Jeremiah Denton | |

|---|---|

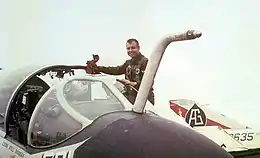

.jpg.webp) Denton in 1983 | |

| United States Senator from Alabama | |

| In office January 2, 1981 – January 3, 1987 | |

| Preceded by | Donald Stewart |

| Succeeded by | Richard Shelby |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Jeremiah Andrew Denton Jr. July 15, 1924 Mobile, Alabama, U.S. |

| Died | March 28, 2014 (aged 89) Virginia Beach, Virginia, U.S. |

| Resting place | Arlington National Cemetery |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouses | Jane Maury

(m. 1946; died 2007)Mary Bordone (m. 2010) |

| Children | 7, including James |

| Education | United States Naval Academy (BS) George Washington University (MA) |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | United States of America |

| Branch/service | United States Navy |

| Years of service | 1946–1977 |

| Rank | Rear admiral |

| Battles/wars | Vietnam War |

| Awards | Navy Cross Defense Distinguished Service Medal Navy Distinguished Service Medal Silver Star (3) Distinguished Flying Cross Bronze Star Medal (5) Purple Heart (2) |

Jeremiah Andrew Denton Jr. (July 15, 1924 – March 28, 2014) was an American politician and military officer who served as a U.S. Senator representing Alabama from 1981 to 1987. He was the first Republican to be popularly elected to a Senate seat in Alabama. Denton was previously a United States Navy rear admiral and naval aviator taken captive during the Vietnam War.

Denton was widely known for enduring almost eight years of grueling conditions as an American prisoner of war (POW) in North Vietnam after the A-6 Intruder he was piloting suffered severe damage resulting from a defective bomb, which detonated as he released the weapon(s) in 1965. He was the first of the American POWs released by Hanoi to step off an American plane during Operation Homecoming on February 12, 1973. As one of the earliest and highest-ranking officers to be taken prisoner in North Vietnam, Denton was forced by his captors to participate in a 1966 televised propaganda interview which was broadcast in the United States. While answering questions and feigning trouble with the blinding television lights, Denton blinked his eyes in Morse code, spelling the word "T-O-R-T-U-R-E"—and confirming for the first time to U.S. Naval Intelligence that American POWs were being tortured.

In 1976, Denton wrote When Hell Was in Session about his experience in captivity, which was made into the 1979 film with Hal Holbrook. Denton was also the subject of the 2015 documentary Jeremiah produced by Alabama Public Television.

In 1980, Denton was elected to the U.S. Senate, where he focused mainly on family issues and national security, helping pass the Adolescent Family Life Act (the so-called "Chastity Bill") in 1981 and heading the Judiciary Subcommittee on Security and Terrorism.

In 2019, the United States Secretary of the Navy announced that an upcoming Arleigh Burke-class guided missile destroyer will be named in Denton's honor. Construction on USS Jeremiah Denton (DDG-129) began in August 2022.

Early life and education

Denton was born July 15, 1924, in Mobile, Alabama, the oldest of three brothers, and the son of Jeremiah Sr. and Irene (Steele) Denton.[1][2] He attended McGill–Toolen Catholic High School (Class of 1942) and Spring Hill College in Mobile, Alabama. His grandmother, Irene Claudia Jackson, was the grand-daughter of Roxana Virginia Hollinger, the daughter of Alexander Hollinger. Alexander Hollinger was the brother-in-law of Congressman George Washington Owen, the first member of Congress elected from Mobile in a district containing Mobile. Alexander Hollinger was the brother of Owen's wife Sarah Louise Hollinger.

In June 1943, he entered the United States Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland, and graduated three years later in the accelerated Class of 1947 on June 5, 1946, with a Bachelor of Science degree, the same class as future president Jimmy Carter.[3]

Career

.jpg.webp)

His 34-year naval career included service on a variety of ships and on aircraft, including airships. His principal field of endeavor was naval operations. He also served as a test pilot, flight instructor, and commanding officer of an attack squadron flying the A-6 Intruder.

In 1957, he was credited with revolutionizing naval strategy and tactics for nuclear war as architect of the "Haystack Concept." This strategy called for concealing aircraft carriers from radar by intermingling with commercial shipping and avoiding formations suggestive of a naval fleet. The strategy was simulated in maneuvers and demonstrated effectiveness, allowing two aircraft carrier fleets thirty-five simulated atomic launches before aggressor aircraft and submarines could repel them.[4] He went on to serve on the staff of the Commander, U.S. Sixth Fleet at the rank of Commander (O-5) as Fleet Air Defense Officer.

Denton graduated from the Armed Forces Staff College and the Naval War College, where his thesis on international affairs received top honors by earning the prestigious President's Award. In 1964, he received the degree of Master of Arts in international affairs from George Washington University's School of Public and International Affairs in Washington, D.C.

Vietnam War

Denton served as a United States Naval Aviator during the Vietnam War. In February 1965, he became the Prospective Commanding Officer of Attack Squadron Seventy-Five serving aboard aircraft carrier USS Independence (CV-62).

On July 18, 1965, Commander Denton was piloting his A-6A Intruder jet (BUNO 151577) while leading a 28-aircraft bombing mission over North Vietnam off the Independence which was stationed in the South China Sea. He and LTJG Bill Tschudy, his bombardier/navigator, were forced to eject from their plane, damaged by one of their own Mark 82 bombs exploding shortly after its release after which it went down out of control near the city of Thanh Hoa in North Vietnam. Both men were quickly captured and taken prisoner.[5]

Denton and Tschudy were held as prisoners of war for almost eight years, four of which were spent in solitary confinement. Denton was notable for his leadership during the Hanoi March in July 1966, when he and over 50 American prisoners were paraded through the streets of Hanoi and beaten by North Vietnamese civilians.[6] Denton is best known from this period of his life for the 1966 televised press conference in which he was forced to participate as an American POW by his North Vietnamese captors. He used the opportunity to send a distress message confirming for the first time to the U.S. Office of Naval Intelligence and Americans that American POWs were being tortured in North Vietnam. He repeatedly blinked his eyes in Morse code during the interview, spelling out the word "T-O-R-T-U-R-E". He was also questioned about his support for the U.S. war effort in Vietnam, to which he replied: "I don't know what is happening, but whatever the position of my government is, I support it fully. Whatever the position of my government, I believe in it, yes, sir. I am a member of that government, and it is my job to support it, and I will as long as I live."[7] While a prisoner, he was promoted to the rank of captain. Denton was later awarded the Navy Cross for heroism and the Purple Heart for wounds incurred while a prisoner of war.[8]

Denton was first sent to the Hỏa Lò Prison, nicknamed the "Hanoi Hilton", and was later transferred to the Cu Loc Detention Center, nicknamed the "Zoo". In 1967 he was transferred to a prison nicknamed "Alcatraz". Here, he became part of a group of American POWs known as the "Alcatraz Gang". The group consisted of George Coker, Harry Jenkins, Sam Johnson, George McKnight, James Mulligan, Howard Rutledge, Robert Shumaker, James Stockdale (who had graduated with Denton from the Naval Academy), Ronald Storz, and Nels Tanner. They were put in "Alcatraz" and solitary confinement to separate them from other POWs because their strong resistance led other POWs in resisting their captors. "Alcatraz" was a special facility in a courtyard behind the North Vietnamese Ministry of National Defense, located about one mile away from Hoa Lo Prison. Each of the American POWs spent day and night in windowless 3-by-9-foot (0.91 m × 2.74 m) cells mostly in legcuffs.[9][10][11][12][13]

On February 12, 1973, both Denton and Tschudy were released in Hanoi by the North Vietnamese along with numerous other American POWs during Operation Homecoming. Stepping off the jet back home in uniform, Denton said: "We are honored to have had the opportunity to serve our country under difficult circumstances. We are profoundly grateful to our Commander-in-Chief and to our nation for this day. God bless America." The speech has a prominent place in the 1987 documentary, Dear America: Letters Home from Vietnam.

Denton was briefly hospitalized at the Naval Hospital Portsmouth, Virginia, and then was assigned to the Commander, Naval Air Forces, U.S. Atlantic Fleet, from February to December 1973. In January 1974, Denton became the commandant of the Armed Forces Staff College in Norfolk (now known as the Joint Forces Staff College),[14][15] to June 1977.[16] His final assignment was as special assistant to the Chief of Naval Education and Training at Naval Air Station Pensacola, Florida, from June 1977 until his retirement from the Navy on November 1, 1977 with the rank of Rear Admiral.

After retirement

Denton accepted a position with the Christian Broadcasting Network (CBN) as a consultant to CBN founder and friend, Pat Robertson, from 1978 to 1980. During his time with CBN, both Denton and Robertson repeatedly expressed support for the Contra forces in Nicaragua. In 1981, he founded and chaired the National Forum Foundation. Through his National Forum Foundation, Denton arranged shipments of donated goods to countries in need of aid.[17]

Denton founded the Coalition for Decency, which tried to clean up television by urging boycotts of sponsors that promoted sexual promiscuity.[3]

Political career

In 1980, Denton ran as a Republican for a U.S. Senate seat from his home state of Alabama, and was supported by Jerry Falwell's Moral Majority.[3] In the primary election, he easily defeated former U.S. Congressman Armistead Selden, a Democrat who had switched parties and garnered the support of the Republican establishment in the state. He then achieved a surprise victory with 50.2 percent of the vote in November over Democratic candidate Jim Folsom Jr., who himself had defeated the incumbent, Donald W. Stewart, in the Democratic primary election. In doing so, Denton became the first retired Navy admiral elected to the United States Senate. He was the second retired Navy admiral to serve in the U.S. Senate, as Admiral Thomas C. Hart of Connecticut was appointed to fill a vacant Senate seat and served from November 15, 1945, to November 5, 1946.

He was the first Republican to be popularly elected in Alabama since the direct election of U.S. senators began in 1913, the first Republican senator since Reconstruction to represent Alabama in the U.S. Senate, and the first Catholic to be elected to statewide office in Alabama.

As a senator, Denton was most outspoken on issues related to the regulation of sexual promiscuity and the preservation of the nuclear family, a goal that he sought to pursue through a $30 million bill to push chastity among teenagers.[18] In 1981 he was able to pass the Adolescent Family Life Act (nicknamed the "Chastity Bill") as a part of the 1981 omnibus.

Denton was also outspoken on national security issues, particularly with regard to the Soviet Union. By the mid-1980s, he told Time at the outset of the decade, "We will have less national security than we had proportionately when George Washington's troops were walking around barefoot at Valley Forge."[18] Along with Republican senators Orrin Hatch and John East, Denton set up and later chaired the Senate Judiciary Subcommittee on Security and Terrorism, which focused on communist and Soviet threats.[19] Citing testimonies from journalist Claire Sterling, former CIA director William Colby, neoconservative writer Michael Ledeen and journalist and spy thriller writer Arnaud de Borchgrave, the committee alleged that left-wing activist groups, publications, and think tanks had been infiltrated by Soviet agents of the KGB.[20] Media at the time referred to committee's role and its accusations bearing similarity to the Red Scare tactics used by Senator Joseph McCarthy in the 1940s and 1950s.[21]

In 1986, Denton narrowly lost his bid for reelection to the U.S. Senate, receiving 49.7 percent of the vote against U.S. Congressman Richard Shelby, a conservative Democrat who later became a Republican.

Personal life

In 2007, Denton's first wife and the mother of his seven children, the former Kathryn Jane Maury, died after 61 years of marriage. He married Mary Belle Bordone in 2010.[22]

His children included James S. Denton, publisher and editor of World Affairs and the director of the World Affairs Institute.[23]

Denton died of complications from a heart ailment at a hospice in Virginia Beach on March 28, 2014, at age 89.[18] He is buried at Arlington National Cemetery with his wife Jane.[24][25]

Military awards

Denton's awards and decorations include:[26]

| ||

| Naval Aviator Badge | ||

| Navy Cross | Defense Distinguished Service Medal | Navy Distinguished Service Medal |

| Silver Star w/ two 5⁄16" Gold Stars |

Distinguished Flying Cross | Bronze Star w/ Combat "V" four 5⁄16" Gold Stars |

| Purple Heart w/ one 5⁄16" Gold Star |

Air Medal w/ Strike/Flight Numeral 2 |

Navy and Marine Corps Commendation Medal w/ Combat "V" |

| Combat Action Ribbon | Navy Unit Commendation | Prisoner of War Medal |

| Navy Expeditionary Medal | American Campaign Medal | World War II Victory Medal |

| Navy Occupation Service Medal w/ 'Japan' clasp |

National Defense Service Medal w/ one 3⁄16" Bronze Star |

Armed Forces Expeditionary Medal |

| Vietnam Service Medal w/ three 3⁄16" silver stars and one 3⁄16" bronze star |

Republic of Vietnam Gallantry Cross Unit Citation w/ Palm and Frame |

Vietnam Campaign Medal |

Navy Cross citation

- Denton Jr., Jeremiah Andrew

- Rear Admiral (then Commander), U.S Navy

- Prisoner of War in North Vietnam

- Date of Action: February 1966 – May 1966

- Citation:

- The President of the United States of America takes pleasure in presenting the Navy Cross to Rear Admiral [then Commander] Jeremiah Andrew Denton Jr. (NSN: 0-485087), United States Navy, for extraordinary heroism while serving as a Prisoner of War in North Vietnam from February 1966 to May 1966. Under constant pressure from North Vietnamese interrogators and guards, Rear Admiral Denton experienced harassment, intimidation and ruthless treatment in their attempt to gain military information and cooperative participation for propaganda purposes. During this prolonged period of physical and mental agony, he heroically resisted cruelties and continued to promulgate resistance policy and detailed instructions. Forced to attend a press conference with a Japanese correspondent, he blinked out a distress message in Morse Code at the television camera and was understood by United States Naval Intelligence. When this courageous act was reported to the North Vietnamese, he was again subjected to severe brutalities. Displaying extraordinary skill, fearless dedication to duty, and resourcefulness, he reflected great credit upon himself, and upheld the highest traditions of the Naval Service and the United States Armed Forces.[27]

Book

- Denton, Jeremiah (with Ed Brandt) (1976). When Hell Was in Session. Reader's Digest Press. ISBN 0-88349-112-5.

See also

References

- ↑ "United States Census, 1940," index and images, FamilySearch : accessed 28 Mar 2014, Irene S Denton, Ward 8, Mobile, Mobile City, Mobile, Alabama, United States; citing enumeration district (ED) 49-98A, sheet 8B, family 161, NARA digital publication of T627, roll 65.

- ↑ "Alabama, County Marriages, 1809–1950," index and images, FamilySearch : accessed 28 Mar 2014, Jeremiah Andrew Denton and Irene Claudia Steele, 22 Aug 1922; citing Mobile County; FHL microfilm 1550499.

- 1 2 3 "An Admiral from Alabama – Time". content.time.com. Retrieved 2019-04-20.

- ↑ Angevine, Robert (Spring 2011). "Hiding in Plain Sight: The US Navy and Dispersed Operations Under EMCON 1956–1972". Naval War College Review. 64 (2): 80–82. Archived from the original on 18 November 2011. Retrieved 9 January 2012.

- ↑ "POW Soldier Who Blinked "TORTURE" in Morse Code on TV". YouTube.

- ↑ Stuart I. Rochester and Frederick Kiley, Honor Bound: American Prisoners of War in Southeast Asia 1961–1973 (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1998)

- ↑ "Eyewitness". Archives.gov. Archived from the original on 2012-11-26. Retrieved 2012-11-19.

- ↑ Chawkins, Steve (March 29, 2014). "POW who blinked 'torture' in Morse code". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved June 29, 2023.

- ↑ Adams, Lorraine. "Perot's Interim Partner Spent 7½ Years As Pow", Dallas Morning News, March 11, 1992. Accessed July 2, 2008. "He was one of the Alcatraz Gang – a group of eleven prisoners of war who were separated because they were leaders of the prisoners' resistance."

- ↑ Rochester, Stuart; and Kiley, Frederick. "Honor Bound: American Prisoners of War in Southeast Asia, 1961–1973", 2007, Naval Institute Press, ISBN 1-59114-738-7, via Google Books, p. 326. Accessed July 8, 2008.

- ↑ Stockdale, James B. "George Coker for Beach Schools", letter to The Virginian-Pilot, March 26, 1996.

- ↑ Johnston, Laurie (December 18, 1974). "Notes on People, Mao Meets Mobutu in China h". The New York Times. Retrieved May 3, 2010. Dec 18, 1974

- ↑ Kimberlin, Joanne (2008-11-11). "Our POW's: Locked up for 6 years, he unlocked a spirit inside". The Virginian Pilot. Landmark Communications. pp. 12–13. Archived from the original on 2014-11-25. Retrieved 2008-11-11.

- ↑ "Denton unhappy, may leave Navy". Free Lance-Star. Fredericksburg, Virginia. Associated Press. May 15, 1975. p. 5.

- ↑ Riley, Dave (May 17, 1975). "Admiral wants to improve morality". Free Lance-Star. Fredericksburg, Virginia. Associated Press. p. 4.

- ↑ Jones, Matthew (2008-08-13). "Ex-Vietnam War POW a man committed to cooperation | HamptonRoads.com | PilotOnline.com". HamptonRoads.com. Archived from the original on 2014-08-17. Retrieved 2012-11-19.

- ↑ "Ex-senator and Vietnam POW who blinked "torture" in Morse code dies". CBS News. 28 March 2014. Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- 1 2 3 "Jeremiah A. Denton Jr., Vietnam POW and U.S. senator, dies". The Washington Post. March 28, 2014. Retrieved March 28, 2014.

- ↑ "Statement by Senator Jeremiah Denton before the subcommittee on security and terrorism February 2, 1983". Terrorism. 7 (1): 73–80. January 1984. doi:10.1080/10576108408435562. ISSN 0149-0389.

- ↑ Mohr, Charles; Times, Special to The New York (1981-04-25). "Hearing on Terror Opens with Warning on Soviet". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2019-04-20.

- ↑ Lardner Jr., George (April 20, 1981). "Assault on Terrorism: Internal Security or Witch Hunt?". The Washington Post. Retrieved April 20, 2019.

- ↑ https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/BILLS-113sres407ats/html/BILLS-113sres407ats.htm

- ↑ Schudel, Matt (23 June 2018). "James S. Denton, journal editor who led programs to advance democracy, dies at 66". Washington Post. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

- ↑ "Burial Detail: Denton, Jeremiah Andrew". ANC Explorer. Retrieved December 13, 2020.

- ↑ "Jeremiah Denton Jr". Encyclopedia of Alabama. Retrieved July 28, 2018.

- ↑ "Veteran Tributes". Veteran Tributes. Retrieved 2017-11-15.

- ↑ Jeremiah Andrew Denton Jr. "Valor awards for Jeremiah Andrew Denton, Jr". Valor.militarytimes.com. Retrieved 2017-11-15.

External links

- Biography of Senator Denton in the Biographical Directory of the US Congress

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- Admiral Jeremiah Denton Foundation

- Jeremiah Denton Jr. at the Encyclopedia of Alabama

- Article on RADM Denton not being allowed to speak before California Assembly on July 4, 2004