| Facial muscles | |

|---|---|

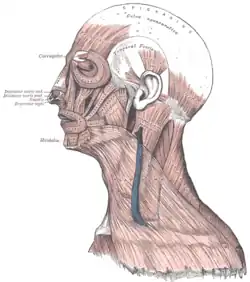

Head | |

Lateral head anatomy | |

| Details | |

| Nerve | facial nerve |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | musculi faciei |

| MeSH | D005152 |

| TA98 | A04.1.03.001 |

| TA2 | 2060 |

| FMA | 71288 |

| Anatomical terms of muscle | |

The facial muscles are a group of striated skeletal muscles supplied by the facial nerve (cranial nerve VII) that, among other things, control facial expression. These muscles are also called mimetic muscles. They are only found in mammals, although they derive from neural crest cells found in all vertebrates. They are the only muscles that attach to the dermis.[1]

Structure

The facial muscles are just under the skin (subcutaneous) muscles that control facial expression. They generally originate from the surface of the skull bone (rarely the fascia), and insert on the skin of the face. When they contract, the skin moves. These muscles also cause wrinkles at right angles to the muscles’ action line.[2]

Nerve supply

The facial muscles are supplied by the facial nerve (cranial nerve VII), with each nerve serving one side of the face.[2] In contrast, the nearby masticatory muscles are supplied by the mandibular nerve, a branch of the trigeminal nerve (cranial nerve V).

List of muscles

The facial muscles include:[3]

- Occipitofrontalis muscle

- Temporoparietalis muscle

- Procerus muscle

- Nasalis muscle

- Depressor septi nasi muscle

- Orbicularis oculi muscle

- Corrugator supercilii muscle

- Depressor supercilii muscle

- Auricular muscles (anterior, superior and posterior)

- Orbicularis oris muscle

- Depressor anguli oris muscle

- Risorius

- Zygomaticus major muscle

- Zygomaticus minor muscle

- Levator labii superioris

- Levator labii superioris alaeque nasi muscle

- Depressor labii inferioris muscle

- Levator anguli oris

- Buccinator muscle

- Mentalis

The platysma is supplied by the facial nerve. Although it is mostly in the neck and can be grouped with the neck muscles by location, it can be considered a muscle of facial expression due to its common nerve supply.

The stylohyoid muscle, stapedius and posterior belly of the digastric muscle are also supplied by the facial nerve, but are not considered muscles of facial expression.

Facial muscles by type of movement

| Movement[4] | Target | Target motion or direction | Prime mover | Origin | Insertion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raising eyebrows (e.g., showing surprise) | Skin of scalp | Anterior | Occipitofrontalis frontal belly | Epicraneal aponeurosis | Underneath skin of forehead |

| Tensing and retracting scalp | Skin of scalp | Posterior | Occipitofrontalis, occipital belly | Occipital bone; mastoid process (temporal bone) | Epicraneal aponeurosis |

| Lowering eyebrows (e.g., scowling, frowning) | Skin underneath eyebrows | Inferior | Corrugator supercilii | Frontal bone | Skin underneath eyebrow |

| Flaring nostrils | Nasal cartilage (pushes nostrils open when cartilage is compressed) | Inferior compression; posterior compression | Nasalis | Maxilla | Nasal bone |

| Raising upper lip | Upper lip | Elevation | Levator labii superioris | Maxilla | Underneath skin at corners of the mouth; orbicularis oris |

| Lowering lower lip | Lower lip | Depression | Depressor labii inferioris | Mandible | Underneath skin of lower lip |

| Opening mouth and sliding lower jaw left and right | Lower jaw | Depression, lateral | Depressor angulus oris | Mandible | Underneath skin at corners of mouth |

| Smiling | Corners of mouth | Lateral elevation | Zygomaticus major | Zygomatic bone | Underneath skin at corners of mouth (dimple area), orbicularis oris |

| Shaping of lips (as during speech) | Lips | Multiple | Orbicularis oris | Tissue surrounding lips | Underneath skin at corners of the mouth |

| Lateral movement of cheeks (e.g., sucking on a straw; also used to compress air in mouth while blowing) | Cheeks | Lateral | Buccinator | Maxilla, mandible; sphenoid bone (via pterygomandibular raphae) | Orbicularis oris |

| Pursing of lips by straightening them laterally | Corners of mouth | Lateral | Risorius | Fascia of parotid salivary gland | Underneath the skin at corners of the mouth |

| Protrusion of lower lip (e.g., pouting expression) | Lower lip and skin of chin | Protraction | Mentalis | Mandible | Underneath skin of chin |

Development

The facial muscles are derived from the second branchial/pharyngeal arch. They, like the branchial arches, originally derive from neural crest cells. In humans, they typically begin forming around the eighth week of embryonic development.[1]

Clinical significance

An inability to form facial expressions on one side of the face may be the first sign of damage to the nerve of these muscles. Damage to the facial nerve results in facial paralysis of the muscles of facial expression on the involved side. Paralysis is the loss of voluntary muscle action; the facial nerve has become damaged permanently or temporarily. This damage can occur with a stroke, Bell palsy, or parotid salivary gland cancer (malignant neoplasm) because the facial nerve travels through the gland. The parotid gland can also be damaged permanently by surgery or temporarily by trauma. These situations of paralysis not only inhibit facial expression but also seriously impair the patient’s ability to speak, either permanently or temporarily.[2]

See also

References

- 1 2 Wilkins, Adam S. (2017). "History of the Face I". Making Faces. Belknap Press. p. 169. ISBN 9780674725522.

- 1 2 3 Illustrated Anatomy of the Head and Neck, Fehrenbach and Herring, Elsevier, 2012, page 89

- ↑ Kyung Won, PhD. Chung (2005). Gross Anatomy (Board Review). Hagerstown, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 364. ISBN 0-7817-5309-0.

- ↑

This article incorporates text available under the CC BY 4.0 license. Betts, J Gordon; Desaix, Peter; Johnson, Eddie; Johnson, Jody E; Korol, Oksana; Kruse, Dean; Poe, Brandon; Wise, James; Womble, Mark D; Young, Kelly A (June 8, 2023). Anatomy & Physiology. Houston: OpenStax CNX. 11.3 Axial muscles of the head, neck and back. ISBN 978-1-947172-04-3.

This article incorporates text available under the CC BY 4.0 license. Betts, J Gordon; Desaix, Peter; Johnson, Eddie; Johnson, Jody E; Korol, Oksana; Kruse, Dean; Poe, Brandon; Wise, James; Womble, Mark D; Young, Kelly A (June 8, 2023). Anatomy & Physiology. Houston: OpenStax CNX. 11.3 Axial muscles of the head, neck and back. ISBN 978-1-947172-04-3.

External links

- ARTNATOMY: Anatomical Basis of Facial Expression Learning Tool

- lesson1 at The Anatomy Lesson by Wesley Norman (Georgetown University)

- Facial muscles at PracticeAnatomy