| Oliver Cowdery | |

|---|---|

Daguerreotype of Oliver Cowdery found in the Library of Congress, taken in the 1840s by James Presley Ball | |

| Assistant Counselor in the First Presidency | |

| September 3, 1837 – April 11, 1838 | |

| End reason | Resignation / Excommunication |

| Assistant President of the Church | |

| December 5, 1834 – April 11, 1838 | |

| End reason | Resignation / Excommunication |

| Second Elder of the Church | |

| April 6, 1830 – December 5, 1834 | |

| End reason | Called as Assistant President of the Church |

| Latter Day Saint Apostle | |

| 1829 (aged 22) – April 12, 1838 | |

| Reason | Restoration of priesthood |

| End reason | Resignation / Excommunication |

| Reorganization at end of term | No apostles immediately ordained[1] |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Oliver H. P. Cowdery October 3, 1806 Wells, Vermont, U.S. |

| Died | March 3, 1850 (aged 43) Richmond, Missouri, U.S. |

| Resting place | Richmond Pioneer Cemetery, Missouri, U.S. 39°17′6.76″N 93°58′34.93″W / 39.2852111°N 93.9763694°W |

| Spouse(s) | Elizabeth Ann Whitmer |

| Children | 6 |

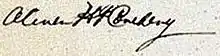

| Signature | |

| |

Oliver H. P. Cowdery[2] (October 3, 1806 – March 3, 1850) was an American religious leader who, with Joseph Smith, was an important participant in the formative period of the Latter Day Saint movement between 1829 and 1836. He was the first baptized Latter Day Saint, one of the Three Witnesses of the Book of Mormon's golden plates, one of the first Latter Day Saint apostles and the Assistant President of the Church.

In 1838, as Assistant President of the Church, Cowdery resigned and was excommunicated on charges of denying the faith. He had claimed that Smith had been engaging in a sexual relationship with Fanny Alger, a teenage servant in his home.[3] Cowdery became a Methodist, but was rebaptized into the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) in 1848.

Biography

Early life

Oliver Cowdery was born October 3, 1806, in Wells, Vermont; his father, William, moved the family to the nearby town of Poultney when Cowdery was three years old.[4] His mother, Rebecca Fuller Cowdery, died on September 3, 1809. In his youth, Cowdery hunted for buried treasure using a divining rod, a common practice at the time.[5]

At age 20, Cowdery left Vermont for upstate New York, where his older brothers had settled. He clerked at a store for just over two years and in 1829 became a school teacher in Manchester.[6] Cowdery lodged with different families in the area, including that of Joseph Smith, Sr., who was said to have provided Cowdery with additional information about the golden plates of which Cowdery said he had heard "from all quarters."[7]

Book of Mormon scribe and witness

| Part of a series on the |

| Book of Mormon |

|---|

|

Cowdery met Joseph Smith, Jr. on April 5, 1829—a year and a day before the official founding of the Church of Christ—and heard from him how he had received golden plates containing ancient reformed Egyptian writings.[8] Cowdery told Smith that he had seen the golden plates in a vision before the two had met.[9]

Before meeting Cowdery, Smith had virtually stopped translating after the first 116 pages had been lost by Martin Harris. Working with Cowdery, however, Smith completed the manuscript of what would become the Book of Mormon in a remarkably short period (April 7–June 1829), during what Richard Bushman later called a "burst of rapid-fire translation."[10] Cowdery also unsuccessfully attempted to translate part of the Book of Mormon by himself.[11]

Cowdery and Smith claimed that on May 15, 1829, they received the Aaronic priesthood from the resurrected John the Baptist, after which they baptized each other in the Susquehanna River.[12] Cowdery said that he and Smith later went into the forest and prayed "until a glorious light encircled us, and as we arose on account of the light, three persons stood before us dressed in white, their faces beaming with glory." One of the three announced that he was the Apostle Peter and said the others were the apostles James and John.[13]

Later that year, Cowdery reported sharing a vision, along with Smith and David Whitmer, in which an angel showed him the golden plates. Harris said he saw a similar vision later that day. Cowdery, Whitmer and Harris signed a statement to that effect and became known as the Three Witnesses. Their testimony has subsequently been published in nearly every edition of the Book of Mormon.

Second Elder of the church

When the Church of Christ was organized on April 6, 1830, Smith became "First Elder" and Cowdery "Second Elder." Although Cowdery was technically second in authority to Smith from the organization of the church through 1838, in practice Sidney Rigdon, Smith's "spokesman" and counselor in the First Presidency, began to supplant Cowdery as early as 1831. Cowdery held the position of Assistant President of the Church from 1834 until his excommunication in 1838.[14][15] He was also a member of the first presiding high council of the church, organized in Kirtland, Ohio, in 1834.

On December 18, 1832, Cowdery married Elizabeth Ann Whitmer, the daughter of Peter Whitmer, Sr. and sister of David, John, Jacob and Peter Whitmer, Jr. They had six children, of whom only one daughter survived to maturity.[16][17]

Cowdery helped Smith publish a series of revelations first called the Book of Commandments and later, as revised and expanded, the Doctrine and Covenants. He was also the editor, or on the editorial board, of several early church publications, including the Evening and Morning Star, the Messenger and Advocate and the Northern Times.

When the church created a bank known as the Kirtland Safety Society (KSS) in 1837, Cowdery obtained the money-printing plates. Sent by Smith to Monroe, Michigan, he became president of the Bank of Monroe, in which the church had a controlling interest.[18] Both banks failed that same year. Cowdery moved to the newly founded Latter Day Saint settlement in Far West, Missouri, and suffered ill health through the winter of 1837–38.

Early written history of the church

In 1834 and 1835, with the help of Smith, Cowdery published a contribution to an anticipated "full history of the rise of the church of Latter Day Saints" as a series of articles in the Messenger and Advocate. His version was not entirely congruent with the later official history of the church.[19] For instance, Cowdery ignored Smith's first vision but described an angel (rather than God the Father or Jesus Christ) who called Smith to his work in September 1823. He placed the religious revival that inspired Smith in 1823 (rather than 1820) and stated that this revival experience had caused Smith to pray in his bedroom (rather than the woods of the official history).[20] Further, after first asserting that the revival had occurred in 1821, when Smith was in his "fifteenth year", Cowdery corrected the date to 1823 and stated that it was in Smith's seventeenth year (though 1823 was actually Smith's eighteenth year).[21]

1838 split with Smith

By early 1838, Smith and Cowdery disagreed on three significant issues. First, Cowdery competed with Smith for leadership of the new church and "disagreed with the Prophet's economic and political program and sought a personal financial independence [from the] Zion society that Joseph Smith envisioned."[22] Then, in March 1838, Smith and Rigdon took over the Far West church, which had been under the presidency of W. W. Phelps and Cowdery's brothers-in-law, and initiated policies that Cowdery, Phelps, and the Whitmers believed violated the separation of church and state. Finally, in January 1838, Cowdery wrote his brother Warren that he and Smith:

"had some conversation in which in every instance I did not fail to affirm that which I had said was strictly true. A dirty, nasty, filthy affair of his and Fanny Alger's was talked over in which I strictly declared that I had never deserted from the truth in the matter, and as I supposed was admitted by himself."[23]: 323–325, 347–349

Alger, a teenage maid living with the Smiths in Kirtland, may have been Smith's first plural wife, a practice Cowdery opposed.[23]: 323–325, 347–349

On April 12, 1838, a church court excommunicated Cowdery after he had failed to appear at a hearing on his membership and sent a letter of resignation instead.[24] David Whitmer was also excommunicated from the church at the same time, and apostle Lyman E. Johnson was disfellowshipped;[25] John Whitmer and Phelps had been excommunicated for similar reasons a month earlier.[26]

Cowdery and the Whitmers became known as "the dissenters" but continued to live in and around Far West, where they owned a great deal of property. On June 17, 1838, Rigdon announced to a large Latter Day Saint congregation that the dissenters were "as salt that had lost its savor" and that it was the duty of the faithful to cast them out "to be trodden beneath the feet of men." The Salt Sermon was seen as a threat of violence and an implicit instruction to the Danites, a secret vigilante group.

The Danite Manifesto, a letter addressed to Cowdery and the other dissenters, was signed by some eighty-four Latter Day Saints (but not Smith[27]). It warned:

you shall have three days after you receive this communication to you, including twenty-four hours in each day, for you to depart with your families peaceably; which you may do undisturbed by any person; but in that time, if you do not depart, we will use the means in our power to cause you to depart.[28]

Cowdery and the dissenters fled the county. Reports about their treatment circulated in nearby non-Mormon communities and increased the tension that led to the 1838 Mormon War, which ultimately resulted in the Latter Day Saints' expulsion from Missouri.[23]: 349–353

1838–48

Between 1838 and 1848, Cowdery studied and practiced law in Tiffin, Ohio, where he became a civic and political leader. He joined the local Methodist church and served as secretary in 1844.[29] Cowdery, also edited the local Democratic newspaper until it was learned that he was one of the Three Witnesses, at which time he was reassigned as assistant editor. He was nominated as his district's Democratic Party candidate for the Ohio State Senate in 1846, but was defeated when his Mormon background was discovered.[30] Some contemporary Mormons believed that Cowdery had denied his testimony of the Book of Mormon,[31][32] while others believed he may have repeated his testimony even while estranged from the church.[30] There is no evidence for either scenario.[33]

After the Smith's death on June 27, 1844, a succession crisis split the Latter Day Saint movement. Cowdery's father and brother were followers of James J. Strang, who pressed his claim as the movement's new "Prophet, Seer, and Revelator" by claiming that he had found and translated ancient records engraved upon metal plates, similar to the golden plates Smith had translated in the 1820s.[34] In 1847, Cowdery and his brother moved to Elkhorn, Wisconsin, about twelve miles away from Strang's headquarters in Voree. In Elkhorn he entered law practice with his brother and became co-editor of the Walworth County Democrat. In 1848 he ran for state assemblyman but was again defeated when his Mormon ties were disclosed.[30]

LDS Church member

In 1848, Cowdery traveled to the frontier settlement of Winter Quarters (in present-day Nebraska) to meet with followers of Brigham Young and the Quorum of the Twelve, asking to be reunited with the church.[35] The Twelve referred the application to the high council in Pottawattamie County, Iowa, which convened a meeting with all high priests in the area to consider the matter. After Cowdery convinced the meeting attendees that he no longer maintained any claim to leadership within the church, his application for rebaptism was unanimously approved.[36] On November 12, 1848, Cowdery was rebaptized by Orson Hyde of the Quorum of the Twelve into—what had become following the succession crisis—the LDS Church in Indian Creek at Kanesville, Iowa.

After his rebaptism, Cowdery desired to relocate to the State of Deseret (present-day Utah) in the coming spring or summer, but due to financial and health problems he decided that he would not be able to make the journey in 1849.[36] Because he was not with the LDS settlement in the State of Deseret, he was not immediately given a position of responsibility in the church. However, in July 1849, Young wrote Cowdery a letter inviting him to travel to Washington, D.C., with Almon W. Babbitt to press the State of Deseret's desire for statehood and to draft a formal application.[36] Cowdery's deteriorating health did not allow him to accept this assignment, and within eight months he had died.

In 1912, the official church magazine Improvement Era published a statement by Jacob F. Gates, son of early Mormon leader Jacob Gates, who had died twenty years prior. According to the recollection by his son, the elder Gates had visited Cowdery in 1849 and inquired about his witness testimony concerning the Book of Mormon. Cowdery reportedly reaffirmed his witness:

"Jacob, I want you to remember what I say to you. I am a dying man, and what would it profit me to tell you a lie? I know," said he, "that this Book of Mormon was translated by the gift and power of God. My eyes saw, my ears heard, and my understanding was touched, and I know that whereof I testified is true. It was no dream, no vain imagination of the mind—it was real".[37][38]

On March 3, 1850, Cowdery died in David Whitmer's home in Richmond, Missouri.[39]

As purported co-author of the Book of Mormon

Critics who doubt the origin theory of the Book of Mormon have speculated that Cowdery may have played a role in the work's composition. LDS scholar Daniel Peterson, however, has noted that the original manuscript of the Book of Mormon seems to corroborate Smith's story in that it was in its majority dictated to Cowdery, with aural errors in it; and the Printer's Manuscript, in which Cowdery participated in producing, contains copyist errors with his calligraphy, rendering him unlikely of being aware of the content beforehand.[40]

Speculation of pre-1829 connection between Cowdery and Smith

Cowdery was a third cousin of Lucy Mack Smith, Joseph Smith's mother.[41] There is also a geographical connection between the Smiths and the Cowderys. During the 1790s, both Joseph Smith, Sr. and Lucy Mack Smith, and two of Cowdery's relatives were living in Tunbridge, Vermont.

- New Israelites

Joseph Smith, Sr. and Cowdery's father, William, may have been members of a Congregationalist sect known as the New Israelites, organized in Rutland County, Vermont. The Cowdery family lived in Rutland County in the early 19th century and later attended a Congregationalist church in Poultney, Vermont. Witnesses from Vermont connected William Cowdery to the sect before these witnesses could have known that his son, Oliver, was a dowser.[42]

Vermont residents interviewed by a local historian said that Joseph Smith, Sr. was also a member of the New Israelites and was one of its "leading rods-men".[43] But although residents said that he lived in Poultney, Vermont, "at the time of the Wood movement here",[44] there are no other records placing Smith closer than about 50 miles away. On the other hand, Smith's involvement with the New Israelites would be consistent with his links to Congregationalism and the report from James C. Brewster than in 1837 Smith, Sr. admitted that he entered the money digging business "more than thirty years" ago.[45]

Cowdery and View of the Hebrews

For several years, Cowdery and his family attended the Congregational Church in Poultney, Vermont, when its minister was the Rev. Ethan Smith, author of View of the Hebrews, an 1823 book suggesting that Native Americans were of Hebrew origin, a not uncommon speculation during the colonial and early national periods.[46][47] In 2000, David Persuitte argued that Cowdery's knowledge of View of the Hebrews significantly contributed to the final version of the Book of Mormon,[48] a connection first suggested as early as 1902.[49] Fawn Brodie wrote that it "may never be proved that Joseph saw View of the Hebrews before writing the Book of Mormon, but the striking parallelisms between the two books hardly leave a case for mere coincidence."[50] Richard Bushman and John W. Welch reject the connection and argue that there is little relationship between the contents of the two books.[51]

Footnotes

- ↑ On January 24, 1841, Hyrum Smith was ordained and replaced Cowdery as Assistant President of the Church.

- ↑ Prior to the winter of 1830–31, Cowdery generally signed his name "Oliver H P Cowdery", the "H P" possibly standing for "Hervy" and "Pliny," two of his father's relatives. For unknown reasons, Cowdery discontinued using his middle initials about 1831. Cowdery may have wished his name to match the form in which it was printed in the 1830 Book of Mormon. . It is also possible that teasing by the Palmyra Reflector (June 1, 1830) about his "pretentious moniker" may have influenced Cowdery to abandon the initials.

- ↑ Marquardt (2005, p. 463); Remini (2002, p. 128); Quinn (1994, p. 93); Bushman (2005), pp. 324, 346–348) Smith said Cowdery was leaving his calling to make money and was urging vexatious lawsuits against Mormons.

- ↑ Preston Nibley, Oliver Cowdery: His Life, Character and Testimony (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1958).

- ↑ EMD, 1: 603–05, 619–20; Quinn, 37.

- ↑ Lucy Cowdery Young to Andrew Jenson, March 7, 1887, Church Archives

- ↑ Dan Vogel, Joseph Smith: The Making of a Prophet (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 2004), 154; Junius F. Wells, "Oliver Cowdery", Improvement Era XIV:5 (March 1911); Lucy Mack Smith, "Preliminary Manuscript," 90 in Early Mormon Documents 1: 374–75.

- ↑ Joseph Smith–History 1:66.

- ↑ Palmer, Grant (2002). An Insider's View of Mormon Origins. Salt Lake City, Utah: Signature Books. p. 179.

According to Lucy Mack Smith, the "Lord appeared unto a young man by the name of Oliver Cowdery and showed unto him the plates in a vision."

- ↑ Bushman, Richard (2005). Joseph Smith: Rough Stone Rolling. New York City: Alfred A. Knopf. p. 70. ISBN 9781400077533.

- ↑ History of the Church 1:36-38; D&C 8, 9.

- ↑ Messenger and Advocate 1:14–16 (October 1834); Bushman, 74–75.

- ↑ Charles M. Nielsen to Heber Grant, February 10, 1898, in Dan Vogel, ed., Early Mormon Documents (Salt Lake City, Utah: Signature Books, 1998), 2: 476; History of the Church 1:39–42.

- ↑ Bushman, p. 124

- ↑ Vogel, Dan (2004). Joseph Smith: The Making of a Prophet. Salt Lake City: Signature Books. p. 548. ASIN B07NTCYDQB.

- ↑ Maria Louise Cowdery, born August 11, 1835.

- ↑ Anderson, Richard; Ludlow, Daniel (1992). Encyclopedia of Mormonism. New York: Macmillan. pp. 335–340. ISBN 9780029040409. Retrieved January 30, 2023.

- ↑ See Mark L. Staker, "Raising Money in Righteousness: Oliver Cowdery as Banker," in Days Never to Be Forgotten: Oliver Cowdery, ed. Alexander L. Baugh (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2009), 143–254.

- ↑ W. W. Phelps to Oliver Cowdery, December 25, 1834, EMD, 3: 28

- ↑ Grant Palmer, An Insider's View of Mormon Origins (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 2002), 239; Richard Abanes, One Nation Under Gods: A History of the Mormon Church (New York: Four Walls Eight Windows, 2002), 26; Vogel, EMD, 2: 428.

- ↑ Cowdery said that the final battle between the Nephites and the Lamanites had occurred in the vicinity of the Hill Cumorah, where Smith claimed he found the golden plates. There is little evidence for mass graves for tens of thousands of soldiers at the site. Most modern Mormon apologists now argue that the events likely took place in Central America. Messenger and Advocate, 1, no. 3 (December 1834),42, 78-79. "You will recollect that I mentioned the time of a religious excitement, in Palmyra and vicinity to have been in the 15th year of our brother J. Smith Jr.'s age — that was an error in the type — it should have been in the 17th. — You will please remember this correction, as it will be necessary for the full understanding of what will follow in time. This would bring the date down to the year 1823."

- ↑ Anderson, Richard Lloyd (1992), "Cowdery, Oliver", in Ludlow, Daniel H. (ed.), Encyclopedia of Mormonism, New York, NY: Macmillan Publishing, pp. 335–340, ISBN 0-02-879602-0, OCLC 24502140

- 1 2 3 Bushman, Richard Lyman (2005). Joseph Smith: Rough Stone Rolling. New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf.

- ↑ Bushman, 347–48. Among other things, Cowdery was accused of "virtually denying the faith by declaring that he would not be governed by any ecclesiastical authority nor Revelations whatever in his temporal affairs."

- ↑ History of the Church 3:16–20.

- ↑ History of the Church 3:7.

- ↑ Missouri Documents (Report). p. 106.

Document containing the correspondence, orders &c. in relation to the disturbances with the Mormons; and the evidence given before the Hon. Austin A. King, Judge of the Fifth Judicial Circuit of the State of Missouri, at the Courthouse in Richmond, in a criminal court of inquiry, begun November 12, 1838, on the trial of Joseph Smith, Jr. and others for high treason and other crimes against the state (Missouri. Office of the Secretary of State; Missouri. General Assembly (1840–1841))

- ↑ "Document Showing The Testimony ... on the Trial of Joseph Smith, Jr". olivercowdery.com. Joseph Smith's History Vault.

(Washington D. C.: Blair & Rives, 1841)

- ↑ Vogel, ed. EMD, 2: 504. Gabriel J. Keen, a leading member of the Tiffin Methodist Church, swore in 1885 that Cowdery had publicly renounced Mormonism before being admitted as a member, but there is no corroborative evidence for Keen's claim. The document is at 2: 504-07.

- 1 2 3 Stanley R. Gunn, Oliver Cowdery, Second Elder and Scribe (Salt Lake City, 1962)

- ↑ In 1841, the Mormon periodical Times and Seasons published the following verse: "Or does it prove there is no time,/Because some watches will not go?/...Or prove that Christ was not the Lord/Because that Peter cursed and swore?/Or Book of Mormon not His word/Because denied, by Oliver?" J. H. Johnsons, Times and Seasons 2: 482 (July 15, 1841).

- ↑ Charles Augustus Shook, The True Origin of the Book of Mormon (Cincinnati: Standard Publishing Co., 1914), 54: "At this time it was freely admitted by the Mormons that he had denied his testimony."

- ↑ Cowdery is supposed to have affirmed his Book of Mormon testimony before a court of law while he was acting as a prosecuting attorney. "However, the claim rests on less than satisfactory grounds. The various accounts are inconsistent and some elements of the story troubling. In the earliest account, for instance, Brigham Young (1855) states that the trial occurred in Michigan, while George Q. Cannon (1881) claims that it was in Ohio. Charles M. Neilson (1909–35) inconsistently names Michigan and Illinois. Seymour B. Young (1921) fails to give the trial's location. Presently there is no evidence for Cowdery practicing law in either Michigan or Illinois." Dan Vogel, ed., Early Mormon Documents, 2: 468. The documents themselves are given at 2: 471–90. Two other associates of Cowdery in Tiffin, Ohio, claimed that Cowdery never discussed Mormonism in public or in private. Charles Augustus Shook, The True Origin of the Book of Mormon (Cincinnati: Standard Publishing Co., 1914), 56–57.

- ↑ Grant Palmer, An Insider's View of Mormon Origins (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 2002), 208–13.

- ↑ "Brethren, for a number of years, I have been separated from you. I now desire to come back. I wish to come humble and be one in your midst. I seek no station. I only wish to be identified with you. I am out of the Church, but I wish to become a member. I wish to come in at the door; I know the door, I have not come here to seek precedence. I come humbly and throw myself upon the decision of the body, knowing as I do, that its decisions are right." (Stanley R. Gunn, "Oliver Cowdery Second Elder of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints: A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Division of Religion, Brigham Young University," (1942), 166, as cited in Improvement Era, 24, p. 620.)

- 1 2 3 Scott H. Fauling, "The Return of Oliver Cowdery" Archived October 21, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Maxwell Institute, byu.edu.

- ↑ "Jacob Gates". Grampa Bill. Archived from the original on August 14, 2018. Retrieved April 6, 2008.

- ↑ Scott H. Faulring, The Return of Oliver Cowdery, Maxwell Institute, archived from the original on October 21, 2011, retrieved April 10, 2012; Gates, Jacob F. (March 1912). "Testimony of Jacob Gates". Improvement Era 15. p. 92.

- ↑ Of Cowdery's death, Whitmer said: "Oliver died the happiest man I ever saw. After shaking hands with the family and kissing his wife and daughter, he said 'Now I lay down for the last time; I am going to my Saviour'; and he died immediately with a smile on his face." (Stanley R. Gunn, Oliver Cowdery Second Elder of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints: A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Division of Religion, Brigham Young University. (Stanley R. Gunn: 1942), 170–71, as cited in Millennial Star, XII, p. 207.)

- ↑ "The Logic Tree of Life, or, Why I Can't Manage to Disbelieve - FairMormon conference 2016". FairMormon. Retrieved May 3, 2019.

- ↑ Cowdery genealogy; Richard L. Bushman, Joseph Smith and the Beginnings of Mormonism, (Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 1984), 222; Bushman, RSR, 578, n.51. There is also a distant geographical connection between the Smiths and the Cowderys. During the 1790s, both Joseph Smith, Sr. and two of Oliver Cowdery's relatives were living in Tunbridge, Vermont.

- ↑ Quinn 1998, pp. 25–26; Brooke 1994, p. 133

- ↑ Quinn 1998, pp. 35–36; Brooke 1994, pp. 133.

- ↑ Quinn 1998, pp. 25–26; Brooke 1994, p. 133.

- ↑ Brooke 1994, pp. 133, 39. Brewster reported that in 1837, Smith, Sr. boasted that "I know more about money-digging than any man in this generation for I have been in the business for more than thirty years!"

- ↑ Grant H. Palmer, An Insider's View of Mormon Origins (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 2002), 58–60.

- ↑ Richard Bushman, Rough Stone Rolling, 94–97.

- ↑ David Persuitte, Joseph Smith and the Origins of the Book of Mormon (McFarland & Company, 2000), 125: "Oliver Cowdery surely had a copy of View of the Hebrews—a book that was published in his home town of Poultney, Vermont by the minister of the church his family was associated with. Considering his joint venture with Joseph Smith in 'translating' The Book of Mormon and the common subject matter, Cowdery could have shared his copy of Ethan Smith's book with Joseph, perhaps even sometime before Joseph began the 'translation' process."

- ↑ I. Woodbridge Riley, The Founder of Mormonism (New York: Dodd, Mead & Company, 1902), 124–26.

- ↑ Fawn Brodie, No Man Knows My History (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1971), 47.

- ↑ John W. Welch, Reexploring the Book of Mormon, 83–87, and A Sure Foundation: Answers to Difficult Gospel Questions (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1988); John W. Welch, "An Unparallel" (Provo, Utah: FARMS, 1985); Spencer J. Palmer and William L. Knecht, "View of the Hebrews: Substitute for Inspiration?" BYU Studies 5/2 (1964): 105–13.

References

- Brooke, John L. The Refiner's Fire: The Making of Mormon Cosmology, 1644–1844. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1994.

- Cowdrey, Wayne L. Davis, Howard A. Vinik, Arthur Who Really Wrote the Book of Mormon? The Spalding Enigma Concordia Publishing House: St. Louis, 2005.

- Gunn, Stanley R. Oliver Cowdery, Second Elder and Scribe. Bookcraft: Salt Lake City, 1962. 250–51.

- Legg, Phillip R., Oliver Cowdery: The Elusive Second Elder of the Restoration, Herald House: Independence, Missouri, 1989.

- Mehling, Mary, Cowdrey-Cowdery-Cowdray Genealogy p. 181, Frank Allaben: 1911.

- Morris, Larry E. (2000). "Oliver Cowdery's Vermont Years and the Origins of Mormonism" (PDF). BYU Studies. 39 (1): 105–129. Retrieved June 23, 2009.

- Quinn, D. Michael, Early Mormonism and the Magic World View, Revised and enlarged (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1998), 36–39.

- Smith, Joseph, B. H. Roberts, ed., History of the Church (Salt Lake City: Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1902), seven volumes.

- Vogel, Dan, ed., Early Mormon Documents [EMD] (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1998), five volumes.

- Welch, John W. and Morris, Larry E., eds., Oliver Cowdery: Scribe, Elder, Witness (Provo, UT: The Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, 2006); ISBN 0-8425-2661-7.

Further reading

- Baugh, Alexander (2009), Days Never to Be Forgotten: Oliver Cowdery, BYU, ISBN 978-0-8425-2742-2

- Welch, John (2006), Oliver Cowdery: Scribe, Elder, Witness, Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, ISBN 0842526617

External links

Media related to Oliver Cowdery at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Oliver Cowdery at Wikimedia Commons Quotations related to Oliver Cowdery at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Oliver Cowdery at Wikiquote Works by or about Oliver Cowdery at Wikisource

Works by or about Oliver Cowdery at Wikisource- Oliver Cowdery, by Dale R. Broadhurst, at olivercowdery.com

- Oliver Cowdery's Genealogy, at olivercowdery.com

- Oliver Cowdery at Find a Grave

- Oliver Cowdry legal documents, MSS SC 355 at L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University

- Oliver Cowdrey stipulation in estate settlement, MSS SC 258 at L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University

- Oliver Cowdery notarized affidavit, MSS SC 1035 at L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University

- Oliver Cowdery docket book, MSS 4029 at L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University