| Indian Department | |

|---|---|

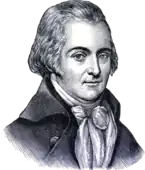

Sir William Johnson at the Battle of Lake George (1755) | |

| Active | 1755–1860 |

| Country | |

| Role | Diplomacy Guerrilla warfare Reconnaissance |

| Engagements | Seven Years' War (1755-1760) Pontiac's War (1763-1765) Revolutionary War (1775-1782) Northwest Indian War (1785-1795) War of 1812 (1811-1815) Canadian Rebellion (1837-1838) |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | Sir William Johnson Captain Joseph Brant Sir John Johnson Major John Norton |

The Indian Department was established in 1755 to oversee relations between the British Empire and the First Nations of North America. The imperial government ceded control of the Indian Department to the Province of Canada in 1860, thus setting the stage for the development of the present-day Department of Crown–Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada.

During its existence, the Indian Department served both a diplomatic and a military role. Its daily responsibilities were largely civil in nature, such as the administration of justice, the management of the fur trade, and the employment of blacksmiths, teachers, and missionaries. At the same time, the Department was expected to mobilize and lead Indigenous warriors in times of crisis and conflict.[1]

Theoretically, control over the Indian Department rested with the senior-most administrator in British America, initially the Commander-in-Chief of the British forces in North America, and later the Governor General of the Canadas. In practice, Indian Affairs were managed by the senior officers of the Indian Department themselves, upon whose advice the Governors General depended.

Mission

During the period 1755–1830, the mission of the Indian Department can be summarized as protecting the indigenous peoples from exploitation by traders and land speculators (one of the goals of the Royal Proclamation of 1763; negotiations with the First Nations about boundaries between their land and that of the agricultural colonists (such as the Treaty of Fort Stanwix 1768); distribute the gifts that the government gave to the indigenous people in order to create goodwill. First Nations who lived on American territory in the Midwest received gifts until 1830; in war, induce First Nations to support Britain with auxiliary troops (during the War of 1812, the Department acted in close cooperation with Chief Tecumseh).[2]

During the period 1830–1860, the Department’s major mission was to administrate the Indian Reserves.[3]

Organization

Subordination

During the period 1755–1796 the Commander-in-Chief, North America issued instructions for the Indian Department and maintained close connections with it. Yet, the Department was not directly subordinated to him, but to the Home Office in London.[2] In 1796, the Indian Department of Upper Canada became subordinated to the Lieutenant Governor of that province, while in 1800, the Governor General became responsible for the Department in Lower Canada. In 1816, the Indian Department in both Canadas was subordinated to the British commander-in-chief. The Department was again in 1830 divided into two departments; one in Upper Canada under the Lieutenant Governor, one in Lower Canada under the Military Secretary to the Governor General. The two departments were again merged and coming under the Governor General in 1840.[3]

Internal organization

In 1755, there were two departments, the Northern Department and the Southern Department; each having its own superintendent. The boundary between them ran along the Ohio River and the Potomac. During the American Revolutionary War, the Southern Department was divided into two; one in the west and one in the east. In 1782 the departments received a common superintendent.[2] After the Treaty of Paris of 1783, the area of responsibility became limited to Canada and the departments were formally merged into one organization. The office of superintendent was abolished in 1844 and the direct leadership was taken over ex officio by the Civil Secretary to the Governor-General.[3]

History

The early Indian Department, 1755-1774

Before 1755, responsibility for maintaining diplomatic relations with the Indigenous nations of North America rested with the individual British colonies. It was only the outbreak of the Seven Years' War that impelled the British Empire to centralize the management of Indian Affairs. Accordingly, Sir William Johnson was granted a special commission as Superintendent of Indian Affairs in 1755 in order to mobilize allied Indigenous warriors in the struggle against New France, and to win over or neutralize the Indigenous allies of the French.[4]

Initially, the administration of Indian Affairs in British America was divided into two geographical departments. The superintendent of the northern department, responsible for negotiations with the Indians living north of the Ohio River, was Sir William Johnson who held the position until his death in 1774. Sir William was succeeded by his son-in-law, Guy Johnson, who served as superintendent of Indian Affairs for the northern department until 1782.[5]

The first superintendent for the Southern Department was Edmond Atkins, starting in 1756. John Stuart became the Superintendent for the Southern Department in 1762, serving until his death in 1779.[6]

American Revolution, 1775-1782

During the American Revolutionary War, the Indian Department proved to be one of the most effective military forces at the disposal of the British Empire. Many Indigenous communities were bitterly opposed to the American settlers who had risen in rebellion, and therefore they made natural allies to the Loyalist cause. Joseph Brant rose to prominence as a leader of the Mohawk during the American Revolutionary War, during which he was appointed as a captain in the Indian Department.[7] His sister Molly Brant also played a critical role in the Indian Department during this time, and was afterwards granted a pension from the British government for her services during the Revolution.[8]

Northern Frontier

Fighting was particularly brutal in northern New York, where the homeland of the Six Nations was located. Sir John Johnson and John Butler were among the most active members of the Indian Department on this front. After the major British defeat at the Battles of Saratoga in 1777, warfare in this region consisted mostly of violent raids and counter raids. In 1778, The British Indian Department and its allies secured important victories at the Battle of Wyoming and the Raid on Cherry Valley. In the autumn of 1779, the American Sullivan Expedition was largely successful in destroying the corn fields and villages of the Six Nations. In revenge, Sir John Johnson and his Indigenous allies carried out a substantial raid against the settlements of upstate New York in 1780, known as the Burning of the Valleys.[9]

Ohio Country

The Indian Department also saw extensive fighting in the Ohio Valley region, where Alexander McKee, Matthew Elliott, and Simon Girty were among the most effective Loyalist partisans of the war.[10] Major engagements involving the Indian Department on this front included Captain Bird's Invasion of Kentucky, Crawford's Defeat, and the Battle of Blue Licks. The British Indian Department was particularly successful mobilizing warriors against the Americans in the Ohio Country following the massacre at Gnadenhutten of 96 pacifist Christian Munsee by Pennsylvania militiamen on March 8, 1782.[11]

After the Revolution, 1782-1812

_by_William_Berczy_-_1802-1812.jpg.webp)

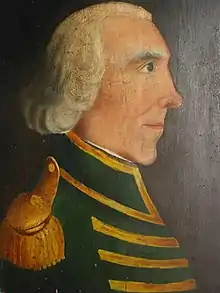

After the end of the Revolutionary War, Guy Johnson was removed from his position as Superintendent General of the Indian Department on suspicion of corruption. He was replaced by his brother-in-law Sir John Johnson, who held the position for nearly half a century until his death in 1830.[12]

Northwest War and Jay Treaty

During much of the period after the Revolution, the Indian Department was deeply concerned with the ongoing struggle between the Indigenous communities of the Ohio Valley and the young American republic. In the 1790s, this conflict flared into the Northwest Indian War. Despite tacit support from the Indian Department, the British Empire never openly sided with the Indigenous warriors. At the Battle of Fallen Timbers in 1794 the Northwestern Confederacy was defeated, leading the Treaty of Greenville in 1795.[13]

American victory in the Northwest War was followed by the Jay Treaty between the United States and the British Empire in 1796. While this treaty stipulated that the British, including the Indian Department, had to withdraw from the posts on American territory that the Empire had continued to occupy in defiance of the Treaty of Paris of 1783, it also contained a clause allowing Indigenous peoples to freely cross back and forth across the newly established international border. This clause allowed the Indian Department to continue to maintain close connections with Indigenous communities living in U.S. territory, such as the Shawnee, the Odawa, the Potawatomi, and the Dakota.[14]

Removal to Canada

Following the outbreak of the Revolutionary War, and again after the signing of Jay's Treaty, many members of the Indian Department removed themselves from their homes in what is today the United States and established themselves in Canada as Loyalists. Sir John Johnson became one of the leading men of the Montreal region, while Alexander McKee was one of the founding settlers in western Upper Canada. The migration of the Six Nations of the Grand River with Joseph Brant and the Mohawks of the Bay of Quinte with John Deseronto to the Province of Quebec was part of this movement.[10][12]

A separate head of the Indian Department in Upper Canada, called the Deputy Superintendent General, was created in 1794. Alexander McKee was the first Deputy Superintendent General of Upper Canada, from 1794 until his death in 1799. He was succeeded by William Claus, who served from 1799 until his death in 1826.[15]

War of 1812

The Indian Department again played an important part in the War of 1812, mobilizing warriors to defeat the United States in a number of important battles from Montreal to the Mississippi River.[16] The Indian Department was particularly important in supporting the revival movement led by Tenskwatawa, the Shawnee Prophet, and his brother Tecumseh. Indeed, many members of the Department, like George Ironside Sr. and Matthew Elliott, had family connections to the Shawnee. Other prominent members of the Department during the War of 1812 include Joseph Brant's son, John Brant, Joseph Brant's adopted heir, John Norton, and Sir Willian Johnson's grandson, William Claus.[17][18]

During the War of 1812, a uniform was established for the Indian Department for the first time, consisting of a red jacket faced with green on the collar and cuffs.[19]

One of the primary objectives of the British Indian Department and its First Nations allies was the establishment of an Indian barrier state in American territory that would be both an Indigenous homeland free of American settlers and an extra line of defence for British Canada. The defeat of Tecumseh's confederacy at the Battle of the Thames in 1813 was a heavy blow to this project. However, even after this setback the Indian Department won a number of important victories alongside its Indigenous allies, including the Battle of Michilimackinac and the Siege of Prairie du Chien in the summer of 1814.[20]

Treaty of Ghent

During the war, the British Indian Department made repeated promises that the First Nations would not be abandoned in any peace treaty made with the United States. Despite these assurances, the Treaty of Ghent that ended the war in 1815 did not contain any provision for an Indian barrier state. Similar to the situation after the Treaty of Paris in 1783, the Indigenous communities that had taken up arms as allies of the British were once again abandoned. There is substantial evidence that this betrayal deeply disturbed the members of the British Indian Department. Lieutenant Colonel Robert McDouall, temporarily in charge of the Indian Department at Michilimackinac, wrote many lengthy dispatches decrying the abandonment of Great Britain's Indigenous allies.[21]

Post-war period, 1815-1860

Given the increased military importance of the Indian Department following the War of 1812, the separate branches in Upper and Lower Canada were reunified under the military control of the Commander of the Forces in 1816. In 1830, the Indian Department was again divided into separate Upper and Lower Canadian branches. In the upper province, Lieutenant Governor Sir John Colborne appointed veteran agent James Givins as Chief Superintendent to oversee the Upper Canadian branch. After Givins retired in 1837, he was replaced by Smauel Peters Jarvis.[22] In Lower Canada, Duncan Campbell Napier became the senior member of the Indian Department following the death of Sir John Johnson in 1830. Napier remained at the head of the Indian Department in what is today Quebec until his retirement in 1857.[23]

During the Rebellions of 1837–1838, the Indian Department again mobilized warriors to put down the internal insurrections and the numerous Patriot invasions from American territory.[24]

Transfer to the Canadian government

In 1841, the Canadas were amalgamated into the Province of Canada, and the Governor General assumed direct oversight of the Indian Department. In practice, his secretary handled most of the day-to-day operations of the department. This situation continued until 1860, when the British government transferred responsibility for the Indian Department to the government of the Province of Canada. During the fifteen years leading up to the transfer of the Indian Department, many of its old practises were discarded, including most prominently the annual giving of presents to those Indigenous communities who were in alliance with the British Crown.[25]

Gallery of prominent members

Superintendent General William Johnson (c. 1715-1774)

Superintendent General William Johnson (c. 1715-1774) Colonel Luc de la Corne (1711-1784)

Colonel Luc de la Corne (1711-1784) Deputy Agent Daniel Claus (1727-1787)

Deputy Agent Daniel Claus (1727-1787) Superintendent General Sir John Johnson (1741-1830)

Superintendent General Sir John Johnson (1741-1830) Deputy Agent John Butler (1728-1796)

Deputy Agent John Butler (1728-1796) Deputy Superintendent General William Claus (1765–1826)

Deputy Superintendent General William Claus (1765–1826) Superintendent Thomas McKee (c. 1770-1814)

Superintendent Thomas McKee (c. 1770-1814) Major John Norton (c. 1770 - c. 1830)

Major John Norton (c. 1770 - c. 1830).jpg.webp) Superintendent John Brant (1794-1832)

Superintendent John Brant (1794-1832) Chief Superintendent Samuel Peters Jarvis (1792-1857)

Chief Superintendent Samuel Peters Jarvis (1792-1857)

Rank structure

The Indian Department did not belong to the army but was organized along military lines.[26] During wars, the Department's officers in the field acted as instructors and advisers to the auxiliary forces made available by the First Nations.[27]

| American Revolutionary War | |

|---|---|

| # | Grade |

| Officers | |

| 1 | Superintendent General |

| 2 | Superintendent |

| 3 | Deputy Superintendent |

| 4 | Captain |

| 5 | Commissary |

| 6 | Lieutenant |

| 7 | Translator |

| 8 | Clerk |

| Men | |

| 9 | Volunteer |

| 10 | Private |

| Sources: | [26][28] |

| War of 1812 | |

|---|---|

| # | Grade |

| Commissioned officers | |

| 1 | Superintendent-General and Inspector-General Head of the Department in Lower Canada |

| 2 | Deputy Superintendent-General and Deputy Inspector-General Commanding in Upper Canada |

| 3 | Deputy Agent Second in command in Lower Canada |

| 4 | Superintendent Commanding in the field |

| 5 | Deputy Superintendent Second in command in the field |

| 6 | Secretary |

| Resident Agent Indian Agent in Lower Canada | |

| Agent Inian Agentin Upper Canada | |

| 7 | Assistant Secretary |

| Storekeeper-General | |

| 8 | Surgeon |

| Storekeeper | |

| Resident Agent and Captain Indian Agent and officer in the field in Lower Canada | |

| Resident and Captain Indian Agent and officer in the field in Upper Canada | |

| Captain Officer in the field in Upper Canada | |

| 9 | Lieutenant and Interpreter Interpreter and officer in the field in Lower Canada |

| Lieutenant Officer in the field in Upper Canada | |

| Surgeon's Mate | |

| Warrant officers | |

| 10 | Interpreter |

| Source: | [27] |

See also

References

- ↑ Allen, Robert S. (1993). His Majesty's Indian Allies: British Indian Policy in Defence of Canada. Dundern Press. pp. 167–170.

- 1 2 3 Kawashima, Yasuhide (1988). "Colonial Government Agencies." Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 4: History of Indian-White Relations. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution, pp. 245-254.

- 1 2 3 Douglas Sanders, "Government Indian Agencies in Canada", Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 4: History of Indian-White Relations (Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution, 1988): 276-283.

- ↑ "Sir William Johnson; The Canadian Encyclopedia". Retrieved 16 August 2021.

- ↑ Allen, Robert S. (1975). "The Regime of Sir William Johnson (1755-74)". Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History. Parks Canada. Retrieved 15 September 2021.

- ↑ "American Indians: British Policies". Retrieved 11 September 2020.

- ↑ "Joseph Brant; The Dictionary of Canadian Biography". Retrieved 16 August 2021.

- ↑ "Mary Brant; The Dictionary of Canadian Biography". Retrieved 16 August 2021.

- ↑ Watt, Gavin K.; Morrison, James F. (1997). The Burning of the Valleys: Daring Raids from Canada against the New York Frontier in the Fall of 1780. Toronto: Dundurn Press.

- 1 2 "Alexander McKee; The Dictionary of Canadian Biography". Retrieved 16 August 2021.

- ↑ Nelson, Larry L. (1999). A Man of Distinction among Them: Alexander McKee and the Ohio Country frontier, 1754-1799. Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press. pp. 113–129. ISBN 0873386205.

- 1 2 "Sir John Johnson; The Dictionary of Canadian Biography". Retrieved 16 August 2021.

- ↑ Allen, Robert S. (1975). "Indian Confederacy: The Collapse (1793-96)". Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History. Parks Canada. Retrieved 15 September 2021.

- ↑ Hatter, Lawrence B. (2017). Citizens of Convenience: The Imperial Origins of American Nationhood on the U.S.-Canadian border. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press. p. 11.

- ↑ "William Claus; The Dictionary of Canadian Biography". Retrieved 16 August 2021.

- ↑ Allen, Robert S. (1993). His Majesty's Indian Allies: British Indian Policy in Defence of Canada. Dundern Press. p. 147.

- ↑ Allen, Robert S. (1975). "The Indian Department and the Northwest in the War of 1812 (1807-15)". Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History. Parks Canada. Retrieved 15 September 2021.

- ↑ "John Brant; The Dictionary of Canadian Biography". Retrieved 16 August 2021.

- ↑ Irving, L. Homfray (1908). Officers of the British Forces in Canada During the War of 1812-15. Canadian Military Institute. Retrieved 2017-02-10.

- ↑ Allen, Robert S. (1975). "The Indian Department and the Northwest in the War of 1812 (1807-15)". Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History. Parks Canada. Retrieved 15 September 2021.

- ↑ "Robert McDouall; The Dictionary of Canadian Biography". Retrieved 16 August 2021.

- ↑ "Samuel Peters Jarvis; The Dictionary of Canadian Biography". Retrieved 16 August 2021.

- ↑ "Duncan Campbell Napier; The Dictionary of Canadian Biography". Retrieved 16 August 2021.

- ↑ Allen, Robert S. (1993). His Majesty's Indian Allies: British Indian Policy in Defence of Canada. Dundern Press. p. 184.

- ↑ Leslie, John F. (1985). Commissions of Inquiry into Indian Affairs in the Canadas, 1828-1858: Evolving a Corporate Memory for the Indian Department (Report). Indian and Northern Affairs Canada. p. 132.

- 1 2 Chartrand, Renee (2008). American Loyalist Troops 1775-1784. Osprey Publishing, pp. 18-19, 22, 24, 43.

- 1 2 Homfray Irving, L. (1908). Officers of the British Forces in Canada during the War of 1812. Welland Tribune Print, p. 208-216.

- ↑ "Indian Department.List of Men. Loyalist Institute. Retrieved December 27, 2021.