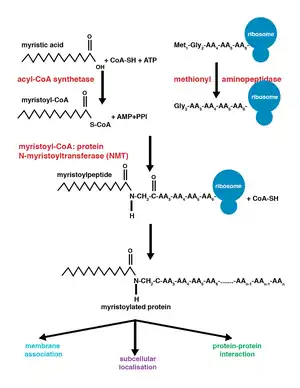

Myristoylation is a lipidation modification where a myristoyl group, derived from myristic acid, is covalently attached by an amide bond to the alpha-amino group of an N-terminal glycine residue.[1] Myristic acid is a 14-carbon saturated fatty acid (14:0) with the systematic name of n-tetradecanoic acid. This modification can be added either co-translationally or post-translationally. N-myristoyltransferase (NMT) catalyzes the myristic acid addition reaction in the cytoplasm of cells.[2] This lipidation event is the most common type of fatty acylation [3] and is present in many organisms, including animals, plants, fungi, protozoans [4] and viruses. Myristoylation allows for weak protein–protein and protein–lipid interactions[5] and plays an essential role in membrane targeting, protein–protein interactions and functions widely in a variety of signal transduction pathways.

Discovery

In 1982, Koiti Titani's lab identified an "N-terminal blocking group" on the catalytic subunit of cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase in cows as n-tetradecanoyl.[6] Almost simultaneously in Claude B. Klee's lab, this same N-terminal blocking group was further characterized as myristic acid.[7] Both labs made this discovery utilizing similar techniques: mass spectrometry and gas chromatography.[6][7]

N-myristoyltransferase

The enzyme N-myristoyltransferase (NMT) or glycylpeptide N-tetradecanoyltransferase is responsible for the irreversible addition of a myristoyl group to N-terminal or internal glycine residues of proteins. This modification can occur co-translationally or post-translationally. In vertebrates, this modification is carried about by two NMTs, NMT1 and NMT2, both of which are members of the GCN5 acetyltransferase superfamily.[8]

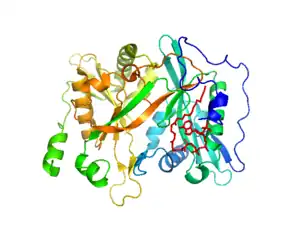

Structure

The crystal structure of NMT reveals two identical subunits, each with its own myristoyl CoA binding site. Each subunit consists of a large saddle-shaped β-sheet surrounded by α-helices. The symmetry of the fold is pseudo twofold. Myristoyl CoA binds at the N-terminal portion, while the C-terminal end binds the protein.[9]

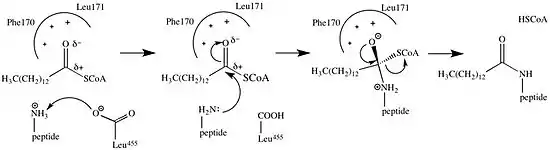

Mechanism

The addition of the myristoyl group proceeds via a nucleophilic addition-elimination reaction. First, myristoyl coenzyme A (CoA) is positioned in its binding pocket of NMT so that the carbonyl faces two amino acid residues, phenylalanine 170 and leucine 171.[9] This polarizes the carbonyl so that there is a net positive charge on the carbon, making it susceptible to nucleophilic attack by the glycine residue of the protein to be modified. When myristoyl CoA binds, NMT reorients to allow binding of the peptide. The C-terminus of NMT then acts as a general base to deprotonate the NH3+, activating the amino group to attack at the carbonyl group of myristoyl-CoA. The resulting tetrahedral intermediate is stabilized by the interaction between a positively charged oxyanion hole and the negatively charged alkoxide anion. Free CoA is then released, causing a conformational change in the enzyme that allows the release of the myristoylated peptide.[2]

Co-translational vs. post-translational addition

Co-translational and post-translational covalent modifications enable proteins to develop higher levels of complexity in cellular function, further adding diversity to the proteome.[10] The addition of myristoyl-CoA to a protein can occur during protein translation or after. During co-translational addition of the myristoyl group, the N-terminal glycine is modified following cleavage of the N-terminal methionine residue in the newly forming, growing polypeptide.[1] Post-translational myristoylation typically occurs following a caspase cleavage event, resulting in the exposure of an internal glycine residue, which is then available for myristic acid addition.[8]

Functions

Myristoylated proteins

| Protein | Physiological Role | Myristoylation Function |

|---|---|---|

| Actin | Cytoskeleton structural protein | Post-translational myristoylation during apoptosis [8] |

| Bid | Apoptosis promoting protein | Post-translational myristoylation after caspase cleavage targets protein to mitochondrial membrane[8] |

| MARCKS | actin cross-linking when phosphorylated by protein kinase C | Co-translational myristoylation aids in plasma membrane association |

| G-Protein | Signaling GTPase | Co-translational myristoylation aids in plasma membrane association[11] |

| Gelsolin | Actin filament-severing protein | Post-translational myristoylation up-regulates anti-apoptotic properties [8] |

| PAK2 | Serine/threonine kinase cell growth, mobility, survival stimulator | Post-translational myristoylation up-regulates apoptotic properties and induces plasma membrane localization[8] |

| Arf | vesicular trafficking and actin remodeling regulation | N-terminus myristoylation aids in membrane association |

| Hippocalcin | Neuronal calcium sensor | Contains a Ca2+/myristoyl switch |

| FSP1 | Apoptosis-inducing factor mitochondria-associated 2 (AIFM2) | Facilitates the association of FSP1 with the lipid-bilayer which enables ferroptosis resistance.[12] |

Myristoylation molecular switch

Myristoylation not only diversifies the function of a protein, but also adds layers of regulation to it. One of the most common functions of the myristoyl group is in membrane association and cellular localization of the modified protein. Though the myristoyl group is added onto the end of the protein, in some cases it is sequestered within hydrophobic regions of the protein rather than solvent exposed.[5] By regulating the orientation of the myristoyl group, these processes can be highly coordinated and closely controlled. Myristoylation is thus a form of "molecular switch."[13]

Both hydrophobic myristoyl groups and "basic patches" (highly positive regions on the protein) characterize myristoyl-electrostatic switches. The basic patch allows for favorable electrostatic interactions to occur between the negatively charged phospholipid heads of the membrane and the positive surface of the associating protein. This allows tighter association and directed localization of proteins.[5]

Myristoyl-conformational switches can come in several forms. Ligand binding to a myristoylated protein with its myristoyl group sequestered can cause a conformational change in the protein, resulting in exposure of the myristoyl group. Similarly, some myristoylated proteins are activated not by a designated ligand, but by the exchange of GDP for GTP by guanine nucleotide exchange factors in the cell. Once GTP is bound to the myristoylated protein, it becomes activated, exposing the myristoyl group. These conformational switches can be utilized as a signal for cellular localization, membrane-protein, and protein–protein interactions.[5][13][14]

Dual modifications of myristoylated proteins

Further modifications on N-myristoylated proteins can add another level of regulation for myristoylated protein. Dual acylation can facilitate more tightly regulated protein localization, specifically targeting proteins to lipid rafts at membranes[15] or allowing dissociation of myristoylated proteins from membranes.

Myristoylation and palmitoylation are commonly coupled modifications. Myristoylation alone can promote transient membrane interactions[5] that enable proteins to anchor to membranes but dissociate easily. Further palmitoylation allows for tighter anchoring and slower dissociation from membranes when required by the cell. This specific dual modification is important for G protein-coupled receptor pathways and is referred to as the dual fatty acylation switch.[5][8]

Myristoylation is often followed by phosphorylation of nearby residues. Additional phosphorylation of the same protein can decrease the electrostatic affinity of the myristoylated protein for the membrane, causing translocation of that protein to the cytoplasm following dissociation from the membrane.[5]

Signal transduction

Myristoylation plays a vital role in membrane targeting and signal transduction[16] in plant responses to environmental stress. In addition, in signal transduction via G protein, palmitoylation of the α subunit, prenylation of the γ subunit, and myristoylation is involved in tethering the G protein to the inner surface of the plasma membrane so that the G protein can interact with its receptor.[17]

Apoptosis

Myristoylation is an integral part of apoptosis, or programmed cell death. Apoptosis is necessary for cell homeostasis and occurs when cells are under stress such as hypoxia or DNA damage. Apoptosis can proceed by either mitochondrial or receptor mediated activation. In receptor mediated apoptosis, apoptotic pathways are triggered when the cell binds a death receptor. In one such case, death receptor binding initiates the formation of the death-inducing signaling complex, a complex composed of numerous proteins including several caspases, including caspase 3. Caspase 3 cleaves a number of proteins that are subsequently myristoylated by NMT. The pro-apoptotic BH3-interacting domain death agonist (Bid) is one such protein that once myristoylated, translocates to the mitochondria where it prompts the release of cytochrome c leading to cell death.[8] Actin, gelsolin and p21-activated kinase 2 PAK2 are three other proteins that are myristoylated following cleavage by caspase 3, which leads to either the up-regulation or down-regulation of apoptosis.[8]

Impact on human health

Cancer

c-Src is a gene that codes for proto-oncogene tyrosine-protein kinase Src, a protein important for normal mitotic cycling. It is phosphorylated and dephosphorylated to turn signaling on and off. Proto-oncogene tyrosine-protein kinase Src must be localized to the plasma membrane in order to phosphorylate other downstream targets; myristoylation is responsible for this membrane targeting event. Increased myristoylation of c-Src can lead to enhanced cell proliferation and be responsible for transforming normal cells into cancer cells.[5][14][18] Activation of c-Src can lead to the so-called "hallmarks of cancer", among them upregulation of angiogenesis, proliferation, and invasion.[19]

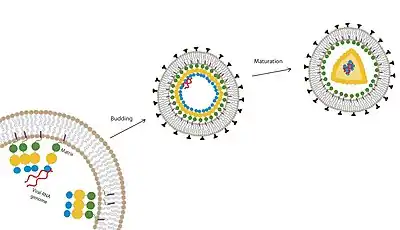

Viral infectivity

HIV-1 is a retrovirus that relies on myristoylation of one of its structural proteins in order to successfully package its genome, assemble and mature into a new infectious particle. Viral matrix protein, the N-terminal–most domain of the gag polyprotein, is myristoylated.[20] This myristoylation modification targets gag to the membrane of the host cell. Utilizing the myristoyl-electrostatic switch,[13] including a basic patch on the matrix protein, gag can assemble at lipid rafts at the plasma membrane for viral assembly, budding and further maturation.[18] In order to prevent viral infectivity, myristoylation of the matrix protein could become a good drug target.

Prokaryotic and eukaryotic infections

Certain NMTs are therapeutic targets for development of drugs against bacterial infections. Myristoylation has been shown to be necessary for the survival of a number of disease-causing fungi, among them C. albicans and C. neoformans. In addition to prokaryotic bacteria, the NMTs of numerous disease-causing eukaryotic organisms have been identified as drug targets as well. Proper NMT functioning in the protozoa Leishmania major and Leishmania donovani (leishmaniasis), Trypanosoma brucei (African sleeping sickness), and P. falciparum (malaria) is necessary for survival of the parasites. Inhibitors of these organisms are under current investigation. A pyrazole sulfonamide inhibitor has been identified that selectively binds T. brucei, competing for the peptide binding site, thus inhibiting enzymatic activity and eliminating the parasite from the bloodstream of mice with African sleeping sickness.[8]

See also

References

- 1 2 Cox, David L. Nelson, Michael M. (2005). Lehninger principles of biochemistry (4th ed.). New York: W.H. Freeman. ISBN 978-0716743392.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - 1 2 Tamanoi, Fuyuhiko; Sigman, David S., eds. (2001). Protein lipidation. Vol. 21 (3rd ed.). San Diego, CA: Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-122722-7.

- ↑ Mohammadzadeh, Fatemeh; Hosseini, Vahid; Mehdizadeh, Amir; Dani, Christian; Darabi, Masoud (2018-11-30). "A method for the gross analysis of global protein acylation by gas-liquid chromatography". IUBMB Life. 71 (3): 340–346. doi:10.1002/iub.1975. ISSN 1521-6543. PMID 30501005.

- ↑ Kara, UA; Stenzel, DJ; Ingram, LT; Bushell, GR; Lopez, JA; Kidson, C (Apr 1988). "Inhibitory monoclonal antibody against a (myristylated) small-molecular-weight antigen from Plasmodium falciparum associated with the parasitophorous vacuole membrane". Infection and Immunity. 56 (4): 903–9. doi:10.1128/IAI.56.4.903-909.1988. PMC 259388. PMID 3278984.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Farazi, T. A. (29 August 2001). "The Biology and Enzymology of Protein N-Myristoylation". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 276 (43): 39501–39504. doi:10.1074/jbc.R100042200. PMID 11527981.

- 1 2 Carr, SA; Biemann, K; Shoji, S; Parmelee, DC; Titani, K (Oct 1982). "N-Tetradecanoyl is the NH2-terminal blocking group of the catalytic subunit of cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase from bovine cardiac muscle". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 79 (20): 6128–31. Bibcode:1982PNAS...79.6128C. doi:10.1073/pnas.79.20.6128. PMC 347072. PMID 6959104.

- 1 2 Aitken, A; Cohen, P; Santikarn, S; Williams, DH; Calder, AG; Smith, A; Klee, CB (Dec 27, 1982). "Identification of the NH2-terminal blocking group of calcineurin B as myristic acid". FEBS Letters. 150 (2): 314–8. doi:10.1016/0014-5793(82)80759-x. PMID 7160476. S2CID 40889752.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Martin, Dale D.O.; Beauchamp, Erwan; Berthiaume, Luc G. (January 2011). "Post-translational myristoylation: Fat matters in cellular life and death". Biochimie. 93 (1): 18–31. doi:10.1016/j.biochi.2010.10.018. PMID 21056615.

- 1 2 Bhatnagar, RS; Fütterer, K; Waksman, G; Gordon, JI (Nov 23, 1999). "The structure of myristoyl-CoA:protein N-myristoyltransferase". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular and Cell Biology of Lipids. 1441 (2–3): 162–72. doi:10.1016/s1388-1981(99)00155-9. PMID 10570244.

- ↑ Snider, Jared. "Overview of Post-Translational Modifications (PTMs)". Thermo Scientific.

- ↑ Chen, Katherine A.; Manning, David R. (2001). "Regulation of G proteins by covalent modification". Oncogene. 20 (13): 1643–1652. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1204185. PMID 11313912.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Doll, Sebastian; Freitas, Florencio Porto; Shah, Ron; Aldrovandi, Maceler; da Silva, Milene Costa; Ingold, Irina; Goya Grocin, Andrea; Xavier da Silva, Thamara Nishida; Panzilius, Elena; Scheel, Christina H.; Mourão, André (November 2019). "FSP1 is a glutathione-independent ferroptosis suppressor". Nature. 575 (7784): 693–698. Bibcode:2019Natur.575..693D. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1707-0. hdl:10044/1/75345. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 31634899. S2CID 204833583.

- 1 2 3 McLaughlin, Stuart; Aderem, Alan (July 1995). "The myristoyl-electrostatic switch: a modulator of reversible protein–membrane interactions". Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 20 (7): 272–276. doi:10.1016/S0968-0004(00)89042-8. PMID 7667880.

- 1 2 Wright, Megan H.; Heal, William P.; Mann, David J.; Tate, Edward W. (7 November 2009). "Protein myristoylation in health and disease". Journal of Chemical Biology. 3 (1): 19–35. doi:10.1007/s12154-009-0032-8. PMC 2816741. PMID 19898886.

- ↑ Levental, Ilya; Grzybek, Michal; Simons, Kai (3 August 2010). "Greasing Their Way: Lipid Modifications Determine Protein Association with Membrane Rafts". Biochemistry. 49 (30): 6305–6316. doi:10.1021/bi100882y. PMID 20583817.

- ↑ HAYASHI, Nobuhiro; TITANI, Koiti (2010). "N-myristoylated proteins, key components in intracellular signal transduction systems enabling rapid and flexible cell responses". Proceedings of the Japan Academy, Series B. 86 (5): 494–508. Bibcode:2010PJAB...86..494H. doi:10.2183/pjab.86.494. PMC 3108300. PMID 20467215.

- ↑ Wall, Mark A.; Coleman, David E.; Lee, Ethan; Iñiguez-Lluhi, Jorge A.; Posner, Bruce A.; Gilman, Alfred G.; Sprang, Stephen R. (December 1995). "The structure of the G protein heterotrimer Giα1β1γ2". Cell. 83 (6): 1047–1058. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(95)90220-1. PMID 8521505.

- 1 2 Shoji, S; Kubota, Y (Feb 1989). "[Function of protein myristoylation in cellular regulation and viral proliferation]". Yakugaku Zasshi. 109 (2): 71–85. doi:10.1248/yakushi1947.109.2_71. PMID 2545855.

- ↑ Hanahan, Douglas; Weinberg, Robert A. (March 2011). "Hallmarks of Cancer: The Next Generation". Cell. 144 (5): 646–674. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. PMID 21376230.

- ↑ Hearps, AC; Jans, DA (Mar 2007). "Regulating the functions of the HIV-1 matrix protein". AIDS Research and Human Retroviruses. 23 (3): 341–6. doi:10.1089/aid.2006.0108. PMID 17411366.