| Ming Ancestors Mausoleum | |

|---|---|

明祖陵 | |

The Southern Gate of the tomb complex | |

Location in Jiangsu | |

| General information | |

| Architectural style | Chinese (Ming) |

| Town or city | Xuyi Huai'an Prefecture Jiangsu Province |

| Country | China |

| Coordinates | 33°4′55.81″N 118°28′39.63″E / 33.0821694°N 118.4776750°E |

| Construction started | Hongwu 19[1] 1386[2] |

| Completed | Yongle 11[1] c. 1413 |

| Ming Ancestors Mausoleum | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||

| Chinese | 明祖陵 | ||||||||

| Literal meaning | Tomb of the Ancestors of the Ming | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| First Tomb of the Ming | |||||||||

| Chinese | 明代第一陵 | ||||||||

| Literal meaning | First Burial Mound of the Ming Era | ||||||||

| |||||||||

The Ming Ancestors Mausoleum, Ming Ancestor Tomb,[3] or Zuling Tomb[4] was the first imperial mausoleum complex of the Ming dynasty, constructed at a geomantically advantageous site near the inlet of the Huai River[5] into the west side of Hongze Lake in present-day Xuyi County, Huai'an Prefecture, Jiangsu Province, China. Built between 1386 and 1413 by Zhu Yuanzhang—the Hongwu Emperor who founded the Ming—and his son Zhu Di the Yongle Emperor to display their filial piety,[6] it was located north of the town of Sizhou, where the ancestors of the dynasty had lived. The remains of the Hongwu Emperor's grandfather Zhu Chuyi are known to have been disintered and moved to the site. He, his father Zhu Sijiu, and his grandfather Zhu Bailiu[2] were posthumously revered at the site as honorary emperors, Zhu Chuyi as the Xi Ancestor of the Ming (Xizu), Zhu Sijiu as the Yi Ancestor of the Ming (Yizu), and Zhu Bailiu as the De Ancestor of the Ming (Dezu).[2]

The site was flooded by the lake in the 1680s, when the Yellow River still flowed into the Huai. It was not uncovered until the 1960s. During the 1970s and 1980s, earthworks were raised to protect the site from further flooding, after which it was restored as a cultural tourism site by the State Administration of Cultural Heritage of the People's Republic of China. Most of the original statues of the sacred way have been recovered and restored, although some of the gates and halls remain as ruins.

History

Zhu Yuanzhang, the Hongwu Emperor of the Ming, began construction of the complex in the first,[3] 18th,[3] or 19th year of his reign[1] using the Chinese lunisolar calendar (c. 1368, 1385, or 1386). It is considered the first tomb of the Ming.[1] His grandfather Zhu Chuyi (朱初一, Zhū Chūyī) was exhumed and reburied within the complex; the other two mausoleums for his great-grandfather Zhu Sijiu (朱四九, Zhū Sìjiǔ) and Zhu Bailiu (朱百六, Zhū Bǎiliù) are empty and honorary.[1] The Xiangdian Hall (享殿,, Xiǎngdiàn) was built in the 20th[1] or 21st year[3] of his reign (c. 1387 or 1388). The complex allowed the men to receive veneration befitting their new status, having been posthumously elevated as the Yu, Heng, and Xuan Emperors of the Ming (明裕帝, Míng Yùdì; 明恒帝, Míng Héngdì; 明玄帝, Míng Xuándì).[1] Zhu Yuanzhang's son Zhu Di, the Yongle Emperor, built the Lingxing Gate (櫺星門, Língxīngmén) and the outermost wall in the 11th year of the Yongle Era (c. 1413),[1] completing the burial complex.[3]

In the 19th year of the reign of the Kangxi Emperor of the Qing (c. 1680),[3] the Yellow River—then still flowing south of Shandong—changed its course and fully merged into the Huai. This quickly accumulated river sediment that blocked the previous course of the Huai, redirecting most of its flow into Hongze Lake, which submerged the mausoleum complex along with the nearby city of Sizhou.[3]

In the spring of 1963 or 1964,[3] the waters of Hongze Lake receded enough that locals began to notice Tang and Song-looking statues appearing along the muddy shore. The Cultural Revolution delayed any official interest in the ancient relics. Local and provincial officials began excavation and reconstruction in 1976,[3] the last year of Mao Zedong's rule. A new bridge across the Huai had to be constructed in 1977 to allow the necessary personnel and equipment to reach the site from Xuyi.[3] Beginning in 1978, a 2,700-meter (1.7 mi) embankment was constructed to protect the site from any further flooding.[3] About 15 meters (49 ft) high, it tapers from 20 meters (66 ft) wide at the bottom to about 6 meters (20 ft) wide at the top.[3] In 1980, the Jiangsu Department of Culture and the national State Administration of Cultural Heritage allocated funds for further repairs. By 1982, the surviving stone statues had been pieced back together and the sacred way repaved.[3] Its original Golden Brook Bridge (金水橋, Jīnshuǐ Qiáo) was so damaged that it had to be entirely replaced, although surviving fragments are preserved at the site's exhibition hall.[3] Only one of the site's walls was rebuilt, and none of the site's original memorial stele have survived intact.[3] The original Xiang Hall and Pei Hall were thought destroyed and without remains, but surfaced during a drought in May 2011.

In front of the mausoleum there are several gravestones and ornamental columns which are preserved. Today, the total area of the mausoleum is 351,000 square meters (87 acres). It contains over 9700 trees, including pines, cypresses, poplars, and willows. The sacred way is among the most well preserved in China. An arch bridge and five exhibition rooms have been newly built.[7] Prolonged drought along the Yangtze River[8] and Huai River lowered the level of Hongze Lake during the 2010s. The nine arches of the Ming Ancestors Mausoleum, beams under the arches, and most of the top of the paved path leading to the mausoleum are buried deep under the silt in the pond, only showing an outline. In order to protect the cultural relics after being unearthed, the site was submerged again.

The site has been generally ignored in scholarship,[9][3] but was accorded provincial protection as an important cultural site in March 1982 and national protection on 21 January 1996.[3]

Legends

Several legends surround the establishment of the tombs. One holds that a Taoist monk selected the site for the Hongwu Emperor based its superlative fengshui and qi.[3] Another is that the area was dear to the emperor's heart because a separate Taoist in Sizhou had told Zhu Wusi that his son would later rule all China.[3] A third is that the location was the site of both Zhu Yuanzhang's conception and his grandfather's death.[3]

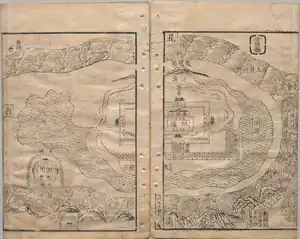

Layout

The site closely followed fengshui principles, establishing a template that would be copied by other tombs through the Ming and Qing dynasties.[6] It was in a broad valley with hills to the north, lower hills east and west, and a southern-facing slope with good drainage.[6] A main sacred way was built through the center, several li long.[6] The entrance of the way was a portico with several doors for visitors of differing status, after which it passed through or beside several courtyards and buildings including a reception pavilion and a commemorative pavilion housing the deceased's tablets of divine merit, followed by rows of paired stone statuary (石象, shíxiàng) representing symbolic animals and effigies of ministers and generals.[6] In the case of Ming Zuling, the statues begin with two pairs of qilin and then feature six pairs of stone lions, a pair of Song-style stone columns (華表, huábiǎo), a pair of horse officers (馬官, mǎguān), a pair of mounted messengers (qianma shizhe), a pair of saddle horses, and a second pair of horse officers. After crossing a bridge, there are two pairs of civil officers (文臣, wénchén), two pairs of generals (武將, wǔjiàng), and last two pairs of scholar-bureaucrats (進士, jìntshì) or eunuchs (太監, tàijiàn).[3]

After stone bridges over geomantically placed streams and a dragon and phoenix portico, a second complex of buildings offered a hall of meditation and a memorial tower leading to the burial mound.[6] The mausoleums themselves held traditional trapezoidal tombs and followed the usual symmetrical arrangement of the burial chamber from the Qin until Zhu Yuanzhang's own burial.[10] This return to traditional Chinese practice marked a notable break with the Mongol Yuan.[3] A feature carried over from the Tang and Song but not later repeated was the surrounding of the site with three successive walls, the outermost and middle made of earth and the innermost from red brick.[3]

One of the messengers on the right side of the sacred way

One of the messengers on the right side of the sacred way The half-moon pool, submerged "doors", and wooded burial mound

The half-moon pool, submerged "doors", and wooded burial mound

See also

- Ming dynasty, Hongwu Emperor, & Yongle Emperor

- Ming Huangling, the tomb of Zhu Yuanzhang's parents Zhu Wusi and Lady Chen in Fengyang, Anhui

- Imperial Tombs of the Ming and Qing Dynasties

- Hongze Lake, Huai River, & Yellow River

- State Administration of Cultural Heritage

References

Citations

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Yuanlin (2008).

- 1 2 3 SACH (2000), p. 173.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 Danielson (2008).

- ↑ SACH (2000), p. 171.

- ↑ "Huaian". Jiangsu.NET,2006-2011. Retrieved 24 April 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 SACH (2000), p. 179.

- ↑ "Ming Ancestors Mausoleum". china daily. 中国日报. 2 June 2011. Retrieved 24 April 2012.

- ↑ "Yangtze River". 中国文化网, CHINACULTURE.ORG. Archived from the original on June 8, 2012. Retrieved April 22, 2012.

- ↑ Paludan (1991).

- ↑ SACH (2000), p. 253.

Bibliography

- State Administration of Cultural Heritage of the People's Republic of China (2 December 2000), "Supplementary Explanations", Imperial Tombs of the Ming and Qing Dynasties (PDF), Paris: UNESCO World Heritage Commission, pp. 170 ff.

- "江苏淮安明祖陵 [Jiangsu Huai'an Mingzuling, The Ancestral Tombs of the Ming in Huai'an, Jiangsu]", 中国景观网 [Zhongguo Jingguan Wang] (in Chinese), Hangzhou: Zhenjiang Academy of Forestry, 2008.

- Danielson, Eric N. (December 2008), "The Ming Ancestor Tomb", China Heritage Quarterly, Canberra: Australian National University.

- Paludan, Ann (1991), The Ming Tombs, Hong Kong: Oxford University Press.

Further reading

- Jiang Zhongjian (1990), 《明代第一陵》 [Mingdai Diyi Ling, First Tomb of the Ming] (in Chinese), Jiangsu Guji Chubanshe.

- Qi Shancheng (2000), "明祖陵" "[Ming Zuling, Ancestral Tombs of the Ming ]", 《江苏政协》 [Jiangsu Zhengxie, Jiangsu Consultative Conference] (in Chinese), Jiangsu Province Consultative Conference Committee.