Leaky-wave antenna (LWA) belong to the more general class of traveling wave antenna, that use a traveling wave on a guiding structure as the main radiating mechanism. Traveling-wave antenna fall into two general categories, slow-wave antennas and fast-wave antennas, which are usually referred to as leaky-wave antennas.

Introduction

The traveling wave on a Leaky-Wave Antenna is a fast wave, with a phase velocity greater than the speed of light. This type of wave radiates continuously along its length, and hence the propagation wavenumber kz is complex, consisting of both a phase and an attenuation constant. Highly directive beams at an arbitrary specified angle can be achieved with this type of antenna, with a low sidelobe level. The phase constant β of the wave controls the beam angle (and this can be varied changing the frequency), while the attenuation constant α controls the beamwidth. The aperture distribution can also be easily tapered to control the sidelobe level or beam shape. Leaky-wave antennas can be divided into two important categories, uniform and periodic, depending on the type of guiding structure.

Uniform LWA

A uniform structure has a cross section that is uniform (constant) along the length of the structure, usually in the form of a waveguide that has been partially opened to allow radiation to occur. The guided wave on the uniform structure is a fast wave, and thus radiates as it propagates.

Periodic LWA

A periodic leaky wave antenna structure is one that consists of a uniform structure that supports a slow (non radiating) wave that has been periodically modulated in some fashion. Since a slow wave radiates at discontinuities, the periodic modulations (discontinuities) cause the wave to radiate continuously along the length of the structure. From a more sophisticated point of view, the periodic modulation creates a guided wave that consists of an infinite number of space harmonics (Floquet modes). Although the main (n = 0) space harmonic is a slow wave, one of the space harmonics (usually the n = −1) is designed to be a fast wave, and this harmonic wave is the radiating wave.

Slotted guide

A typical example of a uniform leaky-wave antenna is an air-filled rectangular waveguide with a longitudinal slot. This simple structure illustrates the basic properties common to all uniform leaky-wave antennas. The fundamental TE10 waveguide mode is a fast wave, with , where k0 is the vacuum wavenumber. The radiation causes the wavenumber kz of the propagating mode within the open waveguide structure to become complex. By means of an application of the stationary-phase principle, it can be found in fact that:

where θm is the angle of maximum radiation taken from broadside (x direction), and λ0 are the light velocity and the wavelength in vacuum, and λg is the guide wavelength. As is typical for a uniform LWA, the beam cannot be scanned too close to broadside (θm=0), since this corresponds to the cutoff frequency of the waveguide. In addition, the beam cannot be scanned too close to endfire (θm=90°,z direction) since this requires operation at frequencies significantly above cutoff, where higherorder modes can propagate, at least for an air-filled waveguide. Scanning is limited to the forward quadrant only (0<θm<Π/2), for a wave traveling in the positive z direction.

This one-dimensional (1D) leaky-wave aperture distribution results in a "fanbeam" having a narrow shape in the xz plane (H plane), and a broad shape in the cross-plane. A "pencil beam" can be created by using an array of such 1D radiators. Unlike the slow-wave structure, a very narrow beam can be created at any angle by choosing a sufficiently small value of α. A simple formula for the beam width, measured between half-power points (), is:

where L is the length of the leaky-wave antenna, and Δθ is expressed in radians. For 90% of the power radiated it can be assumed:

Since leakage occurs over the length of the slit in the waveguiding structure, the whole length constitutes the antenna's effective aperture unless the leakage rate is so great that the power has effectively leaked away before reaching the end of the slit. A large attenuation constant implies a short effective aperture, so that the radiated beam has a large beamwidth. Conversely, a low value of α results in a long effective aperture and a narrow beam, provided the physical aperture is sufficiently long. Since power is radiated continuously along the length, the aperture field of a leaky-wave antenna with strictly-uniform geometry has an exponential decay (usually slow), so that the sidelobe behavior is poor. The presence of the sidelobes is essentially because the structure is finite along z. When we change the cross-sectional geometry of the guiding structure to modify the value of α at some point z, however, it is likely that the value of β at that point is also modified slightly. However, since β must not be changed, the geometry must be further altered to restore the value of β, thereby changing α somewhat as well.

In practice, this difficulty may require a two-step process. The practice is then to vary the value of α slowly along the length in a specified way while maintaining β constant (that is the angle of maximum radiation), so as to adjust the amplitude of the aperture distribution A(z) to yield the desired sidelobe performance. We can divide uniform leaky-wave antennas into air-filled ones and partially dielectric-filled ones. In the first case, since the transverse wavenumber kt is then a constant with frequency, the beamwidth of the radiation remains exactly constant as the beam is scanned by varying the frequency. In fact, since:

where:

independent of frequency (λc is the cutoff wavelength). On the contrary, when the guiding structure is partly filled with dielectric, the transverse wavenumber kt is a function of frequency, so that Δθ changes as the beam is frequency scanned. On the other hand, with respect to frequency sensitivity, i.e., how quickly the beam angle scans as the frequency is varied, the partly dielectric-loaded structure can scan over a larger range of angles for the same frequency variation, as it is apparent in Fig. 2, and is therefore preferred.

Non-radiative dielectric waveguide (NRD)

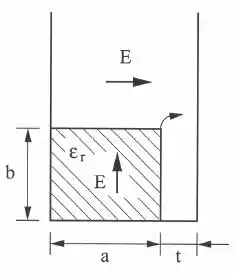

In response to requirements at millimeter wavelengths, the new antennas were generally based on lower-loss open waveguides. One possible mechanism to obtain radiation is foreshortening a side. Consider for example the Non-Radiative Dielectric waveguide (NRD).

The spacing a between the metal plates is less than λ0/2 so that all junctions and discontinuities (also curves) that maintain symmetry become purely reactive, instead of possessing radiative content. When the vertical metal plates in the NRD guide are sufficiently long, the dominant-mode field is completely bound, since it has decayed to negligible values as it reaches the upper and lower open ends. If the upper portion of the plates is foreshortened, as in Fig. 3, a traveling-wave field of finite amplitude then exists at the upper open end, and if the dominant NRD guide mode is fast (it can be fast or slow depending on the frequency), power will be radiated away at an angle from this open end.

Another possible mechanism is asymmetry. In the asymmetrical NRD-guide antenna depicted in Fig. 4, the structure is first bisected horizontally with a metallic wall, to provide radiation from one end only; since the electric field is purely vertical at this midplane, the field structure in not altered by the bisection. An air gap is then introduced into the dielectric region to produce asymmetry. As a result, a small amount of net horizontal electric field is created, which produces a mode in the parallel-plate air region, which is a TEM mode, which propagates at an angle between the parallel plates until it reaches the open end and leaks away. It is necessary to maintain the parallel plates in the air region sufficiently long so that the vertical electric-field component of the original mode (represented in the parallel-plate guide by the below-cutoff TM1 mode) has decayed to negligible values at the open end. Then the TEM mode, with its horizontal electric field, is the only field left at the antenna aperture, and the field polarization is then essentially pure (the discontinuity at the open end does not introduce any cross-polarized field components).

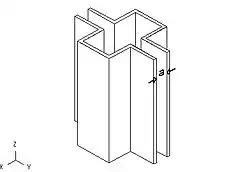

Groove guide

Groove guide (shown in Fig. 5) is a low-loss open waveguide for millimeter waves, somewhat similar to the NRD guide: the dielectric central region is replaced by an air region of larger width (greater than λ0/2). The field again decays exponentially in the regions of narrower width above and below. The leaky-wave antenna is created by first bisecting the groove guide horizontally. It also resembles a stub-loaded rectangular waveguide.

When the stub is off-centered, the asymmetrical structure obtained will radiate. When the offset is increased, the attenuation constant α will increase and the beamwidth will increase too. When the stub is placed all the way to one end, the result is an L-shaped structure that radiates very strongly.

In addition, it is found that the value of β changes very little as the stub is moved, and α varies over a very large range. This feature allows to taper the antenna aperture to control sidelobes. The fact that the L-shaped structure strongly leaks may also be related to another leakage mechanism: the use of leaky higher modes. In particular, it may be found that all the groove-guide higher modes are leaky.

For example, consider the first higher antisymmetric mode. Because of the symmetry of the structure and the directions of the electric-field lines, the structure can be bisected twice to yield the L-shaped, as represented in Fig. 6.

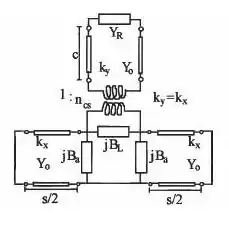

The antenna may be analyzed using a transverse equivalent network based on a T-junction network. The expressions for the network elements are obtainable in simple closed forms and yet are very accurate. The resulting circuit is shown in Fig. 7.

Usually, the stub length needs only to be about half a wavelength or less if the stub is narrow.

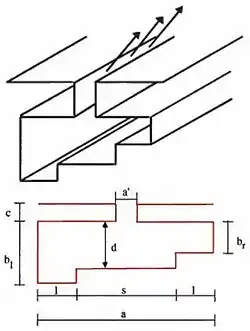

To exploit the possibility of printed-circuit techniques, a printed-circuit version of the previous structure has been developed. In this way the fabrication process could make use of photolithography, and the taper design for sidelobe control could be handled automatically in the fabrication.

The structure is depicted in the inset of Fig. 8. The transverse equivalent network for this new antenna structure is slightly more complicated than the previous, and the expressions for the network elements must be appropriately modified to take the dielectric medium into account. Moreover, above the transformer, an additional susceptance appears.

The stub and main guides are no longer the same, so their wavenumbers and characteristic admittances are also different. Again,α can be varied by changing the slot location d, as it is apparent in Fig.8. However, it was found that a' is also a good parameter to change for this purpose, as shown in Fig.9.

Stepped guide (ridge)

An interesting variation of the previous structures has been developed and analyzed. It is based on a ridge or stepped waveguide rather than a rectangular waveguide. In the structures based on rectangular waveguide, the asymmetry was achieved by placing the stub guide, or locating the longitudinal slot, off-center on the top surface.

Here the top surface is symmetrical, and the asymmetry is created by having unequal lengths on each side under the main-guide portion, as shown in Fig. 10. The transverse equivalent networks, together with the associated expressions for the network elements, were adapted and extended to apply to these new structures. The equivalent circuit is represented in Fig. 11. An analysis of the antenna behavior indicates that this geometry effectively permits independent control of the angle of maximum radiation θm and of the beamwidth Δθ. Let us define two geometric parameters: the relative average arm length bm/a where bm = (bl+br)/2, and the relative unbalance Δb/bm where Δb=(bl+br)/2 . Figure 10: Stepped guide. It then turns out that by changing bm/a one can adjust the value of β/k0 without altering α/k0 much, and that by changing Δb/bm one can vary α/k0 over a large range without affecting β/k0 much.

The taper design for controlling the sidelobe level would therefore involve only the relative unbalance Δb/bm. The transverse equivalent network is slightly complicated by the presence of two additional changes in height of the waveguide, which can be modeled by means of shunt susceptances and ideal transformers. The ideal transformer accounts for the change in the characteristic impedance, while the storing of reactive energy is taken into account through the susceptance. Scanning arrays achieve scanning in two dimensions by creating a one-dimensional phased array of leaky-wave line-source antennas. The individual line sources are scanned in elevation by varying the frequency. Scanning in the cross plane, and therefore in azimuth, is produced by phase shifters arranged in the feed structure of the one-dimensional array of line sources. The radiation will therefore occur in pencil-beam form and will scan in both elevation and azimuth in a conical-scan manner. The spacing between the line sources is chosen such that no grating lobes occur, and accurate analyses show that no blind spots appear anywhere. The described arrays have been analyzed accurately by unit-cell approach that takes into account all mutual-coupling effects. Each unit cell incorporates an individual line-source antenna, but in the presence of all the others. The radiating termination on the unit cell modifies the transverse equivalent network. A key new feature of the array analysis is therefore the determination of the active admittance of the unit cell in the two-dimensional environment as a function of scan angle. If the values of β and α did not change with phase shift, the scan would be exactly conical. However, it is found that these values change only a little, so that the deviation from conical scan is small. We next consider whether or not blind spots are present. Blind spots refer to angles at which the array cannot radiate or receive any power; if a blind spot occurred at some angle, therefore, the value of α would rapidly go to zero at that scan angle. To check for blind spots, we would then look for any sharp dips in the curves of α/k0 as a function of scan angle. No such dips were ever found. Typical data of this type exhibit fairly flat behavior for α/k0 until the curves drop quickly to zero as they reach the end of the conical-scan range, where the beam hits the ground.

References

- C. H. Walter, Traveling Wave Antennas, McGraw-Hill, 1965, Dover, 1970, reprinted by Peninsula Publishing, Los Altos, California, 1990.

- N. Marcuvitz, Waveguide Handbook, McGraw-Hill, 1951, reprinted by Peter Peregrinus Ltd, London, 1986.

- V. V. Shevchenko, Continuous transitions in open waveguides: introduction to the theory, Russian Edition, Moscow, 1969, The Golem Press, Boulder, Colorado 1971.

- T. Rozzi and M. Mongiardo, Open Electromagnetic Waveguides, The Institution of Electrical Engineers(IEE), London, 1997.

- M. J. Ablowitz and A. S. Fokas, Complex variables: Introduction and Applications, second edition, Cambridge University Press, 2003.

- A. A. Oliner (principal investigator), Scannable millimeter wave arrays, Final Report on RADC Contract No. F19628-84-K-0025, Polytechnic University, New York, 1988.

- A. A. Oliner, Radiating periodic structures: analysis in terms of k vs. β diagrams, short course on Microwave Field and Network Techniques, Polytechnic Institute of Brooklyn, New York, 1963.

- A. A. Oliner (principal investigator), Lumped-Element and Leaky-Wave Antennas for Millimeter Waves, Final Report on RADC Contract No. F19628-81-K-0044,Polytechnic Institute of New York, 1984.

- F. J. Zucker, "Surface and leaky-wave antennas," Chapter 16 of Antenna Engineering Handbook, H. J. Jasik, Editor, McGraw-Hill, New York, 1961.

- A. A. Oliner and T. Tamir, "Guided complex wave, part I: field at an interface," Proc. IEE, Vol. 110, pp. 310–324, February 1963.

- A. A. Oliner and T. Tamir, "Guided complex wave, part II: relation to radiation pattern," Proc. IEE, Vol. 110, pp. 325-334, February 1963.

- A. A. Oliner, \Leaky-Wave Antennas," Chapter 10 in Antenna Engineering Handbook, R. C. Johnson, Editor, 3rd ed., McGraw-Hill, New York, 1993, 59 pages.

- A. Hessel, "General characteristics of traveling-wave antennas," Chapter 19 in Antenna Theory, R. E. Collin and F. J. Zucker, Editors, McGraw-Hill, New York, 1969, pp. 151-257.

- F. J. Zucker, "Surface-Wave Antennas," Chapter 21 in Antenna Theory, R. E. Collin and F. J. Zucker, Editors, McGraw-Hill, New York, 1969, pp. 298–348.

- F. Schwering and S. T. Peng, Design of periodically corrugated dielectric antennas for millimeter-wave applications, Polytechnic Institute of Brooklyn, New York, 1983, 22 pages.

- S. T. Peng and A. A. Oliner, "Guidance and leakage properties of a class of open dielectric waveguides: Part I - Mathematical Formulations," IEEE Transactions on Microwave Theory and Techniques, Vol. MTT-29, September 1981, pp. 843- 855.

- A. A. Oliner, S. T. Peng, T. I. Hsu, and A. Sanchez,\Guidance and leakage properties of a class of open dielectric waveguides: Part II - New Physical Effects," IEEE Transactions on Microwave Theory and Techniques, Vol. MTT-29, September 1981, pp. 855–869.

- A. A. Oliner and R. G. Malech, "Mutual coupling in infinite scanning arrays," Chapter 3 in Microwave Scanning Antennas, Vol. II, R. C. Hansen, Editor, Academic, New York, 1966.

- F. Monticone, and A. Alù, “Leaky-Wave Theory, Techniques and Applications: From Microwaves to Visible Frequencies,” Proceedings of IEEE, Vol. 103, No. 5, pp. 793-821, May 26, 2015. doi: 10.1109/JPROC.2015.2399419

- M. Poveda-Garcia, J. Oliva-Sanchez, R. Sanchez-Iborra, D. Cañete-Rebenaque, J. L. Gomez-Tornero, "Dynamic Wireless Power Transfer for Cost-Effective Wireless Sensor Networks Using Frequency-Scanned Beaming". IEEE Access, 7, 8081–8094. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2018.2886448