The median voter theorem is a theorem applying to single-winner elections relating to ranked preference voting put forward by Duncan Black in 1948.[1] It states that if voters and policies are distributed along a one-dimensional spectrum, with voters ranking alternatives in order of proximity, then any voting method which satisfies the Condorcet criterion will elect the candidate closest to the median voter. In particular, a majority vote between two options will do so, such as two-party system.

The theorem is associated with public choice economics and statistical political science. Partha Dasgupta and Eric Maskin have argued that it provides a powerful justification for voting methods based on the Condorcet criterion.[2] Plott's majority rule equilibrium theorem extends this to two dimensions.

A loosely related assertion had been made earlier (in 1929) by Harold Hotelling.[3] It is not a true theorem and is more properly known as the median voter theory or median voter model. It says that in a representative democracy, politicians will converge to the viewpoint of the median voter.[4]

Statement and proof of the theorem

Consider a group of voters who have to elect one from a set of two or more candidates. For simplicity, assume that the number of voters is odd.

The elections are one-dimensional. This means that the opinions of both candidates and voters are distributed along a one-dimensional spectrum, and each voter ranks the candidates in an order of proximity, such that the candidate closest to the voter receives their first preference, the next closest receives their second preference, and so forth.

A Condorcet winner is a candidate who is preferred over every other candidate by a majority of voters. In general elections, a Condorcet winner might not exist. The median voter theorem says that:

- In one-dimensional elections, there a Condorcet winner always exists;

- The Condorcet winner is the candidate closest to the median voter.

In the above example, the median voter is denoted by M, and the candidate closest to him is C, so the median voter theorem says that C is the Condorcet winner. It follows that Charles will win any election conducted using a method satisfying the Condorcet criterion. In particular, when there are only two candidates, the majority rule satisfies the Condorcet criterion; for multiway votes, several methods satisfy it (see Condorcet method).

Proof sketch:Let the median voter be Marlene. The candidate who is closest to her will receive her first preference vote. Suppose that this candidate is Charles and that he lies to her left. Then Marlene and all voters to her left (comprising a majority of the electorate) will prefer Charles to all candidates to his right, and Marlene and all voters to her right will prefer Charles to all candidates to his left.

Extensions

- The theorem also applies when the number of voters is even, but the details depend on how ties are resolved.

- The assumption that preferences are cast in order of proximity can be relaxed to say merely that they are single-peaked.[5]

- The assumption that opinions lie along a real line can be relaxed to allow more general topologies.[6]

- Spatial / valence models: Suppose that each candidate has a valence (attractiveness) in addition to his or her position in space, and suppose that voter i ranks candidates j in decreasing order of vj – dij where vj is j 's valence and dij is the distance from i to j. Then the median voter theorem still applies: Condorcet methods will elect the candidate voted for by the median voter.

History

The theorem was first set out by Duncan Black in 1948. He wrote that he saw a large gap in economic theory concerning how voting determines the outcome of decisions, including political decisions. Black's paper triggered research on how economics can explain voting systems. In 1957 Anthony Downs expounded upon the median voter theorem in his book An Economic Theory of Democracy.[7]

The median voter property

We will say that a voting method has the "median voter property in one dimension" if it always elects the candidate closest to the median voter under a one-dimensional spatial model. We may summarise the median voter theorem as saying that all Condorcet methods possess the median voter property in one dimension.

It turns out that Condorcet methods are not unique in this: Coombs' method is not Condorcet-consistent but nonetheless satisfies the median voter property in one dimension.[8]

Extension to distributions in more than one dimension

The median voter theorem applies in a restricted form to distributions of voter opinions in spaces of any dimension. A distribution in more than one dimension does not necessarily have a median in all directions (which might be termed an 'omnidirectional median'); however a broad class of rotationally symmetric distributions, including the Gaussian, does have a median of this sort.[9] Whenever the distribution of voters has a unique median in all directions, and voters rank candidates in order of proximity, the median voter theorem applies: the candidate closest to the median will have a majority preference over all his or her rivals, and will be elected by any voting method satisfying the median voter property in one dimension.[10] (Uniqueness here generalises the property guaranteed by oddness of sample size in a single dimension.)

It follows that all Condorcet methods – and also Coombs' – satisfy the median voter property in spaces of any dimension for voter distributions with omnidirectional medians.

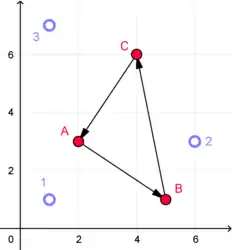

It is easy to construct voter distributions which do not have a median in all directions. The simplest example consists of a distribution limited to 3 points not lying in a straight line, such as 1, 2 and 3 in the second diagram. Each voter location coincides with the median under a certain set of one-dimensional projections. If A, B and C are the candidates, then '1' will vote A-B-C, '2' will vote B-C-A, and '3' will vote C-A-B, giving a Condorcet cycle. This is the subject of the McKelvey–Schofield theorem.

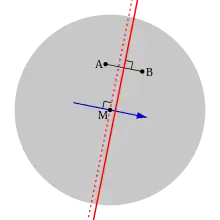

Proof. See the diagram, in which the grey disc represents the voter distribution as uniform over a circle and M is the median in all directions. Let A and B be two candidates, of whom A is the closer to the median. Then the voters who rank A above B are precisely the ones to the left (i.e. the 'A' side) of the solid red line; and since A is closer than B to M, the median is also to the left of this line.

Now, since M is a median in all directions, it coincides with the one-dimensional median in the particular case of the direction shown by the blue arrow, which is perpendicular to the solid red line. Thus if we draw a broken red line through M, perpendicular to the blue arrow, then we can say that half the voters lie to the left of this line. But since this line is itself to the left of the solid red line, it follows that more than half of the voters will rank A above B.

Relation between the median in all directions and the geometric median

Whenever a unique omnidirectional median exists, it determines the result of Condorcet voting methods. At the same time the geometric median can be identified as the ideal winner of a ranked preference election (see Comparison of electoral systems). It is therefore important to know the relationship between the two. In fact whenever a median in all directions exists (at least for the case of discrete distributions), it coincides with the geometric median.

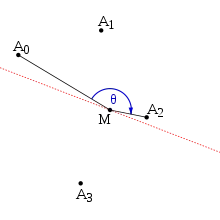

Lemma. Whenever a discrete distribution has a median M in all directions, the data points not located at M must come in balanced pairs (A,A ' ) on either side of M with the property that A – M – A ' is a straight line (ie. not like A 0 – M – A 2 in the diagram).

Proof. This result was proved algebraically by Charles Plott in 1967.[11] Here we give a simple geometric proof by contradiction in two dimensions.

Suppose, on the contrary, that there is a set of points Ai which have M as median in all directions, but for which the points not coincident with M do not come in balanced pairs. Then we may remove from this set any points at M, and any balanced pairs about M, without M ceasing to be a median in any direction; so M remains an omnidirectional median.

If the number of remaining points is odd, then we can easily draw a line through M such that the majority of points lie on one side of it, contradicting the median property of M.

If the number is even, say 2n, then we can label the points A 0, A1,... in clockwise order about M starting at any point (see the diagram). Let θ be the angle subtended by the arc from M –A 0 to M –A n . Then if θ < 180° as shown, we can draw a line similar to the broken red line through M which has the majority of data points on one side of it, again contradicting the median property of M ; whereas if θ > 180° the same applies with the majority of points on the other side. And if θ = 180°, then A 0 and A n form a balanced pair, contradicting another assumption.

Theorem. Whenever a discrete distribution has a median M in all directions, it coincides with its geometric median.

Proof. The sum of distances from any point P to a set of data points in balanced pairs (A,A ' ) is the sum of the lengths A – P – A '. Each individual length of this form is minimised over P when the line is straight, as happens when P coincides with M. The sum of distances from P to any data points located at M is likewise minimised when P and M coincide. Thus the sum of distances from the data points to P is minimised when P coincides with M .

Hotelling's law

A more informal assertion – the median voter model – is related to Harold Hotelling's 'principle of minimum differentiation', also known as 'Hotelling's law'. It states that politicians gravitate toward the position occupied by the median voter, or more generally toward the position favored by the electoral system. It was first put forward (as an observation, without any claim to rigor) by Hotelling in 1929.[3]

Hotelling saw the behavior of politicians through the eyes of an economist. He was struck by the fact that shops selling a particular good often congregate in the same part of a town, and saw this as analogous the convergence of political parties. In both cases it may be a rational policy for maximizing market share.

As with any characterization of human motivation it depends on psychological factors which are not easily predictable, and is subject to many exceptions. It is also contingent on the voting system: politicians will not converge to the median voter unless the electoral process does so.

Uses of the median voter theorem

The theorem is valuable for the light it sheds on the optimality (and the limits to the optimality) of certain voting systems.

Valerio Dotti points out broader areas of application:

The Median Voter Theorem proved extremely popular in the Political Economy literature. The main reason is that it can be adopted to derive testable implications about the relationship between some characteristics of the voting population and the policy outcome, abstracting from other features of the political process.[10]

He adds that...

The median voter result has been applied to an incredible variety of questions. Examples are the analysis of the relationship between income inequality and size of governmental intervention in redistributive policies (Meltzer and Richard, 1981),[12] the study of the determinants of immigration policies (Razin and Sadka, 1999),[13] of the extent of taxation on different types of income (Bassetto and Benhabib, 2006),[14] and many more.

See also

References

- ↑ Black, Duncan (1948-02-01). "On the Rationale of Group Decision-making". Journal of Political Economy. 56 (1): 23–34. doi:10.1086/256633. ISSN 0022-3808.

- ↑ P. Dasgupta and E. Maskin, "The fairest vote of all" (2004); "On the Robustness of Majority Rule" (2008).

- 1 2 Hotelling, Harold (1929). "Stability in Competition". The Economic Journal. 39 (153): 41–57. doi:10.2307/2224214. JSTOR 2224214.

- ↑ Holcombe, Randall G. (2006). Public Sector Economics: The Role of Government in the American Economy. p. 155. ISBN 9780131450424.

- ↑ See Black's paper.

- ↑ Berno Buechel, "Condorcet winners on median spaces" (2014).

- ↑ Anthony Downs, "An Economic Theory of Democracy" (1957).

- ↑ B. Grofman and S. L. Feld, "If you like the alternative vote (a.k.a. the instant runoff), then you ought to know about the Coombs rule" (2004).

- ↑ To be precise, it is the sample distribution of voter opinions which is relevant, and this is necessarily discrete. Results on continuous distributions are of interest only as indicating idealised or approximate behaviour of large samples.

- 1 2 See Valerio Dotti's thesis "Multidimensional Voting Models" (2016).

- ↑ C. R. Plott, "A Notion of Equilibrium and its Possibility Under Majority Rule" (1967).

- ↑ A. H. Meltzer and S. F. Richard, "A Rational Theory of the Size of Government" (1981).

- ↑ A. Razin and E. Sadka "Migration and Pension with International Capital Mobility" (1999).

- ↑ M. Bassetto and J. Benhabib, "Redistribution, Taxes, and the Median Voter" (2006).

Further reading

- Buchanan, James M.; Tollison, Robert D. (1984). The Theory of Public Choice. Vol. II. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0472080415.

- Clinton, Joshua D. (2006). "Representation in Congress: Constituents and the Roll Calls in the 106th House". Journal of Politics. 68 (2): 397–409. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2508.2006.00415.x.

- Congleton, Roger (2003). "The Median Voter Model" (PDF). In Rowley, C. K.; Schneider, F. (eds.). The Encyclopedia of Public Choice. Kluwer Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-7923-8607-0.

- Dasgupta, Partha and Eric Maskin, "On the Robustness of Majority Rule", Journal of the European Economic Association, 2008.

- Downs, Anthony (1957). "An Economic Theory of Political Action in a Democracy". Journal of Political Economy. 65 (2): 135–150. doi:10.1086/257897. S2CID 154363730.

- Holcombe, Randall G. (1980). "An Empirical Test of the Median Voter Model". Economic Inquiry. 18 (2): 260–275. doi:10.1111/j.1465-7295.1980.tb00574.x.

- Holcombe, Randall G.; Sobel, Russell S. (1995). "Empirical Evidence on the Publicness of State Legislative Activities". Public Choice. 83 (1–2): 47–58. doi:10.1007/BF01047682. S2CID 44831293.

- Husted, Thomas A.; Kenny, Lawrence W. (1997). "The Effect of the Expansion of the Voting Franchise on the Size of Government". Journal of Political Economy. 105 (1): 54–82. doi:10.1086/262065. S2CID 41897793.

- Krehbiel, Keith (2004). "Legislative Organization". Journal of Economic Perspectives. 18 (1): 113–128. doi:10.1257/089533004773563467. S2CID 249607866.

- McKelvey, Richard D. (1976). "Intransitives in Multidimensional Voting Models and Some Implications for Agenda Control". Journal of Economic Theory. 12 (3): 472–482. doi:10.1016/0022-0531(76)90040-5.

- Schummer, James; Vohra, Rakesh V. (2013). "Mechanism Design Without Money". In Nisan, Noam; Roughgarden, Tim; Tardos, Eva; Vazirani, Vijay (eds.). Algorithmic Game Theory. New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 246–252. ISBN 978-0-521-87282-9.

- Rice, Tom W. (1985). "An Examination of the Median Voter Hypothesis". Western Political Quarterly. 38 (2): 211–223. doi:10.2307/448625. JSTOR 448625.

- Romer, Thomas; Rosenthal, Howard (1979). "The Elusive Median Voter". Journal of Public Economics. 12 (2): 143–170. doi:10.1016/0047-2727(79)90010-0.

- Sobel, Russell S.; Holcombe, Randall G. (2001). "The Unanimous Voting Rule is not the Political Equivalent to Market Exchange". Public Choice. 106 (3–4): 233–242. doi:10.1023/A:1005298607876. S2CID 16736216.

- Waldfogel, Joel (2008). "The Median Voter and the Median Consumer: Local Private Goods and Population Composition". Journal of Urban Economics. 63 (2): 567–582. doi:10.1016/j.jue.2007.04.002. S2CID 152378898. SSRN 878059.