Abrahamic religions believe in the Mosaic covenant (named after Moses), also known as the Sinaitic covenant (after the biblical Mount Sinai), which refers to a covenant between the Israelite tribes and their God, including their proselytes, not limited to the ten commandments, nor the event when they were given, but including the entirety of laws that their legendary patriarch Moses delivered from God in the five books of Torah.[1][2]

Historical-critical scholarship

The concept of a covenant began long before the biblical era, specifically the beginnings of Israel. According to George E. Mendenhall, covenants were originally established as legal customs and then later were replicated in the field of religion. These covenants were created on the basis of an oath, a promise between two parties followed by performance. Engaging in an oath implied that the more powerful party would ensure that the other received proper punishment if it were to default. In the case of religion, the god(s) would be carrying out punishment. Such covenants assured that either blessings or curses be enacted in response to the circumstances.

The covenant of the pieces between God and Abraham follows the form of the suzerain covenant; what is significant is that Israel has no duties to uphold; the covenant is not conditional. Future covenants between Israel and God would be conditional. This is clearly expressed in Deuteronomy 11:13–21, recited twice-daily as part of the foundational prayer, the Shema. This passage declares that as long as Israel is faithful to God it will be blessed with ample crops but should it follow other gods the land will not support it. The cost of not following this covenant is hard.

Mendenhall also addresses the theory behind blood ties and their significance to the concept of a covenant. As stated in the Bible, Abraham, Isaac and Jacob are the ancestors of Israel and because of their shared blood, they consequently form a bond. This blood tie is compared to the tie that is established by a covenant, and implies that without their shared blood, covenants would be the only way to ensure such unification of a religious group. Furthermore, Mendenhall notes two additional theories noting how covenants may have begun with the work of Moses, or are even thought to have been established during a true historical event with a valid setting. Regardless of the theories, the creation of covenants may be a mystery to scholars for centuries to come, however, the use of covenants evidenced throughout the biblical sources is an undeniable fact. [3]

According to Mendenhall, the covenant was not just an idea, but actually a historical event. This event was the formation of the covenant community. Wandering the desert, the clans left Egypt following Moses. These people were all of different backgrounds, containing no status in any social community. With all these circumstances they formed their own community by a covenant whose texts turned into the Decalogue (Ten Commandments). The Israelites did not bind themselves to Moses as their leader though and Moses was not a part of the covenant. Moses was just seen as a historical figure of some type sent as a messenger. The Israelites followed the form of the suzerainty treaty, a particular type of covenant common in the Near East and were bound to obey stipulations that were set by Yahweh, not Moses.[4]

In addition to Mendenhall's input and perspective, Weinfeld[5] argues that there are two forms of covenants to have occurred throughout the Hebrew Bible: 1.) the obligatory type & 2.) the promissory type. These translate to a “political treaty” as evidenced by the Hittite Empire, and a "royal grant" as shown through the covenants tied to Abraham and David. A treaty entails a promise to the master by the vassal and ultimately protects the rights of the master. This consequently works in a manner that promotes future loyalty of the vassal since the suzerain had previously done favors for them. A grant on the other hand pertains to an obligation from the master to his servant thus ensuring protection of the servant's rights.[6]

This method of covenant emphasizes focus on rewarding loyalty and good deeds that have already been done. Weinfeld supports his characterization of a treaty by identifying the parallels exposed through the covenant between Yahweh and Israel. Similarly, he utilizes the Abrahamic and Davidic covenant to reveal its correspondence with a royal grant. In spite of the numerous theories revolving covenants in the ancient Near East, Weinfeld ensures his readers that the covenants exposed in the Old Testament fall beneath one of the two plausible types he has identified, either an obligatory type or a promissory type.

In an article comparing covenants and forms of treaties common at the time, Mendenhall focuses on Hittite suzerainty treaties. These treaties, established between an emperor (suzerain) and inferior king (vassal), were defined by several important elements. The treaties were based on past aid or good fortune that the suzerain had previously delivered to the vassal and the obligations that the vassal, therefore, had to the suzerain. This foundation for a treaty relationship is similar to the foundation for the Mosaic covenant and the Decalogue, according to Mendenhall. God had delivered the Israelites from Egypt in the Exodus, and they therefore are obligated to follow the commandments in the Decalogue. As the suzerain, God has no further obligations towards the Israelites—but it is implied that God will continue to protect them as a result of the covenant.[7]

Judaism

In the Hebrew Bible, God established the Mosaic covenant with the Israelites after he saved them from slavery in Egypt in the story of the Exodus. Moses led the Israelites to the promised land known as Canaan after which Joshua led them to its possession.

The Mosaic covenant played a role in defining the Kingdom of Israel (c. 1220-c. 930 BC), and subsequently the southern Kingdom of Judah (c. 930-c. 587 BC) and northern Kingdom of Israel (c. 930-c. 720 BC), and Yehud Medinata (c.539-c.333 BC), and the Hasmonean Kingdom (140-37 BC), and the Bar Kokhba revolt (132-136 AD), and Rabbinic Judaism c. 2nd century to the present.

Rabbinic Judaism asserts that the Mosaic covenant was presented to the Jewish people and converts to Judaism (which includes the biblical proselytes) and does not apply to Gentiles, with the notable exception of the Seven Laws of Noah which apply to all people.

Christianity

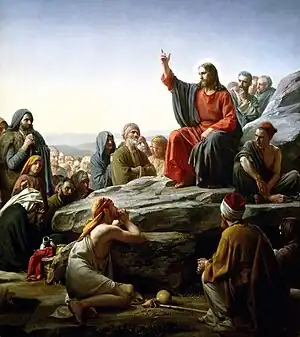

The Mosaic covenant or Law of Moses, which Christians generally call the "Old Covenant" in contrast to the New Covenant, has played an important role in the shaping of Christianity. It has been the source of serious dispute and contention seen in Jesus' expounding of the Law during his Sermon on the Mount, the circumcision controversy in early Christianity, and the Incident at Antioch which has led scholars to dispute the relationship between Paul of Tarsus and Judaism. The Book of Acts says that after the ascension of Jesus, Stephen, the first Christian martyr, was killed when he was accused of speaking against the Jerusalem Temple and the Mosaic Law.[9] Later, in Acts 15:1–21, the Council of Jerusalem addressed the circumcision controversy in early Christianity.

See also

References

- ↑ Jewish Encyclopedia: Proselyte: "...Isa. lvi. 3-6 enlarges on the attitude of those that joined themselves to Yhwh, "to minister to Him and love His name, to be His servant, keeping the Sabbath from profaning it, and laying hold on His covenant.""

- ↑ Exodus 20:8: "thy stranger that is within thy gates"

- ↑ Mendenhall, George E. (1954). "Covenant Forms in Israelite Tradition". The Biblical Archaeologist. The American Schools of Oriental Research. 17 (3): 49–76. doi:10.2307/3209151. JSTOR 3209151. S2CID 166165146.

- ↑ Mendenhall, George E. (1954). "Covenant Forms in Israelite Tradition". The Biblical Archaeologist. The American Schools of Oriental Research. 17 (3): 49–76. doi:10.2307/3209151. JSTOR 3209151. S2CID 166165146.

- ↑ M. Weinfeld

- ↑ Weinfeld, M. (Apr–Jun 1970). "The Covenant of Grant in the Old Testament and in the Ancient near East". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 90 (2): 184–203. doi:10.2307/598135. JSTOR 598135.

- ↑ Mendenhall, George E. (Sept. 1954). "Covenant Forms in Israelite Tradition". The Biblical Archaeologist (New Haven, Conn.: The American Schools of Oriental Research)

- ↑ Such as Hebrews 8:6 etc. See also Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.: "The central thought of the entire Epistle is the doctrine of the Person of Christ and His Divine mediatorial office.... There He now exercises forever His priestly office of mediator as our Advocate with the Father (vii, 24 sq.)."

- ↑ Acts 6:8–14