. This rock art was among several petroglyphs found at Pegtymel in Siberia and dates from the fifth to eighth centuries. Before access to firearms, native people used lances, bows and arrows and hunted in groups accompanied by dogs. Though hunting typically took place on foot, some people killed swimming bears from boats with a harpoon. Polar bears were sometimes killed in their dens. Killing a polar bear was considered a rite of passage for boys in some cultures. Native people respected the animal and hunts were subject to strict rituals.[164] Bears were harvested for the fur, meat, fat, tendons, bones and teeth.[165][166] The fur was worn and slept on, while the bones and teeth were made into tools. For the Netsilik, the individual who finally killed the bear had the right to its fur while the meat was passed to all in the party. Some people kept the cubs of slain bears.[167]

Norsemen in Greenland traded polar bear furs in the Middle Ages.[168] Russia traded polar bear products as early as 1556, with Novaya Zemlya and Franz Josef Land being important commercial centres. Large-scale hunting of bears at Svalbard occurred since at least the 18th century, when no less than 150 bears were killed each year by Russian explorers. In the next century, more Norwegians were harvesting the bears on the island. From the 1870s to the 1970s, around 22,000 of the animals were hunted in total. Over 150,000 polar bears in total were either killed or captured in Russia and Svalbard, from the 18th to the 20th century. In the Canadian Arctic, bears were harvested by commercial whalers especially if they could not get enough whales. The Hudson's Bay Company is estimated to have sold 15,000 polar bear coats between the late 19th century and early 20th century.[169] In the mid-20th century, countries began to regulate polar bear harvesting, culminating in the 1973 agreement.[154]

Polar bear meat was commonly eaten as rations by explorers and sailors in the Arctic. Its taste and texture have been described both positively and negatively. Some have called it too coarse with a powerful smell, while others praised it as a "royal dish".[170] The liver was known for being too toxic to eat. This is due to the accumulation of vitamin A from their prey.[171] Polar bear fat was also used in lamps when other fuel was unavailable.[170] Polar bear rugs were almost ubiquitous on the floors of Norwegian churches by the 13th and 14th centuries. In more modern times, classical Hollywood actors would pose on bearskin rugs, notably Marilyn Monroe. Such images often had sexual connotations.[172]

Conflicts

When the sea ice melts, polar bears, particularly subadults, conflict with humans over resources on land.[173] They are attracted to the smell of human-made foods, particularly at garbage dumps and may be shot when they encroach on private property.[174] In Churchill, Manitoba, local authorities maintain a "polar bear jail" where nuisance bears are held until the sea ice freezes again.[175] Climate change has increased conflicts between the two species.[173] Over 50 polar bears swarmed a town in Novaya Zemlya in February 2019, leading local authorities to declare a state of emergency.[176]

From 1870 to 2014, there were an estimated 73 polar bear attacks on humans, which led to 20 deaths. The majority of attacks were by hungry males, typically subadults, while female attacks were usually in defence of the young. In comparison to brown and American black bears, attacks by polar bears were more often near and around where humans lived. This may be due to the bears getting desperate for food and thus more likely to seek out human settlements. As with the other two bear species, polar bears are unlikely to target more than two people at once. Though popularly thought of as the most dangerous bear, the polar bear is no more aggressive to humans than other species.[177]

Captivity

The polar bear was a particularly sought-after species for exotic animal collectors due to being relatively rare and remote living, and its reputation as a ferocious beast.[178] It is one of the few marine mammals that can reproduce well in captivity.[179] They were originally kept only by royals and elites. The Tower of London got a polar bear as early as 1252 under King Henry III. In 1609, James VI and I of Scotland, England and Ireland were given two polar bear cubs by the sailor Jonas Poole, who got them during a trip to Svalbard.[180] At the end of the 17th century, Frederick I of Prussia housed polar bears in menageries with other wild animals. He had their claws and canines removed to perform mock fights. Around 1726, Catherine I of Russia gifted two polar bears to Augustus II the Strong of Poland, who desired them for his animal collection.[181] Later, polar bears were displayed to the public in zoos and circuses.[182] In early 19th century, the species was exhibited at the Exeter Exchange in London, as well as menageries in Vienna and Paris. The first zoo in North America to exhibit a polar bear was the Philadelphia Zoo in 1859.[183]

Polar bear exhibits were innovated by Carl Hagenbeck, who replaced cages and pits with settings that mimicked the animal's natural environment. In 1907, he revealed a complex panoramic structure at the Tierpark Hagenbeck Zoo in Hamburg consisting of exhibits made of artificial snow and ice separated by moats. Different polar animals were displayed on each platform, giving the illusion of them living together. Starting in 1975, Hellabrunn Zoo in Munich housed its polar bears in an exhibit which consisted of a glass barrier, a house, concrete platforms mimicking ice floes and a large pool. Inside the house were maternity dens, and rooms for the staff to prepare and store the food. The exhibit was connected to an outdoor yard for extra room. Similar naturalistic and "immersive" exhibits were opened in the early 21st century, such as the "Arctic Ring of Life" at the Detroit Zoo and Ontario's Cochrane Polar Bear Habitat.[184][185] Many zoos in Europe and North America have stopped keeping polar bears due to the size and costs of their complex exhibits.[186] In North America, the population of polar bears in zoos reached its zenith in 1975 with 229 animals and declined in the 21st century.[187]

Polar bears have been trained to perform in circuses. Bears in general, being large, powerful, easy to train and human-like in form, were widespread in circuses, and the white coat of polar bears made them particularly attractive. Circuses helped change the polar bear's image from a fearsome monster to something more comical. Performing polar bears were used in 1888 by Circus Krone in Germany and later in 1904 by the Bostock and Wombwell Menagerie in England. Circus director Wilhelm Hagenbeck trained up to 75 polar bears to slide into a large tank through a chute. He began performing with them in 1908 and they had a particularly well-received show at the Hippodrome in London. Other circus tricks performed by polar bears involved tightropes, balls, roller skates and motorcycles. One of the most famous polar bear trainers in the second half of the twentieth century was the East German Ursula Böttcher, whose small stature contrasted with that of the large bears. Starting in the late 20th century, most polar bear acts were retired and the use of these bears for the circus is now prohibited in the US.[188]

Several captive polar bears gained celebrity status in the late 20th and early 21st century, notably Knut of the Berlin Zoological Garden, who was rejected by his mother and had to be hand-reared by zookeepers. Another bear, Binky of the Alaska Zoo in Anchorage, became famous for attacking two visitors who got too close.[189][190] Captive polar bears may pace back and forth, a stereotypical behaviour. In one study, they were recorded to have spent 14 percent of their days pacing.[191] Gus of the Central Park Zoo was prescribed Prozac by a therapist for constantly swimming in his pool.[192] To reduce stereotypical behaviours, zookeepers provide the bears with enrichment items to trigger their play behaviour.[193] Zoo polar bears may appear green due to algae concentrations.[194]

Cultural significance

_(3034045389).jpg.webp)

Polar bears have prominent roles in Inuit culture and religion. The deity Torngarsuk is sometimes imagined as a giant polar bear. He resides underneath the sea floor in an underworld of the dead and has power over sea creatures. Kalaallit shamans would worship him through singing and dancing and were expected to be taken by him to the sea and consumed if he considered them worthy. Polar bears were also associated with the goddess Nuliajuk who was responsible for their creation, along with other sea creatures. It is believed that shamans could reach the Moon or the bottom of the ocean by riding on a guardian spirit in the form of a polar bear. Some folklore involves people turning into or disguising themselves as polar bears by donning their skins or the reverse, with polar bears removing their skins. In Inuit astronomy, the Pleiades star cluster is conceived of as a polar bear trapped by dogs while Orion's Belt, the Hyades and Aldebaran represent hunters, dogs and a wounded bear respectively.[195]

Nordic folklore and literature have also featured polar bears. In The Tale of Auðun of the West Fjords, written around 1275, a poor man named Auðun spends all his money on a polar bear in Greenland, but ends up wealthy after giving the bear to the king of Denmark.[196] In the 14th-century manuscript Hauksbók, a man named Odd kills and eats a polar bear that killed his father and brother. In the story of The Grimsey Man and the Bear, a mother bear nurses and rescues a farmer stuck on an ice floe and is repaid with sheep meat. 18th-century Icelandic writings mention the legend of a "polar bear king" known as the bjarndýrakóngur. This beast was depicted as a polar bear with "ruddy cheeks" and a unicorn-like horn, which glows in the dark. The king could understand when humans talk and was considered to be very astute.[197] Two Norwegian fairy tales, "East of the Sun and West of the Moon" and "White-Bear-King-Valemon", involve white bears turning into men and seducing women.[198]

Drawings of polar bears have been featured on maps of the northern regions. Possibly the earliest depictions of a polar bear on a map is the Swedish Carta marina of 1539, which has a white bear on Iceland or "Islandia". A 1544 map of North America includes two polar bears near Quebec. Notable paintings featuring polar bears include François-Auguste Biard's Fighting Polar Bears (1839) and Edwin Landseer's Man Proposes, God Disposes (1864). Polar bears have also been filmed for cinema. An Inuit polar bear hunt was shot for the 1932 documentary Igloo, while the 1974 film The White Dawn filmed a simulated stabbing of a trained bear for a scene. In the film The Big Show (1961), two characters are killed by a circus polar bear. The scenes were shot using animal trainers instead of the actors. In modern literature, polar bears have been characters in both children's fiction, like Hans Beer's Little Polar Bear and the Whales and Sakiasi Qaunaq's The Orphan and the Polar Bear, and fantasy novels, like Philip Pullman's His Dark Materials series. In radio, Mel Blanc provided the vocals for Jack Benny's pet polar bear Carmichael on The Jack Benny Program.[199] The polar bear is featured on flags and coats of arms, like the coat of arms of Greenland, and in many advertisements, notably for Coca-Cola since 1922.[200]

As charismatic megafauna, polar bears have been used to raise awareness of the dangers of climate change. Aurora the polar bear is a giant marionette created by Greenpeace for climate protests.[201] The World Wide Fund for Nature has sold plush polar bears as part of its "Arctic Home" campaign.[202] Photographs of polar bears have been featured in National Geographic and Time magazines, including ones of them standing on ice floes, while the climate change documentary and advocacy film An Inconvenient Truth (2006) includes an animated bear swimming.[201] Automobile manufacturer Nissan used a polar bear in one of its commercials, hugging a man for using an electric car.[203] To make a statement about global warming, in 2009 a Copenhagen ice statue of a polar bear with a bronze skeleton was purposely left to melt in the sun.[204]

See also

- 2011 Svalbard polar bear attack

- International Polar Bear Day

- List of individual bears – includes individual captive polar bears

- Polar Bears International – conservation organization

- Polar Bear Shores – an exhibit featuring polar bears at Sea World in Australia

Notes

References

- 1 2 Ingólfsson, Ólafur; Wiig, Øystein (2009). "Late Pleistocene fossil find in Svalbard: the oldest remains of a polar bear (Ursus maritimus Phipps, 1744) ever discovered". Polar Research. 28 (3): 455–462. doi:10.3402/polar.v28i3.6131.

- 1 2 Wiig, Ø.; Amstrup, S.; Atwood, T.; Laidre, K.; Lunn, N.; Obbard, M.; Regehr, E.; Thiemann, G. (2015). "Ursus maritimus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2015: e.T22823A14871490. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2015-4.RLTS.T22823A14871490.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- 1 2 "Appendices". cites.org. Retrieved 14 January 2022.

- 1 2 Phipps, John (1774). A voyage towards the North Pole undertaken by His Majesty's command, 1773. London: W. Bowyer and J. Nicols, for J. Nourse. p. 185. Archived from the original on 7 July 2017. Retrieved 13 January 2018.

- ↑ Engelhard 2017, pp. 13, 31, 68–69, 122, 253.

- ↑ Engelhard 2017, p. 48.

- ↑ Derocher 2012, p. 1.

- ↑ Fee 2019, p. 48.

- 1 2 Fee 2019, p. 41.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 DeMaster, Douglas P.; Stirling, Ian (8 May 1981). "Ursus maritimus". Mammalian Species (145): 1–7. doi:10.2307/3503828. JSTOR 3503828. OCLC 46381503.

- 1 2 Ellis 2009, p. 67.

- 1 2 3 4 Kurtén, B. (1964). "The evolution of the polar bear, Ursus maritimus Phipps". Acta Zoologica Fennica. 108: 1–30.

- 1 2 Wilson, Don E. (1976). "Cranial variation in polar bears". Bears: Their Biology and Management. 3: 447–453. doi:10.2307/3872793. JSTOR 3872793.

- 1 2 Committee on Taxonomy (October 2014). "List of Marine Mammal Species & Subspecies". The Society for Marine Mammalogy. Archived from the original on 6 January 2015.

- 1 2 3 Harington, C. R. (2008). "The evolution of Arctic marine mammals". Ecological Adapations. 18 (sp2): S23–S40. Bibcode:2008EcoAp..18S..23H. doi:10.1890/06-0624.1. PMID 18494361.

- ↑ Derocher 2012, p. 37.

- ↑ Yu, Li; Li, Yi-Wei; Ryder, Oliver A.; Zhang, Ya-Ping (2007). "Analysis of complete mitochondrial genome sequences increases phylogenetic resolution of bears (Ursidae), a mammalian family that experienced rapid speciation". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 7 (198): 198. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-7-198. PMC 2151078. PMID 17956639.

- ↑ Servheen, C.; Herrero, S.; Peyton, B. (1999). Bears: Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan (PDF). IUCN. pp. 26–30. ISBN 978-2-8317-0462-3. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ↑ Kumar, V.; Lammers, F.; Bidon, T.; Pfenninger, M.; Kolter, L.; Nilsson, M. A.; Janke, A. (2017). "The evolutionary history of bears is characterized by gene flow across species". Scientific Reports. 7: 46487. Bibcode:2017NatSR...746487K. doi:10.1038/srep46487. PMC 5395953. PMID 28422140.

- 1 2 3 Lindqvist, C.; Schuster, S. C.; Sun, Y.; Talbot, S. L.; Qi, J.; Ratan, A.; Tomsho, L. P.; Kasson, L.; Zeyl, E.; Aars, J.; Miller, W.; Ingolfsson, O.; Bachmann, L.; Wiig, O. (2010). "Complete mitochondrial genome of a Pleistocene jawbone unveils the origin of polar bear". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 107 (11): 5053–5057. Bibcode:2010PNAS..107.5053L. doi:10.1073/pnas.0914266107. PMC 2841953. PMID 20194737.

- ↑ Talbot, S. L.; Shields, G. F. (1996). "Phylogeography of brown bears (Ursus arctos) of Alaska and paraphyly within the Ursidae". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 5 (3): 477–494. doi:10.1006/mpev.1996.0044. PMID 8744762.

- ↑ Shields, G. F.; Adams, D.; Garner, G.; Labelle, M.; Pietsch, J.; Ramsay, M.; Schwartz, C.; Titus, K.; Williamson, S. (2000). "Phylogeography of mitochondrial DNA variation in brown bears and polar bears". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 15 (2): 19–26. doi:10.1006/mpev.1999.0730. PMID 10837161.

- 1 2 3 Hailer, F.; Kutschera, V. E.; Hallstrom, B. M.; Klassert, D.; Fain, S. R.; Leonard, J. A.; Arnason, U.; Janke, A. (2012). "Nuclear genomic sequences reveal that polar bears are an old and distinct bear lineage". Science. 336 (6079): 344–347. Bibcode:2012Sci...336..344H. doi:10.1126/science.1216424. hdl:10261/58578. PMID 22517859. S2CID 12671275.

- 1 2 3 Lan, T.; Leppälä, K.; Tomlin, C.; Talbot, S. L.; Sage, G. K.; Farley, S. D.; Shideler, R. T.; Bachmann, L.; Wiig, Ø; Albert, V. A.; Salojärvi, J.; Mailund, T.; Drautz-Moses, D. I.; Schuster, S. C.; Herrera-Estrella, L.; Lindqvist, C. (2022). "Insights into bear evolution from a Pleistocene polar bear genome". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 119 (14): e2200016119. Bibcode:2022PNAS..11900016L. doi:10.1073/pnas.2200016119. PMC 9214488. PMID 35666863.

- 1 2 Hassanin, A. (2015). "The role of Pleistocene glaciations in shaping the evolution of polar and brown bears. Evidence from a critical review of mitochondrial and nuclear genome analyses" (PDF). Comptes Rendus Biologies. 338 (7): 494–501. doi:10.1016/j.crvi.2015.04.008. PMID 26026577.

- 1 2 Edwards, C. J.; Suchard, M. A.; Lemey, P.; Welch, J. J.; Barnes, I.; Fulton, T. L.; Barnett, R.; O'Connell, T.; Coxon, P.; Monaghan, N.; Valdiosera, C. E.; Lorenzen, E. D.; Willerslev, E.; Baryshnikov, G. F.; Rambaut, A.; Thomas, M. G.; Bradley, D. G.; Shapiro, B. (2011). "Ancient hybridization and an Irish origin for the modern polar bear matriline". Current Biology. 21 (15): 1251–1258. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2011.05.058. PMC 4677796. PMID 21737280.

- 1 2 Cahill, J. A.; Heintzman, P. D.; Harris, K.; Teasdale, M. D.; Kapp, M. D.; Soares, A. E. R.; Stirling, I.; Bradley, D.; Edward, C. J.; Graim, K.; Kisleika, A. A.; Malev, A. V.; Monaghan, N.; Green, R. E.; Shapiro, B. (2018). "Genomic evidence of widespread admixture from polar bears into brown bears during the last ice age". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 35 (5): 1120–1129. doi:10.1093/molbev/msy018. hdl:10037/19512. PMID 29471451.

- ↑ Wang, M-S; Murray, G. G. R.; Mann, D.; Groves, P.; Vershinina, A. O.; Supple, M. A.; Kapp, J. D.; Corbett-Detig, R.; Crump, S. E.; Stirling, I.; Laidre, K. L.; Kunz, M.; Dalén, L.; Green, R. E.; Shapiro, B. (2022). "A polar bear paleogenome reveals extensive ancient gene flow from polar bears into brown bears". Nature Ecology & Evolution. 6 (7): 936–944. Bibcode:2022NatEE...6..936W. doi:10.1038/s41559-022-01753-8. PMID 35711062. S2CID 249747066.

- ↑ Cahill, J. A.; Stirling, I.; Kistler, L.; Salamzade, R.; Ersmark, E.; Fulton, T. L.; Stiller, M.; Green, R. E.; Shapiro, B. (2015). "Genomic evidence of geographically widespread effect of gene flow from polar bears into brown bears". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 24 (6): 1205–1217. Bibcode:2015MolEc..24.1205C. doi:10.1111/mec.13038. PMC 4409089. PMID 25490862.

- ↑ Rink, D. C.; Specian, N. K.; Zhao, S.; Gibbons, J. G. (2019). "Polar bear evolution is marked by rapid changes in gene copy number in response to dietary shift". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 116 (27): 13446–13451. Bibcode:2019PNAS..11613446R. doi:10.1073/pnas.1901093116. PMC 6613075. PMID 31209046.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Derocher 2012, p. 10.

- ↑ Ellis 2009, p. 74.

- 1 2 Ellis 2009, p. 75.

- ↑ Ellis 2009, p. 80.

- ↑ Stirling 2011, p. 38.

- ↑ Wood, G. L. (1983). The Guinness Book of Animal Records. Guinness Superlatives. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-85112-235-9.

- 1 2 3 Slater, G. J.; Figueirido, B.; Louis, L.; Yang, P.; Van Valkenburgh, B. (2010). "Biomechanical consequences of rapid evolution in the polar bear lineage". PLOS ONE. 5 (11): e13870. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...513870S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0013870. PMC 2974639. PMID 21079768.

- 1 2 Derocher 2012, p. 17.

- 1 2 Figueirido, B.; Palmqvist, P.; Pérez-Claros, J. A. (2009). "Ecomorphological correlates of craniodental variation in bears and paleobiological implications for extinct taxa: an approach based on geometric morphometrics". Journal of Zoology. 277 (1): 70–80. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2008.00511.x.

- ↑ Derocher 2012, p. 22.

- 1 2 3 Derocher 2012, p. 21.

- 1 2 Ellis 2009, p. 79.

- ↑ Derocher, Andrew E.; Andersen, Magnus; Wiig, Øystein (2005). "Sexual dimorphism of polar bears". Journal of Mammalogy. 86 (5): 895–901. doi:10.1644/1545-1542(2005)86[895:SDOPB]2.0.CO;2. JSTOR 4094434.

- ↑ Derocher 2012, pp. 7–8.

- 1 2 3 4 Khattab, M. Q.; Tributsch, H. (2015). "Fibre-optical light scattering technology in polar bear hair: A re-evaluation and new results". Journal of Advanced Biotechnology and Bioengineering. 3 (2): 38–51. doi:10.12970/2311-1755.2015.03.02.2.

- ↑ Derocher 2012, p. 7.

- ↑ Ellis 2009, pp. 65, 72.

- 1 2 Derocher 2012, p. 12.

- ↑ Best, R. C. (1982). "Thermoregulation in resting and active polar bears". Journal of Comparative Physiology A. 146: 63–73. doi:10.1007/BF00688718. S2CID 36351845.

- ↑ Tributsch, H.; Goslowsky, H.; Küppers, U.; Wetzel, H. (1990). "Light collection and solar sensing through the polar bear pelt". Solar Energy Materials. 21 (2–3): 219–236. doi:10.1016/0165-1633(90)90056-7.

- ↑ Derocher 2012, pp. 14, 16, 18–19.

- ↑ Nachtigall, P. E.; Supin, A. Y.; Amundin, M.; Röken, B.; Møller, T.; Mooney, T. A.; Taylor, K. A.; Yuen, M. (2007). "Polar bear Ursus maritimus hearing measured with auditory evoked potentials". Journal of Experimental Biology. 210 (7): 1116–1122. doi:10.1242/jeb.02734. PMID 17371910. S2CID 18046149.

- ↑ Derocher 2012, p. 14.

- ↑ Green, P. A.; Van Valkenburgh, B.; Pang, B.; Bird, B.; Rowe, T.; Curtis, A. (2012). "Respiratory and olfactory turbinal size in canid and arctoid carnivorans". Journal of Anatomy. 221 (6): 609–621. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7580.2012.01570.x. PMC 3512284. PMID 23035637.

- ↑ Derocher 2012, p. 26.

- 1 2 3 4 Status Report on the World's Polar Bear Subpopulations: July 2021 Status Report (PDF) (Report). IUCN/SSC Polar Bear Specialist Group. July 2021. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ↑ Ellis 2009, pp. 73, 140.

- ↑ Derocher 2012, p. 3.

- ↑ van Meurs, R.; Splettstoesser, J. F. (1993). "Letter to the editor: farthest north polar bear". Arctic. 56 (3): 309. doi:10.14430/arctic626.

- ↑ Ellis 2009, pp. 122–124.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Derocher, Andrew E.; Lunn, Nicholas J.; Stirling, Ian (2004). "Polar bears in a warming climate". Integrative and Comparative Biology. 44 (2): 163–176. doi:10.1093/icb/44.2.163. PMID 21680496.

- 1 2 Peacock, E.; Sonsthagen, S. A.; Obbard, M. E.; Boltunov, A.; Regehr, E. V.; Ovsyanikov, N.; Aars, J.; Atkinson, S. N.; Sage, G. K.; Hope, A. G.; Zeyl, E.; Bachmann, L.; Ehrich, D.; Scribner, K. T.; Amstrup, S. C.; Belikov, S.; Born, E. W.; Derocher, A. E.; Stirling, I.; Taylor, M. K.; Wiig, Ø; Paetkau, D.; Talbot, S. L. (2015). "Implications of the circumpolar genetic structure of polar bears for their conservation in a rapidly warming Arctic". PLOS ONE. 10 (1): e112021. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..10k2021P. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0112021. PMC 4285400. PMID 25562525.

- ↑ Laidre, K. L.; Supple, M. A.; Born, E. W.; Regehr, E. V.; Wiig, Ø; Ugarte, F.; Aars, J.; Dietz, R.; Sonne, C.; Hegelund, P.; Isaksen, C.; Akse, G. B.; Cohen, B.; Stern, H. L.; Moon, T.; Vollmers, C.; Corbett-Detig, R.; Paetkau, D.; Shapiro, B. (2022). "Glacial ice supports a distinct and undocumented polar bear subpopulation persisting in late 21st-century sea-ice conditions". Science. 376 (6599): 1333–1338. Bibcode:2022Sci...376.1333L. doi:10.1126/science.abk2793. PMID 35709290. S2CID 249746650.

- ↑ Stirling 2011, p. XIII.

- ↑ Stirling 2011, pp. 9–10.

- ↑ Stirling, Ian (1997). "The importance of polynyas, ice edges, and leads to marine mammals and birds". Journal of Marine Systems. 10 (1–4): 9–21. Bibcode:1997JMS....10....9S. doi:10.1016/S0924-7963(96)00054-1.

- ↑ Stirling 2011, p. 9.

- ↑ Derocher 2012, pp. 67–68.

- ↑ Rode, Karyn D.; Douglas, D. C.; Atwood, T. C.; Durner, G. M.; Wilson, R. R.; Pagano, A. M. (December 2022). "Observed and forecasted changes in land use by polar bears in the Beaufort and Chukchi Seas, 1985–2040". Global Ecology and Conservation. 40: e02319. doi:10.1016/j.gecco.2022.e02319.

- ↑ Vongraven, D.; Aars, J.; Amstrup, S.; Atkinson, S. N.; Belikov, S.; Born, E. W.; DeBruyn, T. D.; Derocher, A. E.; Durner, G.; Gill, M.; Lunn, N.; Obbard, M. E.; Omelak, J.; Ovsyanikov, N.; Peacock, E.; Richardson, E.; Sahanatien, V.; Stirling, I.; Wiig, Ø (2012). "A circumpolar monitoring framework for polar bears". Ursus: Monograph Series Number 5. 23: 1–66. doi:10.2192/URSUS-D-11-00026.1. S2CID 67812839.

- 1 2 Stirling 2011, p. 4.

- ↑ Auger-Méthé, M.; Lewis, M. A.; Derocher, A. E. (2016). "Home ranges in moving habitats: polar bears and sea ice". Ecography. 32 (1): 26–35. Bibcode:2016Ecogr..39...26A. doi:10.1111/ecog.01260.

- ↑ Ferguson, S. H.; Taylor, M. K.; Born, E. W.; Rosing-Asvid, A.; Messier, F. (2001). "Activity and movement patterns of polar bears inhabiting consolidated versus active pack ice". Arctic. 54 (1): 49–54. doi:10.14430/arctic763.

- ↑ Gasc, J-P; Abourachid, A (1997). "Kinematic analysis of the locomotion of the polar bear (Ursus maritimus, Phipps, 1774) in natural and experimental conditions". Netherlands Journal of Zoology. 48 (2): 145–167. doi:10.1163/156854298X00156.

- 1 2 Brook, R. K.; Richardson, E. S. (2002). "Observations of polar bear predatory behaviour toward caribou". Arctic. 55 (2): 193–196. doi:10.14430/arctic703.

- 1 2 Stirling 2011, p. 140.

- ↑ Ellis 2009, p. 88.

- ↑ Pagano, A. M.; Durner, G M.; Amstrup, S. C.; Simac, K. S.; York, G. S. (2012). "Long-distance swimming by polar bears (Ursus maritimus) of the southern Beaufort Sea during years of extensive open water". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 90 (5): 663–676. doi:10.1139/Z2012-033.

- ↑ Stirling, Ian; van Meurs, Rinie (2015). "Longest recorded underwater dive by a polar bear". Polar Biology. 38 (8): 1301–1304. Bibcode:2015PoBio..38.1301S. doi:10.1007/s00300-015-1684-1. S2CID 6385494.

- ↑ Derocher 2012, p. 28.

- ↑ Ware, J. V.; Rode, K. D.; Robbins, C. T.; Leise, T.; Weil, C. R.; Jansen, H. T. (2020). "The clock keeps ticking: circadian rhythms of free-ranging polar bears". Journal of Biological Rhythms. 35 (2): 180–194. doi:10.1177/0748730419900877. PMID 31975640. S2CID 210882454.

- ↑ Stirling, I. (1974). "Midsummer observations on the behavior of wild polar bears (Ursus maritimus)". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 52 (9): 1191–1198. doi:10.1139/z74-157.

- 1 2 Stirling 2011, p. 141.

- ↑ Stirling 2011, pp. 140–141.

- 1 2 Derocher 2012, p. 68.

- 1 2 Stirling 2011, p. 105.

- 1 2 Derocher, A. E.; Stirling, I. (1990). "Observations of aggregating behaviour in adult male polar bears (Ursus maritimus)". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 68 (7): 1390–1394. doi:10.1139/z90-207.

- 1 2 Ferguson, S. H.; Taylor, M. K.; Messier, F. (1997). "Space use by polar bears in and around Auyuittuq National Park, Northwest Territories, during the ice-free period". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 75 (10): 1585–1594. doi:10.1139/z97-785.

- 1 2 3 Ovsyanikov, N. G. (2005). "Behavior of polar bears in coastal congregations" (PDF). Zoologicheskiĭ Zhurnal. 84 (1): 94–103.

- ↑ Derocher 2012, p. 30.

- 1 2 Wemmer, C.; Von Ebers, M.; Scow, K. (1976). "An analysis of the chuffing vocalization in the polar bear (Ursus maritimus)". Journal of Zoology. 180 (3): 425–439. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1976.tb04686.x.

- 1 2 Derocher 2012, p. 31.

- ↑ Derocher, A. E.; Van Parijs, S. M.; Wiig, Ø (2010). "Nursing vocalization of a polar bear cub". Ursus. 21 (2): 189–191. doi:10.2192/09SC025.1. S2CID 55599722.

- ↑ Owen, M. A.; Swaisgood, R. R.; Slocomb, C.; Amstrup, S. C.; Durner, G. M.; Simac, K.; Pessier, A. P. (2014). "An experimental investigation of chemical communication in the polar bear". Journal of Zoology. 295 (1): 36–43. doi:10.1111/jzo.12181.

- 1 2 Sacco, T.; Van Valkenburgh, B. (2004). "Ecomorphological indicators of feeding behaviour in the bears (Carnivora: Ursidae)". Journal of Zoology. 263 (1): 41–54. doi:10.1017/S0952836904004856.

- ↑ Stirling 2011, p. 155.

- ↑ Derocher 2012, p. 69.

- ↑ Stirling 2011, pp. 155–156.

- ↑ Derocher 2012, pp. 73, 76–77.

- 1 2 Stirling 2011, p. 161.

- ↑ Derocher 2012, pp. 80–88.

- ↑ Ramsay, M. A.; Hobson, K. A. (May 1991). "Polar bears make little use of terrestrial food webs: evidence from stable-carbon isotope analysis". Oecologia. 86 (4): 598–600. Bibcode:1991Oecol..86..598R. doi:10.1007/BF00318328. PMID 28313343. S2CID 32221744.

- ↑ Derocher 2012, pp. 88–89.

- ↑ Russell, Richard H. (1975). "The food habits of polar bears of James Bay and Southwest Hudson Bay in summer and autumn". Arctic. 28 (2): 117–129. doi:10.14430/arctic2823.

- ↑ Ellis 2009, p. 89.

- 1 2 Taylor, M.; Larsen, T.; Schweinsburg, R. E. (1985). "Observations of intraspecific aggression and cannibalism in polar bears (Ursus maritimus)". Arctic. 38 (4): 303–309. doi:10.14430/arctic2149.

- ↑ Stirling 2011, pp. 170–171.

- ↑ Derocher 2012, pp. 127–129, 131.

- ↑ Ellis 2009, p. 91.

- ↑ Stirling, I.; Laidre, K. L.; Born, E. W. (2021). "Do wild polar bears (Ursus maritimus) use tools when hunting walruses (Odobenus rosmarus)?". Arctic. 74 (2): 175–187. doi:10.14430/arctic72532. S2CID 236227117.

- ↑ Derocher 2012, pp. 80–83.

- ↑ Derocher 2012, pp. 84–85, 132.

- ↑ Ellis 2009, p. 112.

- ↑ Stirling, I.; Laidre, K. L.; Derocher, A. E.; Van Meurs, R. (2020). "The ecological and behavioral significance of short-term food caching in polar bears (Ursus maritimus)". Arctic Science. 6 (1): 41–52. doi:10.1139/as-2019-0008. S2CID 209575444.

- ↑ Stirling 2011, pp. 191–193.

- ↑ Miller, S.; Wilder, J.; Wilson, R. R. (2015). "Polar bear–grizzly bear interactions during the autumn open-water period in Alaska". Journal of Mammalogy. 96 (6): 1317–1325. doi:10.1093/jmammal/gyv140.

- ↑ Lunn, N. J.; Stirling, I. (1985). "The significance of supplemental food to polar bears during the ice-free period of Hudson Bay". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 63 (10): 2291–2297. doi:10.1139/z85-340.

- 1 2 Ramsay, M. A.; Stirling, I. (1986). "On the mating system of polar bears". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 64 (10): 2142–2151. doi:10.1139/z86-329.

- 1 2 3 Derocher, A. E.; Anderson, M.; Wiig, Ø; Aars, J. (2010). "Sexual dimorphism and the mating ecology of polar bears (Ursus maritimus) at Svalbard (Ursus maritimus) at Svalbard". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 64 (6): 939–946. doi:10.1007/s00265-010-0909-0. S2CID 36614970.

- ↑ Laidre, K. L.; Born, E. W.; Gurarie, E.; Wiig, Ø; Dietz, R.; Stern, H. (2013). "Females roam while males patrol: divergence in breeding season movements of pack-ice polar bears (Ursus maritimus)". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 280 (1752): 20122371. doi:10.1098/rspb.2012.2371. PMC 3574305. PMID 23222446.

- 1 2 Zeyl, E.; Aars, J.; Ehrich, D.; Bachmann, L.; Wiig, Ø (2009). "The mating system of polar bears: a genetic approach". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 87 (12): 1195–1209. doi:10.1139/Z09-107.

- ↑ Derocher 2012, pp. 141, 145–147.

- ↑ Derocher 2012, pp. 145–147.

- ↑ Stirling 2011, pp. 112, 115, 120.

- ↑ Ellis 2009, p. 85.

- ↑ Derocher 2012, pp. 28, 155.

- ↑ Stirling 2011, p. 124.

- ↑ Derocher 2012, p. 171.

- ↑ Stirling 2011, pp. 124–125, 131.

- ↑ Ellis 2009, p. 84.

- ↑ Stirling 2011, pp. 126–127.

- 1 2 Stirling 2011, p. 128.

- ↑ Derocher 2012, pp. 173, 184.

- ↑ Stirling 2011, p. 186.

- 1 2 Derocher 2012, p. 184.

- ↑ Derocher 2012, p. 181.

- ↑ Stirling 2011, pp. 128–129.

- ↑ Derocher 2012, p. 185.

- ↑ Stirling 2011, pp. 204–207.

- ↑ Richardson, E. S.; Andriashek, D. (2006). "Wolf (Canis lupus) predation of a polar bear (Ursus maritimus) cub on the sea ice off northwestern Banks Island, Northwest Territories, Canada". Arctic. 59 (3): 322–324. doi:10.14430/arctic318.

- ↑ Stirling 2011, p. 212.

- ↑ Stirling 2011, pp. 207–208.

- ↑ Larsen, Thor; Kjos-Hanssen, Bjørn (1983). "Trichinella sp. in polar bears from Svalbard, in relation to hide length and age". Polar Research. 1 (1): 89–96. Bibcode:1983PolRe...1...89L. doi:10.1111/j.1751-8369.1983.tb00734.x. S2CID 208525641.

- ↑ Durner, George M.; Douglas, David C; Nielson, Ryan M; Amstrup, Steven C; McDonald, Trent L (2007). Predicting the Future Distribution of Polar Bear Habitat in the Polar Basin from Resource Selection Functions Applied to 21st Century General Circulation Model Projections of Sea Ice (PDF) (Report). USGS. Retrieved 20 September 2023.

- ↑ Amstrup, S. C.; Marcot, B. G.; Douglas, D. C. (2008). "A Bayesian network modeling approach to forecasting the 21st century worldwide status of polar bears". Geophysical Monograph Series. 180: 213–268. Bibcode:2008GMS...180..213A. doi:10.1029/180GM14. ISBN 9781118666470.

- ↑ Regehr, E. V.; Laidre, K. L.; Akçakaya, H. R.; Amstrup, S. C.; Atwood, T. C.; Lunn, N. J.; Obbard, M.; Stern, H.; Thiemann, G. W.; Wiig, Ø (2016). "Conservation status of polar bears (Ursus maritimus) in relation to projected sea-ice declines". Biology Letters. 12 (12): 20160556. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2016.0556. PMC 5206583. PMID 27928000.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Stirling, I.; Derocher, A. E. (2012). "Effects of climate warming on polar bears: a review of the evidence". Global Change Biology. 18 (9): 2694–2706. Bibcode:2012GCBio..18.2694S. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2486.2012.02753.x. PMID 24501049. S2CID 205294317.

- ↑ Boonstra, R.; Bodner, K.; Bosson, C.; Delehanty, B.; Richardson, E. S.; Lunn, N. J.; Derocher, A. E.; Molnár, P. K. (2020). "The stress of Arctic warming on polar bears". Global Change Biology. 26 (8): 4197–4214. Bibcode:2020GCBio..26.4197B. doi:10.1111/gcb.15142. PMID 32364624. S2CID 218492928.

- ↑ Wilson, R. R.; Horne, J. S.; Rode, K. D.; Regher, E. V.; Durner, G. M. (2014). "Identifying polar bear resource selection patterns to inform offshore development in a dynamic and changing Arctic". Ecosphere. 5 (10): 1–24. Bibcode:2014Ecosp...5..136W. doi:10.1890/ES14-00193.1.

- ↑ Wilson, R. R.; Perham, C.; French-McCay, D. P.; Balouskus, R. (2018). "Potential impacts of offshore oil spills on polar bears in the Chukchi Sea". Environmental Pollution. 235: 652–659. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2017.12.057. PMID 29339335.

- ↑ Routti, H.; Atwood, T.; Bechshoft, T.; Boltunov, A.; Ciesielski, T. M.; Desforges, J-P; Dietz, R.; Gabrielsen, G. W.; Jenssen, B. M.; Letcher, R. J.; McKinney, M. A.; Morris, A. D.; Rigét, F. F.; Sonne, C.; Styrishave, B.; Tartu, S. (2019). "State of knowledge on current exposure, fate and potential health effects of contaminants in polar bears from the circumpolar Arctic". Science of the Total Environment. 664: 1063–1083. Bibcode:2019ScTEn.664.1063R. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.02.030. PMID 30901781. S2CID 85457329.

- ↑ "Polar Bear Interaction Guidelines". U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ↑ "COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the Polar Bear (Ursus maritimus) in Canada 2018". Government of Canada. 25 November 2019. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- 1 2 Prestrud, P.; Stirling, I. (1994). "The International Polar Bear Agreement and the current status of polar bear conservation". Aquatic Mammals. 20 (3): 113–124.

- ↑ "How CITES works". CITES.org. Retrieved 29 July 2023.

- ↑ Fee 2019, pp. 25–26.

- ↑ Engelhard 2017, p. 30.

- ↑ Ellis 2009, pp. 13.

- ↑ Engelhard 2017, p. 53.

- ↑ Engelhard 2017, pp. 53–66.

- ↑ Ellis 2009, pp. 14–23.

- ↑ Engelhard 2017, pp. 49, 51–52.

- ↑ Engelhard 2017, p. 50.

- ↑ Engelhard 2017, pp. 122–124, 130, 133.

- ↑ Fee 2019, p. 28.

- ↑ Engelhard 2017, p. 128.

- ↑ Engelhard 2017, pp. 127–128, 132.

- ↑ Engelhard 2017, pp. 34–35.

- ↑ Stirling 2011, pp. 246–249.

- 1 2 Engelhard 2017, p. 141.

- ↑ Derocher 2012, p. 27.

- ↑ Fee 2019, pp. 32, 131–133.

- 1 2 Heemskerk, S.; Johnson, A. C.; Hedman, D.; Trim, V.; Lunn, N. J.; McGeachy, D.; Derocher, A. E. (2020). "Temporal dynamics of human-polar bear conflicts in Churchill, Manitoba". Global Ecology and Conservation. 24: e01320. doi:10.1016/j.gecco.2020.e01320. S2CID 225123070.

- ↑ Clark, D. A.; van Beest, F. M.; Brook, R. K. (2012). "Polar Bear-human conflicts: state of knowledge and research needs". Canadian Wildlife Biology and Management. 1 (1): 21–29.

- ↑ Raypole, Crystal (13 May 2023). "Inside Canada's polar bear 'jail' where bears go without food and are kept behind bars — but it's not what you might think". Business Insider. Retrieved 3 September 2023.

- ↑ Stanley-Becker, Isaac (11 February 2019). "A 'mass invasion' of polar bears is terrorizing an island town. Climate change is to blame". washingtonpost.com. washingtonpost. Retrieved 14 February 2019.

- ↑ Wilder, J. M.; Vongraven, D.; Atwood, T.; Hansen, B.; Jessen, A.; Kochnev, A.; York, G.; Vallender, R.; Hedman, D.; Gibbons, M. (2017). "Polar bear attacks on humans: implications of a changing climate". Wildlife Society Bulletin. 41 (3): 537−547. Bibcode:2017WSBu...41..537W. doi:10.1002/wsb.783.

- ↑ Engelhard 2017, pp. 96.

- ↑ Robeck, T. R.; O'Brien, J. K.; Obell, D. K. (2009). "Captive Breeding". In Perrin, William F.; Wursig, Bernd; Thewissen, J. G. M. 'Hans' (eds.). Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals. Academic Press. p. 178. ISBN 978-0-08-091993-5.

- ↑ Fee 2019, pp. 32, 103, 105.

- ↑ Engelhard 2017, pp. 95.

- ↑ Fee 2019, pp. 103, 108.

- ↑ Engelhard 2017, pp. xii, 96–97.

- ↑ Engelhard 2017, pp. 7, 101, 105–106.

- ↑ Fee 2019, p. 118.

- ↑ Fee 2019, pp. 120–121.

- ↑ Curry, E; Safay, S; Meyerson, R; Roth, T. L. (2015). "Reproductive trends of captive polar bears in North American zoos: a historical analysis". Journal of Zoo and Aquarium Research. 3 (3): 99–106. doi:10.19227/jzar.v3i3.133.

- ↑ Engelhard 2017, pp. 109–111, 116–119.

- ↑ Engelhard 2017, pp. 21–24, 105.

- ↑ Fee 2019, pp. 123–124, 145.

- ↑ Shepherdson, D.; Lewis, K. D.; Carlstead, K.; Bauman, J.; Perrin, N. (2013). "Individual and environmental factors associated with stereotypic behavior and fecal glucocorticoid metabolite levels in zoo housed polar bears". Applied Animal Behaviour Science. 147 (3–4): 268–277. doi:10.1016/j.applanim.2013.01.001.

- ↑ Engelhard 2017, p. 24.

- ↑ Canino, W.; Powell, D. (2010). "Formal behavioral evaluation of enrichment programs on a zookeeper's schedule: a case study with a polar bear (Ursus maritimus) at the Bronx Zoo". Zoo Biology. 29 (4): 503–508. doi:10.1002/zoo.20247. PMID 19373879.

- ↑ Lewin, R. A.; Farnsworth, P. A.; Yamanaka, G. (1981). "The algae of green polar bears". Phycologia. 20 (3): 303–314. Bibcode:1981Phyco..20..303L. doi:10.2216/i0031-8884-20-3-303.1.

- ↑ Engelhard 2017, pp. 152–153, 156–162.

- ↑ Fee 2019, p. 32.

- ↑ Engelhard 2017, pp. 165–166, 181–182.

- ↑ Fee 2019, p. 98.

- ↑ Engelhard 2017, pp. xi–xii, 36, 82–83, 100, 116, 184, 215.

- ↑ Fee 2019, pp. 32, 133–135.

- 1 2 Born, D. (2019). "Bearing witness? Polar bears as icons for climate change communication in National Geographic". Environmental Communication. 13 (5): 649–663. Bibcode:2019Ecomm..13..649B. doi:10.1080/17524032.2018.1435557. S2CID 150289699.

- ↑ Dunaway, F (2009). "Seeing global warming: contemporary art and the fate of the planet". Environmental History. 14 (1): 9–31. doi:10.1093/envhis/14.1.9.

- ↑ Martinez, D. E. (2014). "Polar bears, Inuit names, and climate citizenship". In Crow, Deserai A.; Boykoff, Maxwell T (eds.). Culture, Politics and Climate Change In 2009. Taylor & Francis. p. 46. ISBN 9781135103347.

- ↑ Engelhard 2017, p. xiii.

Bibliography

- Derocher, Andrew E. (2012). Polar Bears: A Complete Guide to Their Biology and Behavior. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-1-4214-0305-2.

- Ellis, Richard (2009). On Thin Ice: The Changing World of the Polar Bear. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-307-27059-7.

- Engelhard, Richard (2017). Ice Bear: The Cultural History of an Arctic Icon. University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-99922-7.

- Fee, Margrey (2019). Polar Bear. Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1-78914-146-7.

- Stirling, Ian (2011). Polar Bears: Natural History of a Threatened Species. Fitzhenry and Whiteside. ISBN 978-1-55455-155-2.