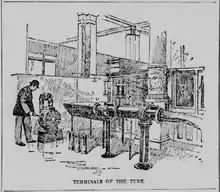

The pneumatic tube mail was a postal system operating in New York City from 1897 to 1953 using pneumatic tubes. Similar systems had arisen in the mid-19th century in London, via the London Pneumatic Despatch Company; in Manchester and other British cities; and in Paris via the Paris pneumatic post. Following the creation of the first American pneumatic mail system in Philadelphia in 1893, New York City's system was begun, initially only between the old General Post Office on Park Row and the Produce Exchange on Bowling Green, a distance of 3,750 feet (1,140 m).[1][2]

Eventually the network stretched up both sides of Manhattan Island all the way to Manhattanville on the West side and "Triborough" in East Harlem, forming a loop running a few feet below street level. Travel time from the General Post Office to Harlem was 20 minutes. A crosstown line connected the two parallel lines between the new General Post office on the West Side and Grand Central Terminal on the east, and took four minutes for mail to traverse. Using the Brooklyn Bridge, a spur line also ran from Church Street, in lower Manhattan, to the general post office in Brooklyn (now Cadman Plaza), taking four minutes.[1] Operators of the system were called "Rocketeers".[3]

Though 10 cities were funded for pneumatic-mail, the New York operation was developed the most. By 1907 contracts were issued in five other cities (Boston, Brooklyn, Chicago, Philadelphia, St. Louis), but not in four cities (Baltimore, Cincinnati, Kansas City, San Francisco).[2] The system was discontinued in 1953.

Inauguration

The system was inaugurated on 7 October 1897 and presided over by Senator Chauncey M. Depew who declared,

This is the age of speed. Everything that makes for speed contributes to happiness and is a distinct gain to civilization. We are ahead of the old countries in almost every respect, but we have been behind in methods of communication within our cities. In New York this condition of communication has hitherto been barbarous. If the Greater New York is to be a success, quick communication is absolutely necessary. I hope this system we have seen tried here to-day will soon be extended over all the Greater New York."[4]

The first dispatch was sent by Depew from the General Post Office to the Produce Exchange Post Office and included a bible wrapped in an American flag, a copy of the Constitution, a copy of President William McKinley's inaugural speech and several other papers. The bible was included in order to reference Job 9:25, "Now my days are swifter than a post" (KJV).[4] The return delivery contained a bouquet of violets and, as reported the following day in The New York Times, the round trip took less than three minutes, most of which was taken in unloading and reloading the canister at the other end.[4] Subsequent deliveries included a variety of amusing items including a large artificial peach (a reference to Depew's nickname), clothing, a candlestick and a live black cat.[1][4][5] In his autobiography, postal supervisor Howard Wallace Connelly recalled,

How it could live after being shot at terrific speed from Station P in the Produce Exchange Building, making several turns before reaching Broadway and Park Row, I cannot conceive, but it did. It seemed to be dazed for a minute or two but started to run and was quickly secured and placed in a basket that had been provided for that purpose. A suit of clothes was the third arrival and then came letters, papers, and other ordinary mail matter.[6][7]

The installation in the Borough of Manhattan was constructed by the Tubular Dispatch Company. This company was purchased by the New York Pneumatic Service Company, who continued to operate the tubes under contract to the postal service. Construction after 1902, starting with the line between the New York and the Brooklyn general post offices, was completed by the New York Mail and Newspaper Transportation Company. Stock in these companies was owned entirely by the American Pneumatic Service Company.[8]

Issues

Government studies later argued the mail could be handled at less cost and more expeditiously by other means. The growing volume of mail, limited system capacities, and the advent of the automobile made the tubes "practically obsolete," and actually hindered the efficient operation of the postal service. The pneumatic tube companies vehemently attacked the studies, but subsequent investigation identified that any errors actually favored the tubes. It was further argued that, if the tubes were truly successful, they would have seen wider adoption by the commercial industry.[9][10]

Breakdowns often required digging up streets to retrieve clogged mail and restore the system to operation. At least one death was reported when a test run caused a tube to rupture violently, injuring the repair crew who had dug out a section under 4th Avenue to mend a break in the line.[11]

Closure

The service was suspended during World War I to conserve funding for the war effort.[12] The annual rental payment of $17,000 per mile was considered exorbitant, particularly when compared to the cost of delivery by automobile.[13]

The Brooklyn section alone cost $14,000 in rent per year and $6,200 in labor.[14] After successful lobbying by contractors the service was restored in 1922. Service was again halted between Brooklyn and Manhattan in April 1950 for repairs on the Brooklyn side and was never restored. In 1953 service was halted for the rest of the system, pending review, and was not restored.[14]

Statistics

Each canister could hold 600 letters and would travel up to 35 miles per hour.[12] At the peak, the system carried 95,000 letters a day, representing 30% of all mail in the city.[5] The total system comprised 27 miles (43 km) of tubes, connecting 23 post offices.[1] The canisters used were 25-pound steel cylinders that were either 21 inches long and 7 inches in diameter[5] or 24 inches long and 8 inches in diameter.[1]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Young, Michelle (15 March 2013). "Then & Now: NYC's Pneumatic Tube Mail Network". Untapped Cities: Urban discovery from a New York perspective. Retrieved 17 October 2013.

- 1 2 United States. Congress. Joint Commission to Investigate the Pneumatic-Tube Mail Service (1917). Development of the Pneumatic-tube and Automobile Mail Service: Excerpts from Reports of the Postmasters General and Their Assistants to Congress ; Various Departmental and Congressional Commission Reports, Including Certain Testimony, and Sundry Exhibits Relative to the Pneumatic-tube and Automobile Mail Service. U.S. Government Printing Office.

- ↑ Garber, Megan (13 August 2013). "That Time People Sent a Cat Through the Mail Using Pneumatic Tubes". The Atlantic. Retrieved 18 October 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 "Mail Tube is a Success". The New York Times. 8 October 1897.

- 1 2 3 "1897: The Cat that Christened the New York City Post Office Pneumatic Mail Tubes". The French Hatching Cat: Unusual Animal Tales of Old New York. 10 March 2013. Retrieved 17 October 2013.

- ↑ Connelly, Howard Wallace (1931). Fifty-six Years in the New York Post Office: A Human Interest Story of Real Happenings in the Postal Service. C.J. O'Brien.

- ↑ B.P. "First Pneumatic Mail Delivery In New York 1897". Stuff Nobody Cares About. Retrieved 17 October 2013.

- ↑ United States Post Office Department (1909). Investigations as to Pneumatic-tube Service for the Mails. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. pp. 36–37. Retrieved 8 June 2015.

- ↑ "Wilson Vetoes; Mail Tubes Go". The Sun. New York, NY. June 30, 1918. p. 1. Retrieved 7 April 2016.

- ↑ Annual Report of the Postmaster General. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. 1918. pp. 19–22. Retrieved 8 June 2015.

- ↑ "Killed by Mail Tube". New-York Tribune. New York, NY. February 15, 1903. p. 1. Retrieved 8 June 2015.

- 1 2 "Pneumatic Tube Mail". National Postal Museum. Archived from the original on 23 November 2021. Retrieved 13 April 2022.

- ↑ Ascher, Kate (2007). The Works: Anatomy of a City. New York: Penguin Press. ISBN 9780143112709. cited in Young

- 1 2 Pope, Nancy. "Pneumatic Post". Former Object of the Month. National Postal Museum. Archived from the original on 11 December 2011. Retrieved 17 October 2013.