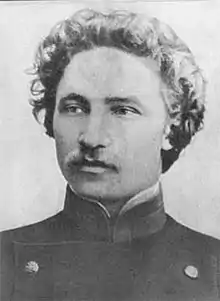

Nikolai Podvoisky | |

|---|---|

| Николай Подвойский | |

| |

| People's Commissar of Military and Naval Affairs of the Russian SFSR | |

| In office 8 November 1917 – 13 March 1918 | |

| Preceded by | Position established (Aleksander Verkhovsky as minister of War and Navy) |

| Succeeded by | Leon Trotsky |

| People's Commissar of Military Affairs of the Ukrainian SSR | |

| In office February 1919 – August 1919 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | February 4 (16), 1880 Nezhinsky Uyezd, Chernigov Governorate, Imperial Russia |

| Died | July 28, 1948 (aged 68) Soviet Union |

| Resting place | Novodevichy Cemetery, Moscow |

| Political party | RSDLP (1901–1903) RSDLP (Bolsheviks) (1903–1918) Russian Communist Party (1918–1935) |

| Signature | |

Nikolai Ilyich Podvoisky (Russian: Николай Ильич Подвойский; Ukrainian: Микола Ілліч Подвойський; February 16 [O.S. February 4], 1880 – July 28, 1948) was a Russian Bolshevik revolutionary, Soviet statesman and the first People's Commissar of Military and Naval Affairs of the Russian SFSR.

He played a large role in the Russian Revolution of 1917 and wrote many articles for the Soviet newspaper Krasnaya Gazeta. He also wrote a history of the Bolshevik Revolution, which describes progress of the Russian Revolution.

Early life

Nikolai Podvoisky was born in Kunochevsk village in the Chernihiv (formerly Chernigov) province, in to a Ukrainian family, one of seven children of a former teacher who had become a priest. In 1901, he was expelled from Chernigov Seminary for political activities. In that same year, he enrolled in the Law Faculty in Yaroslavl, and joined the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP), using the alias 'Mironovich'. After the RSDLP split in 1903, he became a leading figure in the Bolshevik organisation in Yaroslavl. He was arrested in 1904 and again in 1905, for helping organise a strike by the city's railway workers, but soon released on both occasions. Injured during a demonstration, he sought treatment in Germany and Switzerland. He returned to Russia in 1906, and worked illegally as Bolshevik organiser in St. Petersburg, Kostroma, and Baku. In 1913, he settled near St. Petersburg to organise the smuggling of Bolshevik literature into Russia. He was arrested in November 1916, but released during the February Revolution.[1]

Revolution and civil war

In March 1917, Podvoisky was co-opted onto the Petrograd (St. Petersburg) Bolshevik committee, and was appointed head of the Bolshevik Military Organisation. This organisation played a critical role during the disturbances that threatened to bring down Russia's Provisional Government in July 1917.

Leon Trotsky acknowledged that "under Podvoisky, who easily mastered the functions of command, an impromptu general staff was formed...In order to protect the demonstration from attack, armoured cars were placed at the bridges leading to the capital and at the central crossings of the main streets."[2] After the demonstrations were suppressed, Podvoisky — according to Trotsky — veered from being "too impetuous" to becoming "far more cautious",[3] but despite his scepticism played a leading part in the military operation that overthrew the Provisional Government in November 1917, including planning the final act that brought down the government, the assault on the Winter Palace.

Later career

Immediately following the Bolshevik Revolution in November 1917, Podvoisky was one of a troika, with Nikolai Krylenko and Pavel Dybenko appointed People's Commissar for Defence, before they were replaced by Trotsky, in March 1918. He was a founder of the Red Army, but was not an important military commander. He rapidly lost influence during the civil war, part of which he spent in Ukraine. At the tenth party congress of the Russian Communist Party, in March 1920, he proposed that the army should be demobilised and replaced by a localised militia system, a proposal that received no notable support.[4]

In 1920, Podvoisky was appointed Chairman of the Supreme Council of Physical Culture, which ran the system of compulsory physical training of youths prior to their being called up for military service. In July 1921, during the third Comintern congress, in Moscow, he founded the Red Sport International (Sportintern), whose task, according to him, was to "convert sport and gymnastics into a weapon of the class revolutionary struggle, concentrate attention of workers and peasants on sport and gymnastics as one of the best instruments, method and weapons for their class organisation and struggle."[5]

He lost the chairmanship of the Supreme Council of Physical Culture when he was replaced by Nikolai Semashko in 1923, and by 1926 he had lost effective control of Sportintern to the head of the Communist Youth International, Vissarion Lominadze.[6] In 1924-30, Podvoisky was a member of the Central Control Commission, and a reliable supporter of Joseph Stalin against Trotsky and other oppositionists.

From 1935 he was retired and was a personal pensioner. He was engaged in propaganda, literary and journalistic activities for the remainder of his life.

In October 1941, after he was not accepted for military service because of his age, Podvoisky volunteered to lead the digging of trenches near Moscow.[7]

On July 28, 1948, Nikolai Podvoisky died of a severe heart attack in Moscow. He was buried with military honors in Moscow at the Novodevichy cemetery.

Advising Eisenstein

In 1927, Podvoisky was the leading consultant on the film October, directed by Sergei Eisenstein, to mark the tenth anniversary of the October revolution. He helped Eisenstein to find suitable locations in Leningrad, and told him: "You know how stubborn I am, you'd better not argue with me! Better listen to me, and then later don't do it. But make a note of everything I say so that I have the impression I'm being listened to."[8]

On Nudity

Podvoisky was also the foremost Soviet exponent of nudity. He wrote:

almost all parts of your body could easily be left naked for most of the year...We can — and must — discard all the ballast that separates our body from the sun: coats, jackets, vests, shirts, women's fashions, socks, and boots. Nine times out of ten, people wear them not because they need them, but because they want to show off... It is very easy to imagine a perfectly natural setting in which a high-ranking official might appear in public in only his under wear.[9]

He continued writing on sport and as a party historian until he retired on health grounds in 1935.

Personality

By the time Trotsky wrote his history of the Bolshevik revolution, Podvoisky had joined his enemies, yet Trotsky wrote about him more respectfully than about many of the others who went on to join Stalin's faction.

Podvoisky was a sharply outlined and unique figure in the ranks of Bolshevism, with traits of the Russian revolutionary of the old type — from the theological seminaries — a man of great although undisciplined energy, with a creative imagination which, it must be confessed, often went to the length of fantasy. The word 'Podvoiskyism' subsequently acquired on the lips of Lenin a friendly-ironical and admonitory flavour. But the weaker sides of this ebullient nature were to show themselves chiefly after the conquest of power, when an abundance of opportunities and means gave too many stimuli to the extravagant energy of Podvoisky and his passion for decorative undertakings. In the conditions of the revolutionary struggle for power, his optimistic decisiveness of character, his self-abnegation, his tirelessness, made him an irreplaceable leader.[10]

Family

Podvoisky married Nina Didrikil (1882–1953), an Old Bolshevik, who worked at the Lenin Institute, preparing Lenin's manuscript for publication. One of her sisters married the Chekist, Mikhail Kedrov; the other was mother of another chekist, Artur Artuzov. They had five daughters, one of whom, Nina, married Andrei Sverdlov, son of the high ranking Bolshevik Yakov Sverdlov, and a son, Lev, who married the daughter of the Bolshevik Solomon Lozovsky.[11]

References

- ↑ Haupt, Georges; Marie, Jean-Jacques (1974). Makers of the Russian Revolution: Biographies of Bolshevik Leaders. London: George Allen & Unwin. pp. 189–190. ISBN 0-04-947021-3.

- ↑ Trotsky, Leon (1967). History of the Russian Revolution, volume two. London: Sphere. pp. 43–44.

- ↑ Trotsky (1967). History of the Russian Revolution, volume three. p. 277.

- ↑ Carr, E.H. (1970). Socialism in One Country, 1924-1926, volume two. London: Penguin. p. 406.

- ↑ Carr, E.H. (1972). Socialism in One Country, volume 3. London: Penguin. p. 1002.

- ↑ Carr. Socialism in One Country, volume 3. p. 1004.

- ↑ "Пронин Василий Прохорович - Вспом. Предс. Моссовета | Репортаж". reportage.su. Retrieved 2021-11-15.

- ↑ Bergan, Ronald (1999). Sergei Eisenstein, A Life in Conflict. New York: The Overlook Press. p. 128. ISBN 0-87951-924-X.

- ↑ Slezkine, Yuri (2019). The House of Government, A Saga of the Russian Revolution. Princeton: Princeton U.P. pp. 237–38. ISBN 9780691192727.

- ↑ Trotsky. History of the Russian Revolution, volume two. p. 43.

- ↑ Slezkine. The House of Government. pp. 234–35.