Nazran okrug

Назрановский округ | |

|---|---|

Location in the Terek Oblast | |

| Country | Russian Empire |

| Viceroyalty | Caucasus |

| Oblast | Terek |

| Established | 1905 |

| Abolished | 1924 |

| Capital | Vladikavkaz |

| Area | |

| • Total | 1,526.14 km2 (589.25 sq mi) |

| Population (1916) | |

| • Total | 59,046 |

| • Density | 39/km2 (100/sq mi) |

| • Rural | 100.00% |

The Nazran okrug,[lower-alpha 1] known after March 1917 as the Ingush okrug,[lower-alpha 2] was a district (okrug) of the Terek Oblast of the Caucasus Viceroyalty of the Russian Empire, and after 1921, the Mountain ASSR of the Russian SFSR within the Soviet Union. The district was modest in its population of 59 thousand and size of approximately 1,500 square kilometres (580 sq mi), the smallest of all the Terek Oblast's subdivisions in both measures. The administrative centre of the district was the city of Vladikavkaz.

Due to the Tsarist government's redistribution of land to Cossacks, local peasantry were forced to rent land from the Cossack landowners. As a result of the constant hostilities with the neighbouring Cossacks, the district was formed in 1905 as a separate subdivision for Ingush people. Control of the district passed between the Mountainous Republic of the North Caucasus, the Terek Soviet Republic, and the Armed Forces of South Russia, until finally passing to the control of the Red Army. The area of the Nazran okrug presently corresponds to part of the North Caucasian Federal District of Russia.

According to statistics dated to 1916, the district was almost exclusively populated by North Caucasians—predominantly Ingush—with Russians forming less than 1 percent of the population. The district contained 135 settlements, some of which underwent a series of repressions due to raids by local Ingush outlaws.

History

Establishment

Due to mutual hostility and constant conflicts between Ingush and Cossack peoples, the Russian government was forced to form a separate district for Ingush.[1][2] By a decree of 8 December [O.S. 25 November] 1905,[3] the Ingush populated land, consisting of seventeen plain villages and four mountain societies,[lower-alpha 3] was carved out of the Sunzhensky otdel to temporarily create Nazran okrug. Despite the fact that this territorial reform was intended to solve the immediate practical problem not in favor of the Ingush and with the reform subsequently displacing numerous Ingush farms and entire villages located on lands leased from the Cossacks outside the otdel, the Ingush met this reform with great enthusiasm. The very fact of the restoration of the national-territorial district inspired great hopes, especially since the government itself admitted that the ataman of the Sunzhensky otdel, under whose control the Ingush were previously, due to his military duties, didn't have the opportunity to pay due attention arrangement of civil and economic life of the Ingush population.[4]

Due to the reform being temporary, the local population was worried.[5] In January 1908, elected from the Ingush people, lieutenant Tatre Albogachiev, Shaptuko Kuriev and Duguz Hadzhi Bekov arrived in Tiflis in order to intercede with the Viceroy of Caucasus, Illarion Vorontsov-Dashkov, on "the approval of the temporarily formed Nazran okrug." The request was granted and the Nazran okrug within its specified boundaries was approved on 10 June 1909. The administration of the okrug and the mountain verbal court were established on a common basis with other okrugs of Terek Oblast][6] By a decree of 6 August [O.S. 24 July] 1909, Nazran okrug was deemed permanent.[3]

The seat of the administration of the district was appointed Nazran which, in practice, didn't function as the seat of the administration due to a lack of suitable buildings. Instead, Vladikavkaz was appointed the seat of the administration up until January 1917 by a decree of February 1913 of the State Council and the State Duma.[6][7][8]

Imperial Russian rule

In 1905, the number of manifestations of outright disloyalty of the mountaineers to the administration and its local representatives increased. At meetings of various villages, the Ingush population demanded the return of lands that previously belonged to them which were seized under the control of the state property department. It was during the beginning of December of the same year when more serious clashes between local residents and the authorities in Ingush villages started to happen.[9]

On 23 December 1905, the head of the Nazran okrug Lieutenant Colonel Ya. E. Mitnik was killed during attempt to disarm the highlanders in the village of Barsuki.[10] His murder was a response to the ongoing terror conducted by the Tsarist administration in the okrug.[11] Mitnik's death, along with the railway strike that had been ongoing since 8 December and the Lagir peasant uprising that broke out on 21 December, played a role in the introduction of martial law in the entire Terek Oblast on 23 December.[10]

Furious over the robberies and raids of the abreks Zelimkhan and Sulumbek, Aleksandr Mikheev, together with Ingush tsarist officers, gathered the entire Ingush clergy in Vladikavkaz on 23 September 1910. He spoke to them with insults and announced to them that the Ingush were deprived of the right to use the Cossack lands they leased,[lower-alpha 4] that he was depriving the okrug of the right to elect elders and that he would submit a petition to the viceroy of the Caucasus for the demolition of all Ingush farms and villages of the Assa Gorge. This meant the forceful property seizure from the disadvantaged mountain population. Furthermore, Mikheev began to petition Russian government to organize a punitive expedition to the Ingush mountains, the allowance for which would be entrusted to the Ingush mountaineers, who were already in poverty under the yoke of the military-police regime.[12]

In 1911, as wave of severe repressions swept across the okrug, the villages Koki, Nelkh and Ersh were destroyed. 360 representatives of the Kokurkhoev family, including children, women and old people, were jailed in a Vladikavkaz prison for three months and then exiled to the Yeniseysk Governorate.[12] Fearing an uprising of the mountaineers for independence under the leadership of influential clergy, Russian authorities also exiled prominent spiritual figures[lower-alpha 5] of Chechnya, Ingushetia and Dagestan.[13] According to Lemka Agieva, more than 30 people from among the highest Chechen and Ingush clergy were exiled.[12]

Moreover, the Ingush, Chechens and other mountain peoples were accused of all the mortal sins. For example, the Cossack nationalist Georgy Tkachev published in 1911 the book Ingush and Chechens in the Family of Nationalities of the Terek Region where he justified the Cossack and military-police lawlessness against the Chechens and Ingush, explaining that the reason for the robberies on the part of the mountaineers "lies in the very character of the Ingush–Chechen people".[12]

World War I and Russian Civil War

The outbreak of the World War I dealt another serious blow to the economic situation of the Nazran okrug which was already quite adverse. New military conditions, an increase in old taxes and the introduction of new ones, in fact, an emergency regime further aggravated the economic and political situation of the okrug.[14]

The February Revolution of 1917, which overthrew the Tsarist autocracy, found a wide response by local masses. Already in early March 1918, civil committees were created in the Terek Oblast which served as a local representation of the Russian Provisional Government. By 1 May 1917 National Councils had also been created in individual okrugs of the Terek Oblast, including Nazran okrug,[15] which became known as Ingush okrug from March 1917.[16] The Ingush National Council was headed by Vassan-Girey Dzhabagiev. His brother Magomed Dzhabagiev was the representative of Ingushetia within the Civil Committee in Vladikavkaz, being the latter's commissioner for the okrug.[15]

Soviet rule

The first congress of the Ingush people was held in Nazran on 4 April 1920. It was attended by prominent Bolshevik revolutionaries like Sergo Ordzhonikidze and Sergei Kirov who were welcomed by 15,000 Ingush.[17] The congress ended with the proclamation of the restoration of Soviet power in the Ingush okrug[18] and approval of the composition of the Ingush District Revolutionary Committee, which included Gapur Akhriev, Yusup Albogachiev, Idris Zyazikov and others. After the death of the first chairman of the committee, Gapur Akhriev, the first re-organization took place in April with Albogachiev becoming the next chairman.[17] The Terek Regional Revolutionary created on 8 April 1920 also approved the new composition of the Ingush Revolutionary Committee.[19]

From 26 March to 1 April 1921, the Congress of Soviets of the Ingush okrug was held. Delegates from 28 villages of the okrug were present at the congress. Idris Zyazikov was elected chairman of the executive committee of the congress. Issues of taking measures to combat robberies and banditry were discussed at the congress. It ended with the election of the executive committee, which included Idris Zyazikov, Ali Gorchkhanov, Inaluk Malsagov, Yusup Albogachiev, Sultan Aldiev and others.[20]

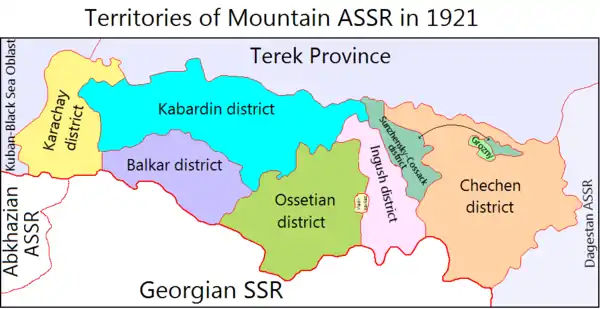

On 21 January 1921, the All-Russian Central Executive Committee issued a decree on the formation of the Mountain Republic on the territory of the former Terek Oblast. Paragraph 8 of the decree read: "The Autonomous Mountain Socialist Soviet Republic is divided into 6 administrative districts, each with its own district executive committee: 1) Chechen; 2) Ingush; 3) Ossetian; 4) Kabardian; 5) Balkar; 6) Karachai."[21] The Congress of Soviets of the Ingush okrug held on 26 March to 1 April 1921 fully approved and welcomed the creation of an autonomous republic. The process of the creation of Mountain ASSR ended on 16–22 April 1921 with the Founding Congress of Soviets of the Republic in Vladikavkaz, which on behalf of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee and the Central Committee of the Russian Communist Party welcomed Sergei Kirov. From Ingush okrug, Idris Zyazikov entered the governing bodies of the ASSR—to the Central Executive Committee as deputy chairman and to the Council of People's Commissars as People's Commissar of Internal Affairs. On 27 January 1922, he was also elected chairman of the Mountain Central Executive Committee.[22]

After the Founding Congress of the GASSR on 22 April 1921 approved the elimination of Cossack stripes due to the strong need of land by mountaineers, the territory of Ingush okrug expanded from 184,438.90 dessiatines to 292,193 dessiatines which made it possible for the majority of residents of the mountainous region to move to the plain. In 1920–1922 the plots of the former Cossack stanitsas of Sunzhenskaya, Vorontsovo-Dashkovskaya, Tarskoye and Kambileevsky farms were distributed between 4 mountain Ingush societies—Dzherakh, Fyappins, Khamkhins and Tsorins.[22]

In May–June 1922, the Extraordinary Commission of the City Central Executive Committee and the Council of People's Commissars of the Mountain ASSR concluded a number of serious shortcomings in the work of the party and Soviet bodies of the Chechen, Digor, Sunzha and Ingush okrugs. The role of the Bolsheviks in Soviet construction was insignificant and there weren't enough experienced party and Soviet workers.[23] Based on the materials of the Extraordinary Commission, the State Central Executive Committee passed a resolution in 13 June 1922 which dissolved the Chechen, Nazran, Digor and Sunzha okrug executive committees and appointed instead revolutionary committees from the most experienced party and Soviet workers, tested in practical work. The revolutionary committees were strengthened by the Bolsheviks.[24]

The zoning of the Mountain ASSR was completed by September 1923.[25] The republic was divided into Ossetian, Ingush and Sunzha okrugs. The Ingush okrug was divided into three raions—Nazran, Psedakh and Galashkin; it included 39 village executive committees.[26]

In May–June 1922, the Extraordinary Commission of the City Central Executive Committee and the Council of People's Commissars of the Mountain ASSR concluded a number of serious shortcomings in the work of the party and Soviet bodies of the Chechen, Digor, Sunzha and Ingush okrugs. The role of the Bolsheviks in Soviet construction was insignificant and there weren't enough experienced party and Soviet workers.[23] Based on the materials of the Extraordinary Commission, the State Central Executive Committee passed a resolution in 13 June 1922 which dissolved the Chechen, Nazran, Digor and Sunzha okrug executive committees and appointed instead revolutionary committees from the most experienced party and Soviet workers, tested in practical work. The revolutionary committees were strengthened by the Bolsheviks.[24]

Economy

Agriculture

Local peasantry were suffering from lack of land. Cossacks being the largest land magnates of the Terek Oblast, owned about a third of the entire territory, despite the so-called military class compromising less than a fifth of the total population of the oblast. The Ingush population was forced to rent land from the Cossacks, paying them a very high price, ranging from 3 to 8.3 rubles. For instance, in the Galashian Gorge, 484 households, of which 1,487 were Ingush men, rented 5,788 acres of land from the Terek Army. Ingush mountain societies annually paid 49,943 rubles for the rental of Cossack and landowner land. In total, there was 8 rubles in rent per capita of the male population.[27]

Despite numerous demands and appeals from the population, the territory of the Nazran okrug never increased and it remained at the size of 2,468.1 square versts (2,808.9 km2; 1,084.5 sq mi). This led to the extreme severity of the problem of land shortage. Peasants had an average of 1.8 dessiatines of land per male soul in the mountainous region and 4 dessiatines in the plain region. Furthermore, the land wasn't always suitable for sowing. For comparison, the Cossacks had 21.3 tithes per capita.[27]

A large number of Ingush farms were completely landless. At the same time, the peasants were pressed by numerous direct and indirect taxes and duties. The groups of Nazran okrug became more and more stratified in a way: at one side there was a wealthy elite—the kulaks, at the other—a mass of landless and land-poor peasants—rural proletarians and semi-proletarians. This stratification, although on a much smaller scale, could also be observed in the mountainous region, where the population lived by renting land and non-agricultural labor.[27]

The rental relations developed especially intensively under the conditions of the Stolypin reform and with the creation of local branches of the Peasants' Land Bank. Before the outbreak of World War I, the purchase and sale of land became widespread. For instance, inhabitants of the Metskhal society like Yandievs, Esmurzievs, Daurbekovs, Bersanovs, Kotievs, Matievs and Zaurovs purchased 1,000 acres of land from the landowner F. Pelipeyko in 1911.[27]

Revenue

The Regulations on Rural (Aul) Societies (1870) regulated the life of the rural population of the Terek Oblast. Based on this regulations, the local Russian administration proceeded opening rural boards and courts, convening assemblies and collecting taxes. The Nazran okrug was subject to state quitrent taxes and land taxes from which the Ingush peasantry suffered. In 1915, state and zemstvo taxes were paid by 49 rural societies and 147 private estates which owned 121,348 and 14,395 acres of land; in total, the state received 78,660 rubles in land tax and quitrent tax from the okrug.[27]

Since the regulations didn't establish the types of taxes and their size, the local administration itself often introduced indirect taxes at will.[28] For example, the villages of Barsuki and Yandare were subject to such taxes like office and repair expenses, a personal tax, a tax in lieu of serving military service, a zemstvo and medical tax, a fee for the maintenance of the Nazran mountain school, policemen and horsemen at the post. Despite the route along the postal route from the station Beslan to the city of Port-Petrovsk (present-day Makhachkala), on the territory of Nazran, having a length of only 22 miles, 258 rubles were collected for the maintenance of the zemstvo post office 54 kopecks from The village of Yandare. For comparison, for the maintenance of a postal route 26 versts (28 km; 17 mi) through Sleptsovskaya (present-day Sunzha), the administration collected only 120 rubles.[29]

The entire rural population of the Nazran okrug bore secular duties to satisfy the internal needs of the peasant community. Based on the regulations of 19 February 1861, these duties were divided into compulsory and optional. In 1911, the compulsory duties of the okrug included: maintenance of the clergy – 924 rubles; maintenance of public administration personnel – 24,984 rubles; road repairs – 6,065 rubles; maintenance of the sanitary and charitable parts – 1,971 rubles. Optional duties of the okrug included: maintenance, construction and repair of schools – 3,532 rubles; construction, repair and rental of various other premises – 3,051 rubles; for various other needs[lower-alpha 6] – 157,558 rubles.[29]

In addition to aforementioned taxes and fees, some targeted Fred were collected from the population. For instance, in 1909, residents of the village Nasyr-Kort requested permission to build a path from the Nazran station to the village of Mikheevsky. They were allowed with the requirement to complete the road project and carry out all earthworks at their own expense, as well as to deposit 24,562 rubles into the cash desk of the Nazran station.[29]

Administrative divisions

The prefectures (участки, uchastki) of the Nazran okrug in 1912 were as follow:[30][31]

| Name | Administrative centre | Population |

|---|---|---|

| First Prefecture (1-й участок) | Psedakh | 15,720 |

| Second Prefecture (2-й участок) | Nazran | 24,982 |

| Third Prefecture (3-й участок) | Vladikavkaz | 13,395 |

The rural communities (сельские общества, selskiye obshchestva) of the okrug in 1917 were as follow:[31]

- Verkhne[lower-alpha 7]-Achalukskoye (Верхне-Ачалукское)

- Nizhne[lower-alpha 8]-Achalukskoye (Нижне-Ачалукское)

- Sredne[lower-alpha 9]-Achalukskoye (Средне-Ачалукское)

- Donakovskoye (Донаковское)

- Kantyshevskoye (Кантышевское)

- Keskemskoye (Кескемское)

- Psedakhskoye (Пседахское)

- Sogopshskoye (Согопшское)

- Altyyevskoye (Алыевское)

- Bursukovskoye (Бурсуковское)

- Gamurziyevskoye (Гамурзиевское)

- Nasyr-Kortovskoye (Насыр-Кортовское)

- Pliyevskoye (Плиевское)

- Surkhokhinskoye (Сурхохинское)

- Ekazhevskoye (Экажевское)

- Yandyrskoye (Яндырское)

- Bazorkinskoye (Базоркинское)

- Dzherakhoyevskoye (Джерахоевское)

- Metskhalskoye (Мецхальское)

- Khamkhinskoye (Хамхинское)

- Tsorinskoye (Цоринское)

Demographics

According to the 1917 publication of Kavkazskiy kalendar, the Nazran okrug had a population of 59,046 on 14 January [O.S. 1 January] 1916, including 31,038 men and 28,008 women, 57,178 of whom were the permanent population, and 1,868 were temporary residents:[32]

| Nationality | Number | % |

|---|---|---|

| North Caucasians | 58,842 | 99.65 |

| Russians | 204 | 0.35 |

| TOTAL | 59,046 | 100.00 |

Settlements

In 1914, the Nazran okrug consisted of the following 135 settlements:[33]

| Settlement | Population | Settlement | Population | Settlement | Population |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abini | 188 | Datykh N.[lower-alpha 8] | 285 | Odzik Sr.[lower-alpha 9] | 33 |

| Agenty | 40 | Dlinnaya-Dolina | 769 | Odzik N.[lower-alpha 8] | 14 |

| Agutyr | 15 | Dokal | 56 | Ozmi V.[lower-alpha 7] | 94 |

| Adsegi | 35 | Dolakovskoye | 2,009 | Ozmi Sr.[lower-alpha 9] | 17 |

| Akabos | 22 | Dugurgidzh | 82 | Ozmi N.[lower-alpha 8] | 25 |

| Alikhochet | 10 | Ersh | 138 | Olget | 50 |

| Alkun | 342 | Kaberakh | 61 | Pamyat | 18 |

| Al'tyyevskoye | 1,123 | Kaylakh | 35 | Pliyevskoye | 2,115 |

| Anty | 14 | Kayrakh | 35 | Psedakh | 1,420 |

| Arzi | 398 | Kantysheva | 3,474 | Puy | 25 |

| Arshtaug | 3 | Kedzi | 20 | Pyaling | 120 |

| Arshty V.[lower-alpha 7] | 148 | Keskem | 1,686 | Sagopsh | 2,412 |

| Achaluk N.[lower-alpha 8] | 3,048 | Kirki | 18 | Salgi | 40 |

| Achaluk V.[lower-alpha 7] | 1,443 | Kirobi | 17 | Sarali-Apiyevo | 107 |

| Achaluk St.[lower-alpha 10] | 1,494 | Koki | 32 | Satkhum | 32 |

| Bazarkino | 4,516 | Koli | 33 | Semiogach | 277 |

| Balkoyevo | 14 | Kort | 70 | Suloy | 78 |

| Bartabos | 264 | Kost’ | 42 | Surkhakhinskoye | 3,230 |

| Barkhin | 47 | Koshet | 61 | Tarsh | 109 |

| Belkhan | 41 | Koshki | 110 | Torgim | 22 |

| Berezhki V.[lower-alpha 7] | 49 | Kyakhk | 18 | Tori | 12 |

| Berezhki Sr.[lower-alpha 9] | 115 | Largebini | 48 | Tumgoy V.[lower-alpha 7] | 34 |

| Biser | 32 | Lelyakh | 88 | Tumgoy N.[lower-alpha 8] | 73 |

| Boyni | 151 | Lyazhki | 198 | Ushkhot | 77 |

| Bosht | 31 | Lyaymi V.[lower-alpha 7] | 17 | Faykhan | 271 |

| Buguzhur | 98 | Lyaymi N.[lower-alpha 8] | 42 | Farapi | 113 |

| Bursukovskoye | 3,006 | Lyashgi | 17 | Fartaug | 127 |

| Vovnushki | 18 | Lyashk | 7 | Khay | 30 |

| Gadaborsh | 9 | Mergisty | 94 | Khayrakh | 25 |

| Gazot | 24 | Metskhal’ | 158 | Khalili | 38 |

| Galashki | 1,655 | Miller | 21 | Khamyshki | 95 |

| Galu | 4 | Moruch | 59 | Khani | 29 |

| Galushki | 25 | Muguchkal | 93 | Khastmak | 14 |

| Gamurziyevskoye | 2,120 | Mudich | 290 | Khulya | 246 |

| Gatstsi | 13 | Mulkum | 16 | Tsizda | 28 |

| Garak | 170 | Musiyevo | 56 | Tsoli | 11 |

| Gaust | 135 | Myashkhi | 59 | Tsori | 145 |

| Gent | 66 | Nazran’ | 350 | Tsorkh | 32 |

| Goyrakh | 84 | Nakist | 20 | Tskheral’ty | 105 |

| Gorosty | 22 | Nasyr-Kort | 4,664 | Shan | 140 |

| Gorkigi | 26 | Nevel’ | 51 | Egochkal | 46 |

| Gu | 13 | Nelkh | 63 | Ekazhevskoye | 3,874 |

| Gul | 120 | Nikota | 16 | Eshkal | 100 |

| Datkhoy-Begach | 24 | Nyy | 86 | Yandyrskoye | 1,847 |

| Datykh V.[lower-alpha 7] | 275 | Odzik V.[lower-alpha 7] | 11 | Yarech | 34 |

Notes

- ↑

- Russian: Назрановский округ, pre-reform orthography: Назрановскій округъ, romanized: Nazranovskiy okrug

- Ingush: Наьсарен окре, romanized: Näsaren okre

- ↑

- Russian: Ингушский округ, pre-reform orthography: Ингушскій округъ, romanized: Ingushskiy okrug

- Ingush: Гӏалгӏай окре, romanized: Ghalghaj okre

- ↑ Dzherakh, Fyappiy, Khamkhins, Tsorins.[4]

- ↑ The Cossack lands they leased were formerly Ingush but were forcibly taken away in favor of the Cossacks.[12]

- ↑ Such as Doku-Sheikh Shaptukaev, Bamat-Girey Hajji Mitaev, Deni Arsanov, Batal Hajji Belkhoroev, Uzun Hajji, Chimmirza, Kanna-Sheikh Khantiev, Sugaip-Mullah Gaisumov, Magomet Hajji Nazirov and Yusup Hajji.[12]

- ↑ Fees that peasant societies could establish for the establishment of rural schools, maintenance of teachers and similar needs. In order for the fees to be established, verdicts needed drawn up with the consent of at least 2/3 of all peasants having the right to vote at the assembly.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 'Upper' in Russian.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 'Lower' in Russian.

- 1 2 3 4 'Middle' in Russian.

- ↑ 'Station' in Russian.

References

- ↑ Shnirelman 2006, p. 42.

- ↑ Tsutsiev 2014, p. 36.

- 1 2 Volkhonskiy 2016.

- 1 2 Dolgieva et al. 2013, p. 23.

- ↑ Albogachieva 2015, p. 186.

- 1 2 Albogachieva 2015, p. 187.

- ↑ Кавказский календарь на 1911 год, col. 180.

- ↑ Marshall 2010, p. 27.

- ↑ Matiev 2011a, p. 134.

- 1 2 Matiev 2011a, p. 135.

- ↑ Gritsenko 1971, p. 72.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Dudarov 2017, p. 14.

- ↑ Daudov & Meskhidze 2009, p. 26.

- ↑ Matiev & Muzhukhoeva 2013, p. 65.

- 1 2 Matiev & Muzhukhoeva 2013, p. 67.

- ↑ Ugurchieva 2006, Заключение.

- 1 2 Dolgieva et al. 2013, p. 437.

- ↑ Mukhanov 2020.

- ↑ Dolgieva et al. 2013, p. 437–438.

- ↑ Dolgieva et al. 2013, p. 439.

- ↑ Dolgieva et al. 2013, p. 439–440.

- 1 2 Dolgieva et al. 2013, p. 440.

- 1 2 Daudov & Meskhidze 2009, p. 136.

- 1 2 Daudov & Meskhidze 2009, p. 137.

- ↑ Daudov & Meskhidze 2009, p. 140.

- ↑ Daudov & Meskhidze 2009, p. 141.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Dzumatova 2017, p. 62.

- ↑ Dzumatova 2017, p. 62–63.

- 1 2 3 Dzumatova 2017, p. 63.

- ↑ Кавказский календарь на 1913 год, pp. 186–187.

- 1 2 Кавказский календарь на 1917 год, pp. 166–168.

- ↑ Кавказский календарь на 1917 год, pp. 226–237.

- ↑ Кавказский календарь на 1915 год, pp. 82–214.

Bibliography

English sources

- Marshall, Alex (September 13, 2010). The Caucasus Under Soviet Rule (PDF). Routledge Studies in the History of Russia and Eastern Europe. Abingdon-on-Thames: Routledge. ISBN 9781136938252.

- Meskhidze, J. I. (March–June 2006). "Shaykh Batal Hajji from Surkhokhi: towards the history of Islam in Ingushetia" (PDF). Central Asian Survey. Routledge. 25 (1–2): 179–181. doi:10.1080/02634930600903262. eISSN 1465-3354. ISSN 0263-4937.

- Tsutsiev, Arthur (2014). Atlas of the Ethno-Political History of the Caucasus (PDF). Translated by Nora Seligman Favorov. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300153088. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 June 2023.

Russian sources

- Albogachieva, Makka (2015). "Демаркация границ Ингушетии" [Demarcation of the borders of Ingushetia] (PDF). In Karpov, Yuriy (ed.). Горы и границы: Этнография посттрадиционных обществ [Mountains and Borders: An Ethnography of Post-Traditional Societies] (in Russian). SPb.: Kunstkamera. pp. 168–255. ISBN 978-5-88431-290-6. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-10-10.

- Daudov, Аbdulla; Meskhidze, Julietta (2009). Komissarova, Irina (ed.). Национальная государственность горских народов Северного Кавказа (1917—1924) [National statehood of the mountain peoples of the North Caucasus (1917-1924)] (in Russian). SPb.: SPSU. pp. 1–223.

- Dolgieva, Maryam; Kartoev, Magomet; Kodzoev, Nurdin; Matiev, Timur (2013). Kodzoev, Nurdin; et al. (eds.). История Ингушетии [History of Ingushetia] (4th ed.). Rostov-Na-Donu: Yuzhnyy izdatelsky dom. pp. 1–600. ISBN 978-5-98864-056-1.

- Dudarov, Abdul-Mazhit (2017). "Горцы и духовенство Северного Кавказа при смене двух империй — царской и большевистской" [Highlanders and clergy of the North Caucasus with the change of two empires - Tsarist and Bolshevik]. Vestnik INIIGN im. Ch. E. Akhrieva (in Russian). Magas: INIIGN im. Ch. E. Akhrieva (2): 10–16.

- Dzumatova, Zareta (2017). "К вопросу об экономическом развитии Назрановского (Ингушского) округа в начале XX века" [On the issue of economic development of the Nazran (Ingush) district at the beginning of the 20th century]. Sovremennaya nauchnaya mysl (in Russian) (3): 61–67.

- Gritsenko, Nikolai (1971). Классовая борьба крестьян в чечено-ингушетии на рубеже XIX-XX веков [The class struggle of peasants in Chechen-Ingushetia at the turn of the 19th-20th centuries] (in Russian). Grozny: ChIKI. pp. 1–108.

- Кавказский календарь на 1911 год [Caucasus calendar for 1911] (in Russian) (66th ed.). Tiflis: Tipografiya kantselyarii Ye.I.V. na Kavkaze, kazenny dom. 1911. Archived from the original on 31 January 2022.

- Кавказский календарь на 1913 год [Caucasian calendar for 1913] (in Russian) (68th ed.). Tiflis: Tipografiya kantselyarii Ye.I.V. na Kavkaze, kazenny dom. 1913. Archived from the original on 19 April 2022.

- Кавказский календарь на 1915 год [Caucasian calendar for 1915] (in Russian) (70th ed.). Tiflis: Tipografiya kantselyarii Ye.I.V. na Kavkaze, kazenny dom. 1915. Archived from the original on 4 November 2021.

- Кавказский календарь на 1917 год [Caucasian calendar for 1917] (in Russian) (72nd ed.). Tiflis: Tipografiya kantselyarii Ye.I.V. na Kavkaze, kazenny dom. 1917. Archived from the original on 4 November 2021.

- Matiev, Timur (2011). "Меры царской администрации по подавлению движений социального протеста в Ингушетии в 1905—1907 гг." [Measures of the tsarist administration suppression of social protest movements in Ingushetia in 1905–1907]. Vlast (in Russian) (9): 133–135. ISSN 2071-5358.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Matiev, Timur (2011). "Режим военного управления Ингушетии в период нахождения на ее территории Добровольческой армии в 1919—1920 гг." [The regime of military administration of Ingushetia during the period of the presence of the Volunteer Army on its territory in 1919–1920]. Vlast (in Russian) (12): 180–182. ISSN 2071-5358.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Matiev, Timur; Muzhukhoeva, Elza (2013). "Социально-политическое развитие в XIX—начале XX века" [Socio-political development in the 19th - early 20th centuries]. In Albogachieva, Makka; Martazanov, Arsamak; Solovyeva, Lyubov (eds.). Ингуши [The Ingush]. Narody I kultury (in Russian). Moscow: Nauka. pp. 58–69. ISBN 978-5-02-038042-4.

- Mukhanov, Vadim (2020) [2012]. "НАЗРА́НЬ" [Nazrán]. Great Russian Encyclopedia (in Russian). Moscow: Great Russian Encyclopedia.

- Shnirelman, Victor (2006). Kalinin, Ilya (ed.). Быть Аланами: Интеллектуалы и политика на Северном Кавказе в XX веке [To be Alans: Intellectuals and Politics in the North Caucasus in the 20th Cenury] (in Russian). Moscow: NLO. pp. 1–348. ISBN 5-86793-406-3. ISSN 1813-6583.

- Ugurchieva, Khava (2006). Назрановский (Ингушский) округ: этапы образования, становления и развития (1905—1921 гг.): 1905—1921 гг. [Nazran (Ingush) okrug: stages of formation, formation and development (1905–1921): 1905–1921.] (in Russian). Moscow.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Volkhonskiy, Mikhail (2016). "ТЕ́РСКАЯ О́БЛАСТЬ" [Terek Oblast]. In Kravets, Sergei; et al. (eds.). Great Russian Encyclopedia (in Russian). Vol. 32: Televizionnaya bashnya - Ulan-Bator. Moscow: Great Russian Encyclopedia. ISBN 978-5-85270-369-9.

.jpg.webp)