Nîmes

Nimes (Occitan) | |

|---|---|

Prefecture and commune | |

.jpg.webp)  _(46785244294).jpg.webp) From top to bottom, left to right: city view from Tour Magne, Fontaine Pradier, Arena of Nîmes and Maison Carrée at night | |

.svg.png.webp) Coat of arms | |

Location of Nîmes | |

Nîmes  Nîmes | |

| Coordinates: 43°50′18″N 04°21′35″E / 43.83833°N 4.35972°E | |

| Country | France |

| Region | Occitania |

| Department | Gard |

| Arrondissement | Nîmes |

| Canton | Nîmes-1, 2, 3 and 4 and Saint-Gilles |

| Intercommunality | CA Nîmes Métropole |

| Government | |

| • Mayor (2020–2026) | Jean-Paul Fournier[1] (LR) |

| Area 1 | 161.85 km2 (62.49 sq mi) |

| Population | 148,104 |

| • Density | 920/km2 (2,400/sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) | Nîmois (masculine) Nîmoise (feminine) |

| Time zone | UTC+01:00 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+02:00 (CEST) |

| INSEE/Postal code | 30189 /30000 and 30900 |

| Elevation | 21–215 m (69–705 ft) (avg. 39 m or 128 ft) |

| 1 French Land Register data, which excludes lakes, ponds, glaciers > 1 km2 (0.386 sq mi or 247 acres) and river estuaries. | |

Nîmes (/niːm/ NEEM, French: [nim] ⓘ; Occitan: Nimes [ˈnimes]; Latin: Nemausus) is the prefecture of the Gard department in the Occitanie region of Southern France. Located between the Mediterranean Sea and the Cévennes, the commune of Nîmes has an estimated population of 148,561 in (2019).[3]

Dubbed the most Roman city outside Italy,[4] Nîmes has a rich history dating back to the Roman Empire when the city had a population of 50,000–60,000 and was the regional capital.[5][6][7][8] Several famous monuments are in Nîmes, such as the Arena of Nîmes and the Maison Carrée. Because of this, Nîmes is often referred to as the "French Rome".

Origins

Nimes is situated where the alluvial plain of the Vistrenque River abuts the hills of Mont Duplan to the northeast, Montaury to the southwest, and to the west Mt. Cavalier and the knoll of Canteduc.

Its name appears in inscriptions in Gaulish as dede matrebo Namausikabo ("he has given to the mothers of Nîmes") and "toutios Namausatis" ("citizen of Nîmes").[9][10]

Nemausus was the god of the local Volcae Arecomici tribe.

History

4000–2000 BCE

The Neolithic site of Serre Paradis reveals the presence of semi-nomadic cultivators in the period 4000 to 3500 BCE on the site of Nîmes.

The menhir of Courbessac (or La Poudrière) stands in a field, near the aerodrome. This limestone monolith of over two metres in height dates to about 2500 BCE, and is considered the oldest monument of Nîmes.

1800–600 BCE

The Bronze Age has left traces of villages that were made out of huts and branches. The population of the site increased during the Bronze Age.

600–121 BCE

The hill of Mt. Cavalier was the site of the early oppidum which gave birth to the city. During the third and 2nd centuries BCE a surrounding wall was built with a dry-stone tower at the summit which was later incorporated into the Tour Magne.

Strabo, the Greek geographer, mentioned that this town functioned as the regional capital for the Volcae Arecomici, a Celtic people. The city adopted the name of a local water deity, Nemausus. The town had a healing spring.[11]

The Warrior of Grezan is considered to be the most ancient indigenous sculpture in southern Gaul.[12]

In 123 BCE the Roman general Quintus Fabius Maximus campaigned against Gallic tribes in the area and defeated the Allobroges and the Arverni, while the Volcae offered no resistance. The Roman province Gallia Transalpina was established in 121 BCE[13] and from 118 BCE the Via Domitia was built through the later site of the city.

Roman period

Amphitheatre used today for concerts and bullfights

Amphitheatre used today for concerts and bullfights Amphiteatre Interior

Amphiteatre Interior Temple of Diana

Temple of Diana.jpg.webp) Roman temple, the "Maison Carrée"

Roman temple, the "Maison Carrée" Roman wall foundations

Roman wall foundations The Augustan Gate

The Augustan Gate

The city arose on the important Via Domitia which connected Italy with Hispania.

Nîmes became a Roman colony as Colonia Nemausus sometime before 28 BCE, as witnessed by the earliest coins, which bear the abbreviation NEM. COL, "Colony of Nemausus".[14] Veterans of Julius Caesar's legions in his Nile campaigns were given plots of land to cultivate on the plain of Nîmes.[15]

Augustus started a major building program in the city, as elsewhere in the empire. He also gave the town a ring of ramparts 6 km (3.7 miles) long, reinforced by 14 towers; two gates remain today: the Porta Augusta and the Porte de France. Internally, the city was organized around the cardo and decumanus, intersecting at the forum. The Maison Carrée, an exceptionally well-preserved temple dating from the late 1st century BCE, stands as one of the finest surviving examples of Roman temple architecture. Dedicated to Roma and Augustus, it bears striking resemblance to Rome's Temple of Portunus, blending Etruscan and Greek design influences.[11]

The great Nimes Aqueduct, many of whose remains can be seen today outside of the city, was built to bring water from the hills to the north. Where it crossed the river Gard between Uzès and Remoulins, the spectacular Pont du Gard was built. This is 20 km (12 mi) north east of the city.

The museum contains many fine objects including mosaic floors, frescoes and sculpture from rich houses and buildings found in excavations in and near the city. It is known that the town had a civil basilica, a curia, a gymnasium and perhaps a circus. The amphitheatre is very well preserved, dates from the end of the 2nd century and was one of the largest amphitheatres in the Empire. The so-called Temple of Diana dating from Augustus and rebuilt in the 2nd century was not a temple but was centred on a nymphaeum located within the Fontaine Sanctuary dedicated to Augustus and may have been a library.

The city was the birthplace of the family of emperor Antoninus Pius (138-161).

Emperor Constantine (306-337) endowed the city with baths.

It became the seat of the Diocesan Vicar, the chief administrative officer of southern Gaul.

The town was prosperous until the end of the 3rd century when successive barbarian invasions slowed its development. During the 4th and 5th centuries, the nearby town of Arles enjoyed more prosperity. In the early 5th century the Praetorian Prefecture was moved from Trier in northeast Gaul to Arles.

The Visigoths captured the city in 472.

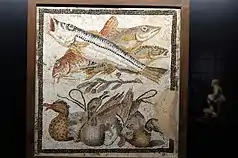

- Finds from Roman Nimes in the Musée de la Romanité

Mosaic of Europa and Zeus

Mosaic of Europa and Zeus Mosaic of still life

Mosaic of still life Pentheus mosaic

Pentheus mosaic Fresco of war galleys

Fresco of war galleys

4th–13th centuries

Obverse: Back to back head of Agrippa left wearing rostral crown, and laureate head of Augustus right; on either side, inscription. Above and below, inscription. Border of dots. Lettering: "IMP P P DIVI F" ("IMPerator DIVI Filius Pater Patriæ", Emperor, Son of the Divine Father of the Nation).

Reverse: Crocodile to right, chained by neck to a palm-tree with tip bending left, two short palms on either side of trunk; on right, inscription; on left, inscription surmounted by a crown with two long tails to right. Border of dots. Lettering: "COL NEM" ("Colonia Nemausus", Colony of Nemausus)When the Visigoths were accepted into the Roman Empire, Nîmes was included in their territory in 472, even after the Frankish victory at the Battle of Vouillé (507). The urban landscape went through transformation with the Goths, but much of the heritage of the Roman era remained largely intact.

By 725, the Muslim Umayyads had conquered the whole Visigothic territory of Septimania including Nîmes. In 736–737, Charles Martel and his brother led an expedition to Septimania and Provence, and largely destroyed the city (in the hands of Umayyads allied with the local Gallo-Roman and Gothic nobility), including the amphitheatre, thereafter heading back north. The Muslim government came to an end in 752, when Pepin the Short captured the city. In 754, an uprising took place against the Carolingian king, but was put down, and count Radulf, a Frank, appointed as master of the city. After the events connected with the war, Nîmes was now only a shadow of the opulent Roman city it had once been. The local authorities installed themselves in the remains of the amphitheatre. Islamic burials have been found in Nîmes.[16][17][18][19]

Carolingian rule brought relative peace, but feudal times in the 12th century brought local troubles, which lasted until the days of St. Louis. During that period Nîmes was jointly administered by a bishop, as well as by a civil authority headquartered in the old amphitheater, where lived the Magistrate/ Viguier, as well as the Viguier's retainers, the Knights of the Arena. Meanwhile the city was represented by four Consuls, whose offices were located in the old Maison Carrée.

Despite incessant feudal squabbling, Nîmes saw some progress both in commerce and industry as well as in stock-breeding and associated activities. After the last effort by Raymond VII of Toulouse, St. Louis managed to establish royal power in the region which became Languedoc. Nîmes thus finally came into the hands of the King of France.

Period of invasions

During the 14th and 15th centuries the Rhone Valley underwent an uninterrupted series of invasions which ruined the economy and caused famine. Customs were forgotten, religious troubles developed (see French Wars of Religion) and epidemics, all of which affected the city. Nîmes, which was one of the Protestant strongholds, felt the full force of repression and fratricidal confrontations (including the Michelade massacre) which continued until the middle of the 17th century, adding to the misery of periodic outbreaks of plague.

17th century to the French Revolution

In the middle of the 17th century Nîmes experienced a period of prosperity. Population growth caused the town to expand, and slum housing to be replaced. To this period also belong the reconstruction of Notre-Dame-Saint-Castor, the Bishop's palace and numerous mansions (hôtels). This renaissance strengthened the manufacturing and industrial potential of the city, the population rising from 21,000 to 50,000 inhabitants.

In this same period the Fountain gardens, the Quais de la Fontaine, were laid out, the areas surrounding the Maison Carrée and the Amphitheatre were cleared of encroachments, whilst the entire population benefited from the atmosphere of prosperity.

From the French Revolution to the present

Following a European economic crisis that hit Nîmes with full force, the Revolutionary period awoke the slumbering demons of political and religious antagonism. The White Terror added to natural calamities and economic recession, produced murder, pillage and arson until 1815. Order was however restored in the course of the century, and Nîmes became the metropolis of Bas-Languedoc, diversifying its industry into new kinds of activity. At the same time the surrounding countryside adapted to market needs and shared in the general increase of wealth.

During the Second World War, the Maquis resistance fighters Jean Robert and Vinicio Faïta were executed at Nîmes on 22 April 1943. The Nîmes marshalling yards were bombed by American bombers in 1944.

The 2e Régiment Étranger d'Infanterie (2ºREI), the main motorised infantry regiment of the Foreign Legion, has been garrisoned in Nîmes since November 1983.[20]

Geography

Climate

Nîmes is one of the warmest cities in France. The city has a humid subtropical climate (Köppen: Cfa), with summers being too wet for it to be classified as a hot-summer Mediterranean climate (Köppen: Csa). Its slightly inland, southerly location results in hot air over the city during summer months: temperatures above 34 °C are common in July and August, whereas winters are cool but not cold. Nighttime low temperatures below 0 °C are common from December to February, while snowfall occurs every year.

| Climate data for Nîmes (Météo France Office-Courbessac, altitude 59m, 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1922–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 21.5 (70.7) |

25.1 (77.2) |

27.3 (81.1) |

30.7 (87.3) |

34.7 (94.5) |

44.4 (111.9) |

40.3 (104.5) |

41.6 (106.9) |

36.8 (98.2) |

31.9 (89.4) |

26.1 (79.0) |

20.9 (69.6) |

44.4 (111.9) |

| Mean maximum °C (°F) | 17.9 (64.2) |

19.2 (66.6) |

23.4 (74.1) |

26.3 (79.3) |

30.2 (86.4) |

34.8 (94.6) |

36.4 (97.5) |

36.8 (98.2) |

32.0 (89.6) |

26.7 (80.1) |

21.2 (70.2) |

17.7 (63.9) |

37.8 (100.0) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 11.4 (52.5) |

12.9 (55.2) |

16.7 (62.1) |

19.5 (67.1) |

23.6 (74.5) |

28.3 (82.9) |

31.5 (88.7) |

31.2 (88.2) |

26.1 (79.0) |

20.9 (69.6) |

15.2 (59.4) |

11.8 (53.2) |

20.8 (69.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 7.3 (45.1) |

8.1 (46.6) |

11.5 (52.7) |

14.1 (57.4) |

18.0 (64.4) |

22.3 (72.1) |

25.2 (77.4) |

24.9 (76.8) |

20.5 (68.9) |

16.3 (61.3) |

11.0 (51.8) |

7.8 (46.0) |

15.6 (60.1) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 3.2 (37.8) |

3.3 (37.9) |

6.2 (43.2) |

8.7 (47.7) |

12.4 (54.3) |

16.3 (61.3) |

18.9 (66.0) |

18.6 (65.5) |

14.9 (58.8) |

11.6 (52.9) |

6.9 (44.4) |

3.8 (38.8) |

10.4 (50.7) |

| Mean minimum °C (°F) | −2.7 (27.1) |

−2.2 (28.0) |

−0.1 (31.8) |

3.1 (37.6) |

7.2 (45.0) |

11.4 (52.5) |

14.4 (57.9) |

14.1 (57.4) |

9.5 (49.1) |

5.0 (41.0) |

−0.1 (31.8) |

−2.5 (27.5) |

−4.1 (24.6) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −12.2 (10.0) |

−14.0 (6.8) |

−6.8 (19.8) |

−2.0 (28.4) |

1.1 (34.0) |

5.4 (41.7) |

10.0 (50.0) |

9.2 (48.6) |

5.4 (41.7) |

−1.0 (30.2) |

−4.8 (23.4) |

−9.7 (14.5) |

−14.0 (6.8) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 64.1 (2.52) |

40.1 (1.58) |

44.7 (1.76) |

67.1 (2.64) |

55.1 (2.17) |

43.0 (1.69) |

30.2 (1.19) |

44.4 (1.75) |

100.3 (3.95) |

95.0 (3.74) |

97.1 (3.82) |

53.3 (2.10) |

734.4 (28.91) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 5.8 | 4.9 | 5.0 | 6.8 | 6.0 | 4.4 | 3.0 | 3.6 | 5.2 | 6.4 | 7.9 | 5.7 | 64.8 |

| Average snowy days | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 2.4 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 71 | 68 | 63 | 63 | 64 | 61 | 56 | 60 | 67 | 73 | 72 | 72 | 65.8 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 141.6 | 165.4 | 219.6 | 229.2 | 268.5 | 312.7 | 346.0 | 307.4 | 244.7 | 171.1 | 141.5 | 132.2 | 2,679.8 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 51 | 51 | 56 | 57 | 59 | 68 | 77 | 74 | 64 | 55 | 50 | 49 | 59 |

| Source 1: Météo France[21] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: NOAA (percent sunshine 1961-1990),[22] Infoclimat.fr (humidity 1961-1990)[23] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Nîmes (Garons, altitude 59m, 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1964–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 20.5 (68.9) |

23.8 (74.8) |

26.9 (80.4) |

29.6 (85.3) |

35.1 (95.2) |

44.1 (111.4) |

40.1 (104.2) |

39.9 (103.8) |

35.3 (95.5) |

31.3 (88.3) |

26.3 (79.3) |

20.3 (68.5) |

44.1 (111.4) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 10.9 (51.6) |

12.3 (54.1) |

16.2 (61.2) |

18.9 (66.0) |

23.0 (73.4) |

27.7 (81.9) |

30.7 (87.3) |

30.3 (86.5) |

25.5 (77.9) |

20.3 (68.5) |

14.7 (58.5) |

11.3 (52.3) |

20.1 (68.2) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 7.1 (44.8) |

7.9 (46.2) |

11.3 (52.3) |

13.8 (56.8) |

17.7 (63.9) |

22.0 (71.6) |

24.7 (76.5) |

24.5 (76.1) |

20.2 (68.4) |

16.0 (60.8) |

10.9 (51.6) |

7.7 (45.9) |

15.3 (59.5) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 3.4 (38.1) |

3.5 (38.3) |

6.3 (43.3) |

8.8 (47.8) |

12.5 (54.5) |

16.3 (61.3) |

18.8 (65.8) |

18.6 (65.5) |

15.0 (59.0) |

11.7 (53.1) |

7.1 (44.8) |

4.0 (39.2) |

10.5 (50.9) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −10.9 (12.4) |

−8.4 (16.9) |

−7.0 (19.4) |

−0.7 (30.7) |

3.3 (37.9) |

6.6 (43.9) |

10.8 (51.4) |

10.3 (50.5) |

6.1 (43.0) |

1.9 (35.4) |

−3.8 (25.2) |

−7.3 (18.9) |

−10.9 (12.4) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 58.3 (2.30) |

36.8 (1.45) |

44.7 (1.76) |

64.5 (2.54) |

48.3 (1.90) |

35.4 (1.39) |

23.7 (0.93) |

34.8 (1.37) |

101.9 (4.01) |

92.0 (3.62) |

93.4 (3.68) |

50.8 (2.00) |

684.6 (26.95) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 5.7 | 4.9 | 4.6 | 6.2 | 5.8 | 3.9 | 2.8 | 3.5 | 5.1 | 6.3 | 7.2 | 5.5 | 61.3 |

| Source: Météo-France[24] | |||||||||||||

| Town | Sunshine (hours/yr) |

Rain (mm/yr) | Snow (days/yr) | Storm (days/yr) | Fog (days/yr) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| National average | 1,973 | 770 | 14 | 22 | 40 |

| Nîmes | 2,664 | 761.3 | 2.4 | 23.6 | 10.6[26] |

| Paris | 1,661 | 637 | 12 | 18 | 10 |

| Nice | 2,724 | 767 | 1 | 29 | 1 |

| Strasbourg | 1,693 | 665 | 29 | 29 | 56 |

| Brest | 1,605 | 1,211 | 7 | 12 | 75 |

Sights

Several important remains of the Roman Empire can still be seen in and around Nîmes:

- The elliptical Roman amphitheatre, of the 1st or 2nd century AD, is the best-preserved Roman arena in France. It was filled with medieval housing, when its walls served as ramparts, but they were cleared under Napoleon. It is still used as a bull fighting and concert arena.

- The Maison Carrée (Square House), a small Roman temple dedicated to sons of Agrippa was built c. 19 BCE. It is one of the best-preserved Roman temples anywhere. Visitors can watch a short film about the history of Nîmes inside.

- The 18th-century Jardins de la Fontaine (Gardens of the Fountain) built around the Roman thermae ruins.

- The nearby Pont du Gard, also built by Agrippa, is a well-preserved aqueduct that used to carry water across the small Gardon river valley.

- The nearby Mont Cavalier is crowned by the Tour Magne ("Great Tower"), a ruined Roman tower.[27]

- The castellum divisorium, a rare vestige of a Roman water inlet system.

Later monuments include:

- The cathedral (dedicated to Saint Castor of Apt, a native of the city), occupying, it is believed, the site of the temple of Augustus, is partly Romanesque and partly Gothic in style.

- The Musée des Beaux-Arts de Nîmes

- The Musée de la Romanité, a museum dedicated to Roman history, located outside the amphitheatre

Pieces of modern architecture can also be found : Norman Foster conceived the Carré d'art (1986), a museum of modern art and mediatheque, and Jean Nouvel designed the Nemausus, a post-modern residential ensemble.

Economy

Nîmes is historically known for its textiles. Denim, the fabric of blue jeans, derives its name from this city (Serge de Nîmes). The blue dye was imported via Genoa from Lahore the capital of the Great Mughal.

Population

The population of Roman Nîmes (50 AD) was estimated at 50–60,000. The population of Nîmes increased from 128,471 in 1990 to 146,709 in 2012, yet the biggest growth the city ever experienced happened in 1968, with a growth of +23.5% compared to 1962.

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Source: EHESS[28] and INSEE (1968-2017)[29] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Culture

From 1810 to 1822, Joseph Gergonne published in Nîmes a scientific journal specializing in mathematics called Annales de Gergonne.

The asteroid 51 Nemausa was named after Nîmes, where it was discovered in 1858.

Twice each year, Nîmes hosts one of the main French bullfighting events, Feria de Nîmes (festival), and several hundreds of thousands gather in the streets.

In 2005 Rammstein filmed their #1 live Album Völkerball in Nîmes.

Metallica's live DVD Français Pour une Nuit (English: French for One Night) was recorded in Nîmes, France, in the Arena of Nîmes on 7 July 2009, during the World Magnetic Tour.

Transportation

Nîmes-Alès-Camargue-Cévennes Airport serves the city, although its proximity with the much bigger Montpellier Airport has worked against its frequentation over the years. It is currently only served by Ryanair with an average of 3 flights per day, to destinations such as London, Fez, Dublin or Marrakech.[30]

The motorway A9 connects Nîmes with Orange, Montpellier, Narbonne, and Perpignan, the A54 with Arles and Salon-de-Provence.

Nîmes station is the central railway station, offering connections to Paris (high-speed rail), Marseille, Montpellier, Narbonne, Toulouse, Perpignan, Figueres and Barcelona in Spain and several regional destinations. There is another station in the Saint-Césaire quarter, Saint-Césaire station, with connections to Le Grau-du-Roi, Montpellier and Avignon.

The new contournement Nîmes – Montpellier high-speed rail line opened to passenger service on 15 December 2019 together with a new TGV station at Nîmes-Pont-du-Gard station, located 12 km outside the city. The station is also located on the existing route between Nìmes and Avignon, thus providing connections between the new line and local rail service.

Nîmes bus station is adjacent to the city centre railway station. Buses connect the city with nearby towns and villages not served by rail.[31]

Sport

The association football club Nîmes Olympique, currently playing in Championnat National, is based in Nîmes.

World Archery Indoor World Cup takes place in Nîmes each year in mid January.

The local rugby union team is RC Nîmes.

The Olympic swimming champion Yannick Agnel was born in Nîmes.

The city hosted the opening stages of the 2017 Vuelta a España cycling race, and is often featured as a stage of the Tour de France.

Mayors

- Émile Jourdan, PCF (1965–1983)

- Jean Bousquet, UDF (1983–1995)

- Alain Clary, PCF (1995–2001)

- Jean-Paul Fournier, LR (since 2001)

Notable people

- Emmanuel Boileau de Castelnau (1857–1923), French alpinist

- Jean-César Vincens-Plauchut (1755–1801), French politician

Twin towns – sister cities

Nîmes is twinned with:[32][33]

Preston, United Kingdom, since 1955

Preston, United Kingdom, since 1955 Verona, Italy, since 1960

Verona, Italy, since 1960 Braunschweig, Germany, since 1962

Braunschweig, Germany, since 1962 Prague 1, Czech Republic, since 1967

Prague 1, Czech Republic, since 1967 Frankfurt (Oder), Germany, since 1976

Frankfurt (Oder), Germany, since 1976 Córdoba, Spain

Córdoba, Spain Rishon LeZion, Israel, since 1986

Rishon LeZion, Israel, since 1986 Meknes, Morocco, since 2005

Meknes, Morocco, since 2005 Fort Worth, United States, since 2019

Fort Worth, United States, since 2019

See also

References

- ↑ "Répertoire national des élus: les maires" (in French). data.gouv.fr, Plateforme ouverte des données publiques françaises. 6 June 2023.

- ↑ "Populations légales 2021". The National Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies. 28 December 2023.

- ↑ Populations légales 2019: 30 Gard Archived 27 October 2022 at the Wayback Machine, INSEE

- ↑ "Nîmes, the most Roman city outside Italy, just got more Roman". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 30 July 2018.

- ↑ Frank Sear (1983). Roman Architecture. Cornell University Press. p. 213. ISBN 0-8014-9245-9.

- ↑ Trudy Ring; Noelle Watson; Paul Schellinger (28 October 2013). Northern Europe: International Dictionary of Historic Places. Taylor & Francis. p. 853. ISBN 978-1-136-63951-7. Archived from the original on 16 September 2023. Retrieved 7 November 2015.

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 March 2014. Retrieved 19 March 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ MobileReference (1 January 2007). Travel Barcelona, Spain for Smartphones and Mobile Devices – City Guide, Phrasebook, and Maps. MobileReference. p. 428. ISBN 978-1-60501-059-5.

- ↑ Woodard, Roger D. (2008). The Ancient Languages of Europe. Cambridge University Press. p. 183. ISBN 978-1-139-46932-6. Archived from the original on 16 September 2023. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- ↑ Dupraz, Emmanuel. "Commémorations cultuelles gallo-grecques chez les Volques Arécomiques". In: Etudes Celtiques, vol. 44, 2018. pp. 36-38. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3406/ecelt.2018.2180 Archived 16 September 2023 at the Wayback Machine; www.persee.fr/doc/ecelt_0373-1928_2018_num_44_1_2180

- 1 2 Gates, Charles (2011). Ancient cities: the archaeology of urban life in the ancient Near East and Egypt, Greece and Rome (2nd ed.). London: Routledge. p. 408. ISBN 978-0-203-83057-4.

- ↑ Armit, Ian (19 March 2012). Headhunting and the Body in Iron Age Europe. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-87756-5. Archived from the original on 16 September 2023. Retrieved 28 July 2022.

- ↑ Maddison, Angus (2007), Contours of the World Economy 1–2030 AD: Essays in Macro-Economic History, Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 41, ISBN 9780191647581

- ↑ Colin M. Kraay, "The Chronology of the coinage of Colonia Nemausus", Numismatic Chronicle 15 (1955), pp. 75–87.

- ↑ Alain Veyrac, "Le symbolisme de l'as de Nîmes au crocodile" Archéologie et histoire romaine vol. 1 (1998) (on-line text Archived 5 April 2010 at the Wayback Machine).

- ↑ Netburn, Deborah (24 February 2016). "Earliest Known Medieval Muslim Graves are Discovered in France". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 25 February 2018. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- ↑ Newitz, Annalee (24 February 2016). "Medieval Muslim Graves in France Reveal a Previously Unseen History". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 1 December 2020. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- ↑ "France's Earliest 'Muslim Burials' Found". BBC News. 25 February 2016. Archived from the original on 7 July 2017. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- ↑ Gleize, Yves; Mendisco, Fanny; Pemonge, Marie-Hélène; Hubert, Christophe; Groppi, Alexis; Houix, Bertrand; Deguilloux, Marie-France; Breuil, Jean-Yves (24 February 2016). "Early Medieval Muslim Graves in France: First Archaeological, Anthropological and Palaeogenomic Evidence". PLOS ONE. 11 (2): e0148583. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1148583G. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0148583. PMC 4765927. PMID 26910855.

- ↑ "Official Website of the 2nd Foreign Infantry Regiment, Historique du 2 REI, La Creation (Creation)". Archived from the original on 30 June 2015. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- ↑ "Ficheclim - Nîmes-Courbessac 1991-2020 et records" (PDF) (in French). Meteo France. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 March 2018. Retrieved 5 January 2022.

- ↑ "Nîmes (07645) – WMO Weather Station". NOAA. Archived from the original on 22 July 2019. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- ↑ "Normes et records 1961–1990: Nimes-Courbessac (30) – altitude 59m" (in French). Infoclimat. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- ↑ "Fiche Climatologique Statistiques 1991-2020 et records" (PDF). Météo-France. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 August 2022. Retrieved 25 August 2022.

- ↑ Paris, Nice, Strasbourg, Brest

- ↑ "Normales climatiques 1981-2010 : Nîmes". www.lameteo.org. Archived from the original on 25 August 2022. Retrieved 25 August 2022.

- ↑ Giving rise to the example of rime richissime Gall, amant de la Reine, alla (tour magnanime)/ Gallament de l'Arène a la Tour Magne, à Nîmes, or "Gall, lover of the Queen, passed (magnanimous gesture), gallantly from the Arena to the Tour Magne at Nîmes".

- ↑ Des villages de Cassini aux communes d'aujourd'hui: Commune data sheet Nîmes, EHESS (in French).

- ↑ Population en historique depuis 1968 Archived 19 July 2022 at the Wayback Machine, INSEE

- ↑ Innovante, Otidea : Agence de Communication. "Vols & Destinations - Aéroport de Nîmes Alès Camargue Cévennes | Edeis". www.nimes.aeroport.fr (in French). Archived from the original on 17 December 2019. Retrieved 25 February 2022.

- ↑ "Accueil - Calculateur d'itinéraire du réseau liO en Occitanie". Archived from the original on 25 February 2022. Retrieved 25 February 2022.

- ↑ "Jumelages". nimes.fr (in French). Nîmes. Archived from the original on 7 April 2019. Retrieved 15 November 2019.

- ↑ "Official Nîmes Signing". fwsistercities.org. Fort Worth. Archived from the original on 15 November 2019. Retrieved 15 November 2019.

Further reading

External links

- City council website

- The official Web site of Roman Nîmes Archived 17 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine