Jonah of Moscow | |

|---|---|

| Metropolitan of Kiev and All Rus | |

| |

| Church | Russian Orthodox Church |

| See | Moscow |

| Installed | 1448 |

| Term ended | 1461 |

| Predecessor | Isidore of Kiev |

| Successor | Theodosius, Metropolitan of Moscow |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1390s |

| Died | 31 March 1461 |

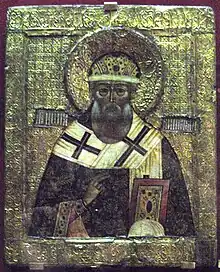

Jonah of Moscow (Иона in Russian) (died 1461), was the Metropolitan of Kiev and all Rus'. He reigned from 1448 to his death in 1461. He was appointed at the behest of the secular authorities in Muscovy as his predecessor on the throne — Isidore of Kiev — was adjudged to have apostatized to Catholicism.[1] Like his immediate predecessors, he permanently resided in Moscow, and was the last Moscow-based primate of the metropolis to keep the traditional title with reference to the metropolitan city of Kiev. He was also the first metropolitan in Moscow to be appointed without the approval of the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople as had been the norm.[2] He is recognised as a saint in the Russian Orthodox Church.

Career

Since the late 1420s, Jonah had been living in the Simonov Monastery in Moscow and was close to Metropolitan Photius, who make him Bishop of Ryazan and Murom. After Photius's death in 1431, Grand Prince Vasili II nominated Jonas for the post of Metropolitan, but the Uniate Patriarch Joseph II chose Isidore to become the Metropolitan of Kiev and All Rus'.

After the death of Photios in 1431, Jonah was chosen by the grand prince and the council of bishops as the new Metropolitan of Kiev and all Rus' at the end of 1432. However, due to internal strifes in Muscovy, he did not hurry to Constantinople to receive his ordination and did not decide to go to Constantinople until the middle of 1435. Meanwhile, at the request of the Lithuanian Grand Duke Švitrigaila, bishop Gerasim of Smolensk was appointed Metropolitan of Kiev and all Rus', but the latter did not come to Moscow and remained Metropolitan only in Lithuania. Soon, Švitrigaila suspected Gerasim of treason and executed him in 1435.[3][4]

When Jonah finally arrived to Constantinople in 1436, the Ecumenical Patriarch had already chosen the Greek bishop Isidore and appointed the latter as the new Metropolitan of Kiev and All Rus'. Isidore came to Moscow in 1437 and made a good impression there with his diplomatic skills and knowledge of the Slavonic language. However, only 5 months later, in September 1437, he left Moscow to participate to the Council of Florence, where the unification of the Churches of Rome and Constantinople should be adopted.[5]

After Isidore had been condemned and deposed by Vasily II and his bishops in Moscow in 1441, for his attempts to implement the decision on the Union of the Eastern and Western (Roman) Churches agreed upon at the Council of Florence-Ferrara, the metropolitan throne sat vacant for seven years.

Schism

Jonah was elected by a majority of bishops in the Muscovy part of the metropolis on 15 December 1448, without the consent of the Patriarch of Constantinople.[6] While it is possible that the failure to obtain the blessing from Constantinople was not intentional, nevertheless, this signified the beginning of the de facto independence (autocephaly) of the north-eastern part of the Church in Russia.

Jonah fought a losing battle to prevent the loss of his south-western suffragans: in 1458, the uniate Patriarch Gregory III of Constantinople appointed Gregory the Bulgarian as metropolitan of the newly established Metropolis of Kiev, Galich and all Rus'. The Polish-Lithuanian rulers of those lands supported Gregory.[7]

Jonah died on March 31, 1461. He was buried in the Cathedral of the Dormition in the Moscow Kremlin. He was canonized by Macarius, Metropolitan of Moscow at the Moscow Council of 1547.[8]

References

- ↑ ИОНА // Orthodox Encyclopedia

- ↑ E. E. Golubinskii, Istoriia russkoi tserkvi (Moscow: Universitetskaia tipografiia, 1900), vol. 2, pt. 1, p. 469.

- ↑ Shubin, Daniel (2004). A History of Russian Christianity. Volume I: From the Earliest Years through Tsar Ivan IV. New York: Algora Publishing. pp. 124–125. ISBN 978-0-87586-289-7.

- ↑ Zheltov, Mikhail, Historical-Canonical Basis for the Unity of the Russian Church (in Russian: Историко-канонические основания единства Русской Церкви) (also in Russian on Academia.edu)

- ↑ Shubin 2004, pp. 125–126.

- ↑ Golubinskii, Istoriia russkoi tserkvi, vol. 2, pt. 1, pp. 479-480, 484.

- ↑ Golubinskii, Istoriia russkoi tserkvi vol. 2, pt. 1, pp. 491-2.

- ↑ Golubinskii, Istoriia russkoi tserkvi, vol. 2, pt. 1, p. 515.