| Mexico City Metropolitan Cathedral | |

|---|---|

| Metropolitan Cathedral of the Assumption of the Most Blessed Virgin Mary into Heaven | |

Mexico City Metropolitan Cathedral and the Metropolitan Tabernacle, pictured in 2009 | |

| 19°26′04″N 99°07′59″W / 19.43439420°N 99.13308240°W | |

| Location | Mexico City, Mexico |

| Denomination | Catholic |

| Tradition | Roman Rite |

| Website | catedralmetropolitana |

| History | |

| Status | Cathedral |

| Dedication | Assumption of Mary |

| Consecrated | 2 February 1656[1] |

| Architecture | |

| Architect(s) | Claudio de Arciniega Juan Gómez de Trasmonte José Eduardo de Herrera José Damián Ortiz de Castro Manuel Tolsá |

| Style | Gothic, Plateresque, Baroque, Neoclassical |

| Groundbreaking | 1573 |

| Completed | 1813 |

| Specifications | |

| Length | 128 metres (420 ft) |

| Width | 59 metres (194 ft) |

| Height | 67 metres (220 ft) |

| Materials | Chiluca, stone, tezontle |

| Administration | |

| Archdiocese | Mexico |

| Clergy | |

| Archbishop | Cardinal Carlos Aguiar Retes |

The Metropolitan Cathedral of the Assumption of the Most Blessed Virgin Mary into Heaven (Spanish: Catedral Metropolitana de la Asunción de la Bienaventurada Virgen María a los cielos) is the cathedral church of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Mexico.[2] It is situated on top of the former Aztec sacred precinct near the Templo Mayor on the northern side of the Plaza de la Constitución (Zócalo) in the historic center of Mexico City. The cathedral was built in sections from 1573 to 1813[3] around the original church that was constructed soon after the Spanish conquest of Tenochtitlan, eventually replacing it entirely. Spanish architect Claudio de Arciniega planned the construction, drawing inspiration from Gothic cathedrals in Spain.[4]

Due to the long time it took to build it, just under 250 years, virtually all the main architects, painters, sculptors, gilding masters and other plastic artists of the viceroyalty worked at some point in the construction of the enclosure. The long construction time also led to the integration of a number of architectural styles in its design, including the Gothic, Baroque, Churrigueresque, Neoclassical styles, as they came into vogue over the centuries. It furthermore allowed the cathedral to include different ornaments, paintings, sculptures and furniture in its interior.[5][6][3] The project was a point of social cohesion, because it involved so many generations and social classes, including ecclesiastical authorities, government authorities, and different religious orders.[7]

The influence of the Catholic Church on public life has meant that the building was often the scene of historically significant events in New Spain and independent Mexico. These include the coronations of Agustin I and his wife Ana María Huarte in 1822 by the President of the Congress, and Maximilian I and Empress Carlota of Mexico as emperors of Mexico by the Assembly of Mexican notables;[8][9][10][11] the preservation of the funeral remains of the aforementioned first emperor; burial, until 1925, of several of the independence heroes, such as Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla and José María Morelos; the disputes between liberals and conservatives caused by the separation of the church and the state in the Reform; the closure of the building in the days of the Cristero War; and the celebrations of the bicentennial of independence, among others.[12]

The cathedral faces south. It is approximately 59 metres (194 ft) wide by 128 metres (420 ft) long, with a height of 67 metres (220 ft) to the tip of the towers. It consists of two bell towers, a central dome, and three main portals. It has four façades which contain portals flanked with columns and statues. It has five naves consisting of 51 vaults, 74 arches and 40 columns. The two bell towers contain 25 bells. The tabernacle, adjacent to the cathedral, contains the baptistery and serves to register the parishioners. There are five large, ornate altars, a sacristy, a choir, a choir area, a corridor and a capitulary room. Fourteen of the cathedral's sixteen chapels are open to the public. Each chapel is dedicated to a different saint or saints, and each was sponsored by a religious guild. The chapels contain ornate altars, altarpieces, retablos, paintings, furniture and sculptures. The cathedral is home to two of the largest 18th-century organs in the Americas. There is a crypt underneath the cathedral that holds the remains of many former archbishops. The cathedral has approximately 150 windows.[3]

Over the centuries, the cathedral has suffered damage. A fire in 1967 damaged a significant part of the cathedral's interior. The restoration work that followed uncovered a number of important documents and artwork that had previously been hidden. Although a solid foundation was built for the cathedral,[13] the soft clay soil it is built on has been a threat to its structural integrity. Dropping water tables and accelerated sinking caused the structure to be added to the World Monuments Fund list of the 100 Most Endangered Sites. Restoration working beginning in the 1990s stabilized the cathedral and it was removed from the endangered list in 2000.[14]

History

Background: The Major Church

After the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire, and after Hernán Cortés returned from exploring what is today Honduras, the conquistadors decided to build a church on the site of the Templo Mayor of the Aztec City of Tenochtitlan in order to consolidate Spanish power over the newly conquered territory. There is evidence of the existence of a great major temple dedicated to the god Quetzalcoatl, a temple dedicated to the god Huītzilōpōchtli,[15] a temple dedicated to Tonatiuh, and other minor buildings. The architect Martín de Sepúlveda was the first director of the project between 1524 and 1532, while Juan de Zumárraga was the first bishop of the episcopal see in the New World. The cathedral of Zumárraga was located in the northeastern part of what is now the cathedral. It had three naves separated by Tuscan columns, the central ceiling had intricate engravings made by Juan Salcedo Espinosa and gilded by Francisco de Zumaya and Andrés de la Concha. The main door was probably Renaissance style. The choir had 48 ceremonial chairs made by hand by Adrián Suster and Juan Montaño in pinus ayacahuite wood. For the construction, they used the stones of the destroyed temple of the god Huītzilōpōchtli, god of war and principal deity of the Aztecs.[14][3] In spite of everything, this temple was soon considered insufficient for the growing importance of the capital of the Viceroyalty of New Spain. This first church was elevated to a cathedral by King Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor and Pope Clement VII according to the bull of 9 September 1534[16] and, later, named Metropolitan by Pope Paul III in 1547.[17]

This small, poor church, vilified by all the chroniclers who judged it unworthy of such famous new city, rendered its services well that badly for long years. Soon it was ordered that a new temple be erected, proportionate sumptuousness to the greatness of the colony more, but this new factory encountered so many obstacles for its beginning, with so many difficulties for its continuation, that the old cathedral saw passing in its narrow sumptuous ceremonies of the viceroyalty; and only when the fact that motivated them was of great importance would he prefer another church, like that of San Francisco, to raise in its huge chapel of San José de los Indios the burial mound for the funeral ceremonies of Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor.

Seeing that the conclusion of the new church was long, its factory was already beginning, in 1584 it was decided to completely repair the Old Cathedral, which would certainly be little less than ruinous, to celebrate in it the Third Mexican Provincial Council.[18]

The church was a little longer than the front of the new cathedral; its three naves were not 30 meters wide and were covered, the central one with a step-scissors armour, those on the sides with horizontal beams. In addition to the puerta del Perdón door had another call puerta de los Canónigos door, and perhaps a third was left to the Placeta del Marqués.[19] Years later, the cathedral was small for its function. In 1544, the ecclesiastical authorities had already ordered the construction of a new and more sumptuous cathedral.

View of the Jaén Cathedral.

View of the Jaén Cathedral.%252C_Catedral._Proyecto_ideal_de_Juan_de_Herrera%252C_seg%C3%BAn_Chueca-Goitia..JPG.webp) Project of the Valladolid Cathedral.

Project of the Valladolid Cathedral.

Start of the work

Almost all the American cathedrals of this first Renaissance period follow the model of that of Jaén, whose first stone was laid in 1540. With a rectangular plan and, at most with the main chapel octagonal, are the cathedrals of Mexico City, Puebla ... (...) It was mainly inspired by the Cathedral of Jaén in 1540, with a rectangular plan and a flat chevet, although it is probable that it was also seduced by the Herrerian model of that of Valladolid, the relationship of the Valladolid Cathedral, projected in 1580, with the [Hispanic] American cathedrals has not been sufficiently taken into account.

— Extracted from El Arte Hispanoamericano (1988).[20]

In 1552, an agreement was reached whereby the cost of the new cathedral would be shared by the Spanish Crown, the Comendadores and the Indians under the direct authority of the Archbishop of New Spain.[14] The initial plans for the foundation of the new cathedral began in 1562, as part of the project for the construction of the work, then archbishop Alonso de Montúfar would have proposed a monumental construction composed of seven naves and based on the design of the Seville Cathedral; a project that, according to Montúfar himself, would take 10 or 12 years. The weight of a work of such dimensions in a subsoil of swampy origin would require a special foundation. Initially, cross beams were placed to build a platform, which required high costs and constant draining, in the end this project would be abandoned not only for the aforementioned cost, but for the floods suffered by the city center. It is then that, supported by indigenous techniques, solid wooden logs are injected at great depth, about twenty thousand of these logs in an area of six thousand square meters. The project is reduced from the original seven naves to only five: one central, two processional and two lateral for the 16 chapels. The construction began with the designs and models created by Claudio de Arciniega and Juan Miguel de Agüero, inspired by the Spanish cathedrals of Jaén and Valladolid.[4]

In 1571, with some delay, the viceroy Martín Enríquez de Almanza and the archbishop Pedro Moya de Contreras placed the first stone of the present church. The cathedral began to be built in 1573 around the existing church which was demolished when the works advanced sufficiently to house the basic functions of the church.

The work began with a north–south orientation, contrary to that of most cathedrals, due to the waterfalls of the subsoil that would affect the building with a traditional east–west orientation, decision taken 1570.[13] First the chapter house and the sacristy were built; the construction of the vaults and the naves took a hundred years.

Construction development

The beginning of the works was met with a muddy and unstable terrain that complicated the works, because of this, the Tezontle and the Chiluca Stone were favored as building materials in several areas, on the quarry, as these are lighter. In 1581, the walls began to be erected[13] and in 1585 the works began in the first chapel, at that time the names of the stonemasons who worked on the work were: in the chapels were carved by Juan Arteaga and the niches Hernán García de Villaverde, who also worked on the Toral pillars whose mediums were sculpted by Martín Casillas. In 1615, the walls reached half its total height.[13] The works of the interior began in 1623 by the sacristy,[21] and the early church was demolished at its conclusion. What is now the vestry was where Mass was conducted after the first church was finally torn down.[22] On the 21st September 1629, the works were interrupted by the flood suffered by the city,[13] in which the water reached two meters in height, causing damage in the main square,[13] today called Plaza del Zócalo, and other parts of the city. Due to the damage, a project was started to build the new cathedral in the Tacubaya hills,[13] west of the city but the idea was discarded, and the project continued at the same location, under the direction of Juan Gómez de Trasmonte, the interior was finished and consecrated in 1667.[21]

The archbishop Marcos Ramírez de Prado y Ovando made the second dedication on 22 December 1667, the year in which the last vault was closed. The date of consecration, (lacking, at that time, of bell towers, main façade and other elements built in the 18th century), the cost of construction was equivalent to 1 759 000 pesos. This cost was covered in good part by the Spanish kings Philip II, Philip III, Philip IV and Charles II.[17] Annexes to the central core of the building would be added over the years the Seminary College, the Chapel of the Animas, and the buildings of the Tabernacle and the Curia.

In 1675, the central part of the main façade was completed, the work of the architect Cristóbal de Medina Vargas, which included the figure of the Assumption of Mary, the title to which the cathedral is dedicated, and the sculptures of James the Great and Andrew the Apostle guarding it. During the remainder of the 17th century, the first body of the east tower was built, by the architects Juan Lozano and Juan Serrano. The main portal of the building and portals on the east side were built in 1688 and that of the west in 1689. The six buttresses that support the structure on the side of its main facade and the bottoms that support the vaults of the main nave were completed.[23]

During the 18th century little was done to advance in the completion of the construction of the cathedral; largely because, now completed in its interior, and handy for all the ceremonies that were offered, there had not the urgent need to continue working on what was missing.

Although the work had in fact been suspended, some works in the interior continued; by 1737 it was the master builder Domingo de Arrieta. He made, in the company of José Eduardo de Herrera, master of architecture, the stands that surround the choir. In 1742 Manuel de Álvarez, master of architecture, ruled with Herrera himself about the presbytery project presented by Jerónimo de Balbás.

In 1752, on 17 September, a cross of iron, with more than three varas, with its vane, was placed on the crown of the lantern tower of this church, engraved on one side and on the other side the prayer of the Sanctus Deus, and in the middle of it a fourth-by-fourth oval, in which a wax of Agnus was placed on one side with its window and on the other side a sheet in which Saint Prisca, lawyer of the rays, was sculpted. The ear of the cross is of two varas, and all its weight is of fourteen arrobas; it is nailed to a quarry base.[24]

In 1787, the architect José Damián Ortiz de Castro was appointed, after a competition in which it imposed the projects of José Joaquín García de Torres and Isidro Vicente de Balbás, to direct the construction works of the bell towers, the main facade and the dome. For the construction of the towers, the Mexican architect Ortiz de Castro designed a project to make them effective against earthquakes; a second body that looks piercing and a bell-shaped finishing. His direction in the project continued until his death in 1793. When he was replaced by Manuel Tolsá, architect and sculptor driver of the Neoclassical, who arrived in the country in 1791. Tolsá is in charge of completing the work of the cathedral. He reconstructs the dome that was low and disproportionate, designs a project that consists of opening a larger ring on which builds a circular platform, to lift from there a much higher roof lantern. Integrates the torches, statues and balustrades. He crown the facade with figures symbolizing the three theological virtues (faith, hope and charity).[25][26][13]

- Historical photographs of the cathedral.

View of the Plaza Mayor de México, 1797 by Rafael Ximeno y Planes

View of the Plaza Mayor de México, 1797 by Rafael Ximeno y Planes Plaza Mayor de México (today Plaza del Zócalo), 1830 by Theubet de Beauchamp

Plaza Mayor de México (today Plaza del Zócalo), 1830 by Theubet de Beauchamp General Scott's entrance into Mexico, 1847 by Carl Nebel

General Scott's entrance into Mexico, 1847 by Carl Nebel The Cathedral of Mexico City, 1850 by Pietro Gualdi

The Cathedral of Mexico City, 1850 by Pietro Gualdi.jpg.webp) A trip to Mexico, 1880 by Henry C. R. Becher

A trip to Mexico, 1880 by Henry C. R. Becher View of the cathedral between 1880 and 1887, when the Aztec sun stone was moved to the Museo de la Calle de Moneda

View of the cathedral between 1880 and 1887, when the Aztec sun stone was moved to the Museo de la Calle de Moneda.jpg.webp) Interior of the Cathedral of Mexico City, 1850 by Pierre Frédéric Lehnert

Interior of the Cathedral of Mexico City, 1850 by Pierre Frédéric Lehnert Interior of the Cathedral, 1884 by Frederick A. Ober

Interior of the Cathedral, 1884 by Frederick A. Ober.jpg.webp) Rear altar at the interior, 1905, California Historical Society Collection

Rear altar at the interior, 1905, California Historical Society Collection.jpg.webp) Interior of the Cathedral, 1905, California Historical Society Collection

Interior of the Cathedral, 1905, California Historical Society Collection

Exterior

Facades and portals

The main facade of the cathedral faces south. The main portal is centered in the main facade and is the highest of the cathedral's three portals. Statues of Saint Peter and Paul the Apostle stand between the columns of the portal, while Saint Andrew and James the Just are depicted on the secondary doorway. In the center of this doorway is a high relief of the Assumption of the Virgin Mary, to whom the cathedral is dedicated.[3] This image is flanked by images of Saint Matthew and Saint Andrew. The coat of arms of Mexico is above the doorway, with the eagle's wings outstretched. There is a clock tower at the very top of the portal with statues representing Faith, Hope and Charity, which was created by sculptor Manuel Tolsá.[13]

The west facade was constructed in 1688 and rebuilt in 1804. It has a three-section portal with images of the Four Evangelists.[13] The west portal has high reliefs depicting Jesus handing the Keys of Heaven to Saint Peter.

The east facade is similar to the west facade. The reliefs on the east portal show a ship carrying the four apostles, with Saint Peter at the helm.[3] The title of this relief is The ship of the Church sailing the seas of Eternity.[13]

The northern facade, built during the 16th century in the Renaissance Herrera style, is oldest part of the cathedral and was named after Juan de Herrera, architect of the El Escorial monastery in Spain.[3] While the eastern and western facades are older than most of the rest of the building, their third level has Solomonic columns which are associated with the Baroque period.

All the high reliefs of the portals of the cathedral were inspired by the work of Flemish painter Peter Paul Rubens.[3]

Bell towers

The bell towers are the work of Xalapan artist José Damián Ortiz de Castro. They are capped with bell-shaped roofs made of tezontle covered in chiluca, a white stone. Ortiz de Castro was in charge of the cathedral's construction in the latter half of the 18th century until he died, unexpectedly. Manuel Tolsá of Valencia, who had built other notable buildings in Mexico City, was hired to finish the cathedral. At this point, the cathedral had already been 240 years in the making. He added the neo-Classic structure housing the clock, the statues of the three theological virtues (Faith, Hope, and Charity), the high balustrade surrounding the building, and the dome that rises over the transept.

The cathedral has 25 bells—eighteen hang in the east bell tower and seven in the west tower. The largest bell is named the Santa Maria de Guadalupe and weighs around 13,000 kilograms (29,000 lb). Other major bells are named the Doña Maria, which weighs 6,900 kilograms (15,200 lb), and La Ronca ("the hoarse one"), named so because of its harsh tone. Doña Maria and La Ronca were placed in 1653 while the largest bell was placed later in 1793.[3]

The statues in the west tower are the work of José Zacarías Cora and represent Pope Gregory VII, Saint Augustine, Leander of Seville, St. Fulgentius of Écija, St.Francis Xavier, and Saint Barbara. The statues in the east tower are by Santiago Cristóbal Sandoval and depict Emilio, Rose of Lima, Mary (mother of Jesus), Ambrogio, Jerome, Philip of Jesus, Hippolytus of Rome, and Isidore the Laborer.[13]

In 1947, a novice bell ringer died in an accident when he tried to move one of the bells while standing under it. The bell swung back and hit him in the head, killing him instantly. The bell was then "punished" by removing the clapper. In the following years, the bell was known as la castigada ("the punished one"), or la muda ("the mute one"). In 2000, the clapper was reinstalled in the bell.[27]

In October 2007, a time capsule was found inside the stone ball base of a cross, in the southern bell tower of the cathedral. It was placed in 1742, supposedly to protect the building from harm. The lead box was filled with religious artifacts, coins and parchments and hidden in a hollow stone ball. The ball was marked with the date of 14 May 1791, when the building's topmost stone was laid. A new time capsule will be placed in the stone ball when it is closed again.[28]

Tabernacle

Situated to the right of the main cathedral, the Metropolitan Tabernacle (Spanish: Sagrario Metropolitano) was built by Lorenzo Rodríguez during the height of the Baroque period between 1749 and 1760,[3] to house the archives and vestments of the archbishop.[29] It also functioned and continues to function as a place to receive Eucharist and register parishioners.[30]

The first church built on the cathedral site also had a tabernacle, but its exact location is unknown. During the construction of the cathedral, the tabernacle was housed in what are now the Chapels of San Isidro and Our Lady of Agony of Granada. However, in the 18th century, it was decided to build a structure that was separate, but still connected, to the main cathedral.[30] It is constructed of tezontle (a reddish porous volcanic rock) and white stone in the shape of a Greek cross with its southern facade faces the Zócalo. It is connected to the main cathedral via the Chapel of San Isidro.[13][3]

The interiors of each wing have separate uses. In the west wing is the baptistry, in the north is the main altar, the main entrance and a notary area, separated by inside corner walls made of chiluca stone and tezontle. Chiluca, a white stone, covers the walls and floors and the tezontle frames the doors and windows. At the crossing of the structure is an octagonal dome framed by arches that form curved triangles where they meet at the top of the dome.[30] The principal altar is in the ornate Churrigueresque style and crafted by indigenous artist Pedro Patiño Ixtolinque. It was inaugurated in 1829.[13]

The exterior of the Baroque styled tabernacle is almost entirely adorned with decorations, such as curiously shaped niche shelves, floating drapes and many cherubs. Carvings of fruits such as grapes and pomegranates have been created to in the shape of ritual offerings, symbolizing the Blood of Christ and the Church. Among the floral elements, roses, daisies, and various types of four-petalled flowers can be found, including the indigenous chalchihuite.[3]

The tabernacle has two main outside entrances; one to the south, facing the Zócalo and the other facing east toward Seminario Street. The southern façade is more richly decorated than the east façade. It has a theme of glorifying the Eucharist with images of the Apostles, Church Fathers, saints who founded religious orders, martyrs as well as scenes from the Bible. Zoomorphic reliefs can be found along with the anthropologic reliefs, including a rampaging lion, and the eagle from the coat of arms of Mexico. The east facade is less ambitious but contains figures from the Old Testament as well as the images of John Nepomucene and Ignacio de Loyola. Construction dates for the phases of the tabernacle are also inscribed here.[30]

Interior

Altars

High Altar

This disappeared in the 1940s. In 2000, a new altar table was made to replace the previous one. This was built in modernist style by the architect Ernesto Gómez Gallardo.

Altar of Forgiveness

The Altar of Forgiveness (Spanish: Altar del perdón) is located at the front of the central nave. It is the first aspect of the interior that is seen upon entering the cathedral. It was the work of Spanish architect Jerónimo de Balbás, and represents the first use of the estípite column (an inverted triangle-shaped pilaster) in the Americas.[3]

There are two stories about how the name of this altar came about. The first states that those condemned by the Spanish Inquisition were brought to the altar to ask for forgiveness in the next world before their execution. The second relates to painter Simon Pereyns, who despite being the author of many of the works of the cathedral, was accused of blasphemy. According to the story, while Pereyns was in jail, he painted such a beautiful image of the Virgin Mary that his crime was forgiven.[31]

This altar was slightly damaged by fire in January 1967, and it was restored.[3]

Altar of the Kings

In New Spain, it was customary to dedicate the main chapel of any Spanish cathedral to the ruling king, giving it the greatest importance and artistic wealth. The Altar of the Kings (Spanish: Altar de los Reyes) was also the work of Jerónimo de Balbás, in Mexican Baroque or Churrigueresque style.[3] Balbás constructed it in cedar from 1718 to 1725.[29][32] It was gilded and finished by Francico Martínez in 1736 and completed in 1737.[13] It is located at the back of the cathedral, beyond the Altar of Forgiveness and the choir, a space known as "royal chapel", although it does not have any grille that delimits and closes the space in the manner of similar chapels. This altar is 13.75 metres (45.1 ft) wide, 25 metres (82 ft) tall and 7.5 metres (25 ft) deep, so it presides over the main nave of the temple because it is located behind the presbytery.[33] There are three main vertical bodies formed by high estipite pilasters. Its size and depth gave rise to the nickname la cueva dorada ("the golden cave").

Additional sculptures were created by Sebastián de Santiago.[34] It takes its name from the statues of saintly royalty which form part of its decoration,[3] and is the oldest work in churrigueresque style in Mexico, taking 19 years to complete. At the bottom, from left to right, are six female royal saints: Saint Margaret of Scotland, Helena of Constantinople, Elisabeth of Hungary, Elizabeth of Aragon, Empress Cunegunda and Edith of Wilton.[35] In the middle of the altar are six canonized kings: Hermenegild, a Visigoth martyr; Henry II, Holy Roman Emperor; Edward the Confessor; and Casimir of Poland below, and Saints Louis of France and Ferdinand III of Castile above them. In between these kings an oil painting of the Adoration of the Magi by Juan Rodriguez Juarez shows Jesus as the King of kings. The top portion features a painting of the Assumption of Mary as celestial queen flanked by oval bas reliefs, one of Saint Joseph carrying the infant Jesus and the other of Saint Teresa of Ávila with a quill in her hand and the Holy Spirit above her, inspiring her to write.[36] In the upper part above this, there are angels carrying the attributes of the Virgin Mary such as the Sealed Fountain, the House of Gold, the Well of Living Water, and the Tower of David, and at the top is an image of God, the Father.[31]

The altar was damaged due to a fire in 1967.[37] This altar has been under restoration since 2003.[22]

Sacristy

The Herrera door opens into the sacristy, the oldest part of the cathedral. It is a mixture of Renaissance and Gothic styles.

The walls hold large canvases painted by Cristóbal de Villalpando, such as The Apotheosis of Saint Michael, The Triumph of the Eucharist, The Church Militant and the Church Triumphant, and The Virgin of the Apocalypse.[3] The Virgin of the Apocalypse depicts the vision of John of Patmos.[38] Two other canvases, Entering Jerusalem and The Assumption of the Virgin, painted by Juan Correa, are also here.[3] An additional painting, attributed to Bartolomé Esteban Murillo, hangs in the Sacristy.

On the north wall, there is a niche that holds a statue of the crucifix with a Christ image sculpted in ivory. Behind this, is another mural that depicts the Juan Diego's of Our Lady of Guadalupe. The Sacristy used to house Juan Diego's cloak, upon which the Virgin's image purportedly appears, but after massive flooding in 1629, it was removed from the Sacristy to better protect it.[38]

A cabinet on the west wall of the Sacristy, under the Virgin of the Apocalypse painting, once held golden chalices and cups trimmed with precious stones, as well as other utensils.

In 1957, The wooden floor and platform around the perimeter of the Sacristy were replaced with stone.

Chapels

The cathedral's sixteen chapels were each assigned to a religious guild, and each is dedicated to a saint. Each of the two side naves contain seven chapels. The other two were created later on the eastern and western sides of the cathedral. These last two are not open to the public.[3] The fourteen chapels in the east and west naves are listed below. The first seven are in the east nave, listed from north to south, and the last seven are in the west nave.

Chapel of Our Lady of the Agonies of Granada

The Chapel of Our Lady of the Agonies of Granada (Spanish: Capilla de Nuestra Señora de las Angustias de Granada) was built in the first half of the 17th century and originally served as the sacristy. It is a medieval-style chapel with a ribbed vault and two relatively simple altarpieces. The narrow altarpiece contains an oval painting of Saint Raphael, Archangel and the young Tobias, a 16th century painting attributed to Flemish painter Maerten de Vos. At the top of this altarpiece is a painting of Our Lady of Mount Carmel, and above this is a painting of the Last Supper. At the back of the chapel is a churrigueresque painting of Our Lady of the Agonies of Granada.

Chapel of Saint Isidore

The Chapel of Saint Isidore (Spanish: Capilla de San Isidro) was originally built as an annex between 1624 and 1627 and was once used as the baptistery. Its vault contains plaster casts representing Faith, Hope, Charity, and Justice, considered to be basic values in the Catholic religion. After the Tabernacle was built, it was converted into a chapel and its door was reworked in a churrigueresque style.

Chapel of the Immaculate Conception

.jpg.webp)

The Chapel of the Immaculate Conception (Spanish: Capilla de la Inmaculada Concepción) was built between 1642 and 1648. It has a churrigueresque altarpiece which, due to the lack of columns, most likely dates from the 18th century. The altar is framed with molding—instead of columns—and a painting of the Immaculate Conception presides over it. The altar is surrounded by paintings by José de Ibarra relating to the Passion of Christ and various saints. The chapel also contains a canvas of Saint Christopher painted by Simon Pereyns in 1588, and the Flagellation by Baltasar de Echave Orio, painted in 1618. The altarpiece on the right side[39] is also dedicated to the Immaculate Conception and was donated by the College of Saints Peter and Paul. This chapel holds the remains of Franciscan friar Antonio Margil de Jesús who was evangelized in what is now the north of Mexico.

Chapel of Our Lady of Guadalupe

The Chapel of Our Lady of Guadalupe (Spanish: Capilla de Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe) was built in 1660. It was the first baptistery of the cathedral and for a long time was the site for the Brotherhood of the Most Holy Sacrament, which had many powerful benefactors. It is decorated in a 19th century neo-classic style by the architect Antonio Gonzalez Vazquez, director of the Academy of San Carlos. The main altarpiece is dedicated to the Virgin of Guadalupe and the sides altars are dedicated to John the Baptist and San Luis Gonzaga.

Chapel of Our Lady of Antigua

The Chapel of Our Lady of Antigua (Spanish: Capilla de Nuestra Señora de La Antigua) was sponsored and built between 1653 and 1660 by a brotherhood of musicians and organists, which promoted devotion to this Virgin. Its altarpiece contains a painting of the Virgin, a copy of one found in the Cathedral of Seville. This copy was brought to New Spain by a merchant. Two other paintings show the birth of the Virgin and her presentation. Both were painted by Nicolás Rodriguez Juárez.

This chapel is home to the Niño Cautivo (Captive Child) a Child Jesus figure that was brought to Mexico from Spain. It was sculpted in the 16th century by Juan Martínez Montañés in Spain and purchased by the cathedral. However, on its way to Veracruz, pirates attacked the ship it was on and sacked it. To get the image back, a large ransom was paid. Today, the image is in the Chapel of San Pedro or De las Reliquias.[40] Traditionally, the image has been petitioned by those seeking release from restrictions or traps, especially financial problems or drug addiction or alcoholism.[41] The cult to the Niño Cautivo is considered to be "inactive" by INAH.[42] However, this particular image has made a comeback since 2000 as one to petition when a family member is abducted and held for ransom.[41]

Chapel of Saint Peter

.jpg.webp)

The Chapel of Saint Peter (Spanish: Capilla de San Pedro) was built between 1615 and 1620 and contains three highly decorated Baroque altarpieces from the 17th century. The altar at the back is dedicated to Saint Peter, whose sculpture presides over the altar. It is surrounded by early 17th century paintings relating to his life, painted by Baltasar de Echave Orio. To the right is an altarpiece dedicated to the Holy Family, with two paintings by Juan Francisco de Aguilera called The Holy Family in the workshop of Saint Joseph and Birth of the Savior. The altarpiece to the left of the main altarpiece is dedicated to Saint Theresa of Jesus whose image also appears in the chapel's window. It includes four paintings on sheets of metal that depict scenes from the birth of Jesus. Five oil paintings illustrate scenes from the life of Saint Theresa, and above this is a semi-circular painting of the coronation of Mary. All these works were created in the 17th century by Baltasar de Echave y Rioja.[31]

Chapel of Christ and of the Reliquaries

.jpg.webp)

The Chapel of Christ and of the Reliquaries (Spanish: Capilla del Santo Cristo y de las Reliquias) was built in 1615 and designed with ultra-Baroque details which are often difficult to see in the poorly lit interior.[3] It was originally known as the Christ of the Conquistadors. That name came from an image of Christ that was supposedly donated to the cathedral by Emperor Charles V. Over time, so many reliquaries were left on its main altar that its name was eventually changed. Of 17th century ornamentation, the main altarpiece alternates between carvings of rich foliage and small heads on its columns in the main portion and small sculptures of angels on its telamons in the secondary portion. Its niches hold sculptures of saints framing the main body. Its crucifix is from the 17th century. The predella is finished with sculptures of angels, and also contains small 17th paintings of martyred saints by Juan de Herrera. Behind these paintings, hidden compartments contain some of the numerous reliquaries left here. Its main painting was done by José de Ibarra and dated 1737. Surrounding the altar is a series of paintings on canvas, depicting the Passion of Christ by José Villegas, painted in the 17th century. On the right-hand wall, an altar dedicated to the Virgin of the Confidence is decorated with numerous churrigueresque figurines tucked away in niches, columns and top pieces.[31]

Chapel of the Holy Angels and Archangels

.jpg.webp)

The Chapel of the Holy Angels and Archangels (Spanish: Capilla de los Ángeles) was finished in 1665 with Baroque altarpieces decorated with Solomonic columns. It is dedicated to the Archangel Michael, who is depicted as a medieval knight.[3] It contains a large main altarpiece with two smaller altarpieces both decorated by Juan Correa.[29] The main altarpiece is dedicated to the seven archangels, who are represented by sculptures, in niches surrounding images of Saint Joseph, Mary and Christ. Above this scene are the Holy Spirit and God the Father. The left-hand altarpiece is of similar design and is dedicated to the Guardian Angel, whose sculpture is surrounded with pictures arranged to show the angelic hierarchy. To the left of this, a scene shows Saint Peter being released from prison, and to the right, Saul, later Saint Paul, being knocked from his horse, painted by Juan Correa in 1714. The right-hand altarpiece is dedicated to the Guardian Angel of Mexico.[31]

Chapel of Saints Cosme and Damian

The Chapel of Saints Cosme and Damian (Spanish: Capilla de San Cosme y San Damián) was built because these two saints were commonly invoked during a time when New Spain suffered from the many diseases brought by the Conquistadors. The main altarpiece is Baroque, probably built in the 17th century. Oil paintings on wood contain scenes from physician saints and are attributed to painter Sebastián López Dávalos, during the second half of the 17th century. The chapel contains one small altarpiece which came from the Franciscan church in Zinacantepec, to the west of Mexico City, and is dedicated to the birth of Jesus.[31]

Chapel of Saint Joseph

The Chapel of Saint Joseph (Spanish: Capilla de San José), built between 1654 and 1660, contains an image of Our Lord of Cacao, an image of Christ most likely from the 16th century. Its name was inspired from a time when many indigenous worshipers would give their alms in the form of cocoa beans. Churrigueresque in style and containing a graffito statue of Saint Joseph, patron saint of New Spain,[3] the main altarpiece is Baroque and is from the 18th century. This once belonged to the Church of Our Lady of Monserrat. This altar contains statues and cubicles containing busts of the Apostles but contains no paintings.[31]

Chapel of Our Lady of Solitude

The Chapel of Our Lady of Solitude (Spanish: Capilla de Nuestra Señora de la Soledad) was originally built in honor of the workers who built the cathedral. It contains three Baroque altarpieces. The main altarpiece is supported by caryatids and small angels as telamons, to uphold the base of the main body. It is dedicated to the Virgin of Solitude of Oaxaca, whose image appears in the center. The surrounding 16th century paintings are by Pedro Ramírez and depict scenes from the life of Christ.[31]

Chapel of Saint Eligius

The Chapel of Saint Eligius (Spanish: Capilla de San Eligio), also known as the Chapel of the Lord of Safe Expeditions (Spanish: Capilla del Señor del Buen Despacho), was built by the first silversmith guild, who donated the images of the Conception and Saint Eligius to whom the chapel was formerly dedicated. The chapel was redecorated in the 19th century, and the image of Our Lord of Good Sending was placed here, named thus, since many supplicants reported having their prayers answered quickly. The image is thought to be from the 16th century and sent as a gift from Charles V of Spain.[31]

Chapel of Our Lady of Sorrows

The Chapel of Our Lady of Sorrows (Spanish: Capilla de Nuestra Señora de los Dolores), formerly known as the Chapel of the Lord's Supper (Spanish: Capilla de la Santa Cena), was built in 1615. It was originally dedicated to the Last Supper since a painting of this event was once kept here. It was later remodeled in a Neo-classical style, with three altarpieces added by Antonio Gonzalez Velazquez. The main altarpiece contains an image of the Virgin of Sorrows sculpted in wood and painted by Francisco Terrazas, at the request of Emperor Maximilian I of Mexico. On the left-hand wall a ladder leads to a series of crypts which hold most of the remains of past archbishops of Mexico. The largest and grandest of these crypts contains the remains of Juan de Zumárraga, the first archbishop of Mexico.[31]

Chapel of the Lord of Good dispatch

The Chapel of the Lord of Good dispatch (Spanish: Capilla del Señor del Buen Despacho) was premiered on December 8, 1648, and was dedicated to the silversmiths' guild, who placed two images of solid silver, one of the purest conception and another of San Eligio or Eloy.

The decoration of the entire chapel is neoclassical style belongs to the first half of the nineteenth century.

Chapel of Saint Philip of Jesus

The Chapel of Saint Philip of Jesus (Spanish: Capilla de San Felipe de Jesús) was completed during one of the earliest stages of the construction of the cathedral. It is dedicated to Philip of Jesus, a friar and the only martyr from New Spain, who was crucified in Japan. The chapel is topped with a Gothic-style dome and has a Baroque altarpiece from the 17th century. A statue of the saint is located in a large niche in the altarpiece. The altar to the left is dedicated to Saint Rose of Lima, considered a protector of Mexico City. To the right is an urn which holds the remains of Agustín de Iturbide, who briefly ruled Mexico from 1822 to 1823.[3][31] Next to this chapel is a baptismal font, in which it is believed Philip of Jesus was baptised.[31] The heart of Anastasio Bustamante is preserved here. In this chapel is a sculpture alluding to the first Mexican saint: San Felipe de Jesús. This work, as seen by many art critics, is the best elaborated, carved and polychrome sculptured sculpture from Latin America.

Organs

The cathedral has had perhaps a dozen organs over the course of its history.[43] The earliest is mentioned in a report written to the king of Spain in 1530. Few details survive of the earliest organs. Builders names begin to appear at the end of the sixteenth century. The earliest disposition that survives is for the Diego de Sebaldos organ built in 1655.[44] The first large organ for Mexico City Cathedral was built in Madrid from 1689 to 1690 by Jorge de Sesma and installed by Tiburcio Sanz from 1693 to 1695.[45] It now has two, which were made in Mexico by José Nassarre of Spain, and completed by 1736, incorporating elements of the 17th-century organ. They are the largest 18th-century organs in the Americas; they are situated above the walls of the choir, on the epistle side (east) and the gospel side (west).[46] Both organs, damaged by fire in 1967, were restored in 1978. Because both organs had fallen into disrepair again, the gospel organ was re-restored from 2008 to 2009 by Gerhard Grenzing; the restoration of the epistle organ, also by Grenzing, was completed in 2014, and both organs are now playable.[47]

Choir

The choir is where the priest and/or a choral group sings the psalms. It is located in the central nave between the main door and the high altar, and built in a semicircular fashion, much like Spanish cathedrals. It was built by Juan de Rojas between 1696 and 1697.[48] Its sides contain 59 reliefs of various saints done in mahogany, walnut, cedar and a native wood called tepehuaje. The railing that surrounds the choir was made in 1722 by Sangley Queaulo in Macao and placed in the cathedral in 1730.[38]

- Choir and organs

.jpg.webp) View of the choir grate

View of the choir grate View of the side wall of the choir

View of the side wall of the choir Organ

Organ View of the Spanish organ

View of the Spanish organ View of the Mexican organ

View of the Mexican organ View of an organ case from outside the choir area

View of an organ case from outside the choir area

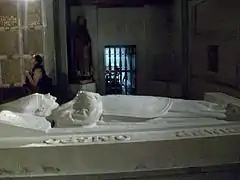

Crypt

The Crypt of the Archbishops is located below the floor of the cathedral beneath the Altar of the Kings. The entrance to the crypt from the cathedral is guarded by a large wooden door behind which descends a winding yellow staircase. Just past the inner entrance is a Mexica-style stone skull. It was incorporated as an offering into the base of a cenotaph to Juan de Zumárraga, the first archbishop of Mexico. Zumárraga was considered to be a benefactor of the Indians, protecting them against the abuses of their Spanish overlords. There is also a natural-sized sculpture of the archbishop atop the cenotaph.

On its walls are dozens of bronze plaques that indicate the locations of the remains of most of Mexico City's former archbishops, including Cardinal Ernesto Corripio y Ahumada. The floor is covered with small marble slabs covering niches containing the remains of other people.[49]

The cathedral contains other crypts and niches where other religious figures are buried, including in the chapels.

- Crypt of the Archbishops of Mexico

The crypt

The crypt Prehispanic stela

Prehispanic stela A crypt

A crypt Zumárraga tomb, in the Chapel of Our Lady of Sorrows

Zumárraga tomb, in the Chapel of Our Lady of Sorrows Archbishops' niches

Archbishops' niches

Restoration

The sinking ground and seismic activity of the area have had an effect on the cathedral's construction and current appearance. Forty-two years were required simply to lay its foundation when it was first built, because even then the Spaniards recognized the danger of constructing such a huge monument in soft soil.[3] However, for political reasons, much, but not all, of the cathedral was built over the remains of pre-Hispanic structures, leading to uneven foundation from the beginning.[50]

Fire of 1967

On 17 January 1967 at 9 pm, a fire caused by an electrical short circuit caused extensive damage to the cathedral. On the Altar of Forgiveness, much of the structure and decoration were damaged including the loss of three paintings; The Holy Face by Alonso López de Herrera, The Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian by Francisco de Zumaya and The Virgin of Forgiveness by Simon Pereyns. The choir section lost 75 of its 99 seats as well a painting by Juan Correa along with many stored books. The two cathedral organs were severely damaged with the partial melting of their pipes. Paintings by Rafael Jimeno y Planas, Juan Correa and Juan Rodriguez Juarez were damaged in other parts of the cathedral. After the fire, authorities recorded the damage but did nothing to try to restore what was damaged. Heated discussions ensued among historians, architects and investigations centering on the moving of the Altar of Forgiveness, as well as eliminating the choir area and some of the railings. In 1972, ecclesiastical authorities initiated demolition of the choir area without authorization from the Federal government but were stopped. The government inventoried what could be saved and named Jaime Ortiz Lajous as director of the project to restore the cathedral to its original condition. Restoration work focused not only on repairing the damage (using archived records and photographs), but also included work on a deteriorating foundation (due to uneven sinking into the ground) and problems with the towers.

The Altars of Forgiveness and of the Kings were subject to extensive cleaning and restorative work. To replace the lost portions on the Altar of Forgiveness, several paintings were added: Escape from Egypt by Pereyns, The Divine Countenance and The Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian. The organs were dismantled with the pipes and inner workings sent to the Netherlands for repair, while the cases were restored by Mexican craftsmen with work lasting until 1977. Reconstruction of the choir area began in 1979 using the same materials as existed before the fire. In addition, any statues in the towers that received more than 50% damage from city pollution were taken out, with replicas created to replace them. Those with less damage were repaired.

Some interesting discoveries were made as restoration work occurred during the 1970s and early 1980s. 51 paintings were found and rescued from behind the Altar of Forgiveness, including works by Juan and Nicolas Rodriguez Juarez, Miguel Cabrera and José de Ibarra. Inside one of the organs, a copy of the nomination of Hernán Cortés as Governor General of New Spain (1529) was found. Lastly, in the wall of the central arch of the cathedral was found the burial place of Miguel Barrigan, the first governor of Veracruz.[13]

Late 20th-century work

The cathedral, along with the rest of the city, has been sinking into the lakebed from the day it was built. However, the fact that the city is a megalopolis with over 18 million people drawing water from underground sources has caused water tables to drop and the sinking to accelerate during the latter half of the 20th century.[51] Sections of the complex such as the cathedral and the tabernacle were still sinking at different rates,[52] and the bell towers were tilting dangerously despite work done in the 1970s.[14][50] For this reason, the cathedral was included in the 1998 World Monuments Watch by the World Monuments Fund.

Major restoration and foundation work began in the 1990s to stabilize the building.[50] Engineers excavated under the cathedral between 1993 and 1998.[52] They dug shafts under the cathedral and placed shafts of concrete into the soft ground to give the edifice a more solid base to rest on.[51] These efforts have not stopped the sinking of the complex, but they have corrected the tilting towers and ensured that the cathedral will sink uniformly.[50]

21st-century work

Since the earthquake in 2017, the cathedral is undergoing a reconstruction to restore the damages caused by the earthquake. During the reconstruction, the workers found 23 lead boxes that contain religious relics such as small paintings and wood or palm crosses.[53] The boxes contained written inscriptions dedicated to specific saints and also indicated that the boxes were found previously by a group of masons and painters in 1810, and reburied. [53]

Cultural value

The cathedral has been a focus of Mexican cultural identity, and is a testament to its colonial history. People often gather there to worship and attend religious services.[21] Researcher Manuel Rivera Cambas reported that the cathedral was built on the site sacred precinct of the Aztecs and with the very stones of their temples so that the Spaniards could lay claim to the land and the people.[3] Hernán Cortés supposedly himself laid the first stone of the original church.[21]

It once was an important religious center, used exclusively by the prominent families of New Spain. At the beginning of Mexican independence, during the First Mexican Empire, Emperor Agustin I was crowned Emperor of Mexico in the cathedral in the presence of the bishops of Puebla, Guadalajara, Durango, and Oaxaca. In 1864, during the Second Mexican Empire, Emperor Maximilian I of Mexico and his consort Empress Carlota, formerly Archduke of Austria and Princess of Belgium, were also crowned with the Imperial Crown of Mexico at the cathedral after their magnificent arrival in the capital of their reign.[54] [55][56][57]

Located on the Zocalo it has, over time, been the focus of social and cultural activities, most of which have occurred in the 20th and 21st centuries. The cathedral was closed for four years while President Plutarco Elías Calles attempted to enforce Mexico's anti-religious laws. Pope Pius XI closed the church, ordering priests to cease their public religious duties in all Mexican churches. After the Mexican government and the papacy came to terms and major renovations were performed on the cathedral, it reopened in 1930.[58]

The cathedral has been the scene of several protests both from the church and to the church, including a protest by women over the Church's exhortation for women not to wear mini-skirts and other provocative clothing to avoid rape,[59] and a candlelight vigil to protest against kidnappings in Mexico.[60] The cathedral itself has been used to protest against social issues. Its bells rang to express the Archdiocese's opposition to the Supreme Court upholding of Mexico City's legalization of abortion.[61]

Probably the most serious recent event occurred on 18 November 2007, when sympathizers of the Party of the Democratic Revolution attacked the cathedral.[62] About 150 protesters stormed into Sunday Mass chanting slogans and knocking over pews. This caused church officials to close and lock the cathedral for a number of days.[63] The cathedral reopened with new security measures, such as bag searches, in place.[62]

See also

References

- ↑ "Dedications of the Cathedral of Mexico" (in Spanish). Archdiocese of Mexico. 2011. Archived from the original on 2012-03-11. Retrieved 2014-09-17.

- ↑ "View of Guadalupe". PEERLESS. Archived from the original on 2012-04-28. Retrieved 2012-05-22.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 Galind, Carmen; Magdelena Galindo (2002). Mexico City Historic Center. Mexico City: Ediciones Nueva Guia. pp. 41–49. ISBN 968-5437-29-7.

- 1 2 "Catedral metropolitana de México". MSN. Archived from the original on 2009-04-12. Retrieved 2008-09-18.

- ↑ "4.3 Artífices de la Catedral de México1". Mexico City Metropolitan Cathedral official website (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 2020-08-03. Retrieved 2019-10-15.

- ↑ "2.13 Estilos artísticos de la Catedral". Mexico City Metropolitan Cathedral website (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 2020-08-03. Retrieved 2019-10-15.

- ↑ "1. Historia de la Catedral de México Introducción1". Mexico City Metropolitan Cathedral official website (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 2020-11-17. Retrieved 2019-10-15.

- ↑ Harris Chynoweth, W. (1872). "The Fall of Maximilian, Late Emperor of Mexico: With an Historical Introduction, the Events Immediately Preceding His Acceptance of the Crown".

- ↑ Butler, John Wesley (1918). History of the Methodist Episcopal Church in Mexico. University of Texas.

- ↑ Campbell, Reau (1907). Campbell's New Revised Complete Guide and Descriptive Book of Mexico. Rogers & Smith Company. Pg.38 .

- ↑ Putman, William Lowell (2001) Arctic Superstars. Light Technology Publishing, LLC. Pg.XVII.

- ↑ "Restos de líderes independentistas en la Catedral de México". Mexico City Metropolitan Cathedral official website (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 2020-08-03. Retrieved 2019-10-15.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Alvarez, Jose Rogelio, ed. (2000). "Catedral de Mexico". Enciclopedia de Mexico (in Spanish). Vol. 3. Mexico City. ISBN 1-56409-034-5.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - 1 2 3 4 "Metropolitan Cathedral Mexico City". Sacred Destinations. Archived from the original on 2020-08-07. Retrieved 2008-09-18.

- ↑ Walter Krickeberg (1964). Las antiguas culturas mexicanas. Economic Culture Fund. p. 109. Archived from the original on 2021-08-12. Retrieved 2020-11-30.

- ↑ Antonio Joachín Ribadeneyra Barrientos (1755). Manual compendio de el regio patronato indiano (in Spanish). pp. 408–409. OCLC 433639112. Archived from the original on 2021-08-12. Retrieved 2020-11-30.

- 1 2 Pedro Gualdi; Luis Ortiz Macedo; Claire Giannini Hoffman (1981). Monumentos de Mejico. Fomento Cultural Banamex. p. 9. OCLC 906915669.

- ↑ López-Cano, Martínez; Pilar, María del (June 2012). "Decretos del Concilio Tercero Provincial Mexicano (1585), edición histórico crítica y estudio preliminar de Luis Martínez Ferrer" [Decrees of the Mexican Third Provincial Council (1585)]. Estudios de Historia Novohispana (in Spanish). 46 (046): 201–204. doi:10.22201/iih.24486922e.2012.046.32492. hdl:20.500.12525/1389.

- ↑ "La Primitiva Catedral de México1". Mexico City Metropolitan Cathedral official website (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 2020-08-04. Retrieved 2019-10-15.

- ↑ Fernando Arellano (1988). El arte hispanoamericano. Universidad Católica Andrés Bello. pp. 88–91. ISBN 9789802440177. Archived from the original on 2020-07-26. Retrieved 2020-11-30.

- 1 2 3 4 "Cathedral Metropolitan". Archived from the original on 2020-08-09. Retrieved 2008-09-18.

- 1 2 "Metropolitan Cathedral of Mexico City –History". Archived from the original on March 13, 2008. Retrieved 2008-09-18.

- ↑ "1.2.9 Las Obras de la Catedral Durante el Resto del Siglo XVII1". Mexico City Metropolitan Cathedral official website (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 2020-08-03. Retrieved 2019-10-16.

- ↑ "1.2.10 Trabajos Durante el Siglo XVIII1". Mexico City Metropolitan Cathedral official website (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 2020-08-03. Retrieved 2019-10-16.

- ↑ Manuel Toussaint (1990). Obras maestras del arte colonial : exposición homenaje a Manuel Toussaint (1890-1990) : catálogo. Mexico City. OCLC 25913924.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ "1.2.12 Conclusión de la Obra1". Mexico City Metropolitan Cathedral (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 2020-08-04. Retrieved 2019-10-16.

- ↑ Cancino, Fabiola (2006-07-21). "Restauran el reloj de la Catedral tras nueve años". El Universal Online México, S.A. de C.V. Archived from the original on 2009-05-20. Retrieved 2009-01-10.

- ↑ PMC (2008-01-17). "Found atop Mexico City Cathedral - Time capsule from 1791". Archived from the original on 2009-05-20. Retrieved 2008-09-18.

- 1 2 3 Noble, John (2000). Lonely Planet Mexico City (in Spanish). Oakland, CA: Lonely Planet Publications. pp. 110–111. ISBN 1-86450-087-5.

- 1 2 3 4 Horz de Via, Elena (1991). Guia Oficial Centro de la Ciudad de Mexico. Mexico City: INAH-SALVAT. pp. 28–30. ISBN 968-32-0540-2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Cano de Mier, Olga (1988). Guia de Forasteros Centro Historico Ciudad de Mexico (in Spanish). Mexico City: Guias Turisticas Banamex. pp. 32–37.

- ↑ Reséndiz Martínez, José Francisco; Olvera Coronel, Lilia Patricia; Vázquez Silva, Luis; Nieto de Pascual, Cecilia. "Especies maderables y agentes patógenos del retablo de los reyes de la Catedral Metropolitana de la Ciudad de México". Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Forestales (in Spanish). Vol. 4, no. 9. Archived from the original on 2016-01-27. Retrieved 2022-01-12.

- ↑ "El Retablo de los Reyes, 'la obra más lucida y costosa de América'". Instituto Latinoamericano de la Comunicación Educativa (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 13 January 2022. Retrieved 12 January 2022.

- ↑ Vargaslugo, Elisa (1974). "Nuevos documentos sobre Gerónimo, Isidoro y Luis de Balbás". Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas de la UNAM (in Spanish). Vol. XII, no. 43. pp. 77–81. doi:10.22201/iie.18703062e.1974.43.992. Archived from the original on 2022-01-13. Retrieved 2022-01-12.

- ↑ "Detalle del Retablo de los Reyes". Instituto Latinoamericano de la Comunicación Educativa (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 13 January 2022. Retrieved 12 January 2022.

- ↑ Fraile Martin, María Isabel (January–April 2009). "Juan Rodríguez Juárez y su contribución al acervo pictórico de la Catedral de Puebla". Boletín de Monumentos Histróricos | Tercera Época (in Spanish). No. 15. National Institute of Anthropology and History. p. 63. Archived from the original on 2021-08-13. Retrieved 2022-01-12.

- ↑ Reséndiz Martínez, José Francisco; Olvera Coronel, Lilia Patricia; Vázquez Silva, Luis; Nieto de Pascual, Cecilia. "Especies maderables y agentes patógenos del retablo de los reyes de la Catedral Metropolitana de la Ciudad de México". Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Forestales (in Spanish). Vol. 4, no. 9. Archived from the original on 2016-01-27. Retrieved 2022-01-12.

- 1 2 3 "Catedral Metropolitano: 478 años de historia". Epoca (in Spanish). Mexico City: Archdiocese of Mexico. 565: 52–59. 1 April 2002.

- ↑ In the chapels, the terms "left-hand" and "right-hand" are used with reference to the main altar of each chapel.

- ↑ Mondragón Jaramillo, Carmen (7 January 2010). "Niños Jesus que obran milagros" [Nino Jesus that performs miracles] (in Spanish). Mexico: INAH. Retrieved January 20, 2010.

- 1 2 El Sol de México (9 November 2008). "Santo Niño Cautivo, patrono de los secuestrados" [Holy Niño Cautivo, patron of the kidnapped]. El Sol de México (in Spanish). Mexico City. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved January 20, 2010.

- ↑ "Tiene arraigo en México la veneración al Niño Dios" [Veneration of the Niño Dios has deep roots in Mexico]. El Universal (in Spanish). Mexico City. Notimex. 2 February 2007. Archived from the original on 4 December 2011. Retrieved January 20, 2010.

- ↑ Pepe, Edward (2011). "From Spain to the New World: the hiring of the Madrid organist Fabián Pérez Ximeno by Mexico City Cathedral". In Richards, Annette (ed.). Keyboard Perspectives. Vol. IV. pp. 27–48. OCLC 803998579.

- ↑ Pepe, Edward (January 2007). "Writing a History of Mexico's Early Organs: A Seventeenth-Century Disposition from the Mexico City Cathedral". In Donahue, Thomas (ed.). Music and Its Questions: Essays in Honor of Peter Williams. Richmond: OHS Press. pp. 49–74. ISBN 978-0-913499-24-5.

- ↑ Pepe, Edward (June 2006). "An Organ by Jorge de Sesma for Mexico City Cathedral". Revista de Musicología. Sociedad Española de Musicologia (SEDEM). 29 (1): 127–162. doi:10.2307/20798165. JSTOR 20798165.

- ↑ Flentrop, Dirk Andries; John Fesperman (1986). "The Organs of Mexico City Cathedral". Smithsonian Studies in History and Technology. 47.

- ↑ "Mexico City's Metropolitan Cathedral completes organ restoration". Global Post. EFE. 14 May 2014. Archived from the original on 2016-03-06. Retrieved 2014-09-17.

- ↑ "Metropolitan Cathedral of Mexico City- The choir". 2007. Archived from the original on August 28, 2008. Retrieved 2008-09-18.

- ↑ Ricardo Pacheco Colín (25 July 2005). "La Cripta de los Arzobispos, una joya escondida en la Catedral" (in Spanish). Gobierno de Presidente Fox. Archived from the original on 1 June 2009. Retrieved 2008-11-20.

- 1 2 3 4 "A Walking Tour of Mexico City". Suzanne Barbezat. 9 December 2008. Archived from the original on 2009-03-10. Retrieved 2008-09-18.

- 1 2 Greste, Peter (8 January 1999). "World: Americas Saving Mexico's sinking cathedral". BBC News. Archived from the original on 2020-11-12. Retrieved 2008-09-18.

- 1 2 Wiley, John; Meli, Roberto; Sánchez, Roberto; Orozco, Bernardo (May 2008). "Evaluation of the measured seismic response of the Mexico City Cathedral". Earthquake Engineering & Structural Dynamics. 37 (10): 1249–1268. doi:10.1002/eqe.808. S2CID 110806380. Retrieved 2008-09-18.

- 1 2 "Relics found in 23 lead boxes in Mexico City cathedral". NBC News. Retrieved 2023-02-06.

- ↑ Harris Chynoweth, W. (1872). "The Fall of Maximilian, Late Emperor of Mexico: With an Historical Introduction, the Events Immediately Preceding His Acceptance of the Crown".

- ↑ Butler, John Wesley (1918). History of the Methodist Episcopal Church in Mexico. University of Texas.

- ↑ Campbell, Reau (1907). Campbell's New Revised Complete Guide and Descriptive Book of Mexico. Rogers & Smith Company. Pg.38 .

- ↑ Putman, William Lowell (2001) Arctic Superstars. Light Technology Publishing, LLC. Pg.XVII.

- ↑ "Mexico City Cathedral". Time. 25 August 1930. Archived from the original on 2014-07-29. Retrieved 2008-09-18.

- ↑ "Protestan mujeres in minifalda frente a catedral Cd. de México" (in Spanish). Xinhua News Agency. 2008-08-17. Archived from the original on 2008-09-07. Retrieved 2008-09-18.

Women in miniskirts protest in front of Mexico City Cathedral

- ↑ "150,000 Mexicans take to the streets to protest a spate of murders and kidnappings". Evening Standard. 31 August 2008. Archived from the original on 2020-07-22. Retrieved 2014-09-17.

- ↑ "Campanas de la Catedral de México repicaron en señal de duelo por ley del aborto" [Cathedral bells tolled in Mexico in mourning for abortion law]. ACI Prensa. 29 August 2008. Archived from the original on 2008-09-14. Retrieved 2008-09-18.

- 1 2 "Message of forgiveness at Mexico City Cathedral". Catholic News Agency. 28 November 2009. Archived from the original on 22 May 2009. Retrieved 18 September 2008.

- ↑ Grillo, Ioan (21 November 2007). "Mexico City's Cathedral closes after anti-Catholic protesters storm building during Mass". Catholic News Agency. Archived from the original on 22 January 2008. Retrieved 18 September 2008.

External links

- Official website

(in Spanish)

(in Spanish) - Photos of Mexico City’s Metropolitan Cathedral, from Have Camera Will Travel

- La Rehabilitación de la Catedral Metropolitana de la Ciudad de México, from the UNAM (in Spanish)

- History of Mexico City’s Metropolitan Cathedral at HiSoUR.com