The Greek lyric poet Pindar composed odes to celebrate victories at all four Panhellenic Games. Of his fourteen Olympian Odes, glorifying victors at the Ancient Olympic Games, the First was positioned at the beginning of the collection by Aristophanes of Byzantium since it included praise for the games as well as of Pelops, who first competed at Elis (the polis or city-state in which the festival was later staged).[4] It was the most quoted in antiquity[5] and was hailed as the "best of all the odes" by Lucian.[6] Pindar composed the epinikion in honour of his then patron Hieron I, tyrant of Syracuse, whose horse Pherenikos and its jockey were victorious in the single horse race in 476 BC.[1]

Poetry

The ode begins with a priamel, where the rival distinctions of water and gold are introduced as a foil to the true prize, the celebration of victory in song.[7] Ring-composed,[8] Pindar returns in the final lines to the mutual dependency of victory and poetry, where "song needs deeds to celebrate, and success needs songs to make the areta last".[9] Through his association with victors, the poet hopes to be "famed in sophia among Greeks everywhere" (lines 115-6).[1] Yet a fragment of Eupolis suggests Pindar's hopes were frustrated, his compositions soon "condemned to silence by the boorishness of the masses".[10][11]

Pelops

At the heart of the ode is Pindar's "refashioning" of the myth of Pelops, king of Pisa, son of Tantalus, father of Thyestes and Atreus, and hero after whom the Peloponnese or "Isle of Pelops" is named.[9] Pindar rejects the common version of the myth, wherein Tantalus violates the reciprocity of the feast and serves up his dismembered son Pelops to the gods (lines 48-52); Pelops' shoulder is of gleaming ivory (line 35) since Demeter, in mourning for Kore, unsuspectingly ate that part.[12][13] Instead Pindar has Pelops disappear because he is carried off by Poseidon.[12][14] After his "erotic complaisance", Pelops appeals to Poseidon for help, "if the loving gifts of Cyprian Aphrodite result in any gratitude" (lines 75-76);[15] the god grants him a golden chariot and horses with untiring wings (line 87); with these Pelops defeats Oenomaus in a race and wins the hand of his daughter Hippodameia, avoiding the fate of death previously meted out upon a series of vanquished suitors.[13]

In Homo Necans, Walter Burkert reads in these myths a reflection of the sacrificial rites at Olympia.[12][13] The cultic centres of the sanctuary were the altar of Zeus, the stadium, and the tomb of Pelops, where "now he has a share in splendid blood-sacrifices, resting beside the ford of the Alpheus" (lines 90-93).[13] According to Philostratus, after sacrifice and the laying of the consecrated parts upon the altar, the runners would stand one stadion distant from it; once the priest had given the signal with a torch, they would race, with the winner then setting light to the offerings.[13][17] Pindar, subordinating the foot race to that of the four-horse chariot, "could reflect the actual aetiology of the Olympics in the early 5th century [BC]".[12][18]

Patronage

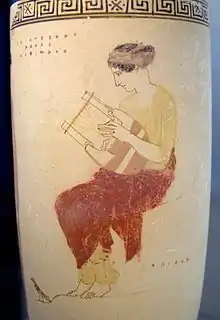

According to Maurice Bowra, the main purpose of the poem is "Pindar's first attempt to deal seriously with the problems of kingship", and especially "the relations of kings with the gods".[5] Hieron, "Pindar's greatest patron" and honorand in four odes and a now-fragmentary encomium,[9] is likened to a Homeric king, as he "sways the sceptre of the law in sheep-rich Sicily" (lines 12-13).[5] Pindar incorporates the ideology of xenia or hospitality into his ode, setting it in the context of a choral performance around Hieron's table, to the strains of the phorminx (lines 15-18).[19] Yet the poet keeps his distance; the central mythological episode is concerned with chariot racing, a more prestigious competition than the single horse race;[12] and Pindar warns Hieron that there are limits to human ambition (line 114).[5]

English translations

- Olympian 1, translated into English verse by Ambrose Philips (1748)

- Olympian 1, translated into English verse by C. A. Wheelwright (1846)

- Olympian 1, translated into English prose by Ernest Myers (1874)

See also

- Ode 5 by Bacchylides (celebrating the same victory)[20]

- Curse of the Atreids

- Greek hero cult

- Nine lyric poets

- Kleos

- Papyrus Oxyrhynchus 222

References

- 1 2 3 "Olympian I". Perseus Project. Retrieved 9 July 2012.

- ↑ Bundrick, Sheramy D. (2005). Music And Image In Classical Athens. Cambridge University Press. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-521-84806-0.

- ↑ Oakley, John H. "The Achilles Painter - White Ground: Middle Phase". Perseus Project. Retrieved 14 July 2012.

- ↑ Drachmann, A. B. (1903). Scholia Vetera in Pindari Carmina (in Ancient Greek). Vol. I. Teubner. p. 7.

- 1 2 3 4 Bowra, Maurice (1964). Pindar. Oxford University Press. pp. 126f.

- ↑ Lucian. "Gallus 7" (in Ancient Greek). Perseus Project. Retrieved 9 July 2012.

- ↑ Verdenius, Willem Jacob (1988). Commentaries on Pindar: Olympian Odes 1, 10, 11, Nemean 11, Isthmian 2. Brill. pp. 4ff. ISBN 90-04-08535-1.

- ↑ Sicking, C. M. J. (1983). "Pindar's First Olympian: an interpretation". Mnemosyne. Brill. 36 (1): 61ff. doi:10.1163/156852583x00043. JSTOR 4431206.

- 1 2 3 Race, William H. (1986). Pindar. Twayne Publishers. pp. 36, 62–4. ISBN 0-8057-6624-3.

- ↑ Athenaeus. "Deipnosophistae I.4" (in Ancient Greek). Perseus Project. Retrieved 12 July 2012.

- ↑ Yunis, Harvey, ed. (2007). Written Texts and the Rise of Literate Culture in Ancient Greece. Cambridge University Press. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-521-03915-4.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Nagy, Gregory (1990). Pindar's Homer: The Lyric Possession of an Epic Past. Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 116f. ISBN 0-8018-3932-7.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Burkert, Walter (1983) [1972]. Homo Necans: the Anthropology of Ancient Greek Sacrificial Ritual and Myth. University of California Press. pp. 93–103. ISBN 0-520-05875-5.

- ↑ Köhnken, Adolf (1974). "Pindar as Innovator: Poseidon Hippios and the Relevance of the Pelops Story in Olympian 1". The Classical Quarterly. Cambridge University Press/The Classical Association. 24 (2): 199–206. doi:10.1017/s0009838800032730. JSTOR 638481. S2CID 170440064.

- ↑ Cairns, Francis (1977). "'ΈΡΩΣ in Pindar's First Olympian Ode". Hermes. Franz Steiner Verlag. 105 (2): 129–132. JSTOR 4476002.

- ↑ Ashmole, Bernard (1967). Olympia: The Sculptures of the Temple of Zeus. Phaidon Press. pp. 6ff., 12ff., 31f.

- ↑ Philostratus. "de Gymnastica 5" (in Ancient Greek). Perseus Project. Retrieved 10 July 2012.

- ↑ Nagy, Gregory (1986). "Pindar's Olympian 1 and the Aetiology of the Olympic Games". Transactions of the American Philological Association. Johns Hopkins University Press. 116: 71–88. doi:10.2307/283911. JSTOR 283911.

- ↑ Kurke, Leslie (1991). The Traffic in Praise: Pindar and the Poetics of Social Economy. Cornell University Press. pp. 136f. ISBN 0-8014-2350-3.

- ↑ Bacchylides. "Ode 5". Perseus Project. Retrieved 12 July 2012.

Further reading

- Gerber, Douglas E. (1982). Pindar's Olympian One: a commentary. University of Toronto Press. pp. 202. ISBN 978-0-802-05507-1.

- Adam, Eugene A. (1962). "Symbolism in the First Olympian Ode". The Classical Outlook. 40 (2): 13–14. JSTOR 43929726.

- Adam, Eugene A. (1962). "Symbolism in the First Olympian Ode". The Classical Outlook. 40 (2): 13–14. JSTOR 43929726.

- Athanassaki, Lucia (2004). "Deixis, Performance, and Poetics in Pindar's "First Olympian Ode"". Arethusa. 37 (3): 317–341. doi:10.1353/are.2004.0015. JSTOR 44578833. S2CID 161706614.

- Cairns, Francis (1977). "'ΈΡΩΣ in Pindar's First Olympian Ode". Hermes. 105 (2): 129–132. JSTOR 4476002.

- Eckerman, Chris (2017). "Pindar's Olympian 1, 1-7 and its Relation to Bacchylides 3, 85-87". Wiener Studien. 130: 7–32. doi:10.1553/wst130s7. JSTOR 44647509.

- Farenga, Vincent (1977). "Violent Structure: The Writing of Pindar's Olympian I". Arethusa. 10 (1): 197–218. JSTOR 26307830.

- Howatson, M. C. (1984). "Pindar's Olympian One". The Classical Review. 34 (2): 173–175. doi:10.1017/S0009840X0010335X. JSTOR 3062375. S2CID 164143431.

- Nagy, Gregory (1986). "Pindar's Olympian 1 and the Aetiology of the Olympic Games". Transactions of the American Philological Association. 116: 71–88. doi:10.2307/283911. JSTOR 283911.

- Nairn, J. Arbuthnot (1901). "On Pindar's Olympian Odes". The Classical Review. 15 (1): 10–15. doi:10.1017/S0009840X00029346. JSTOR 695741. S2CID 162919256.

- Nicholson, Nigel (2007). "Pindar, History, and Historicism". Classical Philology. 102 (2): 208–227. doi:10.1086/523739. JSTOR 10.1086/523739. S2CID 162206930.

- Segal, Charles Paul (1964). "God and Man in Pindar's First and Third Olympian Odes". Harvard Studies in Classical Philology. 68: 211–267. doi:10.2307/310806. JSTOR 310806.

External links

Media related to Pelops at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Pelops at Wikimedia Commons Media related to Oenomaus at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Oenomaus at Wikimedia Commons Works related to Odes of Pindar at Wikisource

Works related to Odes of Pindar at Wikisource- Olympian I (English translation)

- Olympian I (Greek text)