| Gustafsonia Temporal range: Middle Eocene to Early Oligocene | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Family: | †Amphicyonidae |

| Genus: | †Gustafsonia Tomiya & Tseng, 2016 |

| Species: | †G. cognita |

| Binomial name | |

| †Gustafsonia cognita (Gustafson, 1986) | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

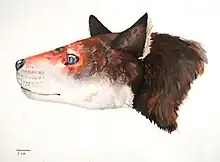

Gustafsonia is an extinct genus of carnivoran belonging to the family Amphicyonidae (a bear dog). The type species, Gustafsonia cognita, was described in 1986 by Eric Paul Gustafson, who originally interpreted it as a miacid and named it Miacis cognitus. It was subsequently considered to be the only species of the diverse genus Miacis that belonged to the crown-group Carnivora, within the Caniformia,[1] and it was ultimately assigned to the family Amphicyonidae.[2] The type specimen or holotype was discovered in Reeve's bonebed, western Texas, in the Chambers Tuff Formation in 1986.[3] The University of Texas holds this specimen. It is the only confirmed fossil of this species.

Morphology

Fossil

The holotype is missing the mandible, upper canines, and zygomatic arch. The remainder of the skull is damaged, but relatively intact.

Teeth

It preserves the old style of many teeth, probably having forty-two, as compared to most modern carnivorans in the low thirties. With the later species of Miacis, the size of the certain teeth were decreasing, namely the foremost premolars. These teeth would eventually be lost all together, resulting in the fewer number of teeth seen in most modern carnivorans, especially feliforms, including extant hyenas, viverrids, herpestid, and the famously few-toothed felids. Most members of Miacoidea have forty four teeth, so this advanced species has already lost two bottom premolars. Though the upper canines are missing, these teeth can be reconstructed due to the foramen for the tooth root remaining intact. These canines were not particularly long or short, though they were not stout or shaped for great stress. The molars of this species were small and not suited for grinding large amounts of material. The premolars show carnassial form that makes carnivorans unique and were good for slicing rather than crushing or grinding.

Comparison to modern species

The skull of G. cognita is long and low. In skull morphology, the African palm civet, Nandinia binotata takes the prize of looking most like its distant relative.

Digital morphology and CT scanning

The information core for the Digital Morphology library is generated using a state-of-the-art high-resolution X-ray computed tomographic (X-ray CT) scanner. This instrument is comparable to a conventional medical diagnostic CAT scanner, but with greater resolution and penetrating power. The CT scanner was custom built and optimally designed to explore the internal structure of natural objects and materials at mega- and microscopic levels. This instrument is at the center of The University of Texas High-Resolution X-ray Computed Tomography Facility (UTCT), a designated NSF-supported Multi-User Facility. Now in its seventh year, UTCT has scanned hundreds of rocks, meteorites, fossils, and modern organisms, providing unique data and visualizations for a wide range of interests in education and research.

The holotype of Gustafsonia cognita was made available to the University of Texas High-Resolution X-ray CT Facility for scanning by Dr. Timothy Rowe of The University of Texas at Austin, Department of Geological Sciences. The specimen was scanned by Richard Ketcham on 3 December 2007 along the coronal axis for a total of 1010 slices. Each 1024×1024-pixel slice is 0.08551 mm thick, with an interslice spacing of 0.08551 mm and a field of reconstruction of 40 mm.[4]

Surface views allow one to roll, pitch, and yaw the specimen to see the fossil as though you were holding it in your hand. A second series is much more in depth slice movies, with coronal, transverse, and sagittal slices of the fossil. The last series is a dynamic cutaway from coronal, transverse, and sagittal angles as well.

Evolution

The mass extinction of the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event left many ecological niches open, allowing various mammalian lineages to move into them during the Paleocene. Contrary to popular belief, many mammals such as the pantodonts and mesonychians became large quickly during the Paleocene rather than remaining small for longer, but this also caused other lineages to remain small to avoid competition, including the creodonts (which are likely not a natural group) and the Carnivoramorpha. As the Eocene continued, some of the creodonts, known as the oxyaenids, became larger and competed with the mesonychians as the dominant hunters in Laurasia; the carnivoramorphs and the other group of “creodonts”, the hyaenodonts, remained relatively small, staying out of the way. At this point, the crown-group Carnivora began to diversify during the middle and late Eocene, when two major lineages appeared-the feliformes (cats, hyenas, civets, palm civets, etc.) and the caniformes (dogs, bears, pinnipeds, skunks, ferrets, amphicyonids, etc.). *Gustafsonia*, being an early amphicyonid, is a caniform. Around this time, the formerly dominant oxyaenids and mesonychians began to decline as a result of climatic changes; open niches left by these predators were quickly filled by some of the carnivorans, namely the feliform nimravids, and by the hyaenodonts; hyaenodonts would remain successful in various predatory niches until the end of the Middle Miocene, but the carnivorans were much more diverse, becoming the dominant group of land predators in Laurasia by the start of the Miocene and fully taking over once hyaenodonts entered terminal decline in the Late Miocene.

Ecology

Reeves bonebed is well known for its oreodonts, especially Bathygenys. This oreodont, related to modern llamas, is very common in the formation, and being small for an oreodont at about thirteen pounds, it would have been hunted by Miacis regularly. The creodont Hyaenodon was also present in the fossil bed, and it is probably that this larger creodont hunted the larger oreodont Merycoidodon who, at over two hundred pounds, would have killed attacking Miacis. The large brontothere Menodus would have been far too large for Miacis, and if anything would have been a danger for the small carnivore. Miacis would have avoided this species completely to avoid injury from massive perissodactylid. The medium-sized herbivores Agriochoerus, Hyracodon, Mesohippus and Leptotragulus, were again probably Hyaenodon prey and Miacis would have left it alone completely. Leptomeryx inhabited the same range and was smaller. Its young would have been ample prey, and the adults might have been tackled. The rodent Ardynomys was of perfect size and would have been hunted by Miacis. Within the region, there were many smaller rodents, and with so many animals in the area that were too large for Miacis to kill, it is likely that the small animal, somewhere between the size of a cat and a begal, would have been a prolific rodent hunter and a hunter of Bathygenys.[5]

References

- ↑ Spaulding, M.; Flynn J.J.; Stucky, R.K. (2010) Anew basal Carnivoramorphan (Mammalia) from the ‘Bridger B’ (Black’s Fork Member, Bridger Formation, Bridgerian NALMA, Middel Eocene) of Wyoming, USA. Paleontology 53: 815-832. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2010.00963.x

- ↑ Susumu Tomiya; Zhijie Jack Tseng (2016). "Whence the beardogs? Reappraisal of the Middle to Late Eocene Miacis from Texas, USA, and the origin of Amphicyonidae (Mammalia, Carnivora)". Royal Society Open Science. 3 (10): 160518. Bibcode:2016RSOS....360518T. doi:10.1098/rsos.160518. PMC 5098994. PMID 27853569.

- ↑ Paleobiology Database. "Miacis cognitus Gustafson 1986 (carnivoran)".

- ↑ Digimorph (Digital morphology). "Miacis cognitus, extinct carnivoran".

- ↑ University of Texas, Austin. "Reeves bonebed". Archived from Bonebed&county=&state=&specid=&geol_form=&epoch=&site_no=&showimage=&geog=&country=&others=&geol=&epoch=&period=&age=&era=&strat=&formation=&group=&horizon=&member=&sorted_by= the original on September 29, 2011.

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help)