| |

| Full name | Luzhniki Stadium |

|---|---|

| Former names | Central Lenin Stadium (1956–1992) |

| Public transit | |

| Owner | Government of Moscow |

| Operator | Luzhniki Olympic Sport Complex JSC |

| Capacity | 81,000 (60,000 with proposed extra platform for athletics)[1] |

| Record attendance | 102,538 (Soviet Union–Italy, 13 October 1963) |

| Field size | 105 by 68 metres (114.8 yd × 74.4 yd) |

| Surface | SISGrass (Hybrid Grass) |

| Construction | |

| Broke ground | 1955 |

| Opened | 31 July 1956 |

| Renovated |

|

| Construction cost | €350 million (2013–2017)[2] |

| Architect | PA Arena, Gmp Architekten and Mosproject-4 |

| Tenants | |

| Russia national football team (selected matches) FC Torpedo Moscow (since 2022) | |

| Website | |

| eng | |

Luzhniki Stadium (Russian: стадион «Лужники», IPA: [stədʲɪˈon lʊʐnʲɪˈkʲi], Stadion Luzhniki) is the national stadium of Russia, located in its capital city, Moscow. The full name of the stadium is Grand Sports Arena of the Luzhniki Olympic Complex. Its total seating capacity of 81,000 makes it the largest football stadium in Russia and the ninth-largest stadium in Europe. The stadium is a part of the Luzhniki Olympic Complex, and is located in Khamovniki District of the Central Administrative Okrug of Moscow city. The name Luzhniki derives from the flood meadows in the bend of Moskva River where the stadium was built, translating roughly as "The Meadows". The stadium is located at Luzhniki Street, 24, Moscow.

Luzhniki was the main stadium of the 1980 Olympic Games, hosting the opening and closing ceremonies, as well as some of the competitions, including the final of the football tournament. A UEFA Category 4 stadium, Luzhniki hosted the UEFA Cup final in 1999 and UEFA Champions League final in 2008. The stadium also hosted such events as Summer Universiade, Goodwill Games and World Athletics Championships. It was the main stadium of the 2018 FIFA World Cup and hosted 7 matches of the tournament, including the opening match and the final.

In the past, its field has been used as the home ground for many years of football rivals Spartak Moscow and CSKA Moscow. It is currently used for some matches of the Russia national football team, as well as being used for various other sporting events and for concerts. Luzhniki Stadium is currently the temporary home ground of FC Torpedo Moscow.

Location

The stadium is located in Khamovniki District[3] of the Central Administrative Okrug of Moscow city, south-west of the city center. The name Luzhniki derives from the flood meadows in the bend of Moskva River where the stadium was built, translating roughly as "The Meadows". It was necessary to find a very large plot of land, preferably in a green area close to the city center that could fit into the transport map of the capital without too much difficulty.[4]

According to one of the architects: "On a sunny spring day of 1954, we, a group of architects and engineers who were tasked with designing the Central stadium, climbed onto a large paved area on the Lenin Hills [which after the Soviet era would revert to their old name, the Sparrow Hills ]... the proximity of the river, green mass of clean, fresh air – this circumstance alone mattered to select the area of the future city of sports... In addition, Luzhniki is located relatively close to the city center and convenient access to major transport systems with all parts of the capital".[5]

Playing surface

It was one of the few major European football stadia to use an artificial pitch, having installed a FIFA-approved FieldTurf pitch in 2002. However, a temporary natural grass pitch was installed for the 2008 UEFA Champions League Final.[6] The game between Chelsea and Manchester United was the first UEFA Champions League final held in Russia.[7][8] On the match day, UEFA gave Luzhniki its elite status.[9]

In August 2016 a permanent hybrid turf was installed, consisting of 95 percent natural grass reinforced with plastic.[10]

History

Background and early years

On 23 December 1954, the Government of the USSR adopted a resolution on the construction of a stadium in the Luzhniki area in Moscow.[11] The decision of the Soviet Government was a response to a specific current international situation: By the early 1950s, Soviet athletes took to the world stage for the first time after World War II (rus. the Great Patriotic War), participating in the Olympic Games. The 1952 Summer Olympics in Helsinki brought the Soviet team 71 medals (of which 22 gold) and second place in the unofficial team standings.[12]

It was a success, but the increased athletic development of the Soviet Union, which was a matter of state policy, required the construction of a new sports complex. The proposed complex was to meet all modern international standards and at the same time serve as a training base for the Olympic team and arena for large domestic and international competitions.

The stadium was built in 1955–56 as the Grand Arena of the Central Lenin Stadium. The design began in January 1955 and was completed in 90 days[13] by the architects Alexander Vlasov, Igor Rozhin, Nikolai Ullas, Alexander Khryakov and engineers Vsevolod Nasonov, Nikolai Reznikov, Vasily Polikarpov.[14] Building materials came from Leningrad and the Armenian SSR, electrical and oak beams for the spectator benches from the Ukrainian SSR, furniture from Riga and Kaunas, glass was brought from Minsk, electrical equipment from Podolsk in Moscow Oblast, and larch lumber from Irkutsk in Siberia. It was necessary to demolish a whole area of dilapidated buildings (including the Trinity Church, which is supposed to be restored). Because the soil was heavily waterlogged, almost the entire area of the foundations of the complex had to be raised half a meter. 10,000 piles were hammered into the ground and dredgers reclaimed about 3 million cubic metres of soil. The total area of the stadium occupies 160 hectares.[15] Eight thousand people moved home to make place for the stadium. The Church Tikhvin, an architectural monument of the 18th century was moved, too.[16]

The stadium was officially opened on 31 July 1956,[17] with a friendly football match between the RSFSR and China. 100 thousand spectators welcomed the event.[18][19] The stadium was built in just 450 days. It was the national stadium of the Soviet Union, and is now the national stadium of Russia.[20] In 1960 a 26-foot bronze statue of Lenin by sculptor Matvei Manizer, which was created for Expo 58 in Brussel, was placed on the square in front of the main stadium entrance.[3][21]

1980 Summer Olympics

.jpg.webp)

In 1976–1979 the sports complex was repaired for the first time.[22] The stadium was the chief venue for the 1980 Summer Olympics,[23] the spectator capacity being 103,000 at that time. The events hosted in this stadium were the opening and closing ceremonies, athletics, football finals, and the individual jumping grand prix.[24] Then General Secretary of the CPSU Central Committee and Chairman of the Presidium of the USSR Supreme Soviet Leonid Brezhnev declared the XXII Summer Olympic Games open.[25]

1982 Luzhniki disaster

On 20 October 1982, disaster struck during a UEFA Cup match between FC Spartak Moscow and HFC Haarlem. 66 people died in the stampede,[26] which made it Russia's worst sporting disaster and most famous cover-up at the time.

1990s and 2000s

In the spring of 1992, the state enterprise, including the sports complex, was privatized and renamed the Luzhniki Olympic Complex, and by June of the same year, Lenin's name was removed.[27] An extensive renovation in 1996 saw the construction of a roof over the stands, and the refurbishment of the seating areas, resulting in a decrease in capacity.[17] Till the renovation, the stadium could accommodate 81 thousand people.[28]

In 1998, the stadium was listed by UEFA in the list of 5-star European football stadiums.[29]

The stadium hosted the 1999 UEFA Cup Final in which Parma defeated Marseille in the second UEFA Cup final to be played as a single fixture.[30]

The Luzhniki Stadium was chosen by the UEFA to host the 2008 UEFA Champions League Final won by Manchester United who beat Chelsea in the first all-English Champions League final on 21 May. The match passed incident-free and a spokesman for the British Embassy in Moscow said, "The security and logistical arrangements put in place by the Russian authorities have been first-rate, as has been their cooperation with their visiting counterparts from the UK."[31]

In August 2013, the stadium hosted the World Athletics Championships.[32]

Renovation for FIFA World Cup

The original stadium was demolished in 2013 to give a way for the construction of a new stadium. However, the self-supported cover was retained. The facade wall was retained as well, due to its architectural value, and was later reconnected to the new building. Construction of the new stadium was completed in 2017.[33] The total cost of repairs was 24 billion rubles.[34]

The 2018 FIFA World Cup was held in Russia with the Luzhniki Stadium selected as the venue for the opening match and also the final, which was held on 15 July 2018. For the 2018 World Cup the stadium organized six checkpoints with 39 inspection lanes and seven pedestrian points with 427 points for the passage of spectators. About 900 scanners, 3000 cameras and monitors were installed. Special seats were provided for fans with disabilities.[35] The stadium's capacity was increased from 78,000 to 81,000 seats,[36] partly caused by the removal of the athletics track around the pitch. In 2018 FIFA named the stadium as best arena in the world.[37]

The stadium joins Rome's Stadio Olimpico, London's old Wembley Stadium, Berlin's Olympiastadion and Munich's Olympiastadion as the only stadiums to have hosted the finals of the FIFA World Cup and UEFA's European Cup/Champions League and featured as a main stadium of the Summer Olympic Games. Saint Denis' Stade de France is scheduled to become another in 2024.

Largest sport events

- 1956 – Summer Spartakiad of the Peoples of the USSR.

- 1957 – Ice Hockey World Championship.

- 1957 – VI World Festival of Youth and Students.

- 1960 – Ice Speedway World Championship.

- 1961 – World Modern Pentathlon Championship.

- 1962 – World Speed Skating Championship.

- 1973 – Summer Universiade.

- 1974 – World Modern Pentathlon Championship.

- 1979 – VII Spartakiad of the Peoples of the USSR.

- 1980 – Summer Olympic Games, including opening and closing ceremonies.

- 1984 – Friendship Games, including opening and closing ceremonies.

- 1985 – XII World Festival of Youth and Students.

- 1986 – Goodwill Games, including the opening ceremony.

- 1997 – Russia vs. FIFA team in honor of the 850th anniversary of Moscow, the 100th anniversary of Russian football and the opening after the reconstruction of the Luzhniki stadium.

- 1998 – First World Youth Games, including the opening ceremony.

- 1999 – UEFA Cup final: Olympique de Marseille (France) vs. Parma (Italy).

- 2008 – UEFA Champions League final: Manchester United (England) vs. Chelsea (England)

- 2013 – Rugby World Cup Sevens.

- 2013 – World Championships in Athletics.

- 2018 – FIFA World Cup, including the final match.

Concerts and other events

- 1987 – Festival of Soviet-Indian Friendship.

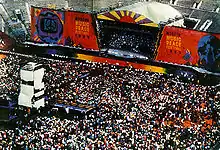

- 12–13 August 1989 – The Moscow Music Peace Festival was held at the stadium. Bands such as Bon Jovi, Scorpions, Ozzy Osbourne, Skid Row, Mötley Crüe, Cinderella, Gorky Park took part in the event.

- 24 June 1990 – As part of the festival of the newspaper Moskovsky Komsomolets, the last concert of Viktor Tsoi and Kino took place.

- 29 June 1991 – As part of the holiday of the newspaper Moskovsky Komsomolets Oleg Gazmanov took part in the concert. It was the last time the Olympic flame was lit at the stadium.

- 20 June 1992 – A concert took place in memory of Viktor Tsoi. DDT, Alisa, Nautilus Pompilius, Joanna Stingray, Brigada S, Chaif, Kalinov Most, and others took part in the event.

- 15 September 1993 – A concert by Michael Jackson took place as part of the Dangerous World Tour; this was Jackson's first performance in Russia.[38]

- 11 August 1998 – The Rolling Stones performed at the stadium for the first time in Russia.

- 28 February 2003 – Agata Kristi played a concert in honour of its 15th anniversary.

- 12 September 2006 – Madonna came to Russia and performed at the stadium for the first time, as part of her world Confessions Tour.

- 18 July 2007 – Metallica played a concert at the stadium for the first time, 16 years after the first arrival in Russia, as part of the Sick of the Studio '07 tour.

- 26 July 2008 – The holiday "MosKomSport – 85 years" was held. During it a concert took place, in which the bands U-Piter, Chaif, Crematory, and others took part.

- 25 August 2010 – A U2 concert took place as part of the U2 360° Tour.[39]

- 22 July 2012 – The Red Hot Chili Peppers with the support of Gogol Bordello gave a concert on the stage of the complex.[40]

- 2011–2013 – A musical competition Factor A was held in the complex.

- 31 May 2014 – A concert of the Mashina Vremeni dedicated to the band's 45th anniversary was held in front of the stadium, which was closed for the renovation.

- 29 August 2018 – Imagine Dragons performed at the stadium as part of the Evolve World Tour.[41]

- 29 July 2019 – Rammstein performed during the European half of the Rammstein Stadium Tour.[42]

Notable events

_%C2%B7_1.jpg.webp)

When the Luzhniki Stadium hosted the final game of the 1957 Ice Hockey World Championship between Sweden and the Soviet Union, it was attended by a crowd of 55,000 and set a new world record at the time.[43] On 23 May 1963, Fidel Castro made a historic speech in Luzhniki Stadium during his record 38-day visit to the Soviet Union.[44]

New Japan Pro-Wrestling, the Japanese professional wrestling promotion, ran a show in 1989.[45] Luzhniki Stadium also makes an appearance in the Russian supernatural thriller film Night Watch (Russian: Ночной дозор, Nochnoy Dozor), during the power shut-down scene when the power station goes into overload. The stadium is seen with a match taking place, and then the lights go out.

In 2008, Manchester United beat Chelsea on penalties after a 1–1 draw to win their third European Cup. This was United's third appearance in the final, and Chelsea's first.[7]

On 18 March 2022, Russian president Vladimir Putin held a rally at the stadium marking the eighth anniversary of the annexation of Crimea by the Russian Federation and to draw support for Russia's invasion of Ukraine. It was attended by approximately 200,000 supporters, according to police, with media reports suggesting that state employees were bussed to the rally while others were paid or forced to attend.[46][47]

2018 FIFA World Cup

Luzhniki Stadium hosted seven games of the 2018 FIFA World Cup, including the opening and the final matches.

| Date | Time | Team No. 1 | Result | Team No. 2 | Round | Attendance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14 June 2018 | 18:00 | 5–0 | Group A (opening match) | 78,011[48][49][50][51][52][53][54] | ||

| 17 June 2018 | 18:00 | 0–1 | Group F | |||

| 20 June 2018 | 15:00 | 1–0 | Group B | |||

| 26 June 2018 | 17:00 | 0–0 | Group C | |||

| 1 July 2018 | 17:00 | 1–1 (3–4 pen.) | Round of 16 | |||

| 11 July 2018 | 21:00 | 2–1 (a.e.t.) | Semi-final | |||

| 15 July 2018 | 18:00 | 4–2 | Final |

Security measures

During the World Cup, Luzhniki had six access control stations with 39 inspection lines, and seven access control points with 427 entrances for fans arriving on foot. The grounds were serviced by 3,000 surveillance cameras and about 900 scanners, monitors, and detectors.[55]

References

- ↑ "Luzhniki Stadium". FIFA. Archived from the original on 18 November 2015. Retrieved 15 June 2018.

- ↑ "TASS: Sport – Reconstruction of World Cup 2018 opening match stadium to cost 350 mln euros". Special.tass.ru. 9 July 2015. Retrieved 6 June 2018.

- 1 2 "How the Luzhniki Stadium became a monument through 60 years of triumph and tragedy". thesefootballtimes.co. 11 July 2018. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- ↑ "Moscow Football Clubs and Stadiums". football-stadiums.co.uk. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- ↑ "История создания комплекса" [Moscow to host Champions League final on natural grass]. Luzhniki Stadium. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 10 December 2016.

- ↑ "Moscow to host Champions League final on natural grass". ESPN. 5 October 2006. Archived from the original on 26 February 2014.

- 1 2 "Chelsea and Man Utd set for final". bbc.co.uk. 21 May 2008. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- ↑ "Le respect de votre vie privée est notre priorité". eurosport.fr. 21 May 2008. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- ↑ "Breathing life into Architecture. Best engineering and structural solutions". metropolis-group.ru. 12 April 2019. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- ↑ Andrews, Crispin (11 October 2016). "Hybrid football pitches: why the grass is always greener". eandt.theiet.org. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

- ↑ "Luzhniki Stadium reconstruction almost completed". archsovet.msk.ru. 10 May 2017. Retrieved 3 November 2020.

- ↑ "The 1952 Olympic Games, the US, and the USSR". processhistory.org. 8 February 2018. Retrieved 3 November 2020.

- ↑ "The main stadium of the country was coined in 90 days, and built – for the half year". besttopnews.com. 31 July 2009. Retrieved 3 November 2020.

- ↑ "Лужники: осторожно, реконструкция!" (PDF). intelros.ru. Retrieved 3 November 2020.

- ↑ "Putin says renovated stadium deserves being main host for 2018 FIFA World Cup". tass.com. Retrieved 3 November 2020.

- ↑ "1956 2016 Город спорта". ria.ru. 29 July 2016. Retrieved 3 November 2020.

- 1 2 "Luzhniki Stadium". The Stadium Guide.

- ↑ "Главный стадион страны История "Лужников" от замысла до приезда лионеля месси". tass.ru. Retrieved 5 November 2020.

- ↑ "Luzhniki, happy anniversary!". micetimes.asia. 31 July 2016. Retrieved 5 November 2020.

- ↑ "Stadion Luzhniki". stadiumdb.com. Retrieved 5 November 2020.

- ↑ "Lenin statue sandwiched by ads for Budweiser, Visa". timesofisrael.com. 15 July 2018. Retrieved 5 November 2020.

- ↑ "Russia and Argentina re-open Luzhniki Stadium in style". fifa.com. 11 November 2017. Retrieved 6 November 2020.

- ↑ Flanagan, Aaron (22 September 2017). "Russia World Cup final venue completed as new look Luzhniki Stadium is revealed". mirror. Retrieved 7 December 2017.

- ↑ 1980 Summer Olympics official report. Archived 18 November 2008 at the Wayback Machine Volume 2. Part 1. pp. 48–51.

- ↑ "XXII Summer Olympic Games in the Soviet Union". soviet-art.ru. 19 July 2017. Retrieved 6 November 2020.

- ↑ Зайкин, В. (20 July 1989). Трагедия в Лужниках. Факты и вымысел. Известия (in Russian) (202). Archived from the original on 15 September 2018. Retrieved 6 February 2012.

- ↑ "Main stadium of the country". TASS. Moscow. Retrieved 21 October 2020.

- ↑ "2018 World Cup. Luzhniki Stadium by Speech". metalocus.es. 14 June 2018. Retrieved 6 November 2020.

- ↑ "UEFA 5 Star Stadiums". stadiumdb.com. Retrieved 6 November 2020.

- ↑ "Moscow first took the European Cup final in the hungry 1990s. the Rouble then fell 4 times". bestsport.news. 27 March 2020. Retrieved 6 November 2020.

- ↑ Halpin, Tony (22 May 2008). "Moscow proud of trouble-free Champions League final". The Times. London. Retrieved 22 May 2008.

- ↑ "Gallery: Mo Farah stars in 10,000m at 2013 World Athletics Championships in Moscow". metro.co.uk. 10 August 2013. Retrieved 6 November 2020.

- ↑ "Реконструкция Лужников – образец заботы о культурном наследии – мэр". m24.ru.

- ↑ "Luzhniki Stadium's reconstruction for 2018 FIFA World Cup totals $410 mln". tass.com. Retrieved 9 November 2020.

- ↑ "Три тысячи камер и другие факты о подготовке "Лужников" к ЧМ-2018". m24.ru. 6 February 2017. Retrieved 9 November 2020.

- ↑ FIFA.com (1 January 1900). "Luzhniki Stadium blossoms as it prepares for a new chapter". FIFA.com. Archived from the original on 6 March 2017. Retrieved 7 December 2017.

- ↑ "Luzhniki Stadium Named World's Best Football Arena". russianfootballnews.com. 21 March 2018. Retrieved 9 November 2020.

- ↑ https://www.upi.com/Archives/1993/09/15/Jacksons-Moscow-gig-a-success-despite-the-rain/1750748065600/

- ↑ "U2 > News > 'This Extraordinary City...'". www.u2.com. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

- ↑ "Luzniky Stadium". Red Hot Chili Peppers. Archived from the original on 22 February 2014.

- ↑ "Imagine Dragons setlist, Luzhniki Stadium". setlist.fm.

- ↑ "Europe Stadium Tour 2019". Rammstein.

- ↑ "What date and time is the World Cup 2018 final and where will it be?". goal.com. 10 July 2018. Retrieved 9 November 2020.

- ↑ "Castro to Canossa or El Dorado? The Causes, Events, and Impact of Fidel Castro's Journey to the Soviet Union, Spring 1963" (PDF). digital.lib.washington.edu. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 9 November 2020.

- ↑ "The Wrestling Insomniac". thewrestlinginsomniac.com. Retrieved 9 November 2020.

- ↑ Vasilyeva, Nataliya (18 March 2022). "Russian TV cuts off Vladimir Putin mid-speech during major Moscow rally". The Telegraph. London, England. Retrieved 18 March 2022.

- ↑ "Putin Marks Crimea Anniversary, Defends 'Special Operation' in Ukraine in Stadium Rally". The Moscow Times. 18 March 2022.

- ↑ "Match report – Group A – Russia – Saudi Arabia" (PDF). FIFA.com. Fédération Internationale de Football Association. 14 June 2018. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

- ↑ "Match report – Group F – Germany – Mexico" (PDF). FIFA.com. Fédération Internationale de Football Association. 17 June 2018. Retrieved 17 June 2018.

- ↑ "Match report – Group B – Portugal – Morocco" (PDF). FIFA.com. Fédération Internationale de Football Association. 20 June 2018. Retrieved 20 June 2018.

- ↑ "Match report – Group C – Denmark – France" (PDF). FIFA.com. Fédération Internationale de Football Association. 26 June 2018. Retrieved 26 June 2018.

- ↑ "Match report – Round of 16 – Spain – Russia" (PDF). FIFA.com. Fédération Internationale de Football Association. 1 July 2018. Retrieved 1 July 2018.

- ↑ "Match report – Semi-final – Croatia – England" (PDF). FIFA.com. Fédération Internationale de Football Association. 11 July 2018. Retrieved 11 July 2018.

- ↑ "Match report – Final – France – Croatia" (PDF). FIFA.com. Fédération Internationale de Football Association. 15 July 2018. Retrieved 15 July 2018.

- ↑ "Три тысячи камер и другие факты о подготовке "Лужников" к ЧМ-2018".

External links

55°42′57″N 37°33′13″E / 55.71583°N 37.55361°E

| Events and tenants | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by | Summer Universiade Opening and closing ceremonies 1973 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | Summer Olympics Opening and closing ceremonies (Olympic Stadium) 1980 |

Succeeded by Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum Los Angeles |

| Preceded by | Summer Olympics Olympic Athletics competitions Main venue 1980 |

Succeeded by Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum Los Angeles |

| Preceded by | Summer Olympics Men's football final venue 1980 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by Parc des Princes Paris |

UEFA Cup Final venue 1999 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | UEFA Champions League Final venue 2008 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | IAAF World Championships in Athletics Main venue 2013 |

Succeeded by Beijing National Stadium Beijing |

| Preceded by | Rugby World Cup Sevens Men's venue 2013 |

Succeeded by AT&T Park San Francisco |

| Preceded by | FIFA World Cup Opening venue 2018 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | FIFA World Cup Final venue 2018 |

Succeeded by |