| Battle of Milliken's Bend | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Civil War | |||||||

An illustration of the Milliken's Bend battle from the Harper's Weekly periodical, showing black U.S. soldiers battling Confederates. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Hermann Lieb | Henry E. McCulloch | ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

African Brigade 23rd Iowa Infantry Regiment Two gunboats | McCulloch's brigade | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 1,100 | 1,500 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 492 | 185 | ||||||

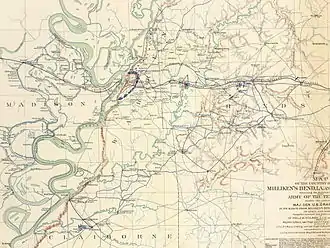

The Battle of Milliken's Bend was fought on June 7, 1863, as part of the Vicksburg Campaign during the American Civil War. Major General Ulysses S. Grant of the Union Army had placed the strategic Mississippi River city of Vicksburg, Mississippi, under siege in mid-1863. Confederate leadership erroneously believed that Grant's supply line still ran through Milliken's Bend in Louisiana, and Major General Richard Taylor was tasked with disrupting it to aid the defense of Vicksburg. Taylor sent Brigadier General Henry E. McCulloch with a brigade of Texans to attack Milliken's Bend, which was held by a brigade of newly-recruited African American soldiers. McCulloch's attack struck early on the morning of June 7, and was initially successful in close-quarters fighting. Fire from the Union gunboat USS Choctaw halted the Confederate attack, and McCulloch later withdrew after the arrival of a second gunboat. The attempt to relieve Vicksburg was unsuccessful. One of the first actions in which African American soldiers fought, Milliken's Bend demonstrated the value of African American soldiers as part of the Union Army.

Background

In the spring of 1863,[2] Major General Ulysses S. Grant of the Union Army began a campaign against the strategic Confederate-held city of Vicksburg, Mississippi. Grant's troops crossed the Mississippi River from the Louisiana side into Mississippi at a point south of Vicksburg in late April.[3] By May 18, the Union army had fought its way to Vicksburg, surrounded it, and initiated the Siege of Vicksburg.[4] During the campaign, Grant had kept a supply base at Milliken's Bend in Louisiana as part of his supply line. Soldiers had been housed at the site before being deployed in the campaign, and a number of hospitals had been established there.[1] During the siege, however, Grant had a different supply line opened: the Union Navy took control of part of the Yazoo River in the Chickasaw Bayou vicinity and established a point from which supplies could be sent overland behind the Union lines.[5] While a position at Milliken's Bend was still held, its importance was greatly reduced, since the Yazoo River position had become Grant's primary supply depot.[6]

Meanwhile, Confederate President Jefferson Davis was pressuring General E. K. Smith, commander of the Trans-Mississippi Department, to attempt to relieve Vicksburg's garrison. Smith was unaware that Grant had moved his supply line to the Yazoo River, and still believed that Milliken's Bend was a primary Union supply depot. Immediate command of the offensive fell to Major General Richard Taylor, who was given a division of Texans known as Walker's Greyhounds. Taylor moved the 5,000-man force to Richmond, Louisiana, but did not believe that the coming expedition had any real chance of disrupting Grant's siege of Vicksburg.[6] On June 5, Taylor learned that Milliken's Bend was no longer a significant supply point, but the planned offensive continued, with hopes of retaking control of the west bank of the Mississippi River and gaining the ability to send food across the river into Vicksburg.[7] At Richmond, on June 6, Taylor detached the 13th Louisiana Cavalry Battalion on a raid against Lake Providence, Louisiana, while Walker's Greyhounds continued to the site of Oak Grove Plantation, where there was a road junction. One Confederate brigade split off to move against a Union position at Young's Point, while Brigadier General Henry E. McCulloch's brigade advanced against Milliken's Bend. A third brigade was held in reserve at Oak Grove.[8]

The Union posts at Milliken's Bend, Young's Point, and Lake Providence had become training grounds for African American soldiers. These soldiers were primarily newly-recruited freed slaves.[9] Union leadership's plan had been to use these soldiers as laborers and camp guards rather than front-line soldiers,[10][11] so they had only received basic military training.[10] At this time, the Colored Troop units were commanded by white officers.[12] Mustering these soldiers into the Union Army faced some opposition, with some believing that they would not fight.[13] The support of several officers, including Major General John A. Logan, however, helped to reduce some of the resistance.[12] The soldiers at Milliken's Bend had no prior experience with firearms before joining the Union Army, and demonstrated very poor marksmanship during training. Colonel Hermann Lieb commanded the camp, which was manned by an infantry brigade of African American soldiers and some cavalry from Illinois.[9]

Both Lieb and Brigadier General Elias Dennis, who commanded the Union troops in the area, suspected that the Confederates were preparing to attack Milliken's Bend.[9] Lieb's 9th Louisiana Infantry Regiment and 10th Illinois Cavalry Regiment had encountered Confederates near Tallulah on June 6 during an expedition towards Richmond. Lieb requested reinforcements, and the 23rd Iowa Infantry Regiment and the ironclad USS Choctaw were sent to Milliken's Bend.[1]

Battle

_(cropped).jpg.webp)

On June 7, McCulloch's 1,500 Confederates marched to Milliken's Bend in the cooler nighttime, and by 02:30 arrived within 1.5 miles of Milliken's Bend.[2] By 03:00, they were within 1 mile (1.6 km) of the Union position. Lieb's 1,100 Union soldiers had constructed a defensive position by forming a breastwork out of cotton bales on top of a levee.[14] The Union pickets were quickly driven back by the Confederates.[1] McCulloch aligned his regiments with the 19th Texas Infantry Regiment, 17th Texas Infantry Regiment, and the 16th Texas Cavalry Regiment, from right to left; the 16th Texas Infantry Regiment was held as a reserve. Lieb's defensive line was held by the 23rd Iowa Infantry Regiment and the U.S. Colored Troops of the 8th Louisiana Infantry Regiment, the 9th Louisiana Infantry Regiment, the 10th Louisiana Infantry Regiment, the 11th Louisiana Infantry Regiment, the 13th Louisiana Infantry Regiment, and the 1st Mississippi Infantry Regiment.[15] The main Union line fired a volley that temporarily slowed the Confederate attack,[16][17] but the poorly trained African American soldiers were largely unable to reload their weapons before the Confederate charge continued and became close-quarters fighting. Bayonets were used in the fighting, and the Union defenders were driven back.[17] Lieb's men fell back to a second levee, and the Confederates charged, yelling that no mercy would be given.[16]

During this stage of the fighting, few shots were fired, as the use of rifles as blunt weapons and bayonets was more common. By 04:00, the Confederates seemed to have victory, but they then made the mistake of exposing themselves on the top of the levee. Heavy fire from the large guns of USS Choctaw drove McCulloch's men back off the levee. Confederate leadership was unable to get the Texans to attack the levee again.[18] McCulloch requested reinforcements to continue the fighting, but another Union vessel, the timberclad USS Lexington, arrived around 09:00.[17][19] McCulloch withdrew his men off the field back to Oak Grove Plantation in the face of the gunboats.[17][20]

Aftermath and preservation

The fight at Milliken's Bend cost the Union 492 men: 119 killed, 241 wounded, and 132 missing.[21] Many of the missing men were African American soldiers who had been captured and were returned to slavery.[22] All but 65 of the Union casualties were incurred by the Colored Troops.[20] The 9th Louisiana Infantry was particularly hard hit, losing 68 percent of its strength. This was the greatest percentage loss by any African American regiment during the entire war.[23] Their number of dead, at 66, was the highest number of killed in action of any Union regiment (black or white) during a single day in the entire Vicksburg campaign.[24] Furthermore, this figure of killed in action is 23 percent of their starting force - exceeding the 19 percent killed of the famous 1st Minnesota Infantry Regiment at the Battle of Gettysburg.[23] The Confederates lost 185 men.[19][20]

Rumors of the execution of captured Union soldiers reached Grant, who asked Taylor about the reports. Taylor denied that any executions occurred.[lower-alpha 1]

| Unit | Officers Killed | Men Killed | Officers Wounded | Men Wounded | Officers Missing | Men Missing | Totals |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16th Texas Infantry Regiment | 0 | 2 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| 17th Texas Infantry Regiment | 1 | 20 | 4 | 61 | 0 | 3 | 92 |

| 19th Texas Infantry Regiment | 0 | 2 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 6 | 19 |

| 16th Texas Cavalry Regiment | 1 | 8 | 6 | 41 | 1 | 0 | 67 |

The other two prongs of the coordinated Confederate attacks accomplished little at the Battle of Young's Point and the Battle of Lake Providence.[22] The column sent to Young's Point was delayed by bad guides and a washed-out bridge, and did not reach the Union camp until 10:30. After watching additional Union troops arrive at the camp, along with the gunboats, the Confederates withdrew without a fight.[27] After Milliken's Bend, the Confederates fell back to Monroe, Louisiana, and Taylor travelled to Alexandria, Louisiana, where he focused more attention on the Union forces at New Orleans, Louisiana, than Vicksburg.[10] Smith and the Trans-Mississippi Confederates no longer were able to influence the outcome of the Siege of Vicksburg. The city surrendered on July 4.[28] The position at Milliken's Bend had fallen out of relevance not long after the battle when the men and supplies stored there were transferred to Young's Point.[29]

Parts of the site of the battle have been destroyed by changes in the course of the Mississippi River.[2] A 2010 study by the American Battlefield Protection Program found that of the over 17,000 acres (6,900 ha) of the battlefield, about 2,000 acres (810 ha) were potentially eligible to be listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[30] At the time of the study, there was no public interpretation of the battle at the site.[31] As of March 2021, a commemorative plaque for Milliken's Bend exists on a roadside near Richmond, and exhibits discussing the battle are present at Vicksburg National Military Park.[32] Additionally, an interpretive exhibit exists at Grant's Canal in Louisiana.[2]

Significance and legacy

Leaders on both sides noted the performance of the African American troops at Milliken's Bend. Unionist Charles Dana reported that the action convinced many in the Union Army to support the enlistment of African American soldiers.[22] Dennis stated "it is impossible for men to show greater gallantry than the Negro troops in this fight."[19] Grant described the battle as the first significant engagement in which the Colored Troops had seen combat,[lower-alpha 2][20] described their conduct as "most gallant" and said that "with good officers they will make good troops."[33] He later praised them in his 1885 memoir, stating "These men were very raw, having all been enlisted since the beginning of the siege, but they behaved well."[34] Confederate leader McCulloch later reported that while the white Union troops had been routed, the Colored Troop had fought with "considerable obstinacy."[16] One modern historian wrote in 1960 that the fighting at Milliken's Bend brought "the acceptance of the Negro as a soldier", which was important to "his acceptance as a man."[29]

U.S. Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton also praised the performance of black U.S. soldiers in the battle. He stated that their competent performance in the battle proved wrong those who had opposed their service:

Many persons believed, or pretended to believe, and confidently asserted, that freed slaves would not make good soldiers; they would lack courage, and could not be subjected to military discipline. Facts have shown how groundless were these apprehensions. The slave has proved his manhood, and his capacity as an infantry soldier, at Milliken's Bend, at the assault upon Port Hudson, and the storming of Fort Wagner.

Notes

- ↑ Historian James G. Hollandsworth wrote in 1994 that there was no evidence that Taylor's denial of the executions was a lie, although he does list two white officers captured in the battle in a table of "officers most likely executed after being captured by Confederate forces".[25]

- ↑ United States Colored Troops had previously fought in the minor Skirmish at Island Mound in Missouri in late 1862.[20]

References

- 1 2 3 4 Kennedy 1998, p. 173.

- 1 2 3 4 "Battle of Milliken's Bend, June 7, 1863 - Vicksburg National Military Park". www.nps.gov. Retrieved 2022-06-23.

- ↑ Winschel 1998, pp. 157–158.

- ↑ Bearss 1998, p. 171.

- ↑ Miller 2019, p. 432.

- 1 2 Miller 2019, pp. 452–453.

- ↑ Bigelow 1960, pp. 160–161.

- ↑ Shea & Winschel 2003, pp. 163–164.

- 1 2 3 Miller 2019, p. 453.

- 1 2 3 Foote 1995, p. 259.

- ↑ Miller 2019, p. 337.

- 1 2 Miller 2019, pp. 336–337.

- ↑ Bigelow 1960, p. 160.

- ↑ Miller 2019, pp. 453–454.

- ↑ "Battle of Milliken's Bend, June 7, 1863". National Park Service. April 7, 2017. Retrieved 9 February 2021.

- 1 2 3 Miller 2019, p. 454.

- 1 2 3 4 Shea & Winschel 2003, p. 164.

- ↑ Miller 2019, pp. 454–455.

- 1 2 3 Kennedy 1998, p. 175.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Miller 2019, p. 455.

- ↑ Barnickel 2013, p. 204.

- 1 2 3 Shea & Winschel 2003, p. 165.

- 1 2 Barnickel 2013, p. 103.

- ↑ Barnickel 2013, pp. 205–206.

- ↑ Hollandsworth 1994, pp. 479, 489.

- ↑ Official Records 1889, p. 470.

- ↑ "Young's Point, January – July, 1863". National Park Service. April 14, 2015. Retrieved 2 March 2021.

- ↑ Shea & Winschel 2003, pp. 165, 178.

- 1 2 Bigelow 1960, p. 163.

- ↑ National Park Service 2010, p. 15.

- ↑ National Park Service 2010, p. 20.

- ↑ "Milliken's Bend Battlefield". American Battlefield Trust. Retrieved 19 March 2021.

- ↑ Foote 1995, p. 260.

- ↑ "The Project Gutenberg eBook of Memoirs of U. S. Grant, Complete by Ulysses S. Grant".

- ↑ The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union. Washington, D.C.: United States Department of War. 1899. p. 1,132.

- ↑ Hargrove, Hondon B. (19 September 2003). Black Union Soldiers in the Civil War. McFarland. p. 108. ISBN 9780786416974. Retrieved March 16, 2016.

Sources

- Barnickel, Linda (2013). Milliken's Bend: A Civil War Battle in History and Memory. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8071-4992-8.

- Bearss, Edwin C. (1998). "Battle and Siege of Vicksburg, Mississippi". In Kennedy, Frances H. (ed.). The Civil War Battlefield Guide (2nd ed.). Boston/New York: Houghton Mifflin. pp. 164–167. ISBN 978-0-395-74012-5.

- Bigelow, Martha M. (July 1960). "The Significance of Milliken's Bend in the Civil War". The Journal of Negro History. 45 (3): 156–163. doi:10.2307/2716258. JSTOR 2716258. S2CID 149750795.

- Foote, Shelby (1995) [1963]. The Beleaguered City: The Vicksburg Campaign (Modern Library ed.). New York: The Modern Library. ISBN 0-679-60170-8.

- Hollandsworth, James G. (Autumn 1994). "The Execution of White Officers from Black Units by Confederate Forces during the Civil War". Louisiana History. 35 (4): 475–489. JSTOR 4233150.

- Kennedy, Frances H., ed. (1998). The Civil War Battlefield Guide (2nd ed.). Boston/New York: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-74012-5.

- Miller, Donald L. (2019). Vicksburg: Grant's Campaign that Broke the Confederacy. New York, New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4516-4139-4.

- Official Records (1889). "The War of the Rebellion; A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Volume XXIV, Part II". Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. Retrieved January 14, 2023.

- Shea, William L.; Winschel, Terrence J. (2003). Vicksburg Is the Key: The Struggle for the Mississippi River. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-9344-1.

- Update to the Civil War Sites Advisory Commission Report on the Nation's Civil War Battlefields: State of Louisiana (PDF). Washington, D. C.: National Park Service. October 2010. Retrieved February 9, 2021.

- Winschel, Terrence J. (1998). "Chickasaw Bayou, Mississippi". In Kennedy, Frances H. (ed.). The Civil War Battlefield Guide (2nd ed.). Boston/New York: Houghton Mifflin. pp. 154–156. ISBN 978-0-395-74012-5.

Further reading

- "Battle of Milliken's Bend, June 7, 1863". National Park Service. 2017.

- Lowe, Richard G. "Battle on the Levee: The Fight at Milliken's Bend." In Black Soldiers in Blue: African American Troops in the Civil War Era, edited by John David Smith, 107–135. University of North Carolina Press, 2002.

- Sears, Cyrus. Paper of Cyrus Sears (The Battle of Milliken's Bend), Columbus, OH: F.J. Heer Printing, 1909.

- Winschel, Terrence J. "To Rescue Gibraltar: John Walker's Texas Division and Its Expedition to Relieve Fortress Vicksburg." Civil War Regiments 3, no. 3 (1993): 33–58.

External links

- Milliken's Bend: A Civil War Battle in History and Memory

- PBS' Timeline: African Americans in the Civil War; see June 7, 1863: Milliken's Bend-Louisiana

- Battle of Milliken's Bend – Pantagraph (Bloomington, IL newspaper)

32°26′N 91°06′W / 32.44°N 91.10°W