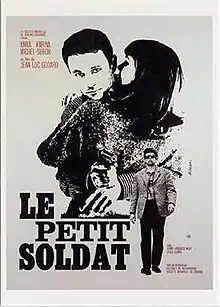

| Le petit soldat | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Jean-Luc Godard |

| Written by | Jean-Luc Godard |

| Produced by | Georges de Beauregard |

| Starring | Michel Subor Anna Karina |

| Cinematography | Raoul Coutard |

| Edited by | Agnès Guillemot Lila Herman Nadine Marquand |

| Music by | Maurice Leroux |

Release date | 1963 |

Running time | 88 minutes |

| Country | France |

| Language | French |

Le petit soldat (transl. The Little Soldier) is a French film written and directed by Jean-Luc Godard in 1960, but not released until 1963. It was the first project on which Godard worked with Anna Karina, who stars alongside Michel Subor, but the third to be released.

Plot

In 1958, during the Algerian War, Bruno Forestier is a deserter from the French army living in Geneva. Although he does not have particularly strong political convictions, he finds himself working for La Main Rouge, a French terrorist organization, while posing as a reporter. To prove he is not a double agent, he is ordered to kill Arthur Palivoda, a radio host who is pro-FLN (National Liberation Front) and in favor of Algerian independence. Although he has killed before, Bruno refuses this time, initially saying it is too dangerous, and then that he does not feel like doing it.

Bruno meets and falls in love with Véronica Dreyer, who, unbeknownst to him, is working with the FLN. When his compatriots in La Main Rouge stage a hit-and-run with his car, Bruno agrees to carry out the assassination so the charges will be dropped and he will not be sent back to France, but he keeps hesitating and then decides again not to kill Palivoda.

Now viewed as a traitor by the French, Bruno plans to escape to Brazil with Véronica, but he is captured and tortured by the Algerians, who had seen him following Palivoda. Eventually, he manages to escape by jumping through the window of the room in which he is being held, which turns out to be on the second floor. He tries to get two diplomatic passports from the French by telling them where he was held, but the Algerians have moved out, so he agrees to finally kill Palivoda to get the papers. Having discovered Véronica's ties to the FLN, the French abduct her, which they tell Bruno to try to gain additional leverage over him, and torture her for the location of the Algerians' current hideout. After Bruno kills Palivoda, he learns Véronica has died, but he says he learned not to be bitter about it.

Cast

- Michel Subor as Bruno Forestier

- Anna Karina as Veronica Dreyer

- Henri-Jacques Huet as Jacques

- Paul Beauvais as Paul

- László Szabó as Laszlo

Production and release

The film was the first project on which Godard worked with Anna Karina. They were married in 1961, and she would go on to star in six more of his films, as well as his segment of the anthology film The Oldest Profession (1967).

Due to its inclusion of torture scenes and other controversial political content, the film was banned in France until January 1963, which was after the end of the Algerian War. Thus, while it was the second feature film directed by Godard (the first being 1960's À bout de souffle), it was the fourth to be released.

Reception

Le petit soldat has received generally positive reviews since its release. On review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, it has an approval rating of 80% based on 20 reviews, with an average score of 7/10.[1] In a retrospective review, Roger Ebert awarded the film four stars out of four.[2]

Themes

The situation in Algeria and the denunciation of the use of torture by both sides are the main themes of the film. Additionally, it explores a theme typical of Jean-Luc Godard's later works: the nature of cinema and the image.

References

- ↑ "Le petit soldat (1963) on RT". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved March 16, 2023.

- ↑ "Le Petit Soldat movie review & film summary (1960) | Roger Ebert".

External links

- Le Petit Soldat at IMDb

- Le petit soldat at AllMovie

- Le petit soldat at the TCM Movie Database

- Review of DVD of Le Petit Soldat

- Roger Ebert review of Le Petit Soldat Archived 2012-09-26 at the Wayback Machine

- Le petit soldat: The Awful Truth an essay by Nicholas Elliott at The Criterion Collection