| East Prigorodny conflict | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Post-Soviet conflicts | |||||||

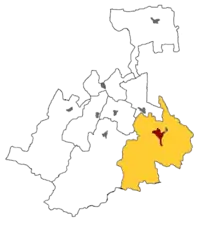

Prigorodny District in North Ossetia–Alania | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

| - | ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

192 dead[2] 379 wounded[2] |

409 dead[3] 457 wounded[4] | ||||||

|

30,000–60,000 Ingush refugees[5] 9,000 Ossetian refugees[3] | |||||||

The East Prigorodny conflict, also referred to as the Ossetian–Ingush conflict,[lower-alpha 1] was an inter-ethnic conflict within Russian Federation, in the eastern part of the Prigorodny District in the Republic of North Ossetia–Alania, which started in 1989 and developed, in 1992, into a brief ethnic war between local Ingush and Ossetian paramilitary forces.[3]

Background

.svg.png.webp)

.jpg.webp)

On October 1928, the leadership of the North Caucasus Krai failed to transfer the city of Vladikavkaz into North Ossetian ASSR because of strong objections from the Ingush Regional Committee of the All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks led by Idris Zyazikov. The transfer would have brought the Ingush irreparable losses as the main industrial enterprises, a hospital, technical schools, educational institutions and many cultural institutions of Ingush Autonomous Oblast were located in Vladikavkaz.[6] On 1 July 1933, after the removal of Zyazikov from the political scene and reprisals against other most stubborn opponents and the Ingush Regional Committee being forced to withdraw its previous objections under pressure, the leadership of the North Caucasusian Krai transferred the city of Vladikavkaz (called from 1931 Ordzhonikidze) into North Ossetian ASSR.[7]

The Prigorodny District was part of the Chechen-Ingush ASSR.[8][9] Prior to the deportation of the Chechens and Ingush, the population was mostly made up of Ingush (28132 out of 33753).[10] In 1944, with the deportation of the Chechens and Ingush and the abolishment of their ASSR, the district was transferred to North Ossetian ASSR.[8][9] Soon, on 8 May 1944, the North Ossetian Regional Committee, headed by Kubadi Kulov, replaced the toponymy in the former Chechen and Ingush raions of Chechen-Ingush ASSR. At the same time, the destruction of Chechen and Ingush cemeteries began, the tombstones from which were used for building material, and 25-35 thousand Ossetians from Georgian SSR were resettled to the Prigorodny District.[11]

In 1957,[12] when the Ingush were returning from the deportation and their ASSR was restored, they were denied the return to Prigorodny District which remained part of the North Ossetian ASSR.[12][9] Those who tried to return to their villages faced considerable hostility. Nevertheless, during the Soviet period some Ingush managed to unofficially purchase and occupy their own houses back but they were never recognized as official residents.[9]

During the Soviet period, programs in support of Ingush language and culture in North Ossetian ASSR were totally lacking. The policies of the ASSR limited Ingush residency in the district and hindered their access to plots of land. The internal police and local courts where Ossetians dominated treated the Ingush with prejudice, especially during the state of emergency imposed in Prigorodny in April 1992.[13]

The constant discrimination of the Ingush forced them to organize the Rally in Grozny on 16–19 January 1973[14] where they demanded that the Soviet authorities solve the problem of the Prigorodny District, provide the Ingush with social equality with the Ossetians. Despite the rally being peaceful, held under the slogans of "friendship of peoples", "restoration of Leninist norms" with the order being maintained by the Ingush themselves, they received no response from the authorities and the rally ended in clashes with the police and the condemnation of its most active participants.[15] According to Idris Bazorkin, after the protest, conditions of Ingush in the Prigorodny District improved somewhat. Ingush language appeared in schools, literature in the Ingush language arrived in the region, broadcasts in the Ingush language began on radio and television, for the first time Ingush deputies appeared in the Ordzhonikidze City Executive Committee and the Prigorodny District Executive Committee. However, much remained the same: authorities continued to limit the registration of Ingush in the district, Ingush children couldn't receive a normal education, discrimination in employment continued and Ingush were negatively portrayed in historical and fiction literature.[16]

The tensions increased in early 1991, during the collapse of the Soviet Union, when the Ingush openly declared their rights to the Prigorodny District according to the Soviet law adopted by the Supreme Soviet of the USSR on 26 April 1991; in particular, the third and the sixth article on "territorial rehabilitation". The law gave the Ingush legal grounds for their demands, which caused serious turbulence in the region.[17] As the tensions grew throughout 1991, Ossetian thugs harassed the Ingush and a slow exodus of refugees began into Ingushetia.[18]

On 20 October 1992, an Ingush girl was crushed by an Ossetian armored personnel carrier and two days later Ossetian traffic police officers shot and killed two Ingush. After the series of murders of Ingush citizens in the district, Ingush deputies requested on 23–24 October the Supreme Soviet of Russia and its government to send a special commission to the Ossetian-Ingush border zone in order to prevent the impending conflict, but no action was taken. On 24 October the leaders of the Prigorodny District gathered in the village of Yuzhny where they called on all local village councils to declare secession from North Ossetia and entry into Ingushetia in accordance with the law of Russia. In addition, an attempt was made to create Ingush self-defense units. At the end of October, things came to an armed confrontation, with the Ossetian side relying on the support of the Russian army.[19]

Armed conflict

Ethnic violence rose steadily in the area of the Prigorodny district, to the east of the Terek River, despite the introduction of 1,500 Soviet Internal Troops to the area.

During the summer and early autumn of 1992, there was a steady increase in the militancy of Ingush nationalists. At the same time, there was a steady increase in incidents of organized harassment, kidnapping and rape against Ingush inhabitants of North Ossetia by their Ossetian neighbours, police, security forces and militia.[3] Ingush fighters marched to take control over Prigorodny District and on the night of October 30, 1992, open warfare broke out, which lasted for a week. The first people killed were respectively Ossetian and Ingush militsiya staff (as they had basic weapons). While Ingush militias were fighting the Ossetians in the district and on the outskirts of the North Ossetian capital Vladikavkaz, Ingush from elsewhere in North Ossetia were forcibly evicted and expelled from their homes. Russian OMON forces actively participated in the fighting and sometimes led Ossetian fighters into battle.[3]

On October 31, 1992, armed clashes broke out between Ingush militias and North Ossetian security forces and paramilitaries supported by Russian Interior Ministry (MVD) and Army troops in the Prigorodny District of North Ossetia. Although Russian troops often intervened to prevent some acts of violence by Ossetian police and republican guards, the stance of the Russian peacekeeping forces was strongly pro-Ossetian,[20] not only objectively as a result of its deployment, but subjectively as well. The fighting, which lasted six days, had at its root a dispute between ethnic Ingush and Ossetians over the Prigorodnyi region, a sliver of land of about 978 square kilometers over which both sides lay claim. That dispute has not been resolved, nor has the conflict. Both sides have committed human rights violations. Thousands of homes have been wantonly destroyed, most of them Ingush. More than one thousand hostages were taken on both sides, and as of 1996 approximately 260 individuals-mostly Ingush-remain unaccounted for, according to the Procuracy of the Russian Federation. Nearly five hundred individuals were killed in the first six days of conflict. Hostage-taking, shootings, and attacks on life and property continued at least until 1996.[21] President Boris Yeltsin issued a decree that the Prigorodny district was to remain part of North Ossetia on November 2.

Casualties

Total dead as of June 30, 1994: 644.[22]

| Ossetian | 151 |

| Ingush | 302 |

| Other Nationalities | 25 |

| North Ossetian Ministry of the Interior | 9 |

| Russian Ministry of Defense | 8 |

| Russian Ministry of the Interior, Internal Troops | 3 |

| Ossetian | 9 |

| Ingush | 3 |

| Other Nationalities | 2 |

| Unknown Nationalities | 12 |

| Unified Investigative Group, Ministry of the Interior | 1 |

| Ossetian | 40 |

| Ingush | 33 |

| Other nationalities | 21 |

| Unknown nationalities | 30 |

| North Ossetian Ministry of the Interior | 9 |

| Ingush Ministry of the Interior | 5 |

| Russian Ministry of Defense | 3 |

| Russian Ministry of the Interior, Internal Troops | 4 |

| Unified Investigative Group, Russian Ministry of the Interior | 8 |

| Ossetian | 6 |

| Ingush | 3 |

| Other nationalities | 7 |

| Russian Ministry of Defense | 1 |

| Russian Ministry of the Interior, Internal Troops | 2 |

| Unified Investigative Group, Russian Ministry of the Interior | 4 |

Aftermath

According to Human Rights Watch:[3][23]

The fighting was the first armed conflict on Russian territory after the collapse of the Soviet Union. When it ended after the deployment of Russian troops, most of the estimated 34,500–64,000 Ingush residing in the Prigorodnyi region and North Ossetia as a whole had been forcibly displaced by Ossetian forces, often supported by Russian troops. There are no authoritative figures for the number of Ingush forcibly evicted from the Prigorodnyi region and other parts of North Ossetia, because there were no accurate figures for the total pre-1992 Ingush population of Prigorodnyi and North Ossetia. Ingush often lived there illegally and thus were not counted by a census. Thus the Russian Federal Migration Service counts 46,000 forcibly displaced from North Ossetia, while the Territorial Migration Service of Ingushetiya puts the number at 64,000. According to the 1989 census 32,783 Ingush lived in the North Ossetian ASSR; three years later the passport service of the republic put the number at 34,500. According to the migration service of North Ossetia, about 9,000 Ossetians were forced to flee the Prigorodnyi region and seek temporary shelter elsewhere; the majority have returned.[3][23]

It is estimated that between 1994 and 2008, around 25,000 of the Ingush people returned to Prigorodny District while some 7,500 remained in Ingushetia.[24]

On October 11, 2002, the presidents of Ingushetia and North Ossetia signed an agreement "promoting cooperation and neighborly relations".

See also

Notes

References

- ↑ "The Localized Geopolitics of Displacement and Return in Eastern Prigorodnyy Rayon, North Ossetia" (PDF). colorado.edu. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 19 July 2015.

- 1 2 Осетино‑ингушский конфликт: хроника событий (in Russian). Inca Group "War and Peace". November 8, 2008. Archived from the original on May 20, 2011. Retrieved June 4, 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Russia: The Ingush–Ossetian Conflict in the Prigorodnyi Region (Paperback) by Human Rights Watch Helsinki Human Rights Watch (April 1996) ISBN 1-56432-165-7

- ↑ Prague Watchdog Report, published July 28, 2006

- ↑ "The Secret History of Beslan". Archived from the original on 2017-04-22. Retrieved 2017-04-21.

- ↑ Schnirelmann 2006, p. 32.

- ↑ Schnirelmann 2006, p. 34.

- 1 2 Rezvan 2010, pp. 423–424.

- 1 2 3 4 Gammer 2014, p. 4.

- ↑ "Всесоюзная перепись населения 1939 года. Национальный состав населения районов, городов и крупных сел РСФСР: Чечено-Ингушская АССР >> Пригородный" [All-Union Population Census of 1939. National composition of the population of districts, cities and large villages of the RSFSR: Chechen-Ingush ASSR >> Prigorodny]. Demoskop Weekly (in Russian). 1939. Retrieved 2023-11-10.

- ↑ Schnirelmann 2006, p. 50.

- 1 2 Rezvan 2010, p. 424.

- ↑ Tishkov 1997, p. 163.

- ↑ Nekrich 1978, p. 131.

- ↑ Schnirelmann 2006, p. 144.

- ↑ Schnirelmann 2006, p. 147.

- ↑ Zdravosmyslov 1998, p. 30.

- ↑ Smith 2009, p. 108.

- ↑ Schnirelmann 2006, p. 154.

- ↑ A. Dzadziev. The Ingush–Ossetian conflict: The Roots and the Present Day // Journal of Social and Political Studies. 2003, _ 6 (24)

- ↑ "Russia". Archived from the original on 2017-02-07. Retrieved 2019-09-05.

- ↑ Raion Chrezvychainogo Polozheniya (Severnaya Osetiya I Ingushetiya), (The Region of Emergency Rule: North Ossetia and Ingushetiya,) Vladikavkaz, North Ossetia, 1994, p. 63. This compilation of reports, statistics, and documents is published by the Temporary Administration.

- 1 2 "Russia". hrw.org. Archived from the original on 25 March 2017. Retrieved 28 June 2015.

- ↑ "Russian Federation: Imminent forcible eviction in Ingushetia" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-04-22. Retrieved 2017-08-26.

Sources

- Deutch, Mark (2007-02-11). "Осетино-ингушский конфликт: у каждой из сторон – своя правда" [Ossetian-Ingush conflict: each side has its own truth]. Nezavisimaya gazeta (in Russian). Moscow.

- Gammer, Moshe (2014-09-22). "Separatism in the Northern Caucasus". Caucasus Survey. Leiden; Paderborn: Brill; Schöningh. 1 (2): 1–10 (37–47).

- Nekrich, Аlexander (1978). Наказанные народы [The Punished peoples] (in Russian). New York: Khronika Press. pp. 1–170.

- Rezvan, Babak (2010-01-01). Asatrian, Garnik; et al. (eds.). "The Ossetian-Ingush Confrontation: Explaining a Horizontal Conflict". Iran and the Caucasus. Leiden; Boston: Brill. 14: 419–430. doi:10.1163/157338410X12743419190502. eISSN 1573-384X. ISSN 1609-8498.

- Rezvani, Babak (2015-01-27). Conflict and Peace in Central Eurasia. International Comparative Social Studies. Vol. 31. Leiden; Boston: Brill. pp. 1–361. ISBN 978-90-04-27636-9.

- Schnirelmann, Victor (2006). Kalinin, Ilya (ed.). Быть Аланами: Интеллектуалы и политика на Северном Кавказе в XX веке [To be Alans: Intellectuals and Politics in the North Caucasus in the 20th Century] (in Russian). Moscow: Novoe literaturnoe obozrenie. pp. 1–348. ISBN 5-86793-406-3. ISSN 1813-6583.

- Smith, Sebastian (2009). Allah's Mountains: The Battle for Chechnya (3rd ed.). London; New York: Tauris Parke Paperbacks. pp. 1–288.

- Tishkov, Valery (1997). Ethnicity, Nationalism and Conflict in and After the Soviet Union: The Mind Aflame. London: SAGE. pp. 1–334. ISBN 0761951857.

- Tishkov, Valery (2013). "Социально-политическая ситуация в 1940–1990-е годы" [Socio-political situation in the 1940s–1990s]. In Albogachieva, Makka; Martazanov, Arsamak; Solovyeva, Lyubov (eds.). Ингуши [The Ingush] (in Russian). Moscow: Nauka. pp. 87–99.

- Tsutsiev, Arthur (1998). Осетино-ингушский конфликт (1992—...): его предыстория и факторы развития. Историко-социологический очерк [Ossetian-Ingush conflict (1992–...): its background and development factors. Historical and sociological essay] (in Russian). Moscow: ROSSPEN. pp. 1–200. ISBN 5-86004-178-0.

- Tumakov, Denis V. (2022). "Осетино-ингушский вооружённый конфликт 1992 год" [The Ossetian-Ingush armed conflict of 1992 as covered by the Russian central press]. Historia provinciae (in Russian). 6 (2): 439–484. doi:10.23859/2587-8344-2022-6-2-3. eISSN 2587-8344.

- Zdravosmyslov, Andrey (1998). Осетино-Ингушский конфликт: Перспективы выхода из тупиковой ситуации [Ossetian-Ingush conflict: Prospects for breaking the deadlock] (in Russian). Moscow: ROSSPEN. pp. 1–127. ISBN 5-86004-177-2.