| This article is part of the series on the |

| Italian language |

|---|

| History |

| Literature and other |

| Grammar |

| Alphabet |

| Phonology |

The phonology of Italian describes the sound system—the phonology and phonetics—of Standard Italian and its geographical variants.

Consonants

| Labial | Dental/ alveolar |

Post- alveolar/ palatal |

Velar | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | |||||

| Stop | p | b | t | d | k | ɡ | ||

| Affricate | t͡s | d͡z | t͡ʃ | d͡ʒ | ||||

| Fricative | f | v | s | z | ʃ | (ʒ) | ||

| Approximant | j | w | ||||||

| Lateral | l | ʎ | ||||||

| Trill | r | |||||||

Notes:

- Between two vowels, or between a vowel and an approximant (/j, w/) or a liquid (/l, r/), consonants can be both singleton or geminated. Geminated consonants shorten the preceding vowel (or block phonetic lengthening) and the first geminated element is unreleased. For example, compare /fato/ [ˈfaːto] ('fate') with /fatto/ [ˈfat̚to] ('fact').[1] However, /ɲ/, /ʃ/, /ʎ/, /d͡z/, /t͡s/ are always geminated intervocalically, including across word boundaries.[2] Similarly, nasals, liquids, and sibilants are pronounced slightly longer in medial consonant clusters.[3]

- /j/, /w/, and /z/ are the only consonants that cannot be geminated.

- /t, d/ are laminal denti-alveolar [t̪, d̪],[4][5][2] commonly called "dental" for simplicity.

- /k, ɡ/ are pre-velar before /i, e, ɛ, j/.[5]

- /t͡s, d͡z, s, z/ have two variants:

- Dentalized laminal alveolar [t̪͡s̪, d̪͡z̪, s̪, z̪][4][6] (commonly called "dental" for simplicity), pronounced with the blade of the tongue very close to the upper front teeth, with the tip of the tongue resting behind lower front teeth.[6]

- Non-retracted apical alveolar [t͡s̺, d͡z̺, s̺, z̺].[6] The stop component of the "apical" affricates is actually laminal denti-alveolar.[6]

- /n, l, r/ are apical alveolar [n̺, l̺, r̺] in most environments.[4][2][7] /n, l/ are laminal denti-alveolar [n̪, l̪] before /t, d, t͡s, d͡z, s, z/[2][8][9] and palatalized laminal postalveolar [n̠ʲ, l̠ʲ] before /t͡ʃ, d͡ʒ, ʃ/.[10][11] /n/ is velar [ŋ] before /k, ɡ/.[12][13]

- /m/ and /n/ do not contrast before /p, b/ and /f, v/, where they are pronounced [m] and [ɱ], respectively.[12][14]

- /ɲ/ and /ʎ/ are alveolo-palatal.[15] In a large number of accents, /ʎ/ is a fricative [ʎ̝].[16]

- Intervocalically, single /r/ is realised as a trill with one or two contacts.[17] Some literature treats the single-contact trill as a tap [ɾ].[18][19] Single-contact trills can also occur elsewhere, particularly in unstressed syllables.[20] Geminate /rr/ manifests as a trill with three to seven contacts.[17]

- The phonemic distinction between /s/ and /z/ is neutralized before consonants and at the beginning of words: the former is used before voiceless consonants and before vowels at the beginning of words; the latter is used before voiced consonants. The two can contrast only between vowels within a word, e.g. fuso /ˈfuzo/ 'melted' versus fuso /ˈfuso/ 'spindle'. According to Canepari,[19] though, the traditional standard has been replaced by a modern neutral pronunciation which always prefers /z/ when intervocalic, except when the intervocalic s is the initial sound of a word, if the compound is still felt as such: for example, presento /preˈsɛnto/[21] ('I foresee', with pre- meaning 'before' and sento meaning 'I perceive') vs presento /preˈzɛnto/[22] ('I present'). There are many words for which dictionaries now indicate that both pronunciations, either [z] or [s], are acceptable. Word-internally between vowels, both phonemes have merged in many regional varieties of Italian, as either /z/ (Northern-Central) or /s/ (Southern-Central).

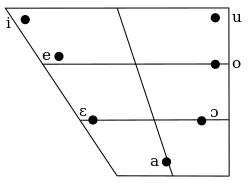

Vowels

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i | u | |

| Close-mid | e | o | |

| Open-mid | ɛ | ɔ | |

| Open | a |

In Italian phonemic distinction between long and short vowels is rare and limited to a few words and one morphological class, namely the pair composed by the first and third person of the historic past in verbs of the third conjugation – compare sentii (/senˈtiː/, "I felt/heard'), and sentì (/senˈti/, "he felt/heard").

Normally vowels in stressed open syllables, unless word-final, are long at the end of the intonational phrase (including isolated words) or when emphasized.[23][24] Adjacent identical vowels found at morpheme boundaries are not resyllabified, but pronounced separately ("quickly rearticulated"), and they might be reduced to a single short vowel in rapid speech.[25]

Although Italian contrasts close-mid (/e, o/) and open-mid (/ɛ, ɔ/) vowels in stressed syllables, the distinction is neutralised in unstressed position[23] in which only the close-mid vowels occur. The height of such vowels in unstressed position is context-sensitive; they are somewhat lowered ([e̞, o̞]) in the vicinity of more open vowels.[26] The distinction between close-mid and open-mid vowels is lost entirely in a few Southern varieties of Regional Italian, especially in Northern Sicily (e.g. Palermo), where they are realized as open-mid [ɛ, ɔ], as well as in some Northern varieties (in particular in Piedmont), where they are realized as mid [e̞, o̞].

Word-final stressed /ɔ/ is found in a small number of words: però, ciò, paltò.[27] However, as a productive morpheme, it marks the first person singular of all future tense verbs (e.g. dormirò 'I will sleep') and the third person singular preterite of first conjugation verbs (parlò 's/he spoke', but credé 's/he believed', dormì 's/he slept'). Word-final unstressed /u/ is rare, [28] found in onomatopoeic terms (babau),[29] loanwords (guru),[30] and place or family names derived from the Sardinian language (Gennargentu,[31] Porcu).[32]

When the last phoneme of a word is an unstressed vowel and the first phoneme of the following word is any vowel, the former vowel tends to become non-syllabic. This phenomenon is called synalepha and should be taken into account when counting syllables, e.g. in poetry.

In addition to monophthongs, Italian has diphthongs, which, however, are both phonemically and phonetically simply combinations of the other vowels. Some are very common (e.g. /ai, au/), others are rarer (e.g. /ɛi/) and some never occur within native Italian words (e.g. /ou/). None of the diphthongs are, however, considered to have distinct phonemic status since their constituents do not behave differently from how they occur in isolation, unlike the diphthongs in other languages like English and German. Grammatical tradition distinguishes 'falling' from 'rising' diphthongs, but since rising diphthongs are composed of one semiconsonantal sound [j] or [w] and one vowel sound, they are not actually diphthongs. The practice of referring to them as 'diphthongs' has been criticised by phoneticians like Luciano Canepari.[19]

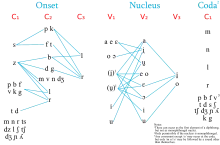

Phonotactics

Onset

Italian allows up to three consonants in syllable-initial position, though there are limitations:[33]

CC

- /s/ + any voiceless stop or /f/. E.g. spavento ('fright')

- /z/ + any voiced stop, /v d͡ʒ m n l r/. E.g. srotolare ('unroll')

- /f v/, or any stop + /r/. E.g. frana ('landslide')

- /f v/, or any stop except /t d/ + /l/. E.g. platano ('planetree')

- /f v s z/, or any stop or nasal + /j w/. E.g. fiume ('river'), vuole ('he/she wants'), siamo ('we are'), suono ('sound')

- In words of foreign (mostly Greek) origin which are only partially assimilated, other combinations such as /pn/ (e.g. pneumatico), /mn/ (e.g. mnemonico), /tm/ (e.g. tmesi), and /ps/ (e.g. pseudo-) occur.

As an onset, the cluster /s/ + voiceless consonant is inherently unstable. Phonetically, word-internal s+C normally syllabifies as [s.C]: [ˈrɔs.po] rospo 'toad', [tras.ˈteː.ve.re] Trastevere (neighborhood of Rome).[34][35] Phonetic syllabification of the cluster also occurs at word boundaries if a vowel precedes it without pause, e.g. [las.ˈtɔː.rja] la storia 'the history', implying the same syllable break at the structural level, /sˈtɔrja/,[36] thus always latent due to the extrasyllabic /s/, but unrealized phonetically unless a vowel precedes.[37] A competing analysis accepts that while the syllabification /s.C/ is accurate historically, modern retreat of i-prosthesis before word initial /s/+C (e.g. erstwhile con isforzo 'with effort' has generally given way to con sforzo) suggests that the structure is now underdetermined, with occurrence of /s.C/ or /.sC/ variable "according to the context and the idiosyncratic behaviour of the speakers."[38]

CCC

- /s/ + voiceless stop or /f/ + /r/. E.g. spregiare ('to despise')

- /z/ + voiced stop + /r/. E.g. sbracciato ('with bare arms'), sdraiare ('to lay down'), sgravare ('to relieve')

- /s/ + /p k/ + /l/. E.g. sclerosi ('sclerosis')

- /z/ + /b/ + /l/. E.g. sbloccato ('unblocked')

- /f v/ or any stop + /r/ + /j w/. E.g. priego (antiquated form of prego 'I pray'), proprio ('(one's) own' / proper / properly), pruovo (antiquated form of provo 'I try')

- /f v/ or any stop or nasal + /w/ + /j/. E.g. quieto ('quiet'), continuiamo ('we continue')

The last combination is however rare and one of the approximants is often vocalised, e.g. quieto /kwiˈɛto,ˈkwjɛto/, continuiamo /kontinuˈjamo, kontinwiˈamo, ((kontiˈnwjamo))/

Nucleus

The nucleus is the only mandatory part of a syllable (for instance, a 'to, at' is a word) and must be a vowel or a diphthong. In a falling diphthong the most common second elements are /i̯/ or /u̯/ but other combinations such as idea /iˈdɛa̯/, trae /ˈtrae̯/ may also be interpreted as diphthongs.[19] Combinations of /j w/ with vowels are often labelled diphthongs, allowing for combinations of /j w/ with falling diphthongs to be called triphthongs. One view holds that it is more accurate to label /j w/ as consonants and /jV wV/ as consonant-vowel sequences rather than rising diphthongs. In that interpretation, Italian has only falling diphthongs (phonemically at least, cf. Synaeresis) and no triphthongs.[19]

| VP2 | VP1 | VC | VD | VP | VC | VC | VD | VC | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| j | a | i̯ | j | a | a | i̯ | a | ||||

| ɛ | ɛ | ɛ | - | ||||||||

| i̯ɛ | - | ||||||||||

| ɔ | ɔ | ɔ | ɔ | ||||||||

| u̯ɔ | u̯ɔ | u̯ɔ | |||||||||

| (k/g)w | a | (k/g)w | a | a | u̯ | - | |||||

| ɛ | ɛ | ɛ | ɛ | ||||||||

| i̯ɛ | i̯ɛ | ||||||||||

| ɔ | ɔ | ɔ | - | ||||||||

| - | - | ||||||||||

| j | e | e | i̯ | o | |||||||

| o | o | (u̯o) | |||||||||

| u | u | u | |||||||||

| (k/g)w | e | e | u̯ | e | |||||||

| o | o | (i̯e) | |||||||||

| i | i | i | |||||||||

| (k/g)w | j | a | - | ||||||||

| i̯ | |||||||||||

| ɛ | - | ||||||||||

| - | - | ||||||||||

| - | - | ||||||||||

| o | - | ||||||||||

Coda

Italian permits a small number of coda consonants. Outside of loanwords,[39] the permitted consonants are:

- The first element of any geminate,[40] e.g. tutto ('everything'), avvertire ('to warn').

- A nasal consonant that is either /n/ (word-finally) or one that is homorganic to a following consonant.[40] E.g. Con ('with'), un poco [umˈpɔːko] ('a little'), ampio ('ample').

- Liquid consonants /r/ and /l/.[40] E.g. per ('for'), alto ('high').

- /s/ (though not before fricatives).[41] E.g. pesca ('peach'); but asfalto ('asphalt').

There are also restrictions in the types of syllables that permit consonants in the syllable coda. Krämer (2009) explains that neither geminates, nor coda consonants with "rising sonority" can follow falling diphthongs. However, "rising diphthongs" (or sequences of an approximant and a following vowel) may precede clusters with falling sonority, particularly those that stem historically from an obstruent+liquid onset.[42] For example:[43]

- biondo ('blond')

- chiosco ('kiosk')

- chiostro ('cloister')

- chioccia ('broody hen')

- fianco ('hip')

Syntactic gemination

Word-initial consonants are geminated after certain vowel-final words in the same prosodic unit. There are two types of triggers of initial gemination: some unstressed particles, prepositions, and other monosyllabic words, and any oxytonic polysyllabic word.[35] As an example of the first type, casa ('house') is pronounced [ˈkaːza] but a casa ('homeward') is pronounced [akˈkaːza]. This is not a purely phonological process, as no gemination is cued by the la in la casa 'the house' [laˈkaːza], and there is nothing detectable in the structure of the preposition a to account for the gemination. This type normally originates in language history: modern a, for example, derives from Latin AD, and today's geminate in [akˈkaːza] is a continuation of what was once a simple assimilation. Gemination cued by final stressed vowels, however, is transparently phonological. Final stressed vowels are short by nature, if a consonant follows a short stressed vowel the syllable must be closed, thus the consonant following the final stressed vowel is drawn to lengthen: parlò portoghese [parˈlɔpportoˈɡeːze] 's/he spoke Portuguese' vs. parla portoghese [ˈparlaportoˈɡeːze] 's/he speaks Portuguese'.

To summarize, syntactic gemination occurs in standard Italian mainly in the following two cases:[44]

- After word-final stressed vowels (words such as sanità, perché, poté, morì and so on).

- After the words a, che, chi, come, da, do, dove, e, fa, fra, fu, gru, ha, ho, ma, me, mo' (in the phrase a mo' di), no, o, qua, qualche, qui, so, sopra, sta, sto, su, te, tra, tre, tu, va, vo.

Syntactic gemination is the normal native pronunciation in Central Italy (both "stress-induced" and "lexical") and Southern Italy (only "lexical"), including Sicily and Corsica (France).

In Northern Italy and Sardinia, speakers use it inconsistently because the feature is not present in the dialectal substratum and is not usually shown in the written language unless a new word is produced by the fusion of the two: "chi sa"-> chissà ("who knows" in the sense of goodness knows).

Regional variation

The above IPA symbols and description refer to standard Italian, based on a somewhat idealized version of the Tuscan-derived national language. As is common in many cultures, this single version of the language was pushed as neutral, proper, and eventually superior, leading to some stigmatization of varying accents. Television news anchors and other high-profile figures had to put aside their regional Italian when in the public sphere. However, in more recent years the enforcement of this standard has fallen out of favor in Italy, and news reporters, actors, and the like are now more free to deliver their words in their native regional variety of Italian, which appeals to the Italian population's range of linguistic diversity. The variety is still not represented in its wholeness and accents from the South are maybe to be considered less popular, except in shows set in the South and in comedy, a field in which Naples, Sicily and the South in general have always been present. Though it still represents the basics for the standard variety, the loosened restrictions have led to Tuscan being seen for what it is, just one dialect among many with its own regional peculiarities and qualities, many of which are shared with Umbria, Southern Marche and Northern Lazio.

- In Tuscany (though not in standard Italian, which is derived from, but not equivalent to, Tuscan dialect), voiceless stops are typically pronounced as fricatives between vowels.[45] That is, /p t k/ → [ɸ θ h/x]: e.g. i capitani 'the captains' [iˌhaɸiˈθaːni], a phenomenon known as the gorgia toscana 'Tuscan throat'. In a much more widespread area of Central Italy, postalveolar affricates are deaffricated when intervocalic so that in Cina ('in China') is pronounced [in t͡ʃiːna] but la Cina ('the China') is [laʃiːna], and /ˈbat͡ʃo/ bacio 'kiss' is [ˈbaːʃo] rather than Standard Italian [ˈbaːt͡ʃo].[46] This deaffrication can result in minimal pairs distinguished only by length of the fricatives, [ʃ] issuing from /t͡ʃ/ and [ʃː] from geminate /ʃʃ/: [laʃeˈrɔ] lacerò 's/he ripped' vs. [laʃːeˈrɔ] lascerò 'I will leave'.

- In nonstandard varieties of Central and Southern Italian, some stops at the end of a syllable completely assimilate to the following consonant. For example, a Venetian might say tecnica as [ˈtɛknika] or [ˈtɛɡnika] in violation of normal Italian consonant contact restrictions, while a Florentine would likely pronounce tecnica as [ˈtɛnniha], a Roman on a range from [ˈtɛnnika] to [ˈtɛnniɡa] (in Southern Italian, complex clusters usually are separated by a vowel: a Neapolitan would say [ˈtɛkkənikə], a Sicilian [ˈtɛkkɪnɪka]). Similarly, although the cluster /kt/ has developed historically as /tt/ through assimilation, a learned word such as ictus will be pronounced [ittus] by some, [iktus] by others.

- In popular (non-Tuscan) Central and Southern Italian speech, /b/ and /d͡ʒ/ tend to always be geminated ([bb] and [dd͡ʒ]) when between two vowels, or a vowel and a sonorant (/j/, /w/, /l/, or /r/). Sometimes this is also used in written language, e.g. writing robba instead of roba ('property'), to suggest a regional accent, though this spelling is considered incorrect. In Tuscany and beyond in Central and Southern Italy, intervocalic non-geminate /d͡ʒ/ is realized as [ʒ] (parallel to /t͡ʃ/ realized as [ʃ] described above).

- The two phonemes /s/ and /z/ have merged in many varieties of Italian: when between two vowels within the same word, it tends to always be pronounced [z] in Northern Italy, and [s] in Central and Southern Italy (except in the Arbëreshë community). A notable example is the word casa ('house'): in Northern Italy it is pronounced [ˈkaːza]; in Southern-Central Italy it is pronounced [ˈkaːsa].

- In several Southern varieties, voiceless stops tend to be voiced if following a sonorant, as an influence of the still largely spoken regional languages: campo /ˈkampo/ is often pronounced [ˈkambo], and Antonio /anˈtɔnjo/ is frequently [anˈdɔnjo].

The various Tuscan, Corsican and Central Italian dialects are, to some extent, the closest ones to Standard Italian in terms of linguistic features, since the latter is based on a somewhat polished form of Florentine.

Phonological development

Very little research has been done on the earliest stages of phonological development in Italian.[47] This article primarily describes phonological development after the first year of life. See the main article on phonological development for a description of first year stages. Many of the earliest stages are thought to be universal to all infants.

Phoneme inventory

Word-final consonants are rarely produced during the early stages of word production. Consonants are usually found in word-initial position, or in intervocalic position.[48]

17 months

Most consonants are word-initial: They are the stops /p/, /b/, /t/, and /k/ and the nasal /m/. A preference for a front place of articulation is present.

21 months

More phones now appear in intervocalic contexts. The additions to the phonetic inventory are the voiced stop /d/, the nasal /n/, the voiceless affricate /t͡ʃ/, and the liquid /l/.[48]

24 months

The fricatives /f/, /v/, and /s/ are added, primarily at the intervocalic position.[48]

27 months

Approximately equal numbers of phones are now produced in word-initial and intervocalic position. Additions to the phonetic inventory are the voiced stop /ɡ/ and the consonant cluster /kw/. While the word-initial inventory now tends to have all the phones of the adult targets (adult production of the child's words), the intervocalic inventory tends to still be missing four consonants or consonant clusters of the adult targets: /f/, /d͡ʒ/, /r/, and /st/.[48]

Stops are the most common manner of articulation at all stages and are produced more often than they are present in the target words at around 18 months. Gradually this frequency decreases to almost target-like frequency by around 27 months. The opposite process happens with fricatives, affricates, laterals and trills. Initially, the production of these phonemes is significantly less than what is found in the target words and the production continues to increases to target-like frequency. Alveolars and bilabials are the two most common places of articulation, with alveolar production steadily increasing after the first stage and bilabial production gently decreasing. Labiodental and postalveolar production increases throughout development, while velar production decreases.[49]

Phonotactics

Syllable structures

6–10 months

Babbling becomes distinct from previous, less structured vocal play. Initially, syllable structure is limited to CVCV, called reduplicated babbling. At this stage, children's vocalizations have a weak relation to adult Italian and the Italian lexicon.[50]

11–14 months

The most-used syllable type changes as children age, and the distribution of syllables takes on increasingly Italian characteristics. This ability significantly increases between the ages of 11 and 12 months, 12 and 13 months, and 13 and 14 months.[50] Consonant clusters are still absent. Children's first ten words appear around month 12, and take CVCV format (e.g. mamma 'mom', papà 'dad').[51]

18–24 months

Reduplicated babbling is replaced by variegated babbling, producing syllable structures such as C1VC2V (e.g. cane 'dog', topo 'mouse'). Production of trisyllabic words begins (e.g. pecora 'sheep', matita 'pencil').[51] Consonant clusters are now present (e.g. bimba 'female child', venti 'twenty'). Ambient language plays an increasingly significant role as children begin to solidify early syllable structure. Syllable combinations that are infrequent in the Italian lexicon, such as velar-labial sequences (e.g. capra 'goat' or gamba 'leg') are infrequently produced correctly by children, and are often subject to consonant harmony.[52]

Stress patterns

In Italian, stress is lexical, meaning it is word-specific and partly unpredictable. Penultimate stress (primary stress on the second-to-last syllable) is also generally preferred.[53][54] This goal, acting simultaneously with the child's initial inability to produce polysyllabic words, often results in weak-syllable deletion. The primary environment for weak-syllable deletion in polysyllabic words is word-initial, as deleting word-final or word-medial syllables would interfere with the penultimate stress pattern heard in ambient language.[55]

Phonological awareness

Children develop syllabic segmentation awareness earlier than phonemic segmentation awareness. In earlier stages, syllables are perceived as a separate phonetic unit, while phonemes are perceived as assimilated units by coarticulation in spoken language. By first grade, Italian children are nearing full development of segmentation awareness on both syllables and phonemes. Compared to those children whose mother tongue exhibits closed syllable structure (CVC,CCVC, CVCC, etc.), Italian-speaking children develop this segmentation awareness earlier, possibly due to its open syllable structure (CVCV, CVCVCV, etc.).[56] Rigidity in Italian (shallow orthography and open syllable structure) makes it easier for Italian-speaking children to be aware of those segments.[57]

Sample texts

Provided here is a rendition of the Bible, Luke 2, 1–7, as read by a native Italian speaker from Milan. As a northerner, his pronunciation lacks syntactic doubling ([ˈfu ˈfatto] instead of [ˈfu fˈfatto]) and intervocalic [s] ([ˈkaːza] instead of [ˈkaːsa]). The speaker realises /r/ as [ʋ] in some positions.

2:1 In quei giorni, un decreto di Cesare Augusto ordinava che si facesse un censimento di tutta la terra.

2 Questo primo censimento fu fatto quando Quirino era governatore della Siria.

3 Tutti andavano a farsi registrare, ciascuno nella propria città.

4 Anche Giuseppe, che era della casa e della famiglia di Davide, dalla città di Nazaret e dalla Galilea si recò in Giudea nella città di Davide, chiamata Betlemme,

5 per farsi registrare insieme a Maria, sua sposa, che era incinta.

6 Proprio mentre si trovavano lì, venne il tempo per lei di partorire.

7 Mise al mondo il suo primogenito, lo avvolse in fasce e lo depose in una mangiatoia, poiché non c'era posto per loro nella locanda.

The differences in pronunciation are underlined in the following transcriptions; the velar [ŋ] is an allophone of /n/ and the long vowels are allophones of the short vowels, but are shown for clarity.

A rough transcription of the audio sample is:

2:1 [iŋ ˈkwɛi ˈdʒorni un deˈkreːto di ˈtʃeːzare auˈɡusto ordiˈnaːva ke si faˈtʃɛsːe un tʃensiˈmento di ˈtutːa la ˈtɛrːa

2 ˈkwɛsto ˈpriːmo tʃensiˈmento fu ˈfatːo ˈkwando kwiˈriːno ˈeːra ɡovernaˈtoːre dɛlːa ˈsiːrja

3 ˈtutːi anˈdaːvano a ˈfarsi redʒiˈstraːre tʃaˈskuːno nɛlːa ˈprɔːprja tʃiˈtːa

4 ˈaŋke dʒuˈzɛpːe ke ˈeːra dɛlːa ˈkaːza e dɛlːa faˈmiʎːa di ˈdaːvide dalːa tʃiˈtːa di ˈnadzːaret e dalːa ɡaliˈleːa si reˈkɔ in dʒuˈdeːa nɛlla tʃiˈtːa di ˈdaːvide kjaˈmaːta beˈtlɛmːe

5 per ˈfarsi redʒiˈstraːre inˈsjeːme a maˈriːa swa ˈspoːza ke ˈeːra inˈtʃinta

6 ˈprɔːprjo ˈmentre si troˈvaːvano ˈli ˈvɛnːe il ˈtempo per ˈlɛi di partoˈriːre

7 ˈmiːze al ˈmondo il swo primoˈdʒeːnito, lo aˈvːɔlse iɱ ˈfaːʃe e lo deˈpoːze in ˈuːna mandʒaˈtɔːja poiˈke non ˈtʃeːra ˈpɔsto per ˈloːro nɛlːa loˈkanda]

The Standard Italian pronunciation of the text is:

2:1 [iŋ ˈkwei ˈdʒorni un deˈkreːto di ˈtʃeːzare auˈɡusto ordiˈnaːva ke sːi faˈtʃesːe un tʃensiˈmento di ˈtutːa la ˈtɛrːa

2 ˈkwesto ˈpriːmo tʃensiˈmento fu ˈfːatːo ˈkwando kwiˈriːno ˈɛːra ɡovernaˈtoːre delːa ˈsiːrja

3 ˈtutːi anˈdaːvano a ˈfːarsi redʒiˈstraːre tʃaˈskuːno nelːa ˈprɔːprja tʃiˈtːa

4 ˈaŋke dʒuˈzɛpːe ke ˈɛːra delːa ˈkaːsa e dːelːa faˈmiʎːa di ˈdaːvide dalːa tʃiˈtːa dːi ˈnadzːaret e dːalːa ɡaliˈlɛːa si reˈkɔ in dʒuˈdɛːa nelːa tʃiˈtːa dːi ˈdaːvide kjaˈmaːta beˈtlɛmːe

5 per ˈfarsi redʒiˈstraːre inˈsjɛːme a mːaˈriːa ˈsuːa ˈspɔːza ke ˈɛːra inˈtʃinta

6 ˈprɔːprjo ˈmentre si troˈvaːvano ˈli ˈvenːe il ˈtɛmpo per ˈlɛi di partoˈriːre

7 ˈmiːse al ˈmondo il ˈsuːo primoˈdʒɛːnito, lo aˈvːɔlse iɱ ˈfaʃːe e lːo deˈpoːse in ˈuːna mandʒaˈtoːja poiˈke nːon ˈtʃɛːra ˈposto per ˈloːro nelːa loˈkanda]

See also

- Italian orthography

- Italian language

- Italian grammar

- Syntactic gemination

- Wikipedia help page for IPA for Italian – includes English approximations

- Italian pronunciation guide at Wiktionary

References

- ↑ Hall (1944), pp. 77–78.

- 1 2 3 4 Rogers & d'Arcangeli (2004), p. 117.

- ↑ Hall (1944), p. 78.

- 1 2 3 Bertinetto & Loporcaro (2005), p. 132.

- 1 2 Canepari (1992), p. 62.

- 1 2 3 4 Canepari (1992), pp. 68, 75–76.

- ↑ Canepari (1992), pp. 57, 84, 88–89.

- ↑ Bertinetto & Loporcaro (2005), p. 133.

- ↑ Canepari (1992), pp. 58, 88–89.

- ↑ Bertinetto & Loporcaro (2005), p. 134.

- ↑ Canepari (1992), pp. 57–59, 88–89.

- 1 2 Bertinetto & Loporcaro (2005), pp. 134–135.

- ↑ Canepari (1992), p. 59.

- ↑ Canepari (1992), p. 58.

- ↑ Recasens (2013), p. 13.

- ↑ "(...) in a large number of Italian accents, there is considerable friction involved in the pronunciation of [ʎ], creating a voiced palatal lateral fricative (for which there is no established IPA symbol)" Ashby (2011:64).

- 1 2 Ladefoged & Maddieson (1996), p. 221.

- ↑ Rogers & d'Arcangeli (2004), p. 118.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Luciano Canepari, A Handbook of Pronunciation, chapter 3: «Italian».

- ↑ Romano, Antonio. "A preliminary contribution to the study of phonetic variation of /r/ in Italian and Italo-Romance." Rhotics. New data and perspectives (Proc. of’r-atics-3, Libera Università di Bolzano (2011): 209–226, pp. 213–214.

- ↑ "Dizionario d'ortografia e di pronunzia". Archived from the original on 2011-07-22. Retrieved 2009-12-12.

- ↑ "Dizionario d'ortografia e di pronunzia". Archived from the original on 2011-07-22. Retrieved 2009-12-12.

- 1 2 Rogers & d'Arcangeli (2004), p. 119.

- ↑ Bertinetto & Loporcaro (2005), p. 136.

- ↑ Bertinetto & Loporcaro (2005), p. 137.

- ↑ Bertinetto & Loporcaro (2005), pp. 137–138.

- ↑ "paltò". www.treccani.it (in Italian). Vocabolario – Treccani.

- ↑ Bertinetto & Loporcaro (2005), p. 138.

- ↑ "Dizionario d'ortografia e di pronunzia". Archived from the original on 2009-07-13. Retrieved 2008-09-01.

- ↑ "Dizionario d'ortografia e di pronunzia". Archived from the original on 2009-07-13. Retrieved 2008-09-01.

- ↑ "Dizionario d'ortografia e di pronunzia". Archived from the original on 2009-07-13. Retrieved 2008-09-01.

- ↑ "Dizionario d'ortografia e di pronunzia". Archived from the original on 2009-07-13. Retrieved 2008-09-01.

- ↑ Hall (1944), p. 79.

- ↑ "Sibilanti in "Enciclopedia dell'Italiano"".

- 1 2 Hall (1944), p. 80.

- ↑ Luciano Canepari, A Handbook of Pronunciation, Chapter 3: "Italian", pp. 135–36

- ↑ "acoustic data confirm the fact that [|sˈtV] /|sˈtV/ (after a pause, or 'silence') is part of the same syllable (a little particular, possibly, on the scale of syllabicity, but nothing really surprising) whereas, obviously, [VsˈtV] /VsˈtV/ constitute two phono-syllables bordering between two C" Luciano Canepari, A Handbook of Pronunciation, Chapter 3: "Italian", p. 136.

- ↑ Bertinetto & Loporcaro (2005), p. 141.

- ↑ Krämer (2009), pp. 138, 139.

- 1 2 3 Krämer (2009), p. 138.

- ↑ Krämer (2009), pp. 138, 141.

- ↑ Krämer (2009), p. 135.

- ↑ Examples come from Krämer (2009:136)

- ↑ thebigbook-2ed, p. 111

- ↑ Hall (1944), p. 75.

- ↑ Hall (1944), p. 76.

- ↑ Keren-Portnoy, Majorano & Vihman (2009), p. 240.

- 1 2 3 4 Zmarich & Bonifacio (2005), p. 759.

- ↑ Zmarich & Bonifacio (2005), p. 760.

- 1 2 Majorano & D'Odorico (2011), p. 53.

- 1 2 Fasolo, Majorano & D'Odorico (2006), p. 86.

- ↑ Majorano & D'Odorico (2011), p. 58.

- ↑ "Stress in Italian occurs most often on the penultimate syllable (paroxytones); it also occurs on the antepenultimate syllable (proparoxytones) ...Borrelli (2002:8).

- ↑ D'Imperio & Rosenthall (1999), p. 5.

- ↑ Majorano & D'Odorico (2011), p. 61.

- ↑ Cossu et al. (1988), p. 10.

- ↑ Cossu et al. (1988), p. 11.

Bibliography

- Ashby, Patricia (2011), Understanding Phonetics, Understanding Language series, Routledge, ISBN 978-0340928271

- Berloco, Fabrizio (2018). The Big Book of Italian Verbs: 900 Fully Conjugated Verbs in All Tenses. With IPA Transcription, 2nd Edition. Lengu. ISBN 978-8894034813.

- Bertinetto, Pier Marco; Loporcaro, Michele (2005). "The sound pattern of Standard Italian, as compared with the varieties spoken in Florence, Milan and Rome" (PDF). Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 35 (2): 131–151. doi:10.1017/S0025100305002148. S2CID 6479830.

- Borrelli, Doris (2002), Raddoppiamento Sintattico in Italian: A Synchronic and Diachronic Cross-Dialectical Study, Outstanding dissertations in linguistics, New York: Psychology Press, ISBN 978-0415942072

- Canepari, Luciano (1992), Il MªPi – Manuale di pronuncia italiana [Handbook of Italian Pronunciation] (in Italian), Bologna: Zanichelli, ISBN 978-88-08-24624-0

- Cossu, Giuseppe; Shankweiler, Donald; Liberman, Isabelle Y.; Katz, Leonard; Tola, Giuseppe (1988). "Awareness of phonological segments and reading ability in Italian children". Applied Psycholinguistics. 9 (1): 1–16. doi:10.1017/S0142716400000424. S2CID 13181948.

- Costamagna, Lidia (2007). "The acquisition of Italian L2 affricates: The case of a Brazilian learner" (PDF). New Sounds: Proceedings of the Fifth International Symposium on the Acquisition of Second Language Speech. pp. 138–148.

- D'Imperio, Mariapaola; Rosenthall, Sam (1999). "Phonetics and phonology of main stress in Italian". Phonology. 16 (1): 1–28. doi:10.1017/S0952675799003681. JSTOR 4420141.

- Fasolo, Mirco; Majorano, Marinella; D'Odorico, Laura (2006). "Babbling and first words in children with slow expressive development" (PDF). Clinical Linguistics & Phonetics. 22 (2): 83–94. doi:10.1080/02699200701600015. hdl:10281/2219. PMID 17896213. S2CID 433081.

- Hall, Robert A. Jr. (1944). "Italian phonemes and orthography". Italica. 21 (2): 72–82. doi:10.2307/475860. JSTOR 475860.

- Keren-Portnoy, Tamar; Majorano, Marinella; Vihman, Marilyn M. (2009). "From phonetics to phonology: The emergence of first words in Italian" (PDF). Journal of Child Language. 36 (2): 235–267. doi:10.1017/S0305000908008933. PMID 18789180. S2CID 3119762.

- Krämer, Martin (2009). The Phonology of Italian. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199290796.

- Ladefoged, Peter; Maddieson, Ian (1996). The Sounds of the World's Languages. Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-19815-6.

- Majorano, Marinella; D'Odorico, Laura (2011). "The transition into ambient language: A longitudinal study of babbling and first word production of Italian children". First Language. 31 (1): 47–66. doi:10.1177/0142723709359239. S2CID 143677144.

- Recasens, Daniel (2013), "On the articulatory classification of (alveolo)palatal consonants" (PDF), Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 43 (1): 1–22, doi:10.1017/S0025100312000199, S2CID 145463946, archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-05-06, retrieved 2019-03-21

- Rogers, Derek; d'Arcangeli, Luciana (2004). "Italian" (PDF). Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 34 (1): 117–121. doi:10.1017/S0025100304001628. S2CID 232345223.

- Zmarich, Claudio; Bonifacio, Serena (2005). "Phonetic Inventories in Italian Children aged 18-27 months: a Longitudinal Study" (PDF). Interspeech. pp. 757–760.