| Megaceroides algericus Temporal range: | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

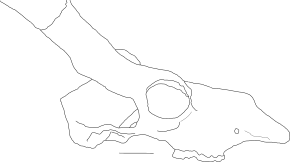

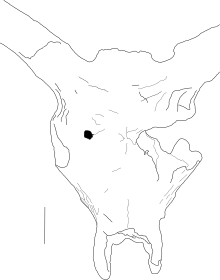

| Lateral view (top) and dorsal view (bottom) of an adult male skull of M. algericus from Aïn Bénian, Algeria, scale bars = 5 cm | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Family: | Cervidae |

| Subfamily: | Cervinae |

| Genus: | †Megaceroides Joleaud, 1914 |

| Species: | †M. algericus |

| Binomial name | |

| †Megaceroides algericus (Lydekker, 1890) | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Cervus pachygenys Pomel, 1892 | |

Megaceroides algericus is an extinct species of deer known from the Late Pleistocene to the Holocene of North Africa. It is one of only two species of deer known to have been native to the African continent, alongside the Barbary stag, a subspecies of red deer.[1] It is considered to be closely related to the giant deer species of Eurasia.

Taxonomy

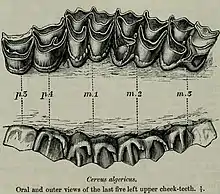

The species was first described by Richard Lydekker as Cervus algericus in 1890 from a maxilla with teeth found near Hammam Maskhoutine in Algeria.[2] The species Cervus pachygenys was erected for a pachyostotic mandible and an isolated molar found in Algeria by Auguste Pomel in 1892.[3] Léonce Joleaud in two publications in 1914 and 1916 synonymised the two species, and suggested affinities with the giant deer of Europe, and placed it in the newly erected subgenus Megaceroides within the genus Megaceros (junior synonym of Megaloceros) as the type species.[4][5] Camille Arambourg in publications in 1932 and 1938 raised Megaceroides to the full genus rank, and described additional cranial material, which were figured but not described in detail.[6][7]

_3_(15257223660).jpg.webp)

In 1953 Augusto Azzaroli published a systematic taxonomy for Megaloceros, he avoided using the name Megaceroides, and suggested affinities to his proposed "verticornis group" of Megaloceros species, and noted its similarities to Sinomegaceros pachyosteus. [8] The taxonomic relationships of giant deer and their smaller insular relatives (often referred to collectively as members of the tribe Megacerini, though it is not known whether the grouping is monophyletic) are unresolved, with a long and convoluted taxonomic history. The genus Megaceroides is also used as a synonym of Praemegaceros by some authors, reflecting to its unresolved taxonomic position with respect to other giant deer.[9] It was considered to belong to Megaloceros by Hadjouis in 1990 with Megaceroides at subgenus rank.[10] Affinities with Megaloceros have been suggested based on several morphological grounds. A comprehensive description of the taxon by Roman Croitor published in 2016 suggested that it originated from Megaloceros mugharensis from the Middle Pleistocene of the Levant, with Middle Pleistocene cervid remains from North Africa possibly belonging to an ancestor of the species, and retained Megaceroides at generic rank.[1] The craniodental morphology of Megaceroides algericus suggests its phylogenetic relationship with Eurasian giant deer Megaloceros giganteus. [11]

Distribution

The species was found within the Mediterranean region of northwest Africa north of the Atlas Mountains, with 26 known localities within Algeria and Morocco, extending from Bizmoune cave near Essaouira in the west to Hammam Maskhoutine and Puits des Chaachas in the East. The oldest known remains of the species are around 24,000 years Before Present.[1][12] No other deer are known to have been native to the African continent aside from M. algericus and the Barbary stag, an extant subspecies of red deer, which is also native to the same area of northwest Africa.[1]

Description

The species is known from limited material, and knowledge of post-cranial remains and antlers are poor. The estimated size of the animal is smaller than a red deer but slightly larger than a fallow deer. It is known from a mostly complete skull of an aged individual with worn teeth found near Aïn Bénian in Algeria, alongside other fragmentary crania.[1] The estimated body mass is approximately 100 kilograms (220 lb).[13]

The skull is broad, but the length of the skull, specifically the splanchnocranium (the region of the skull behind the dental region) is relatively short. This combination of a wide but proportionally short skull is a morphology that is unknown in any other deer species. The two halves of the mandible are estimated to have a contact angle of 60 degrees, which is extremely wide in comparison to other deer, to compensate for the wide skull. The parietals are flat, with a straight facial profile. The eyes face further outward and less forward than Sinomegaceros pachyosteus. The skull and dentary exhibit extreme thickening (pachyostosis) somewhat similar to that in Megaloceros, unlike Megaloceros, the vomer is largely unaffected. The pachyostosis is among the most extreme of any known mammal. The upper canines are absent (there are no sockets for them present on the Aïn Bénian skull) and the lower fourth premolar (P4) is molarised. The preserved proximal portion of the antler is straight and cylindrical in cross section, and orientated anteriorly, laterally and slightly dorsally, the antler becomes flattened distally.[1]

An isolated radius suggested to belong to the taxon is known from Berrouaghia, which is robust and proportionally short in comparison to other cervids, and the mid shaft measurement of 40mm is proportionally wider than that of M. giganteus.[1] Croitor suggests that several rock art drawings from the Altas and the Sahara depict the taxon, which show horned animals, some with antler like tines including proportionally long tails.[1] This interpretation, which had previously been suggested by other authors, has been criticised, noting that there are no known remains for the taxon from the Sahara, and that previous interpretations of the rock art representing deer had been based on faulty fossil identification of deer in Mali.[14]

Ecology

The ecology of the species is unclear owing to the lack of living analogues for its unique morphology. On several morphological grounds, Croitor proposed that its habits were peri- or semiaquatic, with the weak mastication ability and polished cheek teeth by attrition suggesting a preference for soft water plants, with taking of non-aquatic forage during the dry seasons. The extreme pachyostosis was suggested to have been a protection against attacks by crocodiles.[1]

Extinction

Remains from the Tamar Hat and Taza I archaeological sites suggests that the species may have been hunted by people.[15] The latest known date for the species from Bizmoune has an age estimated between 6641 and 6009 cal BP (4691 to 4059 BCE) at the end of the Epipaleolithic. The Holocene transition in North Africa also saw other extinctions of ungulates, including Gazella, Equus, Camelus, the African subspecies of the aurochs and Syncerus antiquus.[12]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Croitor, Roman (July–September 2016). "Systematical position and paleoecology of the endemic deer Megaceroides algericus Lydekker, 1890 (Cervidae, Mammalia) from the late Pleistocene-early Holocene of North Africa". Geobios. 49 (4): 265–283. Bibcode:2016Geobi..49..265C. doi:10.1016/j.geobios.2016.05.002.

- ↑ Lydekker, R., 1890. On a cervine jaw from Algeria. Proceedings of Zoological Society 1890, 602‐604.

- ↑ Pomel, A., 1892. Sur deux Ruminants de l’époque néolithique en Algérie: Cervus pachygenys et Antilope maupasi. Compte Rendu de l’Académie des Sciences 115, 213-216.

- ↑ Joleaud, L., 1914.Sur le Cervus (Megaceroides) algericus Lydekker, 1890. Comptes rendus des séances de la Société de biologie et deses filiales76, 737-739.

- ↑ Joleaud, L. 1916. Cervus (Megaceroides) algericus Lydekker, 1890. Recueil des Notices et Mémoires de la Société Archéologique du Département de Constantine 49 (6e volume de la cinquème série), 1-67

- ↑ Arambourg, C.,1932. Note préliminaire sur unenouvelle grotte à ossementsdes environs d’Alger.Bulletin de la Société d’Histoire Naturelle de l’Afrique du Nord 23,154-162.

- ↑ Arambourg, C.,1938. Mammifères fossiles du Maroc.Mémoires de la Société de Sciences Naturelles du Maroc 46,1-74.

- ↑ Azzaroli, A., 1953. The Deer of the Weybourn Crag and Forest Bed of Norfolk. Bulletin of the British Museum (Natural History), Geology 2,3-96.

- ↑ van der Made, Jan (June 2019). "The dwarfed "giant deer" Megaloceros matritensis n.sp. from the Middle Pleistocene of Madrid - A descendant of M. savini and contemporary to M. giganteus". Quaternary International. 520: 110–139. Bibcode:2019QuInt.520..110V. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2018.06.006. S2CID 133792579.

- ↑ Hadjouis, Djillali (1990). "Megaceroides algericus (Lydekker, 1890), du gisement des Phacochères (Alger, Algérie). Etude critique de la position systématique de Megaceroides". Quaternaire. 1 (3): 247–258. doi:10.3406/quate.1990.1941. ISSN 1142-2904.

- ↑ Croitor, R. 2021. Taxonomy, Systematics and Evolution of Giant Deer Megaloceros giganteus (Blumenbach, 1799) (Cervidae, Mammalia) from the Pleistocene of Eurasia. Quaternary, 4: 36, https://doi.org/10.3390/quat4040036

- 1 2 Fernandez, Philippe; Bouzouggar, Abdeljalil; Collina-Girard, Jacques; Coulon, Mathieu (July 2015). "The last occurrence of Megaceroides algericus Lyddekker, 1890 (Mammalia, Cervidae) during the middle Holocene in the cave of Bizmoune (Morocco, Essaouira region)". Quaternary International. 374: 154–167. Bibcode:2015QuInt.374..154F. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2015.03.034.

- ↑ Croitor, Roman (2022-11-06). "Paleobiogeography of Crown Deer". Earth. 3 (4): 1138–1160. Bibcode:2022Earth...3.1138C. doi:10.3390/earth3040066. ISSN 2673-4834.

- ↑ Camps, G. (1993-02-01). "Cerf . (Cervus elaphus barbarus)". Encyclopédie berbère (in French) (12): 1844–1853. doi:10.4000/encyclopedieberbere.2092. ISSN 1015-7344.

- ↑ Merzoug, Souhila (2012-06-01). "Essai d'interprétation du statut économique du Megaceroides algericus durant l'Ibéromaurusien dans le massif des Babors (Algérie)". Quaternaire (vol.23/2): 3. doi:10.4000/quaternaire.6183. ISSN 1142-2904. S2CID 127532579.