| |

| Latin: Universitas Tociensis | |

| Motto | 志ある卓越。 |

|---|---|

Motto in English | Discover Excellence. |

| Type | research university |

| Established | April 12, 1877 |

Academic affiliations | IARU AEARU AGS BESETOHA AALAU |

| Budget | 280 billion JPY (US$2.54 billion) (2021)[1] |

| President | Teruo Fujii |

Academic staff | 3,937 full-time (2022)[2] |

Total staff | 11,487 |

| Students | 28,133 (2022)[3] excluding research students and auditors |

| Undergraduates | 13,962 (2022)[4] |

| Postgraduates | 14,171 (2022)[5] including Professional degree courses |

| Location | , , |

| Campus | Urban |

| Colours | Light Blue |

| Website | u-tokyo.ac.jp |

| |

The University of Tokyo (UTokyo, 東京大学, Tōkyō daigaku) is a public research university in Bunkyō, Tokyo, Japan. Founded in 1877 by the merger of several pre-westernisation era institutions such as the Shoheizaka Institute (founded in 1605) and Kaiseijo, it is the nation's oldest modern university.[6]

UTokyo consists of 10 faculties, 15 graduate schools, and 11 affiliated research institutes.[7] As of 2023, it has a total of 13,974 undergraduate students and 14,258 graduate students.[7]

The majority of the university's educational and research facilities are concentrated within its three main Tokyo campuses: Hongo, Komaba, and Kashiwa.[8] UTokyo also operates several smaller campuses throughout the Greater Tokyo Area. In addition, the university boasts over 60 facilities and offices spread across the Japanese archipelago and the world, each contributing uniquely to the university's activities. [9][10] UTokyo's total land holdings amount to 326 square kilometres (approximately 80,586 acres, 32,604 hetares, 0.1 per cent of Japan's total land area).[11]

UTokyo boasts a distinguished network of alumni, faculty members, and researchers. As of 2021, UTokyo's alumni, faculty members and researchers include 17 prime ministers of Japan (out of 64), 18 Nobel Prize laureates, four Pritzker Prize laureates, five astronauts, and a Fields Medalist.[12]

As of November 2023, UTokyo alumni held 139 seats in the National Diet (parliament), representing 19.5 per cent of the total 713 seats.[13][14] Eleven out of the fifteen incumbent justices of the Supreme Court were UTokyo alumni. Additionally, UTokyo alumni have founded some of Japan's largest companies, such as Toyota Motor[15] and Hitachi.[16] As of 2014, UTokyo alumni held chief executive positions at 47 of the Nikkei 225 companies, making it the top source of these high-level corporate leaders.[17] This number includes Sony, MUFG, SMBC, Mitsui Corp, Mitsubishi Corp, and Japan Post.[18][19][20]

History

Founding

The University of Tokyo was chartered in 1877 under its current name (東京大學 Tokyo daigaku), by the Meiji government. It was founded as an amalgamation of older government schools for medicine, astronomy, and various other traditional and modern learning disciplines. In 1886, the university was renamed Imperial University (帝國大學, Teikoku daigaku), and it adopted the name Tokyo Imperial University (東京帝國大學, Tōkyō teikoku daigaku) in 1897, when another imperial university, namely Kyoto Imperial University, was founded using the war reparations from the First Sino-Japanese War.[21]

By 1888, all faculties had completed their relocation to the former site of the Tokyo house of the Maeda family in Hongo, where they continue to operate today. Among the few remnants from before this relocation, the most significant is a gate called Akamon (赤門), which has become a widely recognised symbol of the university.

During its initial two decades as a modern institution, UTokyo greatly benefited from the contributions of European and American scholars, laying a solid foundation for high-quality education and research. In 1871, the Meiji Government made a decision about the direction of academic disciplines: engineering was to be learnt from the United Kingdom, mathematics, physics, and international law from France, while politics, economics, and medicine were to be guided by German expertise. Additionally, agriculture and commercial law knowledge was to be sourced from the United States.[22]

Following this policy, UTokyo and its predecessor institutions sent their graduates to universities in these respective countries and also invited lecturers from there. This led to each faculty at UTokyo adopting distinct research and educational methodologies, reflecting of the academic customs of their respective model countries. However, by the 1880s, the Japanese government grew concerned over the influence of French republican and British constitutional monarchist ideals among the faculty and students of this premier educational establishment. Consequently, the Minister of Education, Takato Oki, instructed UTokyo to reduce the use of English as a language of instruction, and instead to switch to Japanese.[23] This shift coincided with the return of UTokyo alumni who had completed their education in Europe, and these returnees began filling roles that were predominantly held by foreign scholars.

Pre-war period

Great Kanto Earthquake

On 1 September 1923, the Great Kanto Earthquake struck the Kanto Plain, inflicting immense damage upon the university. This damage included the complete destruction of almost all main buildings, including the library, as well as the loss of precious scientific and historical samples and data stored in them.[24][25] This led to a university-wide debate as to whether it should relocate to a larger site, such as Yoyogi, but ultimately, such plans were rejected. Instead, the university purchased additional land in its vicinity, which was still owned by the Maeda family, and expanded there.

The reconstruction of the university and its library was brought up in the fourth general assembly of the League of Nations in September 1923, where it was unanimously decided to provide support. The American philanthropist John D. Rockefeller Jr. personally donated $2 million (approximately $36 million in 2023). The United Kingdom formed a committee led by former Prime Minister Earl Arthur Balfour, and made significant contributions, both financially and culturally. [26] A large portion of the buildings on Hongo Campus today were built during this reconstruction period, and their unique Collegiate Gothic style is known as Uchida Gothic (内田ゴシック) after Yoshikazu Uchida, the architect who designed them.[27]

World War II

In 1941, the Empire of Japan attacked the American bases at Pearl Harbor and joined the World War II as an Axis power alongside Germany. By late 1943, as Japan faced significant defeats in the Pacific theatre, a decision was made to enlist university students studying humanities, sending them to battlefields. During the war, 1,652 students and alumni of UTokyo were killed, including those from varied civilian professions such as doctors, engineers, and diplomats, as well as those killed in action.[28] They are commemorated in a memorial erected near the front gate of the Hongo Campus. Most students from faculties of engineering and science remained at university or worked as apprentice engineers, as the expertise of science and technology was deemed indispensable for the war effort.

The increased demand brought about by the war for engineers, especially in the fields of aeronautics, machinery, electronics, and shipbuilding, led to the establishment of the second faculty of engineering (第二工学部) at UTokyo in 1942. In the newly-built Chiba Campus, around 800 students were enrolled at one time, and pivotal military engineering research activities were conducted. It was closed in 1951, and as a successor organisation, the Institute of Industrial Science was established on the site of the former headquarters of the Third Infantry Regiment in Roppongi.[29][30]

Leo Esaki, who was a student at the department of physics during the war, shared his memory of his university life in 2007: 'The day after the Tokyo Air Raid of 9 March 1945, during which more than 100 thousand citizens were killed, professor Tanaka conducted class as usual, without mentioning the war at all'.[31] The buidings and facilities of UTokyo were largely immune from air raids, allowing education and research activities to continue.

Post-war period

During the American occupation era following Japan's defeat in World War II, the university dropped the word 'imperial' (帝国) from its name and returned to its original name, the University of Tokyo (東京大学). During this period, Japan's education system was reformed to align more with the American system. As a result, UTokyo merged with two Higher Schools, which were university preparatory boy's boarding schools and thus became a four-year university as it is today in 1949. It was also during this period that UTokyo first opened its doors to female students.

UTokyo Conflict

The 1960s saw an intensification of student protests across the world, including the Anti-Vietnam War protests and the May 68 events in France. This zeitgeist of the era was prominently felt in Japan as well, symbolised by the 1960 Anpo protests, in which the death of a UTokyo student, Michiko Kamba, caused public outrage. In 1968, the Todai Funsou (東大紛争, UTokyo Conflict) began with medical students demanding improvements in internship conditions, in which medical students were forced to work long hours without being paid before being licensed as a doctor.

The conflict intensified with the indefinite strike decision by the students in January 1968 and escalated further following a clash between the students and faculty. Tensions peaked when radical students, most of whom were members of the Zenkyōtō (the All-Campus Joint Struggle Committees), occupied Yasuda Auditorium, leading the university to eventually call in riot police in June— a move seen as abandoning university autonomy. Efforts to resolve the situation began with the resignation of university executives and the appointment of Kato Ichiro as interim president, who started negotiations. The conflict largely ended in January 1969 after a full-scale police operation to remove the occupying students. This operation involved more than 8,500 riot police officers confronting students who fought back with Molotov cocktails and marble stones taken from the auditorium's interior.[32] Prime Minister Eisaku Sato, an alumnus of UTokyo himself (Law, 1924), visited the university the day after the protesters in the auditorium were forcibly removed, and, in tears, decided to cancel that year's entrance exam. This led top highschool students to apply reluctantly to other universities such as Kyoto University and Hitotsubashi University, resulting in many applicants who would have been admitted to those universities under normal circumstances failing to gain admission.[33] (In Japan, applicants are not allowed to apply to multiple prestigious national universities.) The aftermath saw 767 arrests, 616 prosecutions, and varied sentences, marking a turbulent chapter in the university's history.

21st century

Women's education

Although the university first admitted female students in 1946, the student body has remained predominantly male since then. While it is said that the university alone cannot fully address this issue, as it is deep rooted in Japanese society,[34] various attempts have been made to achieve a more equal gender ratio. In 2023, women made up 23 per cent of the freshers, the highest percentage in the university's history. [35] A quarter of graduate students were female in 2022, and the university is working to improve the percentage further both at the undergraduate and graduate levels.

International education

As one of Japan's premier educational institutions, it is widely agreed amongst UTokyo's faculty members and students that one of the university's primary roles is to provide comprehensive, high-quality tertiary education in the Japanese language. Shifting the primary language of teaching to English just for the sake of globalisation is believed to undermine the unique values only UTokyo can offer. However, since Japanese is predominantly spoken only in Japan, it is argued that the language barrier deters international students from applying. In fact, international students make up only one-sixth of the total student body. Thus, globalising its campuses is one of the key issues that UTokyo has been eager to address.

At the undergraduate level, there are mainly three routes for those who have not received their secondary education in Japanese to apply to UTokyo. First, individuals with high Japanese proficiency can apply through the special admissions process for students educated overseas (外国学校卒業学生特別選考).[36] Students admitted via this route study alongside their peers who received secondary education in Japanese. International students who apply via this route sometimes spend a year studying the language at preparatory schools before matriculation. Second, there is an undergraduate programme called PEAK (Programs in English at Komaba), which accept applications based on international qualifications such as A-levels, SAT, and the International Baccalaureate. All modules in this programme are taught in English.[37] However, learning Japanese is mandatory, and those confident in their Japanese ability can take modules taught in Japanese in other departments. Third, UTokyo offers various exchange programmes with universities worldwide.[38] There are University-wide Student Exchange Programmes (USTEP) with universities such as Tsinghua University, Princeton University, National University of Singapore and Yale University.[39] The College of Arts and Sciences has its own exchange programmes called KOMSTEP with universities such as University of Paris. [40] The Faculty of Engineering also has its own exchange programmes, whose partner institutions include Petroleum Institute, Abu Dhabi, University of Cambridge, and Massachusetts Institute of Technology.[41]

Yasuda Auditorium, Hongo Campus

Yasuda Auditorium, Hongo Campus Institute for Solid State Physics, Kashiwa Campus

Institute for Solid State Physics, Kashiwa Campus Faculty of Engineering Bldg.1, Hongo Campus

Faculty of Engineering Bldg.1, Hongo Campus General Library, Hongo Campus

General Library, Hongo Campus Sanshiro Pond, Hongo Campus

Sanshiro Pond, Hongo Campus.jpg.webp) Komaba Campus

Komaba Campus An aerial photo of Hongo Campus in 1936

An aerial photo of Hongo Campus in 1936 Albert Einstein's visit to UTokyo in 1922

Albert Einstein's visit to UTokyo in 1922

Reforms in the 21st century

When the British magazine Times Higher Education first published its world university rankings in partnership with QS in 2004, UTokyo was ranked 12th in the world. In the latest 2024 edition of the rankings, it is ranked 29th.[42] QS, now has its own rankings, placed UTokyo at 28th.[43] As these numbers suggest, there is a widely shared concern that the university is falling behind its counterparts in the world, and in the future it may struggle to provide a suitable environment for quality education and world-class research.[44]

UTokyo faces a challenging reality. Japan's long-lasting economic downturn since the 1990s has led to Japanese companies less willing to invest in research and development than before.[45] Additionally, the government's Management Expense Grant (運営費交付金) has been reduced by one per cent annually since 2004.[46] This policy, ostensibly aimed at decreasing the university’s reliance on the grant and fostering greater independence, has been blamed as one of the main reasons for the decline in the university’s competitiveness.[47]

.png.webp)

To address these challenges, UTokyo has implemented various reforms. In 2004, UTokyo Edge Capital Partners (UTEC) was established. This venture capital firm, affiliated with the university, supports entrepreneurship arising from UTokyo’s research and development, aiming to drive innovation across society.[48] In 2006, the first phase of development was completed at Kashiwa Campus. Situated in the suburb of Kashiwa, this research-focused campus spans 405,313 square metres (100 acres) and has been at the forefront of advanced scientific research since its inception.[49] In 2010, in an attempt to further internationalise and diversify its student body, the university increased its autumn enronlemnt opportunities for international students.[50] UTokyo plans to increase the proportion of female faculty members to above a quarter by newly creating positions for 300 female lecturers by 2027.[51]

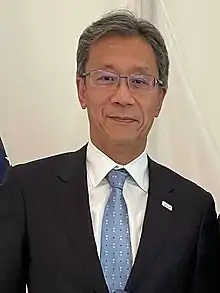

In 2021, the newly-elected President Teruo Fujii announced the UTokyo Compass, a guiding framework for the university during his tenure, focusing on diversity, dialogue, and creating a better future.[52] It emphasises the university's autonomy and creativity in a new era, advocating multifaceted perspectives on knowledge, people, and places. The Compass encourages dialogue throughout the university and society as a pivotal tool for understanding and questioning, fostering inclusivity, and tackling global challenges. In his announcement, he pledged to make UTokyo 'a university that anyone in the world would like to join'.[53]

Student life

Entrance examination

UTokyo's entrance exam (東大入試, todai nyushi) is regarded as the most selective in Japan and is almost synonymous with something that is difficult to achieve. To apply, candidates must achieve high scores in the Common Test for University Admissions (共通テスト) in January, a standardised multiple-choice examination. UTokyo applicants are required to take at least seven subjects in this exam. Applicants for natural sciences must take two mathematics tests, Japanese (which includes modern language, classics, and Chinese classics), English (reading and listening comprehension), Sciences (two from Physics, Chemistry, Biology, and Geology), and one Social Study subject (chosen from Geography, Japanese History, or World History). Humanities candidates must take two Social Studies subjects and one Science subject instead.[54]

Based on the scores from the Common Test, approximately three times the number of the final admission slots are invited to take the main exam in late February. Based on the idea that regardless of the field of specialisation, all students should have a solid understanding of mathematics and a good command of languages, mathematics, Japanese and one foreign language are compulsory for all applicants. For this exam, science candidates are tested in Advanced Mathematics, English, Japanese, and two science subjects. Humanities candidates take Mathematics, English, Advanced Japanese, and two social studies subjects (options are Geography, Japanese History, World History). UTokyo is also known to be the only university that requires all applicants, including those who wish to study natural sciences, to take a non-mulltiple-choice Japanese and Chinese classics exam. Some applicants are called upon to take an interview.[55]

Successful candidates are notified in March of the same year and are matriculated in April. The official acceptance rates for undergraduate degrees are relatively high, at around 30 per cent,[56] which is due to the policy of restricting the number of students who can sit for the exam based on the grades from the Common Test, to secure the quality of marking. Additionally, Japan's university admission policy does not allow applicants to apply to multiple prestigious national universities,[57] hence non-prospective students tend to switch to other national universities where they are more likely to secure admission.

The junior division

The matriculation ceremony takes place on 12 April, the foundation day of the university.[58] All freshers are matriculated at the College of Arts and Sciences at Komaba, which is a remnant of the time when the Komaba Campus served as the separate boarding school known as the First Higher School (第一高等学校) until 1949. [59] There, they spend the first one and a half years of their degrees. Students are required to study a foreign language they have never learnt for at least a year, with classes formed based on their choices. Popular languages include Chinese, French, German, Korean, Spanish, and Russian. These classes are meant to be places where students can interact with peers from different backgrounds and forge long-lasting friendships, especially since they spend a considerable amount of time together. There is a tradition where the previous year's class (uekura, 上クラ) invites the juniors to overnight orientation camps (ori gasshuku, オリ合宿) in early April.[60]

Freshers typically have 30-40 contact hours per week, although science students often have longer hours due to a larger number of compulsory modules such as linear algebra, advanced calculus, quantum physics, biology, and practicals.

Komaba is also the hub of most student societies and unions, with facilities including several tennis, football, and baseball courts, and arenas. For societies that don't involve physical activities, there are also four dedicated buildings that can accommodate about 100 societies, a theatre, and a Japanese-style building.

Intense academic competition is common among students in the junior division, as they face matriculation to the senior division (Shingaku Sentaku, 進学選択, or colloquially Shinfuri, 進振り) in September of their second year, where they are assigned to departments based on their grades for the first one and a half years at Komaba.[61] The Department of Information Science, the Faculty of Medicine, and the Department of Sociology are amongst the most selective departments in the Shingaku Sentaku.[62]

Student housing

Despite its roots as a boarding school, most undergraduates at UTokyo either live with their families at home or in non-university accommodation. Since the closure of the Komaba domitory (駒場寮, Komaba-ryo) in August 2001, there has been no on-campus accomodation for domestic students at UTokyo. There are four university domitories available for undergraduate students: Mitaka, Toshima, Oiwake and Mejirodai.[63] In 2021, approximately five per cent of the undergraduate students lived in one of the university domitories.[64] The university offers more options for international students, with on-campus dormitories available for them at Komaba and Kashiwa.

Student newspapers and magazines

The Todai Shimbun (東大新聞) is the oldest university newspaper still in operation, with its first issuance in 1920.[65] The editing committee of the newspaper has produced multiple central figures in the country's publishing industry. There are several other newer campus newspapers and magazines, the most notable of which is the Kokasha (恒河沙).[66] The Kokasha's start-of-term issues include evaluations of lecturers by students from the previous year, and are widely read by students in the junior division to decide which modules to take at the beginning of terms. Additionally, there are several other relatively new student magazines, such as the biscUiT,[67] the Todai Shimpo and the Komaba Times.[68] Apart from those, student web media such as the UT-base[69] and the UmeeT are widely read by students.

The senior division

After completing the Shingaku Sentaku, second-year students matriculate into senior division departments to specialise in their chosen fields. With the exception of the senior division of the College of Arts and Sciences and the Department of Mathematics, which are located in Komaba, all other senior departments are situated in Hongo. Consequently, approximately 85 per cent of the students start a new chapter of their university life there.[70]

The Hongo Campus is located closer to the centre of Tokyo, providing access to more restaurants, cafes, and large museums in the vicinity. In addition to these, the campus itself boasts four refectories, eight restaurants, six cafes, five convenience stores, seven kiosks, two bookstores, two barbershops, and an underground gym with two 25-metre pools, making it a comfortable place for students to spend time.[71][72]

While students typically become busier with their studies in the senior division, they are encouraged to take modules from other faculties to develop interdisciplinary perspectives in addition to their major studies.

Students in the sciences often begin participating in research activities towards the beginning of their final year under the guidance of their supervisor and submit their thesis in January. Students in the humanities generally follow a similar path but are part of seminars (zemi, ゼミ) rather than laboratories.

Graduation ceremonies take place towards the end of March. Approximately one-third of the graduates enter the workforce upon graduation, while the remainder continue their studies at graduate schools within UTokyo or at universities abroad.[73] Popular places of employment for UTokyo graduates include UTokyo itself, governmental ministries, global conglomerates such as Sony and Hitachi, consulting firms such as McKinsey & Company and PwC Consulting, trading companies (商社, shosha) such as Mitsubishi Corp and Mitsui Corp, and investment banks.[74]

Organisation

UTokyo operates under a central administration system, with policies often determined by the administrative council led by the president.[75] However, due to the university's history as an amalgamation of various institutions, each of the university's constituent colleges, faculties and institutes has its own administrative board. Today, UTokyo is organised into 10 faculties[76] and 15 graduate schools.[77]

The leader of UTokyo is known as the president (総長, socho) and it is not a ceremonial role. They are elected every six years by the university's board council from among the faculty members. The current president is Teruo Fujii, a scholar in applied microfluidics, who assumed the role in April 2021 and is expected to serve until March 2027.[78]

Faculties and graduate schools

At the centre of UTokyo's research and education efforts are 10 faculties and their affiliated graduate schools. This organisational structure, introduced as a result of reforms in the 1990s, aims to maximise the outcomes of education and research by integrating them across undergraduate and graduate levels, rather than maintaining separate focuses for each.[79]

| Faculty | Founded | Locations | Affiliated graduate schools | Colour | Website |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Law | 1871 | Hongo | Graduate Schools for Law and Politics | Green | https://www.j.u-tokyo.ac.jp/en/ |

| Medicine | 1868 | Hongo, Shirokane | Graduate School of Medicine | Red | https://www.m.u-tokyo.ac.jp/english/ |

| Engineering

(工学部) |

1871 | Hongo, Kashiwa, KomabaII, Asano | Graduate School of Engineering, Graduate School of Frontier Sciences, Graduate School of Information Science and Technology | White | https://www.t.u-tokyo.ac.jp/en/foe |

| Letters

(文学部) |

1868 | Hongo | Graduate School of Humanities and Sociology | None | https://www.l.u-tokyo.ac.jp/eng/index.html |

| Science | 1877 | Hongo, Komaba(maths) | Graduate School of Science, Graduate School of Mathematical Sciences | Benikaba | https://www.s.u-tokyo.ac.jp/en/ |

| Agriculture

(農学部) |

1886 | Hongo (Yayoi) | Graduate School of Agricultural and Life Sciences | Indigo | https://www.a.u-tokyo.ac.jp/english/ |

| Economics

(経済学部) |

1919 | Hongo | Graduate School of Economics | Blue | https://www.e.u-tokyo.ac.jp/index-e.html |

| Arts and Science

(教養学部) |

1886 | Komaba | Graduate School of Arts and Sciences | Black and Yellow | https://www.c.u-tokyo.ac.jp/eng_site/ |

| Education

(教育学部) |

1949 | Hongo, Nakano | Graduate School of Education | Orange | https://www.p.u-tokyo.ac.jp/english/ |

| Pharmaceutical Sciences

(薬学部) |

1958 | Hongo | Graduate School of Pharmaceutical Sciences | Enji | https://www.f.u-tokyo.ac.jp/en/ |

In addition to the graduate schools affiliated with specific faculties, UTokyo also includes two independent graduate institutions: the Graduate School of Interdisciplinary Information Studies and the Graduate School of Public Policy (GraSPP).

Research institutes

Apart from the faculties and graduate schools, UTokyo hosts eleven affiliated research institutes. (附置研究所) These institutes serve as research hubs in their respective fields, aiming to widely disseminate their findings for societal benefit. Simultaneously, they function as educational institutions for the graduate schools.[80][81][82]

| Institute | Website | |

|---|---|---|

| Atmosphere and Ocean Research Institute

(大気海洋研究所) |

Advances basic research on oceans and atmosphere, focusing on climate change and evolution of life, and offers graduate education. | link |

| Earthquake Research Institute

(地震研究所) |

Conducts basic research on earthquakes and volcanic phenomena, aiming at disaster prevention and mitigation. | link |

| Historiographical Institute

(史料編纂所) |

Focuses on collecting, researching, and editing historical documents, especially in the field of pre-modern Japanese history. | link |

| Institute for Advanced Studies on Asia (Formerly known as Institute of Oriental Culture)

(東洋文化研究所) |

Specialises in comprehensive studies of Asia, including humanities and social sciences, and collaborates internationally. | link |

| Institute for Cosmic Ray Research

(宇宙線研究所) |

Observes cosmic rays and particles for research in astrophysics and particle physics. | link |

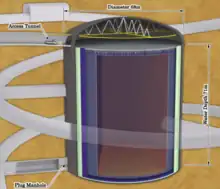

| Institute for Solid State Physics

(物性研究所) |

Researches the properties of materials at the microscopic level, using advanced technologies such as quantum beams and supercomputers. | link |

| Institute of Industrial Science

(生産技術研究所) |

Engages in applied research integrating various fields of engineering, covering almost all aspects of engineering. | link |

| Institute of Medical Science

(医科学研究所) |

Focuses on diseases such as cancer and infectious diseases, aiming at innovative treatment methods including genomics and AI in healthcare. | link |

| Institute for Quantitative Biosciences

(定量生命科学研究所) |

Conducts advanced research in describing all life dynamics by physical quantities, incorporating fields such as mathematics, physics, and chemistry. | link |

| Institute of Social Science

(社会科学研究所) |

Aims at producing 'comprehensive knowledge' in social sciences, conducting joint research and providing an international platform for empirical social science research. | link |

| Research Center for Advanced Science and Technology

(先端科学技術研究センター) |

Engages in interdisciplinary research in various fields such as materials, environment, information, and social sciences, aiming at pioneering new scientific and technological areas. | link |

UTokyo Institutes For Advanced Study (UTIAS)

UTokyo Institutes For Advanced Study (UTIAS) started in January 2011. Its primary objective is to improve academic excellence and foster an internationalised research environment. There are four UTIAS institutes as of November 2023:[83]

| Institute | Website | |

|---|---|---|

| Tokyo College | Established in February 2019 to collaboratively explore the future of humanity and Earth. Engages in interdisciplinary research on themes such as the digital revolution, Earth's limits, Japan's future, future humanities, and the future of life. It also acts as a host institution for visiting professors, including Jack Ma, the founder of Alibaba Group. [84][85] | link |

| Kavli Institute for the Physics and Mathematics of the Universe | Focuses on fundamental questions about the universe, including dark energy, dark matter, and unified theories, with interdisciplinary approaches involving mathematics, physics, and astronomy. | link |

| International Research Center for Neurointelligence (IRCN) | Established in October 2017 to create a new field of 'Neurointelligence'. Integrating life sciences, medicine, linguistics, mathematics, and information science, it chiefly aims to further understand human intelligence, and utilise the outcomes to overcome mental illnesses, and develop new types of AI based on brain functioning. | link |

| The University of TOkyo Pandemic preparedness, Infection and Advanced research center (UTOPIA) | Established in October 2022, its aim is to equip the society with resilience against future pandemics through fundamental research in infectious diseases, immunity. It takes multi-disciplinary approaches involving immunology, structural biology, AI, and social sciences, and aims to develop systems for quickly providing effective and safe vaccines and treatments in emergencies. | link |

UTokyo library system

The University of Tokyo Library System consists of three comprehensive libraries located on the main campuses—Hongo, Komaba, and Kashiwa—along with 27 other field-specific libraries operated by various faculties and research institutes.[86] As of 2023, the UTokyo library boasts a collection of over 9.9 million books and numerous materials of historical importance.[87] This extensive collection ranks it as the second-largest library in Japan, surpassed only by the National Diet Library, which holds a collection of approximately 46.8 million books.[88] It also subscribes to about 170,000 journals, contributing to research activities throughout the university.

The headquarters of the library is situated in the General Library at Hongo, which underwent thorough renovation in the late 2010s. It now features a 46-metre-deep automated storage capable of housing approximately 3 million books.[89]

Museums

Nikko Botanical Garden

Nikko Botanical Garden An Egyptian Horus sculpture

An Egyptian Horus sculpture UMUT

UMUT Exhibition in UMUT

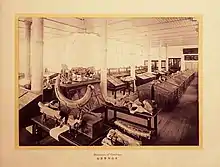

Exhibition in UMUT The University Museum, circa 1900

The University Museum, circa 1900

UTokyo operates eight museums, three of which fall under the purview of the University Museum (UMUT) (東京大学総合研究博物館, Tōkyō daigaku sōgō kenkyū hakubutsukan). These museums play a crucial role in sharing significant findings from the university's research activities and showcasing its valuable collections with the public. They are also responsible for the preservation and maintenance of these collections.

| Museum | Location | Operator | Website | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| University Museum | The largest university museum in Japan, it has amassed over three million academic materials since 1877. It has hosted numerous planned exhibitions in addition to its permanent exhibition. | Hongo | UMUT | Link |

| INTERMEDIATHEQUE | A joint venture with Japan Post, it's housed in the JP Tower in Marunouchi and focuses on interdisciplinary experimentation, showcasing scientific and cultural heritage. | JP Tower, Marunouchi, Chiyoda | UMUT/Japan Post | Link |

| University Museum, Koishikawa Annex | Located in one of the University of Tokyo's oldest buildings, it displays architectural models and photographs documenting the construction of various famous structures from around the world. | Koishikawa botanical garden | UMUT | Link |

| Komaba Museum | Combining an art and a natural science museum, it features collaborative exhibitions that transcend the boundaries of liberal arts and science. | Komaba | College of Arts and Sciences | Link |

| Museum of Health and Medicine | Provides information about health and medicine. | Hongo | Faculty of Medicine | Link |

| Medical Science Museum | Aims to preserve and display historical medical materials, offering a tranquil environment for visitors to reflect on the past, present, and future of medical science. | Shirokanedai | Institute of Medical Sciences | Link |

| Farm Museum | Located in a renovated dairy barn in the Tanashi University Farm, it showcases farming implements and other agricultural artefacts. | Tanashi farm | Faculty of Agriculture | |

| Agricultural Museum | Displays items related to agriculture, including artefacts such as Hachiko's internal organs. | Yayoi | Faculty of Agriculture |

Apart from the aforementioned museums, UTokyo operates several other public facilities, the most notable of which are two botanical gardens managed by the Faculty of Science: Koishikawa and Nikko. These gardens, renowned for their diverse botanical collections and historical significance, offer unique educational and recreational opportunities for visitors and researchers.

| Koishikawa Botanical Garden | Established in 1684, this botanical garden has been operated by UTokyo since its foundation as a modern university in 1877.[90] It was in this garden that in 1894 Hirase Sakugoro the discovered spermatozoids of the ginkgo, proving that gymnosperms produce sperm cells. The garden is designated as a National Monument (名勝, meishō) and is open to the public for an admission fee of 500 yen (free for UTokyo students and faculty). [91] |

| Nikko Botanical Garden | Opened in 1902 as an annex to the Koishikawa Garden, this facility is located in the highland resort town of Nikko and primarily focuses on alpine plants. It has become a popular tourist destination in Nikko and is accessible to the public with an admission fee of 500 yen.[92] |

Notable research

Since its foundation in 1877 as a modern university, UTokyo has conducted numerous research projects across various fields, achieving notable outcomes. Below are some widely-recognised research endeavours conducted by individuals affiliated with UTokyo at the time of their research.

- In 1904, Hantaro Nagaoka, an alumnus and professor in the Department of Physics, devised the Saturnian model of the atom. Contrasting with J. J. Thomson's then-popular plum pudding model, Nagaoka's model proposed an atomic structure with a heavy nucleus at the centre and electrons revolving around it.[93] Although this model assumed a far larger nucleus than in reality, it inspired Ernest Rutherford's Rutherford model.[94]

- Teiji Takagi, an alumnus and professor of the Department of Mathematics, proved the Takagi existence theorem in the 1910s. Alongside significant contributions to algebraic number theory, he also introduced the Blancmange curve, a well-known example of a self-affine curve.

- In 1951, Kiyoshi Ito, as a doctoral student in the Department of Mathematics, pioneered the theory of stochastic integration and stochastic differential equations, now known as Itô calculus. This theory is best known for its application in mathematical finance, namely in the Black–Scholes equation for option values.

Ito Integral (blue) of a Brownian motion (red)

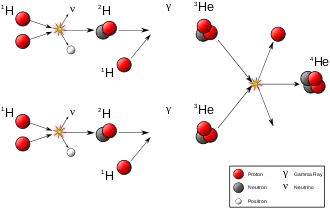

Ito Integral (blue) of a Brownian motion (red) - On 23 February 1987, the Kamioka Nucleon Decay Experiment observatory, part of the Department of Physics, detected cosmic neutrinos for the first time in human history. This discovery significantly contributed to proving that the sun's energy is generated from hydrogen atoms combining into helium(proton-proton reaction chain). Masatoshi Koshiba, leader of this research group, was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2002.[95] In 1998, an expanded version of this neutrino observatory detected neutrino oscillation, demonstrating that the 'lepton flavour' of neutrinos changes. This discovery, proving that neutrinos have mass, led to Takaaki Kajita receiving the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2015.[96]

Proton-proton reaction

Proton-proton reaction

Academic rankings and reputation

| THE World[97] | General | 29 |

|---|---|---|

| QS World[98] | General | 28 |

| ARWU World[99] | Research | 27 |

UTokyo is considered to be the most selective and prestigious university in Japan and is counted as one of the best universities in the world.[6][100][101]

- Times Higher Education World University Rankings ranked UTokyo 29th in the world in 2023.[102]

- QS World University Rankings[103] ranked UTokyo 28th in the world in 2023.

- The Times Higher Education World Reputation Rankings 2022 ranked UTokyo 10th in the world (2nd in Asia).

- Nature Index ranked UTokyo 6th in 2015 and 8th in 2017 in its Annual Tables, which measure the largest contributors to papers published in world's 82 leading journals.[104][105][106]

- In the Nature Index Annual Tables 2021, UTokyo was ranked 8th based on 1,308 Natural science research treatises published by the university. In the field of physical science treatises, it ranked second in the world among universities.[107]

- In 2019, The University of Tokyo ranked 24th among the universities around the world by SCImago Institutions Rankings.[108]

- In 2017, Times Higer Education's Alma Mater Index ranked UTokyo 16th in the world. This index ranked universities according to how many qualifications they have awarded to chief executives of companies that appear in Fortune magazine’s Fortune Global 500.[109]

- In 2023, Newsweek recognised the UTokyo Hospital as the 17th best hospital in the world (2nd in Asia after Singapore General Hospital, 1st in Japan). [110]

Sites

Hongo campus

The main Hongo campus occupies the former estate of the Maeda family, Edo period feudal lords of Kaga Province.[111] One of the university's best known landmarks, Akamon (the Red Gate), is a relic of this era. The symbol of the university is the ginkgo leaf, from the trees found throughout the area. The Hongo campus also hosts UTokyo's annual May Festival.[112]

Akamon (the Red Gate)

Akamon (the Red Gate) Faculty of Medicine Bldg.2

Faculty of Medicine Bldg.2

The inside of the General Library

The inside of the General Library The Experimental Tank

The Experimental Tank Building one, Shared by the Faculties of Law and Letters

Building one, Shared by the Faculties of Law and Letters

Komaba Campus

The Komaba Campus, serving as the educational hub for the first two years of undergraduate studies, provides general education to around 6,000 first and second year students. The campus, also home to the Graduate Schools of Arts, Sciences, and Mathematical Sciences, boasts advanced research facilities. As a recognised "center of excellence," it supports about 450 senior division students in the College of Arts and Sciences and 1,400 graduate students across various disciplines.

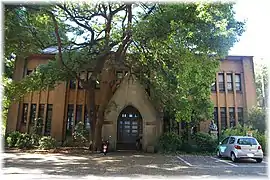

Komaba Campus Building 1

Komaba Campus Building 1 Auditorium 900

Auditorium 900 Main Refectory

Main Refectory_color.jpg.webp) The Institute of Industrial Science

The Institute of Industrial Science Research Centre for Advanced Science and Technology

Research Centre for Advanced Science and Technology

Kashiwa Campus

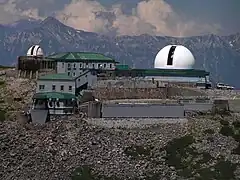

The Kashiwa Campus specialises in postgraduate education and research. It houses the Graduate School of Frontier Sciences along with advanced research institutes such as the Institute for Cosmic Ray Research, the Institute for Solid State Physics, the Kavli Institute for the Physics and Mathematics of the Universe, and the Atmosphere and Ocean Research Institute, equipped with extensive facilities and services.

The Kashiwa Campus boasts 100 acres of land

The Kashiwa Campus boasts 100 acres of land The institute for Cosmic Ray Research (ICRR), Kasiwa

The institute for Cosmic Ray Research (ICRR), Kasiwa A test track for the new generation of railway technology runs across the campus

A test track for the new generation of railway technology runs across the campus A former Tokyo Metro series 01 coach is used as a railway technology testbed

A former Tokyo Metro series 01 coach is used as a railway technology testbed The Kashiwa II Campus (20 acres) houses accomodation and athletic facilities for the students and faculty of the Kashiwa Campus

The Kashiwa II Campus (20 acres) houses accomodation and athletic facilities for the students and faculty of the Kashiwa Campus

Shirokanedai Campus

The relatively small Shirokanedai Campus[113] hosts the Institute of Medical Science of the University of Tokyo (IMSUT), which is entirely dedicated to postgraduate studies. The campus is focused on genome research, including among its facilities the Human Genome Center (HGC), which have at its disposal the largest supercomputer in the field.[114]

Other sites

.JPG.webp) Koishikawa Botanical Garden, Tokyo

Koishikawa Botanical Garden, Tokyo Norikura Solar Observatory

Norikura Solar Observatory Kemigawa Athletic Ground, Chiba

Kemigawa Athletic Ground, Chiba Chichibu Forest, Faculty of Agriculture, Saitama

Chichibu Forest, Faculty of Agriculture, Saitama KAGRA gravitational wave telescope, Gifu

KAGRA gravitational wave telescope, Gifu Atacama Observatory, Mount Chajnator, Chile

Atacama Observatory, Mount Chajnator, Chile Kemigawa Seminar House, Chiba

Kemigawa Seminar House, Chiba Atmosphere and Ocean Research Institute, Iwate, after the Tsunami of 11 March 2011

Atmosphere and Ocean Research Institute, Iwate, after the Tsunami of 11 March 2011 Nikko Botanical Garden, Tochigi

Nikko Botanical Garden, Tochigi

Notable people

Nobel laureates

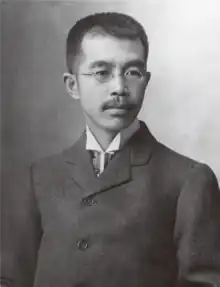

Yasunari Kawabata, Literature, 1968

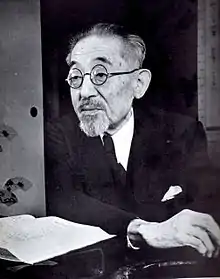

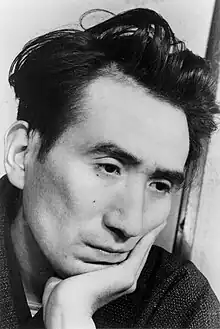

Yasunari Kawabata, Literature, 1968 Leo Esaki, Physics, 1973

Leo Esaki, Physics, 1973 Eisaku Satō, Peace, 1974

Eisaku Satō, Peace, 1974 Kenzaburō Ōe, Literature, 1994

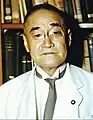

Kenzaburō Ōe, Literature, 1994 Masatoshi Koshiba, Physics, 2002

Masatoshi Koshiba, Physics, 2002 Yoichiro Nambu, Physics, 2008

Yoichiro Nambu, Physics, 2008 Ei-ichi Negishi, Chemistry, 2010

Ei-ichi Negishi, Chemistry, 2010 Takaaki Kajita, Physics, 2015

Takaaki Kajita, Physics, 2015.jpg.webp) Yoshinori Ohsumi, Physiology or Medicine, 2016

Yoshinori Ohsumi, Physiology or Medicine, 2016.jpg.webp) Syukuro Manabe, Physics, 2021

Syukuro Manabe, Physics, 2021

Other notable people

Kiichiro Toyoda, founder of Toyota Motors

Kiichiro Toyoda, founder of Toyota Motors

Kazuo Ueda, Governor of Bank of Japan

Kazuo Ueda, Governor of Bank of Japan.jpg.webp)

Yuji Iwasawa, judge of International Court of Justice and Yoko Kamikawa, Minister for foreign affairs

Yuji Iwasawa, judge of International Court of Justice and Yoko Kamikawa, Minister for foreign affairs

Namihei Odaira, the founder of Hitachi

Namihei Odaira, the founder of Hitachi

Kenichiro Yoshida, CEO of Sony

Kenichiro Yoshida, CEO of Sony Iemasa Tokugawa, duke, diplomat

Iemasa Tokugawa, duke, diplomat

See also

- Earthquake engineering

- Imperial College of Engineering

- International Journal of Asian Studies – published in association with the Institute for Advanced Studies on Asia, University of Tokyo

- Kikuchi Dairoku

- Koishikawa Botanical Gardens

- Nikko Botanical Garden

- The University of Tokyo Library

- The University Museum, The University of Tokyo

References

- ↑ "令和3年度 予算" (PDF). 東京大学. March 11, 2021. Retrieved December 9, 2023.(in Japanese)

- ↑ "教職員数(令和4年5月1日現在) - 常勤教員(教授~助手の計)". 東京大学. May 1, 2022. Archived from the original on October 6, 2021. Retrieved October 6, 2021.(in Japanese)

- ↑ Details on the number of students "学生数の詳細について - 在籍者". u-tokyo.ac.jp. Archived from the original on June 5, 2021. Retrieved August 19, 2022.(in Japanese)

- ↑ The number of regular students, research students and auditors 令和4年5月1日現在 学部学生・研究生・聴講生数調 - 在籍者 Archived 2022-09-03 at the Wayback Machine(in Japanese)

- ↑ The number of graduate students, research students and international research students 令和4年5月1日現在 大学院学生・研究生・外国人研究生数調 - 在籍者 Archived 2022-07-21 at the Wayback Machine(in Japanese)

- 1 2 Japanese journalist Kiyoshi Shimano ranks its entrance difficulty as SA (most selective/out of 10 scales) in Japan. 危ない大学・消える大学 2012年版 (in Japanese). YELL books. 2011. ISBN 978-4-7539-3018-0.

- 1 2 "The University of Tokyo". The University of Tokyo. Retrieved November 3, 2023.

- ↑ "The University of Tokyo". The University of Tokyo. Retrieved November 6, 2023.

- ↑ "海外拠点リスト". 東京大学 (in Japanese). Retrieved November 3, 2023.

- ↑ "全国施設分布図". 東京大学 (in Japanese). Retrieved November 3, 2023.

- ↑ "施設等所在地". 東京大学 (in Japanese). Retrieved November 10, 2023.

- ↑ "The University of Tokyo". The University of Tokyo. Archived from the original on October 26, 2011. Retrieved July 12, 2019.

- ↑ "議員情報". www.shugiin.go.jp. Retrieved November 10, 2023.

- ↑ "議員一覧(50音順):参議院". www.sangiin.go.jp. Retrieved November 10, 2023.

- ↑ "» Kiichiro Toyoda | Automotive Hall of Fame". www.automotivehalloffame.org. Retrieved November 10, 2023.

- ↑ Ltd, Hitachi. "Legacy of Meister Namihei Odaira : Hitachi Review". www.hitachi.com. Retrieved November 10, 2023.

- ↑ サンデー毎日 2014年 3/23号 (in Japanese). 毎日新聞社.

- ↑ SHIMBUN,LTD, NIKKAN KOGYO. "【電子版】ソニー、次期社長に吉田憲一郎氏". 日刊工業新聞電子版. Retrieved November 10, 2023.

- ↑ 毎日放送, MBS. "数学好きの中学生は、やがて「三菱UFJフィナンシャル・グループ」社長に いま『パーパス経営』で変革に取り組む! | 3分で読める!『ザ・リーダー』たちの泣き笑い". MBSコラム (in Japanese). Retrieved November 10, 2023.

- ↑ "「安永 竜夫」の記事一覧". PRESIDENT Online(プレジデントオンライン) (in Japanese). Retrieved November 10, 2023.

- ↑ "The University of Tokyo". The University of Tokyo, About UTokyo, Chronology. Retrieved November 6, 2023.

- ↑ "四 海外留学生と雇外国人教師:文部科学省". www.mext.go.jp. Retrieved December 1, 2023.

- ↑ Terasaki, Masao (1992). プロムナード東京大学史, Short History of the University of Tokyo (in Japanese). Tōkyō: Tōkyō Daigaku Shuppankai. p. 161. ISBN 4-13-003302-6.

- ↑ Earthquake disaster and reconstruction, The University of Tokyo 100-year history 東京大学百年史編集委員会, ed. (March 1985). 東大百年史 通史 (pdf). Vol. II. 東京大学. p. 385. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 6, 2021. Retrieved May 29, 2021. (in Japanese)

- ↑ LOST MEMORY – LIBRARIES AND ARCHIVES DESTROYED IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY ( Archived September 5, 2012, at the Wayback Machine)

- ↑ "記念特別展示会-世界から贈られた図書を受け継いで-". www.lib.u-tokyo.ac.jp. Retrieved November 3, 2023.

- ↑ "内田祥三・丹下健三と建築学の戦中・戦後" (in Japanese). Retrieved November 3, 2023.

- ↑ 谷本, 宗生 (March 31, 2014). "「学生とともに考える学徒出陣 70 周年―記憶と継承」―(東京大学附属図書館・東京大学史史料室共催)を終えて、一緒に考えてみたこと―" (PDF). 東京大学資料室ニュース (52).

- ↑ Hirasawa, Hideo (2012). "第二工学部の思い出". 生産研究. 64 (3): 399 – via JSTAGE.

- ↑ "沿革・歴代研究科長". 東京大学工学部 (in Japanese). Retrieved December 9, 2023.

- ↑ "東京大学創立130周年記念事業". www.u-tokyo.ac.jp. Retrieved December 1, 2023.

- ↑ "9章 東大紛争-ビジュアル年表(戦後70年):朝日新聞デジタル". www.asahi.com. Retrieved December 9, 2023.

- ↑ "東大入試中止、そのとき受験生は――コロナ禍を超える1969年大学入試の混乱". AERA dot. (アエラドット) (in Japanese). August 27, 2020. Retrieved December 9, 2023.

- ↑ "Sex imbalance at Japan's top university is nothing to worry about". Nikkei Asia. Retrieved November 3, 2023.

- ↑ 日本放送協会 (April 12, 2023). "東京大学で入学式 女子学生の割合 過去最高の23% | NHK". NHKニュース. Retrieved November 3, 2023.

- ↑ "外国学校卒業学生特別選考第1種:私費留学生・第2種:帰国生徒". 東京大学 (in Japanese). Retrieved November 3, 2023.

- ↑ "The University of Tokyo, PEAK - Programs in English at Komaba | HOME". peak.c.u-tokyo.ac.jp. Retrieved November 3, 2023.

- ↑ "The University of Tokyo". The University of Tokyo. Retrieved November 3, 2023.

- ↑ "The University of Tokyo". The University of Tokyo. Retrieved November 4, 2023.

- ↑ "Partner Universities | The University of Tokyo". www.globalkomaba.c.u-tokyo.ac.jp. Retrieved November 4, 2023.

- ↑ "OICE: Partner Universities 「協定校一覧」". www.oice.t.u-tokyo.ac.jp. Retrieved November 4, 2023.

- ↑ "World University Rankings". Times Higher Education (THE). September 25, 2023. Retrieved November 3, 2023.

- ↑ "QS World University Rankings 2024". Top Universities. Retrieved November 3, 2023.

- ↑ "駒場をあとに「惜別の辞に代えて」 - 教養学部報 - 教養学部報". www.c.u-tokyo.ac.jp. Retrieved November 10, 2023.

- ↑ "科学技術指標2021・html版 | 科学技術・学術政策研究所 (NISTEP)". Retrieved November 10, 2023.

- ↑ Takeuchi, Kenta (2019). "国立大学法人運営費交付金の行方 ― 「評価に基づく配分」をめぐって ―" (PDF).

- ↑ "17年度国立大授業料" (PDF). 旺文社 教育情報センター. Retrieved November 10, 2023.

- ↑ Ltd, UTEC-The University of Tokyo Edge Capital Partners Co. "UTEC-The University of Tokyo Edge Capital Partners Co., Ltd". UTEC-The University of Tokyo Edge Capital Partners Co., Ltd. Retrieved November 3, 2023.

- ↑ "柏キャンパス – 柏キャンパス" (in Japanese). Retrieved November 3, 2023.

- ↑ 東京大学広報室 (October 25, 2010). "「特集:■平成22年度秋季学位記授与式・卒業式■平成22年度秋季入学式」(PDF)" (PDF). 『学内広報』第1404号. Retrieved November 3, 2023.

- ↑ 日本放送協会 (November 27, 2022). "東京大学 女性の教授と准教授 約300人採用へ". NHKニュース. Retrieved November 3, 2023.

- ↑ "The University of Tokyo". The University of Tokyo. Retrieved December 9, 2023.

- ↑ "The University of Tokyo". The University of Tokyo. Retrieved December 9, 2023.

- ↑ "入学者選抜方法等の概要(学部)". 東京大学 (in Japanese). Retrieved November 3, 2023.

- ↑ "一般選抜". 東京大学 (in Japanese). Retrieved November 3, 2023.

- ↑ "入学者数・志願者数". 東京大学 (in Japanese). Retrieved December 29, 2023.

- ↑ "国立大学の入試 | 国立大学協会". www.janu.jp (in Japanese). Retrieved December 29, 2023.

- ↑ "東大の入学式は、なぜ12日開催なのか - 東大新聞オンライン". www.todaishimbun.org (in Japanese). April 10, 2016. Retrieved December 29, 2023.

- ↑ "The University of Tokyo". The University of Tokyo. Retrieved November 10, 2023.

- ↑ "クラス分け | キミの東大 高校生・受験生が東京大学をもっと知るためのサイト". キミの東大 (in Japanese). October 12, 2021. Retrieved November 10, 2023.

- ↑ "進学選択 | キミの東大 高校生・受験生が東京大学をもっと知るためのサイト". キミの東大 (in Japanese). November 9, 2018. Retrieved November 10, 2023.

- ↑ "[入門駒場ライフ] 科類・進学選択について|受験生・新入生応援サイト2023|東京大学消費生活協同組合". text.univ.coop. Retrieved November 3, 2023.

- ↑ "Housing Office | Housing Information | Accommodations Offered by UTokyo". www.u-tokyo.ac.jp. Retrieved December 29, 2023.

- ↑ "大学案内・選抜要項・募集要項". 東京大学 (in Japanese). Retrieved December 29, 2023.

- ↑ "団体紹介 - 東大新聞オンライン". www.todaishimbun.org (in Japanese). November 19, 2020. Retrieved December 29, 2023.

- ↑ "沿革 – 時代錯誤社" (in Japanese). Retrieved December 29, 2023.

- ↑ "ABOUT - biscUiT" (in Japanese). October 1, 2017. Retrieved December 29, 2023.

- ↑ "HOME". The Komaba Times. Retrieved December 29, 2023.

- ↑ "En page". UT-BASE. Retrieved December 29, 2023.

- ↑ "The University of Tokyo". The University of Tokyo. Retrieved November 10, 2023.

- ↑ "利用できる学内施設". 東京大学 (in Japanese). Retrieved November 3, 2023.

- ↑ "東京大学消費生活協同組合" (in Japanese). Retrieved November 10, 2023.

- ↑ "学部卒業者の卒業後の状況". 東京大学 (in Japanese). Retrieved November 3, 2023.

- ↑ "東京大学「就職先企業・団体」ランキング2022【全20位・完全版】". ダイヤモンド・オンライン (in Japanese). February 3, 2023. Retrieved December 29, 2023.

- ↑ "組織構成". 東京大学 (in Japanese). Retrieved November 3, 2023.

- ↑ "The University of Tokyo". The University of Tokyo. Archived from the original on November 16, 2018. Retrieved November 15, 2018.

- ↑ "The University of Tokyo". The University of Tokyo. Archived from the original on November 16, 2018. Retrieved November 15, 2018.

- ↑ "Prof. Teruo Fujii |". www.u-tokyo.ac.jp. Retrieved December 16, 2023.

- ↑ "特集 大学院を重点とする大学" (PDF). 東京大学広報誌 淡青 (2): 9. 2000.

- ↑ "The University of Tokyo". The University of Tokyo. Retrieved November 10, 2023.

- ↑ "附置研究所". 東京大学 (in Japanese). Retrieved November 10, 2023.

- ↑ "大学案内・選抜要項・募集要項". 東京大学 (in Japanese). Retrieved November 10, 2023.

- ↑ "The University of Tokyo". The University of Tokyo. Retrieved November 10, 2023.

- ↑ "MA Yun (Jack MA) - Tokyo College". www.tc.u-tokyo.ac.jp. Retrieved November 10, 2023.

- ↑ Pollard, Jim (May 1, 2023). "Jack Ma to be a Visiting Professor at Tokyo University". Asia Financial. Retrieved November 10, 2023.

- ↑ "The University of Tokyo". The University of Tokyo. Retrieved November 17, 2023.

- ↑ "統計表". 東京大学附属図書館 (in Japanese). Retrieved November 17, 2023.

- ↑ "統計|国立国会図書館―National Diet Library". www.ndl.go.jp. Retrieved November 17, 2023.

- ↑ "地下46mに300万冊納める東大の新図書館". 日本経済新聞 (in Japanese). November 7, 2017. Retrieved November 17, 2023.

- ↑ "小石川植物園について | 小石川植物園" (in Japanese). Retrieved November 17, 2023.

- ↑ "利用案内 | 小石川植物園" (in Japanese). Retrieved November 17, 2023.

- ↑ "Nikko Botanical Garden". www.bg.s.u-tokyo.ac.jp. Retrieved November 17, 2023.

- ↑ Bryson, Bill (2003). A Short History of Nearly Everything. Broadway Books. ISBN 0-7679-0817-1.

- ↑ Rutherford, Ernest (May 1911). "The Scattering of α and β Particles by Matter and the Structure of the Atom" (PDF). Philosophical Magazine. 21 (6).

- ↑ "The Nobel Prize in Physics 2002". NobelPrize.org. Retrieved November 10, 2023.

- ↑ "The Nobel Prize in Physics 2015". NobelPrize.org. Retrieved November 10, 2023.

- ↑ "THE World University Rankings". Times Higher Education. 2018. Retrieved September 24, 2017.

- ↑ "QS World University Rankings". QS Quacquarelli Symonds Limited. 2018. Retrieved September 24, 2017.

- ↑ "Academic Ranking of World Universities". Institute of Higher Education, Shanghai Jiao Tong University. 2017. Retrieved September 24, 2017.

- ↑ "Japan University Rankings 2017". Times Higher Education (THE). March 23, 2017. Archived from the original on June 5, 2021. Retrieved May 29, 2017.

- ↑ "World University Rankings". Times Higher Education (THE). August 17, 2016. Archived from the original on January 27, 2018. Retrieved May 29, 2017.

- ↑ "World University Rankings 2024". The Times Higher Education Supplement. 2023. Retrieved October 25, 2023.

- ↑ "QS World University Rankings". Topuniversities.com. Retrieved October 25, 2023.

- ↑ "Ten institutions that dominated science in 2015". April 20, 2016. Archived from the original on April 24, 2016. Retrieved May 28, 2019.

- ↑ "10 institutions that dominated science in 2017". June 12, 2018. Archived from the original on May 27, 2019. Retrieved May 28, 2019.

- ↑ "Introduction to the Nature Index". Archived from the original on April 1, 2019. Retrieved May 28, 2019.

- ↑ "2021 tables: Institutions | 2021 tables | Institutions | Nature Index". www.natureindex.com. Archived from the original on September 17, 2021. Retrieved June 6, 2021.

- ↑ "SCImago Institutions Rankings – Higher Education – All Regions and Countries – 2019 – Overall Rank". www.scimagoir.com. Archived from the original on April 22, 2019. Retrieved June 11, 2019.

- ↑ Durrans, Alice (January 18, 2017). "Where do the world's top CEOs go to university?". Archived from the original on November 27, 2019.

- ↑ Newsweek (March 1, 2023). "World's Best Hospitals 2023 - Top 250". Newsweek. Retrieved December 1, 2023.

- ↑ "Japan's new university entrance exams underway amid virus pandemic". The Japan Times. January 16, 2021. Archived from the original on January 16, 2021. Retrieved March 24, 2021.

- ↑ 第86期五月祭常任委員会. "トップページ|東京大学 第86回五月祭". 第86回五月祭公式ウェブページ. Archived from the original on 5 September 2015. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ "Shirokanedai Campus, The Institute of Medical Science, The University of Tokyo". Ims.u-tokyo.ac.jp. Archived from the original on September 28, 2018. Retrieved November 15, 2018.

- ↑ Human Genome Center, the Institute of Medical Science, the University of Tokyo. "Human Genome Center". Hgc.jp. Archived from the original on May 26, 2015. Retrieved June 12, 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

Further reading

- Kato, Mariko, "Todai still beckons nation's best, brightest but goals diversifying", Japan Times, August 11, 2009, p. 3.

- Kersten, Rikki. "The intellectual culture of postwar Japan and the 1968–1969 University of Tokyo Struggles: Repositioning the self in postwar thought." Social Science Japan Journal 12.2 (2009): 227–245.

- Marshall, Byron K. Academic Freedom and the Japanese Imperial University, 1868–1939 (University of California Press, 1992).

- Takashi, Tachibana, and Richard H. Minear. Tokyo University and the War (2017), on world war II; online.

External links

![]() Media related to University of Tokyo at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to University of Tokyo at Wikimedia Commons