| Εθνικός Κήπος National Gardens | |

|---|---|

| Βασιλικός Κήπος Royal Gardens | |

Interior view | |

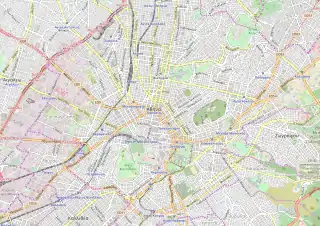

Location within central Athens | |

| Type | Public park |

| Location | Athens, Greece |

| Coordinates | 37°58′27″N 23°44′18″E / 37.97417°N 23.73833°E |

| Area | 15.5 hectares (38 acres) |

| Created | 1838 (184 years ago) |

| Status | Open year round |

| Public transit access | |

The National Garden[1][2] (Greek: Εθνικός Κήπος), called the Royal Garden until 1974,[3] is a public park of 15.5 hectares (38 acres) in the center of the Greek capital, Athens. It is located between the districts of Kolonaki and Pangrati, directly behind the Greek Parliament building (The Old Palace) and continues to the South to the area where the Zappeion is located, across from the Panathenaiko or Kalimarmaro Olympic Stadium of the 1896 Olympic Games. The Garden also encloses some ancient ruins, column drums and Corinthian capitals of columns, mosaics, and other features. On the Southeast side are the busts of Ioannis Kapodistrias, the first governor of Greece, and of the Philhellene Jean-Gabriel Eynard. On the South side are the busts of the celebrated Greek poets Dionysios Solomos, author of the Greek National Hymn, and Aristotelis Valaoritis.

History

The Royal Garden was commissioned by Queen Amalia in 1838 and completed by 1840. It was designed by the German agronomist Friedrich Schmidt who imported over 500 species of plants and a variety of animals including peacocks, ducks, and turtles. Unfortunately for many of the plants, the dry Mediterranean climate proved too harsh and they did not survive. Other botanists planning and managing the garden include Karl Nikolas Fraas, Theodor von Heldreich and Spyridon Miliarakis.

A part of the upper garden, behind the Old Palace, was fenced off and was the private refuge of the King and Queen. The garden was open to the public in the afternoons.

Close to the garden in 1878 the neo-classical Zappeion Hall was built. It was donated by Evangelis Zappas and designed by Theophil Freiherr von Hansen. Zappas had started the Zappian Olympic Games, a precursor to the modern Olympic Games. The Zappeion was the Olympic village for the 1896 Summer Olympics in Athens and also as a venue for the fencing events. Starting in the 1920s, the area in front of the Zappeion was also a major transportation hub for trams and buses. Today it is used for public exhibitions.

The Royal Garden

The Royal Garden was the scene of an unusual turning point in Greek history. In 1920, at the end of World War I, Greece under King Alexander and the government of Eleftherios Venizelos remained committed to the Megali Idea (Greek for The Great Idea) that Greece should gain control of portions of Asia Minor. In 1919, they began the Greco-Turkish War with the support of their former allies Britain and France. While walking in the Garden on September 30, 1920, King Alexander was bitten by a pet monkey (whose pet it is not revealed) and he died of sepsis three weeks later. His death ushered the return of his deposed father, King Constantine I who had been deposed for his pro-German sympathies during the First World War. Upon his return to power, King Constantine assisted in the defeat of his political nemesis, Venizelos in the November 1920 General Election. The new Prime Minister, Dimitrios Gounaris, a monarchist, began replacing the Venezelist military staff with officers more loyal to the new King. As a result of this change in political environment and it is argued, the reduction in military experience by the Army's General Staff, the Allied Powers withdrew their support. The result was the 1922 Great Fire of Smyrna, the defeat of Greek troops in Turkey with exodus of Greek refugees and the 1923 Exchange of populations between Greece and Turkey known collectively by the Greeks as the Asia Minor "Catastrophe. Winston Churchill wrote, "it is perhaps no exaggeration to remark that a quarter of a million persons died of this monkey's bite."[4]

The National Garden

In the 1920s the park was opened to the public and renamed "National Garden". In honour of Amalia of Greece, the entrance was moved to the 12 palms she planted and the street in front was renamed Queen Amalia Avenue. Since then the National Garden, is open to the public from sunrise to sunset.

Henry Miller wrote in 1939:

It remains in my memory like no other park I have known. It is the quintessence of a park, the thing one feels sometimes in looking at a canvas or dreaming of a place one would like to be in and never finds.[5]

In 2004 the Greek state gave the garden for 90 years to the city of Athens.

Ancient ruins

Inside the garden can be spotted ancient ruins, the vast majority of them are Roman. A Roman villa with a mosaic, large numbers of columns of all orders and sizes, structures connected with the Roman baths next to Zappeion and a large marble inscription about Ceaser Aelius ordered by Laius Aettius who was a Roman Legion staff officer from Epirus region and fought in battles against the Germanic tribes can be spotted. [6]

Services

The National Garden, is open to the public from sunrise to sunset. The main entrance is on Leoforos Amalias, the street named after the Queen who envisioned this park. You can also enter the garden from one of three other gates: the central one, on Vasilissis Sophias Avenue, another on Herodou Attikou Street and the third gate connects the National Garden with the Zappeion park area. In the National Garden there are a duck pond, a Botanical Museum, a small cafe and a Children's Library and playground.

Gallery

The Royal Garden c. 1905

The Royal Garden c. 1905 View of the entrance

View of the entrance.jpg.webp) Monument to Lord Byron

Monument to Lord Byron Statue of Ioannis Varvakis

Statue of Ioannis Varvakis Antiquities within the National Garden

Antiquities within the National Garden Ponds in National Garden

Ponds in National Garden

See also

- Greek gardens

- Landscape design history

References

- ↑ "The National Garden". Athens Info Guide , 2004-2009. Retrieved 2010-03-09.

- ↑ "The National Garden, Zappion, Panathenaic Stadium and the Temple of Olympian Zeus". Athens Survival Guide. Retrieved 2010-03-09.

- ↑ "National Garden renamed". Magenta. Retrieved 2021-12-03.

- ↑ Churchill, p. 409, quoted (for example) in Pentzopoulos, p. 39.

- ↑ "National Gardens". Travel to Athens, Greece. Retrieved 2010-03-09.

- ↑ Εθνικός Κηπος και Ιστορία (in Greek). Αθήνα. 2017. pp. 7 to 34.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)