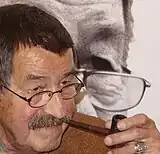

Front cover of the first original German edition | |

| Author | Günter Grass |

|---|---|

| Original title | Katz und Maus |

| Illustrator | Günter Grass |

| Cover artist | Günter Grass |

| Country | Germany |

| Language | German |

| Series | Danzig Trilogy |

| Genre | Novel |

| Publisher | Luchterhand |

Publication date | 1961 |

| Media type | Print (Hardback & Paperback) |

| Preceded by | The Tin Drum |

| Followed by | Dog Years |

Cat and Mouse (German: Katz und Maus) is a 1961 novella by German writer Günter Grass, the second book of the Danzig Trilogy, and the sequel to The Tin Drum. It is about Joachim Mahlke, an alienated only child without a father. The narrator Pilenz "alone could be termed his friend, if it were possible to be friends with Mahlke" (p. 78); much of Pilenz's narration addresses Mahlke directly by means of second-person narration. The story is set in Danzig (Gdańsk) around the time of the Second World War and Nazi rule.

Plot summary

The narrator describes the character "The Great Mahlke" from their youth together through to Mahlke's disappearance near the end of the Second World War. Much of the action of the story is on a half-submerged sunken minesweeper of the Polish Navy, on which the narrator, Mahlke and their friends meet each summer. Mahlke explores the shipwreck by diving through a hatch, and with his ever-present screwdriver salvages various items (information plaques, objects left behind by the crew, and even a gramophone) to sell or collect for himself.

Over the course of the novella Mahlke steals a Knight's Cross from a visiting U-boat captain and is expelled from school. He joins a Panzer division and receives a Knight's Cross thanks to his successes in battle. Returning to the school from which he was expelled, however, the principal forbids him from making a speech to the students, on the grounds of his former disgrace.

The narrative in the story is often fairly incoherent. For instance, the timeline of the narration is often treated flexibly, moving from the narrator's perspective to different points within his memory of the events. There is also disunity about whether Mahlke is addressed in the second- or third-person, with Grass sometimes changing the form of address within a single sentence, possibly indicating the narrator's inability to remove his own emotions and feelings of guilt from an objective account of Mahlke.

Mahlke, with the help of the narrator, returns to the shipwreck. Mahlke's main reason for entering the war in the first place was to make a speech at his school afterwards. Since he is denied that wish, Mahlke deserts his post, seeing no other reason to fight. Desertion implies treason and in consequence death. Pilenz, whose relationship to Mahlke becomes increasingly ambivalent, takes advantage of the situation and pressures an unwell Mahlke to dive into the wreck once more to hide, aware that Mahlke might not survive the dive. Pilenz never sees Mahlke again.

Interpretations

The title relates to the central metaphor, in which Mahlke is the mouse and society is the cat. Mahlke's large larynx is the leitmotif:

...Mahlke's Adam's apple had become the cat's mouse. It was so young a cat, and Mahlke's whatsis was so active — in any case the cat leapt at Mahlke's throat; or one of us caught the cat and held it up to Mahlke's neck; or I ... seized the cat and showed it Mahlke's mouse; and Joachim Mahlke let out a yell, but suffered only slight scratches. (p. 6)

The anthropomorphism and metaphorical embodiment of gross social forces is common in Grass's work; here the sentence "It was a young cat, but no kitten" describes the German state in the 1940s — young but by no means innocent (p. 5). The narrative style — the evasion, self-justification, and eventual, chatty disclosure of the truth — is also characteristic.

References

The quoted English edition is:

- Grass, Günter (1975) [1961]. Ralph Manheim (translator) (ed.). Cat and Mouse. Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-002542-1.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help)