| Part of a series on |

| Software development |

|---|

Object-oriented analysis and design (OOAD) is a technical approach for analyzing and designing an application, system, or business by applying object-oriented programming, as well as using visual modeling throughout the software development process to guide stakeholder communication and product quality.

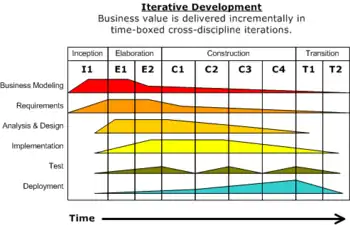

OOAD in modern software engineering is typically conducted in an iterative and incremental way. The outputs of OOAD activities are analysis models (for OOA) and design models (for OOD) respectively. The intention is for these to be continuously refined and evolved, driven by key factors like risks and business value.

History

In the early days of object-oriented technology before the mid-1990s, there were many different competing methodologies for software development and object-oriented modeling, often tied to specific Computer Aided Software Engineering (CASE) tool vendors. No standard notations, consistent terms and process guides were the major concerns at the time, which degraded communication efficiency and lengthened learning curves.

Some of the well-known early object-oriented methodologies were from and inspired by gurus such as Grady Booch, James Rumbaugh, Ivar Jacobson (the Three Amigos), Robert Martin, Peter Coad, Sally Shlaer, Stephen Mellor, and Rebecca Wirfs-Brock.

In 1994, the Three Amigos of Rational Software started working together to develop the Unified Modeling Language (UML). Later, together with Philippe Kruchten and Walker Royce (eldest son of Winston Royce), they have led a successful mission to merge their own methodologies, OMT, OOSE and Booch method, with various insights and experiences from other industry leaders into the Rational Unified Process (RUP), a comprehensive iterative and incremental process guide and framework for learning industry best practices of software development and project management.[1] Since then, the Unified Process family has become probably the most popular methodology and reference model for object-oriented analysis and design.

Overview

The software life cycle is typically divided up into stages going from abstract descriptions of the problem to designs then to code and testing and finally to deployment. The earliest stages of this process are analysis and design. The analysis phase is also often called "requirements acquisition".

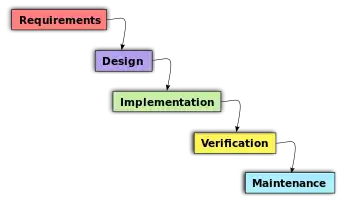

In some approaches to software development—known collectively as waterfall models—the boundaries between each stage are meant to be fairly rigid and sequential. The term "waterfall" was coined for such methodologies to signify that progress went sequentially in one direction only, i.e., once analysis was complete then and only then was design begun and it was rare (and considered a source of error) when a design issue required a change in the analysis model or when a coding issue required a change in design.

The alternative to waterfall models are iterative models. This distinction was popularized by Barry Boehm in a very influential paper on his Spiral Model for iterative software development. With iterative models it is possible to do work in various stages of the model in parallel. So for example it is possible—and not seen as a source of error—to work on analysis, design, and even code all on the same day and to have issues from one stage impact issues from another. The emphasis on iterative models is that software development is a knowledge-intensive process and that things like analysis can't really be completely understood without understanding design issues, that coding issues can affect design, that testing can yield information about how the code or even the design should be modified, etc.[2]

Although it is possible to do object-oriented development using a waterfall model, in practice most object-oriented systems are developed with an iterative approach. As a result, in object-oriented processes "analysis and design" are often considered at the same time.

The object-oriented paradigm emphasizes modularity and re-usability. The goal of an object-oriented approach is to satisfy the "open–closed principle". A module is open if it supports extension, or if the module provides standardized ways to add new behaviors or describe new states. In the object-oriented paradigm this is often accomplished by creating a new subclass of an existing class. A module is closed if it has a well defined stable interface that all other modules must use and that limits the interaction and potential errors that can be introduced into one module by changes in another. In the object-oriented paradigm this is accomplished by defining methods that invoke services on objects. Methods can be either public or private, i.e., certain behaviors that are unique to the object are not exposed to other objects. This reduces a source of many common errors in computer programming.[3]

The software life cycle is typically divided up into stages going from abstract descriptions of the problem to designs then to code and testing and finally to deployment. The earliest stages of this process are analysis and design. The distinction between analysis and design is often described as "what vs. how". In analysis developers work with users and domain experts to define what the system is supposed to do. Implementation details are supposed to be mostly or totally (depending on the particular method) ignored at this phase. The goal of the analysis phase is to create a functional model of the system regardless of constraints such as appropriate technology. In object-oriented analysis this is typically done via use cases and abstract definitions of the most important objects. The subsequent design phase refines the analysis model and makes the needed technology and other implementation choices. In object-oriented design the emphasis is on describing the various objects, their data, behavior, and interactions. The design model should have all the details required so that programmers can implement the design in code.[4]

Object-oriented analysis

The purpose of any analysis activity in the software life-cycle is to create a model of the system's functional requirements that is independent of implementation constraints.

The main difference between object-oriented analysis and other forms of analysis is that by the object-oriented approach we organize requirements around objects, which integrate both behaviors (processes) and states (data) modeled after real world objects that the system interacts with. In other or traditional analysis methodologies, the two aspects: processes and data are considered separately. For example, data may be modeled by ER diagrams, and behaviors by flow charts or structure charts.

Common models used in OOA are use cases and object models. Use cases describe scenarios for standard domain functions that the system must accomplish. Object models describe the names, class relations (e.g. Circle is a subclass of Shape), operations, and properties of the main objects. User-interface mockups or prototypes can also be created to help understanding.[5]

Object-oriented design

During object-oriented design (OOD), a developer applies implementation constraints to the conceptual model produced in object-oriented analysis. Such constraints could include the hardware and software platforms, the performance requirements, persistent storage and transaction, usability of the system, and limitations imposed by budgets and time. Concepts in the analysis model which is technology independent, are mapped onto implementing classes and interfaces resulting in a model of the solution domain, i.e., a detailed description of how the system is to be built on concrete technologies.[6]

Important topics during OOD also include the design of software architectures by applying architectural patterns and design patterns with the object-oriented design principles.

Object-oriented modeling

Object-oriented modeling (OOM) is a common approach to modeling applications, systems, and business domains by using the object-oriented paradigm throughout the entire development life cycles. OOM is a main technique heavily used by both OOD and OOA activities in modern software engineering.

Object-oriented modeling typically divides into two aspects of work: the modeling of dynamic behaviors like business processes and use cases, and the modeling of static structures like classes and components. OOA and OOD are the two distinct abstract levels (i.e. the analysis level and the design level) during OOM. The Unified Modeling Language (UML) and SysML are the two popular international standard languages used for object-oriented modeling.[7]

The benefits of OOM are:

Efficient and effective communication

Users typically have difficulties in understanding comprehensive documents and programming language codes well. Visual model diagrams can be more understandable and can allow users and stakeholders to give developers feedback on the appropriate requirements and structure of the system. A key goal of the object-oriented approach is to decrease the "semantic gap" between the system and the real world, and to have the system be constructed using terminology that is almost the same as the stakeholders use in everyday business. Object-oriented modeling is an essential tool to facilitate this.

Useful and stable abstraction

Modeling helps coding. A goal of most modern software methodologies is to first address "what" questions and then address "how" questions, i.e. first determine the functionality the system is to provide without consideration of implementation constraints, and then consider how to make specific solutions to these abstract requirements, and refine them into detailed designs and codes by constraints such as technology and budget. Object-oriented modeling enables this by producing abstract and accessible descriptions of both system requirements and designs, i.e. models that define their essential structures and behaviors like processes and objects, which are important and valuable development assets with higher abstraction levels above concrete and complex source code.

See also

- ATLAS Transformation Language (ATL)

- Class-Responsibility-Collaboration card (CRC cards)

- Domain Specific Language (DSL)

- Domain-driven design

- Domain-specific modelling (DSM)

- Meta-Object Facility (MOF)

- Metamodeling

- Model-driven engineering (MDE)

- Model-based testing (MBT)

- Object modeling language

- Object-oriented modeling

- Object-oriented programming

- Object-oriented user interface

- QVT

- Shlaer-Mellor

- Software analysis pattern

- Story-driven modeling

- Unified Modeling Language (UML)

- XML Metadata Interchange (XMI)

References

- ↑ "Rational Unified Process Best Practices for Software Development Teams" (PDF). Rational Software White Paper (TP026B). 1998. Retrieved 12 December 2013.

- ↑ Boehm B, "A Spiral Model of Software Development and Enhancement", IEEE Computer, IEEE, 21(5):61-72, May 1988

- ↑ Meyer, Bertrand (1988). Object-Oriented Software Construction. Cambridge: Prentise Hall International Series in Computer Science. p. 23. ISBN 0-13-629049-3.

- ↑ Jacobsen, Ivar; Magnus Christerson; Patrik Jonsson; Gunnar Overgaard (1992). Object Oriented Software Engineering. Addison-Wesley ACM Press. pp. 15, 199. ISBN 0-201-54435-0.

- ↑ Jacobsen, Ivar; Magnus Christerson; Patrik Jonsson; Gunnar Overgaard (1992). Object Oriented Software Engineering. Addison-Wesley ACM Press. pp. 77–79. ISBN 0-201-54435-0.

- ↑ Conallen, Jim (2000). Building Web Applications with UML. Addison Wesley. p. 147. ISBN 0201615770.

- ↑ Jacobsen, Ivar; Magnus Christerson; Patrik Jonsson; Gunnar Overgaard (1992). Object Oriented Software Engineering. Addison-Wesley ACM Press. pp. 15, 199. ISBN 0-201-54435-0.

Further reading

- Grady Booch. "Object-oriented Analysis and Design with Applications, 3rd edition":http://www.informit.com/store/product.aspx?isbn=020189551X Addison-Wesley 2007.

- Rebecca Wirfs-Brock, Brian Wilkerson, Lauren Wiener. Designing Object Oriented Software. Prentice Hall, 1990. [A down-to-earth introduction to the object-oriented programming and design.]

- A Theory of Object-Oriented Design: The building-blocks of OOD and notations for representing them (with focus on design patterns.)

- Martin Fowler. Analysis Patterns: Reusable Object Models. Addison-Wesley, 1997. [An introduction to object-oriented analysis with conceptual models]

- Bertrand Meyer. Object-oriented software construction. Prentice Hall, 1997

- Craig Larman. Applying UML and Patterns – Introduction to OOA/D & Iterative Development. Prentice Hall PTR, 3rd ed. 2005.,mnnm,n,nnn

- Setrag Khoshafian. Object Orientation.

- Ulrich Norbisrath, Albert Zündorf, Ruben Jubeh. Story Driven Modeling. Amazon Createspace. p. 333., 2013. ISBN 9781483949253.

External links

- Article Object-Oriented Analysis and Design with UML and RUP an overview (also about CRC cards).

- Applying UML – Object Oriented Analysis & Design tutorial

- OOAD & UML Resource website and Forums – Object Oriented Analysis & Design with UML.

- Software Requirement Analysis using UML article by Dhiraj Shetty.

- Article Object-Oriented Analysis in the Real World