Meantone temperaments are musical temperaments, that is a variety of tuning systems, obtained by narrowing the fifths so that their ratio is slightly less than 3:2 (making them narrower than a perfect fifth), in order to push the thirds closer to pure. Meantone temperaments are constructed similarly to Pythagorean tuning, as a stack of equal fifths, but they are temperaments in that the fifths are not pure.

Notable meantone temperaments

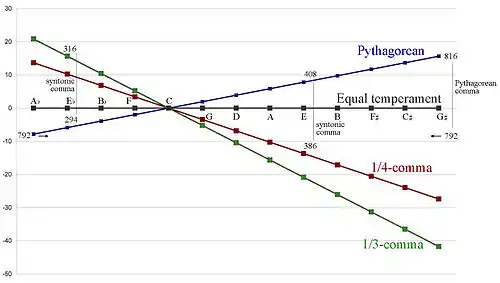

Equal temperament, obtained by making all semitones the same size, each equal to one-twelfth of an octave (with ratio the 12th root of 2 to one ( 12√2 : 1 ), narrows the fifths by about 2 cents or 1/ 12 of a Pythagorean comma, and produces out-of-tune thirds that are only slightly better than in Pythagorean tuning. Equal temperament is roughly the same as 1/ 11 comma meantone tuning.

Quarter-comma meantone, which tempers each of the twelve fifths by 1 / 4 of a syntonic comma, is the best known type of meantone temperament, and the term meantone temperament is often used to refer to it specifically. Four ascending fifths (as C G D A E B) tempered by 1 / 4 comma produce a perfect major third (C E), one syntonic comma narrower than the Pythagorean third that would result from four perfect fifths. Quarter-comma meantone has been practiced from the early 16th century to the end of the 19th. It can be approximated by a division of the octave in 31 equal steps.

This proceeds in the same way as Pythagorean tuning; i.e., it takes the fundamental (say, C) and goes up by six successive fifths (always adjusting by dividing by powers of 2 to remain within the octave above the fundamental), and similarly down, by six successive fifths (adjusting back to the octave by multiplying by powers of 2 ). However, instead of using the 3 / 2 ratio, which gives "perfect" fifths, this must be multiplied by the fourth root of 81 / 80 . ( 81 / 80 is the "syntonic comma": the ratio of a just major third ( 5 / 4 ) to a Pythagorean third ( 81 / 64 ).) Equivalently, one can use 4√5 instead of 3 / 2 , to produce slightly reduced fifths. This results in the interval C E being a "perfect third" ( 5 / 4 ), and the intermediate seconds (C D, D E) dividing C E uniformly, so D C and E-D are equal ratios, whose square is 5 / 4 . The same is true of the major second sequences F G A and G A B. However, there is still a "comma" in meantone tuning (i.e. the F♯ and the G♭ have different pitches; they are not the same as in 12 TET). The meantone comma is actually larger than the Pythagorean one, and in the opposite pitch direction (sharp vs. flat).

In third-comma meantone, the fifths are tempered by 1 / 3 comma, and three descending fifths (such as A D G C) produce a perfect minor third (A C) one syntonic comma wider than the Pythagorean comma that would result from three perfect fifths. Third-comma meantone can be approximated extremely well by a division of the octave in 19 equal steps.

The tone as a mean

The name "meantone temperament" derives from the fact that all such temperaments have only one size of the tone, between the major tone (8:9) and minor tone (9:10) of just intonation, which differ by a syntonic comma. In any regular system (i.e. with all fifths but one of the same size)[1] the tone (as C–D) is reached after two fifths (as C–G–D), while the major third is reached after four fifths: the tone therefore is exactly half the major third.

This is one sense in which the tone is a mean.

In the case of quarter-comma meantone, in addition, where the major third is made narrower by a syntonic comma, the tone is also half a comma narrower than the major tone of just intonation, or half a comma wider than the minor tone: this is another sense in which the tone in quarter-tone temperament may be considered a mean tone, and it explains why quarter-comma meantone is often considered the meantone temperament properly speaking.[2]

Meantone temperaments

"Meantone" can receive the following equivalent definitions:

- The meantone is the geometric mean between the major whole tone (9:8 in just intonation) and the minor whole tone (10:9 in just intonation).

- The meantone is the mean of its major third (for instance the square root of 5:4 in quarter-comma meantone).

The family of meantone temperaments share the common characteristic that they form a stack of identical fifths, the whole tone (major second) being the result of two fifths minus one octave, the major third of four fifths minus two octaves. Meantone temperaments are often described by the fraction of the syntonic comma by which the fifths are tempered: quarter-comma meantone, the most common type, tempers the fifths by 1 / 4 of a syntonic comma, with the result that four fifths produce a just major third, a syntonic comma lower than a Pythagorean major third; third-comma meantone tempers by 1 / 3 of a syntonic comma, three fifths producing a just major sixth (and hence a just minor 3rd), a syntonic comma lower than a Pythagorean one.

A meantone temperament is a linear temperament, distinguished by the width of its generator (the fifth, often measured in cents). Historically notable meantone temperaments, discussed below, occupy a narrow portion of this tuning continuum, with fifths ranging from approximately 695 to 699 cents.

Meantone temperaments can be specified in various ways: By what fraction (logarithmically) of a syntonic comma the fifth is being flattened (as above), what equal temperament has the meantone fifth in question, the width of the tempered perfect fifth in cents, or the ratio of the whole tone to the diatonic semitone. This last ratio was termed " R " by American composer, pianist and theoretician Easley Blackwood, but in effect has been in use for much longer than that. The ratio is useful because it gives an idea of the melodic qualities of the tuning, and if R happens to be a rational number N / D , then so is 3 R + 1 / 5 R + 2 or 3 N + D / 5 N + 2 D , which gives an idea of the size of fifth, in terms of logarithms base 2, and which immediately tells us what division of the octave we will have.

If we multiply by 1200 ¢, we have the size of fifth in cents.

In these terms, some historically notable meantone tunings are listed below. The second and fourth column are corresponding approximations to the first column. The third column shows how close the second column's approximation is to the actual size of the fifth interval in the given meantone tuning from the first column.

| Fraction of a (syntonic) comma |

Pure interval | Approximate size of the fifth (in octaves) |

Error (in cents) |

Blackwood’s ratio ( R ) |

Approximate ET tones |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1/ 315 (extended very nearly |

3311 × 5 / 2495 (≈ perfect fifth, ≈ major whole tone) For all practical purposes, |

31 / 53 | +0.000066

(+6.55227×10−5) |

9 / 4 = 2.25 | 53 |

|

1/ 11 (1/ 12 Pythagorean comma) |

16384 / 10935 ( 214 / 37 × 5 ) (Kirnberger fifth, a just fifth |

7 / 12 | +0.000116

(+1.16371×10−4) |

2 / 1 = 2.00 | 12 |

| 1 / 6 |

45 / 32 and 64 / 45 (tritones) |

32 / 55 | −0.188801 | 9 / 5 = 1.80 | 55 |

| 1 / 5 |

15/ 8 and 16 / 15 (diatonic semitone) |

25 / 43 | +0.0206757 | 7 / 4 = 1.75 | 43 |

| 1 / 4 |

5 / 4 and 8 / 5 (major third) |

18 / 31 | +0.195765 | 5 / 3 = 1.66 | 31 |

| 2 / 7 |

25 / 24 and 48 / 25 (chromatic semitone) |

29 / 50 | +0.189653 | 8 / 5 = 1.60 | 50 |

| 1 / 3 |

5 / 3 and 6 / 5 (minor third) |

11 / 19 | −0.0493956 | 3 / 2 = 1.50 | 19 |

| 1 / 2 |

9 / 5 and 10/ 9 (minor whole tone) |

19 / 33 | −0.292765 | 4 / 3 = 1.33 | 33 |

Equal temperaments

Neither the just fifth nor the quarter-comma meantone fifth is a rational fraction of the octave, but several tunings exist which approximate the fifth by such an interval; these are a subset of the equal temperaments ( "N TET" ), in which the octave is divided into some number (N) of equally wide intervals.

Equal temperaments useful as meantone tunings include (in order of increasing generator width) 19 TET (~ + 1 / 3 comma), 50 TET (~ + 2 / 7 comma), 31 TET (~ + 1 / 4 comma), 43 TET (~ + 1 / 5 comma), and 55 TET (~ + 1 / 6 comma). The farther the tuning gets away from quarter-comma meantone, however, the less related the tuning is to harmonic timbres, which can be overcome by tempering the partials to match the tuning – which is possible, however, only on electronic synthesizers.[3]

Wolf intervals

A whole number of just perfect fifths will never add up to a whole number of octaves, because log2(3) is an irrational number. If a stacked-up whole number of perfect fifths is too close with the octave, then one of the intervals that is enharmonically equivalent to a fifth must have a different width than the other fifths. For example, to make a 12-note chromatic scale in Pythagorean tuning close at the octave, one of the fifth intervals must be lowered ("out-of-tune") by the Pythagorean comma; this altered fifth is called a "wolf fifth" because it sounds similar to a fifth in its interval size and seems like an out-of-tune fifth, but is actually a diminished sixth (e.g. between G♯ and E♭). Likewise, 11 of the 12 perfect fourths are also in tune, but the remaining fourth becomes an augmented third.

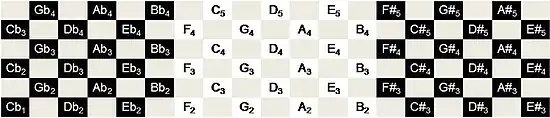

Wolf intervals are an artifact of keyboard design.[4] This can be shown most easily using an isomorphic keyboard, such as that shown in Figure 2.

On an isomorphic keyboard, any given musical interval has the same shape wherever it appears, except at the edges. Here's an example. On the keyboard shown in Figure 2, from any given note, the note that's a perfect fifth higher is always up-and-rightwardly adjacent to the given note. There are no wolf intervals within the note-span of this keyboard. The problem is at the edge, on the note E♯. The note that's a perfect fifth higher than E♯ is B♯, which is not included on the keyboard shown (although it could be included in a larger keyboard, placed just to the right of A♯, hence maintaining the keyboard's consistent note-pattern). Because there is no B♯ button, when playing an E♯ power chord, one must choose some other note, such as C, to play instead of the missing B♯.

Even edge conditions produce wolf intervals only if the isomorphic keyboard has fewer buttons per octave than the tuning has enharmonically-distinct notes (Milne, 2007). For example, the isomorphic keyboard in Figure 2 has 19 buttons per octave, so the above-cited edge-condition, from E♯ to C, is not a wolf interval in 12-ET, 17-ET, or 19-ET; however, it is a wolf interval in 26-ET, 31-ET, and 50-ET. In these latter tunings, using electronic transposition could keep the current key's notes on the isomorphic keyboard's white buttons, such that these wolf intervals would very rarely be encountered in tonal music, despite modulation to exotic keys.[5]

Isomorphic keyboards expose the invariant properties of the meantone tunings of the syntonic temperament isomorphically (that is, for example, by exposing a given interval with a single consistent inter-button shape in every octave, key, and tuning) because both the isomorphic keyboard and temperament are two-dimensional (i.e., rank-2) entities (Milne, 2007). One-dimensional N-key keyboards can expose accurately the invariant properties of only a single one-dimensional N-ET tuning; hence, the one-dimensional piano-style keyboard, with 12 keys per octave, can expose the invariant properties of only one tuning: 12-ET.

When the perfect fifth is exactly 700 cents wide (that is, tempered by approximately 1⁄11 of a syntonic comma, or exactly 1⁄12 of a Pythagorean comma) then the tuning is identical to the familiar 12-tone equal temperament. This appears in the table above when R = 2:1.

Because of the compromises (and wolf intervals) forced on meantone tunings by the one-dimensional piano-style keyboard, well temperaments and eventually equal temperament became more popular.

Using standard interval names, twelve fifths equal six octaves plus one augmented seventh; seven octaves are equal to eleven fifths plus one diminished sixth. Given this, three "minor thirds" are actually augmented seconds (for example, B♭ to C♯), and four "major thirds" are actually diminished fourths (for example, B to E♭). Several triads (like B–E♭–F♯ and B♭–C♯–F) contain both these intervals and have normal fifths.

Extended meantones

All meantone tunings fall into the valid tuning range of the syntonic temperament, so all meantone tunings are syntonic tunings. All syntonic tunings, including the meantones, have a conceptually infinite number of notes in each octave, that is, seven natural notes, seven sharp notes (F♯ to B♯), seven flat notes (B♭ to F♭), double sharp notes, double flat notes, triple sharps and flats, and so on. In fact, double sharps and flats are uncommon, but still needed; triple sharps and flats are almost never seen. In any syntonic tuning that happens to divide the octave into a small number of equally wide smallest intervals (such as 12, 19, or 31), this infinity of notes still exists, although some notes will be equivalent. For example, in 19-ET, E♯ and F♭ are the same pitch.

Many musical instruments are capable of very fine distinctions of pitch, such as the human voice, the trombone, unfretted strings such as the violin, and lutes with tied frets. These instruments are well-suited to the use of meantone tunings.

On the other hand, the piano keyboard has only twelve physical note-controlling devices per octave, making it poorly suited to any tunings other than 12-ET. Almost all of the historic problems with the meantone temperament are caused by the attempt to map meantone's infinite number of notes per octave to a finite number of piano keys. This is, for example, the source of the "wolf fifth" discussed above. When choosing which notes to map to the piano's black keys, it is convenient to choose those notes that are common to a small number of closely related keys, but this will only work up to the edge of the octave; when wrapping around to the next octave, one must use a "wolf fifth" that is not as wide as the others, as discussed above.

The existence of the "wolf fifth" is one of the reasons why, before the introduction of well temperament, instrumental music generally stayed in a number of "safe" tonalities that did not involve the "wolf fifth" (which was generally put between G♯ and E♭).

Throughout the Renaissance and Enlightenment, theorists as varied as Nicola Vicentino, Francisco de Salinas, Fabio Colonna, Marin Mersenne, Christiaan Huygens, and Isaac Newton advocated the use of meantone tunings that were extended beyond the keyboard's twelve notes,[6][7][8] and hence have come to be called "extended" meantone tunings. These efforts required a concomitant extension of keyboard instruments to offer means of controlling more than 12 notes per octave, including Vincento's Archicembalo, Mersenne's 19-ET harpsichord, Colonna's 31-ET sambuca, and Huygens's 31-ET harpsichord.[9] Other instruments extended the keyboard by only a few notes. Some period harpsichords and organs have split D♯/E♭ keys, such that both E major/C♯ minor (4 sharps) and E♭ major/C minor (3 flats) can be played without wolf fifths. Many of those instruments also have split G♯/A♭ keys, and a few have all the five accidental keys split.

All of these alternative instruments were "complicated" and "cumbersome" (Isacoff, 2003), due to (a) not being isomorphic, and (b) not having the ability to transpose electronically, which can significantly reduce the number of note-controlling buttons needed on an isomorphic keyboard (Plamondon, 2009). Both of these criticisms could be addressed by electronic isomorphic keyboard instruments (such as the open-source hardware jammer keyboard), which could be simpler, less cumbersome, and more expressive than existing keyboard instruments.[10]

Use of meantone temperament

References to tuning systems that could possibly refer to meantone were published as early as the 1496 text Practicae musica by Franchinus Gaffurius. Pietro Aron was unmistakably discussing quarter-comma meantone in his 1523 book Toscanello in musica. However, the first mathematically precise meantone tuning descriptions are found in late 16th century treatises by Gioseffo Zarlino (Le istitutioni harmoniche, 1558) and Francisco de Salinas (De musica libri septem, 1577). These authors both described the 1/4-comma, 1/3-comma and 2/7 comma meantone systems. Lodovico Fogliano mentioned the quarter-comma system, but offered no discussion of it.

Of course, the quarter comma meantone system (or any other meantone system) could not have been implemented with complete accuracy until much later, since devices that could accurately measure pitch frequencies didn't exist until the mid-19th century. But tuners could use precisely the same method that "by ear" tuners have used until recently: go up by fifths, and down by octaves, or down by fifths, and up by octaves, and "temper" the fifths so they are "slightly" smaller than 3/2's.

For 12 tone equitempered tuning, they would have to be tempered by a little less than a "1/4 comma", since they must form a perfect cycle, with no comma at the end, whereas the "Mean" tuning still has a residual comma.

How tuners could identify a "quarter comma" reliably by ear is a bit more subtle. Since this amounts to about 0.3% of the frequency which, near middle C (~264 Hz), is about one Hertz, they could do it by using perfect fifths as a reference and adjusting the tempered note to produce beats at this rate. However, the frequency of the beats would have to be slightly adjusted, proportionately to the frequency of the note.

In the past, meantone temperaments were sometimes used or referred to under other names or descriptions. For example, in 1691 Christiaan Huygens wrote his "Lettre touchant le cycle harmonique" ("Letter concerning the harmonic cycle") with the purpose of introducing what he believed to be a new division of the octave. In this letter Huygens referred several times, in a comparative way, to a conventional tuning arrangement, which he indicated variously as "temperament ordinaire", or "the one that everyone uses". But Huygens' description of this conventional arrangement was quite precise, and is clearly identifiable with what is now classified as (quarter-comma) meantone temperament.[11]

Although meantone is best known as a tuning environment associated with earlier music of the Renaissance and Baroque, there is evidence of continuous usage of meantone as a keyboard temperament well into the middle of the 19th century.[12] Meantone temperament has had considerable revival for early music performance in the late 20th century and in newly composed works specifically demanding meantone by composers including John Adams, György Ligeti and Douglas Leedy.

See also

References

- ↑ J. Murray Barbour, Tuning and Temperament. A Historical Survey. East Lansing, 1951, p. xi.

- ↑ Barbour 1951, p. x and pp. 25-44.

- ↑ Sethares, W.A.; Milne, A.; Tiedje, S.; Prechtl, A.; Plamondon, J. (2009). "Spectral tools for dynamic tonality and audio morphing". Computer Music Journal. 33 (2): 71–84. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.159.838. doi:10.1162/comj.2009.33.2.71. S2CID 216636537. Retrieved 2009-09-20 – via Johns Hopkins University (muse.jhu.edu).

- ↑ Milne, Andrew; Sethares, W.A.; Plamondon, J. (March 2008). "Tuning Continua and Keyboard Layouts". Journal of Mathematics and Music. 2 (1): 1–19. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.158.6927. doi:10.1080/17459730701828677. S2CID 1549755.

- ↑ Plamondon, Jim; Milne, A.; Sethares, W.A. (2009). "Dynamic Tonality: Extending the Framework of Tonality into the 21st Century" (PDF). Proceedings of the Annual Conference of the South Central Chapter of the College Music Society.

- ↑ Barbour, J.M., 2004, Tuning and Temperament: A Historical Survey.

- ↑ Duffin, R.W., 2006, How Equal Temperament Ruined Harmony (and Why You Should Care).

- ↑ Isacoff, Stuart, 2003, Temperament: How Music Became a Battleground for the Great Minds of Western Civilization

- ↑ Stembridge, Christopher (1993). "The Cimbalo Cromatico and Other Italian Keyboard Instruments with Nineteen or More Divisions to the Octave". Performance Practice Review. vi (1): 33–59. doi:10.5642/perfpr.199306.01.02.

- ↑ Paine, G.; Stevenson, I.; Pearce, A. (2007). "The Thummer Mapping Project (ThuMP)" (PDF). Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on New Interfaces for Musical Expression (NIME07): 70–77.

- ↑ (See references cited in article 'Temperament Ordinaire'.)

- ↑ George Grove wrote as late as 1890: "The mode of tuning which prevailed before the introduction of equal temperament, is called the Meantone System. It has hardly yet died out in England, for it may still be heard on a few organs in country churches. According to Don B. Yñiguez, organist of Seville Cathedral, the meantone system is generally maintained on Spanish organs, even at the present day." A Dictionary of Music and Musicians, Macmillan, London, vol. IV, 1890 [1st edition], p. 72.

External links

- An explanation of constructing Quarter Comma Meantone Tuning

- LucyTuning - specific meantone derived from pi, and the writings of John Harrison

- How to tune quarter-comma meantone

- Archive index at the Wayback Machine Music fragments played in different temperaments - mp3s not archived

- Kyle Gann's Introduction to Historical Tunings has an explanation of how the meantone temperament works.

- Willem Kroesbergen, Andrew cruickshank: Meantone, unequal and equal temperament during J.S. Bach's life https://www.academia.edu/9189419/Blankenburg_Equal_or_unequal_temperament_during_J.S._Bach_s_life