| Pepi II Neferkare | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Alabaster statue of Ankhesenmeryre II and her son Pepi II. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pharaoh | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Reign | 2278–after 2247 BC, probably either c. 2216 or c. 2184 BC[1][2] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | Merenre Nemtyemsaf I | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Successor | Merenre Nemtyemsaf II | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Consort | Neith, Iput II, Ankhesenpepi III, Ankhesenpepi IV, Udjebten, and Meritites IV | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Father | Merenre Nemtyemsaf I or, less probably, Pepi I Meryre | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mother | Ankhesenpepi II | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | 2284 BC | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | after 2247 BC, probably c. 2216 BC or c. 2184 BC (older than 37, probably aged 68–100) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Burial | Pyramid of Pepi II in Saqqara | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Monuments | Pyramid of Pepi II | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dynasty | 6th Dynasty | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Pepi II Neferkare (2284 BC – after 2247 BC, probably either c. 2216 or c. 2184 BC[2][note 1]) was a pharaoh of the Sixth Dynasty in Egypt's Old Kingdom who reigned from c. 2278 BC. His second name, Neferkare (Nefer-ka-Re), means "Beautiful is the Ka of Re". He succeeded to the throne at age six, after the death of Merenre I.

Pepi II's reign marked a sharp decline of the Old Kingdom. As the power of the nomarchs grew, the power of the pharaoh declined. With no dominant central power, local nobles began raiding each other's territories and the Old Kingdom came to an end within a couple of years after the close of Pepi II's reign.

Early reign

He was traditionally thought to be the son of Pepi I and Queen Ankhesenpepi II, but the South Saqqara Stone annals record that Merenre had a minimum reign of 11 years. Several 6th Dynasty royal seals and stone blocks – the latter of which were found within the funerary temple of Queen Ankhesenpepi II, the known mother of Pepi II – were discovered in the 1999–2000 excavation season at Saqqara, which demonstrate that she also married Merenre after Pepi I's death and became this king's chief wife.[5] Inscriptions on these stone blocks give Ankhesenpepi II the royal titles of: "King's Wife of the Pyramid of Pepy I, King's Wife of the Pyramid of Merenre, King's Mother of the Pyramid of Pepy II".[6] Therefore, today, many Egyptologists believe that Pepi II was likely Merenre's own son.[7] Pepi II would, therefore, be Pepi I's grandson while Merenre was, most likely, Pepi II's father since he is known to have married Pepi II's known mother, Queen Ankhesenpepi II.

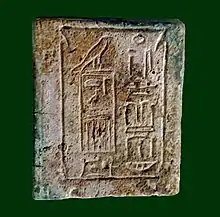

His mother Ankhesenpepi II (Ankhesenmeryre II) most likely ruled as regent in the early years of his reign. She may have been helped in turn by her brother Djau, who was a vizier under the previous pharaoh. An alabaster statuette in the Brooklyn Museum depicts a young Pepi II, in full kingly regalia, sitting on the lap of his mother. Despite his long reign, this piece is one of only three known sculptural representations in existence of this particular king. Some scholars have taken the relative paucity of royal statuary to suggest that the royal court was losing the ability to retain skilled artisans.

A glimpse of the personality of the pharaoh while he was still a child can be found in a letter he wrote to Harkhuf, a governor of Aswan and the head of one of the expeditions he sent into Nubia. Sent to trade and collect ivory, ebony, and other precious items, he captured a pygmy. News of this reached the royal court, and an excited young king sent word back to Harkhuf that he would be greatly rewarded if the pygmy were brought back alive, where he would have likely served as an entertainer for the court. This letter was preserved[8] as a lengthy inscription on Harkhuf's tomb, and has been called the first travelogue.[9]

Family

Over his long life Pepi II had several wives, including:

- Neith – She was the mother of Pepi's successor Merenre Nemtyemsaf II.[10] She may be a daughter of Ankhesenpepi I and hence also Pepi II's cousin and half-sister.[11]

- Iput II – A half-sister of Pepi II.[10]

- Ankhesenpepi III She was the daughter of Merenre Nemtyemsaf I and hence a granddaughter of Pepi I.[10][11]

- Ankhesenpepi IV – The mother of King Neferkare according to texts in her tomb. It is not known which Neferkare as there are several kings with that name during the First Intermediate Period.[10] His name may be Neferkare Nebi.[11]

- Udjebten[10] She was also a daughter of Pepi I.[11]

- Meritites IV - Originally thought to be a wife of Pepi I, she is now known to have been one of Pepi II's consorts, and a daughter of Pepi I.

Of these queens, Neith, Iput, and Udjebten each had their own minor pyramids and mortuary temples as part of the king's own pyramid complex in Saqqara. Queen Ankhesenpepi III and Meritites IV were buried in pyramids near the pyramid of Pepi I Meryre, and Ankhesenpepi IV was buried in a chapel in the complex of Queen Udjebten.[10]

Two more sons of Pepi II are known: Nebkauhor-Idu and Ptahshepses (D).[10]

Foreign policy

Pepi II seems to have carried on foreign policy in ways similar to that of his predecessors. Copper and turquoise were mined at Wadi Maghareh in the Sinai, and alabaster was quarried from Hatnub. He is mentioned in inscriptions found in the Phoenician city of Byblos.[12]

In the south, the trade relations consist of caravans trading with the Nubians. Harkhuf was a governor of Upper Egypt, who led several expeditions under Merenre and Pepi II. His last expedition was a trip to a place called Iam.[13] Harkhuf brought back with him what his correspondence with the young pharaoh referred to as a dwarf, apparently a pygmy.[14] Egypt received goods such as incense, ebony, animal skins, and ivory from Nubia.[15] The Western desert was known to have extensive caravan routes. Some of these routes allowed for trade with the Kharga Oasis, the Selima Oasis, and the Dakhla Oasis.[15]

King Neferkare and General Sasenet

Only a small number of pharaohs were immortalized in ancient fiction, Pepi II may be among them. In the tale of "King Neferkare and General Sasenet", three fragments of a papyrus dating from the late New Kingdom (although the story may have been composed earlier),[16] report clandestine nocturnal meetings with a military commander – a General Sasenet or Sisene. Some have suggested this reflects a homosexual relationship although it is disputed that the text relates to Pepi II at all.[17] Some, like R. S. Bianchi, think that it is a work of archaizing literature and dates to the 25th Dynasty referring to Shabaka Neferkare, a Kushite pharaoh.[18]

Decline of the Old Kingdom

The decline of the Old Kingdom arguably began before the time of Pepi II, with nomarchs (regional representatives of the king) becoming more and more powerful and exerting greater influence. Pepi I, for example, married two sisters who were the daughters of a nomarch and later made their brother a vizier. Their influence was extensive, both sisters bearing sons who were chosen as part of the royal succession: Merenre Nemtyemsaf I and Pepi II himself.

Increasing wealth and power appears to have been handed over to high officials during Pepi II's reign. Large and expensive tombs appear at many of the major nomes of Egypt, built for the reigning nomarchs, the priestly class and other administrators. Nomarchs were traditionally free from taxation and their positions became hereditary. Their increasing wealth and independence led to a corresponding shift in power away from the central royal court to the regional nomarchs.

Later in his reign, it is known that Pepi divided the role of vizier so that there were two viziers: one for Upper Egypt and one for Lower, a further decentralization of power away from the royal capital of Memphis. Further, the seat of vizier of Lower Egypt was moved several times. The southern vizier was based at Thebes.

Reign length

Pepi II is often mentioned as the longest reigning monarch in history, due to a 3rd-century BC account of Ancient Egypt by Manetho, which accords the king a reign of 94 years; this has, however, been disputed by some Egyptologists due to the absence of attested dates known for Pepi II after his 31st count (Year 62 if biennial) such as Hans Goedicke (1926-2015) and Michel Baud note. Ancient sources upon which Manetho's estimate is based are long lost, and could have resulted from a misreading on Manetho's behalf (see von Beckerath).[19] The Turin canon attributes 90+ [X] years of reign to Pepi II, but this document dates to the time of Ramesses II, 1,000 years after Pepi II's death.

At the present time, the latest written source contemporary with Pepi II dates from the "Year after the 31st Count, 1st Month of Shemu, day 20" from Hatnub graffito No.7 (Spalinger, 1994),[20] which implies, assuming a biennial cattle count system, that this king had a reign of at least 62 complete or partial years. Therefore, some Egyptologists suggest instead that Pepi II reigned no more than 64 years.[21][4] This is based on the complete absence of higher attested dates for Pepi beyond his Year after the 31st Count (Year 62 on a biannual cattle count). A previous suggestion by Hans Goedicke that the Year of the 33rd Count appears for Pepi II in a royal decree for the mortuary cult of Queen Udjebten was withdrawn by Goedicke himself in 1988 in favour of a reading of "the Year of the 24th Count" instead.[20] Goedicke writes that Pepi II is attested by numerous year dates until the Year of his 31st count which strongly implies that this king died shortly after a reign of about 64 years.[22] Other scholars note that the lack of contemporary sources dated after his 62nd year on the throne does not preclude a much longer reign, in particular since the end of Pepi II's reign was marked by a sharp decline in the fortunes of the Old Kingdom pharaohs who succeeded him.[2]

The Egyptologist David Henige states while there have been examples of kinglists where rulers were ascribed reigns as long as that assigned to Pepi II, "often exceeding 100 years, but these are invariably rejected as mythical", the problems inherent in dating Pepi II's reign are many since:

...a hyperextended duration [for Pepi II's reign] is not really necessary to bring Old Kingdom chronology into some equilibrium with other chronologies. For Mesopotamia from at least this early until virtually the Persian conquest, numerous localized synchronisms play vital roles in absolute dating, but seldom affect the duration of individual dynasties. Not only is Old Kingdom Egypt well outside any "synchronism zone" but, as it happens, since Pepy [II] was the last substantive ruler of Egypt before a period of political and chronological chaos...there are no awkward ramifying effects by reducing his reign by twenty or thirty years, a period that can simply be added on to the First Intermediate Period.[23]

Henige himself is somewhat skeptical of the 94 year figure assigned to Pepi II[24] and follows Naguib Kanawati's 2003 suggestion that this king's reign was most probably much shorter than 94 years.[25]

This situation could have produced a succession crisis and led to a stagnation of the administration, centered on an absolute yet aging ruler who was not replaced because of his perceived divine status. A later, yet better documented, example of this type of problem is the case of the long reigning Nineteenth Dynasty pharaoh Ramesses II and his successors.

It has been proposed that the 4.2 kiloyear event be linked to the collapse of the Old Kingdom in Egypt, though current resolution of evidence is not sufficient to make an assertion.[26][27]

The Ipuwer Papyrus

In the past it had been suggested that Ipuwer the sage served as a treasury official during the last years of Pepi II Neferkare's reign.[28][29] The Ipuwer Papyrus was thought by some to describe the collapse of the Old Kingdom and the beginning of the Dark Age, known to historians as the First Intermediate Period.[30] It had been claimed that archaeological evidence from Syrian button seals supported this interpretation.[31] The admonitions may not be a discussion with a king at all however. Otto was the first to suggest that the discussion was not between Ipuwer and his king, but that this was a discussion between Ipuwer and a deity. Fecht showed through philological interpretation and revision of the relevant passages that this is indeed a discussion with a deity.[32] Modern research suggests that the papyrus dates to the much later 13th Dynasty, with part of the papyrus now thought to date to the time of Pharaoh Khety, and the admonitions of Ipuwer actually being addressed to the god Atum, not a mortal king.[29] The admonitions are thought to harken back to the First Intermediate Period and record a decline in international relations and a general impoverishment in Egypt.[33]

Pyramid complex

The pyramid complex was called

The complex consists of Pepi's pyramid with its adjacent mortuary temple. The pyramid contained a core made of limestone and clay mortar. The pyramid was encased in white limestone. An interesting feature is that after the north chapel and the wall was completed, the builders tore down these structures and enlarged the base of the pyramid. A band of brickwork reaching to the height of the perimeter wall was then added to the pyramid. The purpose of this band is not known. It has been suggested that the builders wanted the structure to resemble the hieroglyph for pyramid,[35] or that possibly the builders wanted to fortify the base of the structure due to an earthquake.[34]

The burial chamber had a gabled ceiling covered by painted stars. Two of the walls consisted of large granite slabs. The sarcophagus was made of black granite and inscribed with the king's name and titles. A canopic chest was sunk in the floor.[35]

To the northwest of the pyramid of Pepi II, the pyramids of his consorts Neith and Iput were built. The pyramid of Udjebten is located to the south of Pepi's pyramid. The Queen's pyramids each had their own chapel, temple and a satellite pyramid. Neith's pyramid was the largest and may have been the first to be built. The pyramids of the Queens contained Pyramid Texts.[34][35]

The mortuary temple adjacent to the pyramid was decorated with scenes showing the king spearing a hippopotamus and thus triumphing over chaos. Other scenes include the sed festival, a festival of the god Min and scenes showing Pepi executing a Libyan chieftain, who is accompanied by his wife and son. The scene with the Libyan chief is a copy from Sahure's temple.[34][35] A courtyard was surrounded by 18 pillars which were decorated with scenes of the king in the presence of gods.[35]

Despite the longevity of Pepi II, his pyramid was no larger than those of his predecessors at 150 cubits (78.5 metres (258 ft)) per side at the base and 100 cubits (52.5 metres (172 ft)) high and followed what had become the 'standard format'. The pyramid was made from small, local stones and infill, covered with a veneer of limestone. The limestone was removed and the core has slumped. The causeway was approximately 400 metres (1,300 ft) long and the valley temple was on the shores of a lake, long since gone.

The site is located at 29°50′25″N 31°12′49″E / 29.84028°N 31.21361°E.

Excavation

The complex was first investigated by John Shae Perring, but it was Gaston Maspero who first entered the pyramid in 1881. Gustave Jéquier was the first to investigate the complex in detail between 1926 and 1936.[34][36] Jéquier was the first excavator to start actually finding any remains from the tomb reliefs,[37] and he was the first to publish a thorough excavation report on the complex.[38]

Portraiture

A statue which is now in the Brooklyn Museum depicts Queen Ankhenesmerire II with her son Pepi II on her lap. Pepi II wears the royal nemes headdress and a kilt. He is shown at a much smaller scale than his mother. This difference in size is atypical because the king is usually shown larger than others. The difference in size may refer to the time period when his mother served as a regent. Alternatively the statue may depict Ankhenesmerire II as the divine mother.[39]

Another statue of Pepi II is now in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo (JE 50616). The king is shown as a naked child. The depiction of the king at such a young age may refer to the age he came to the throne.[40]

Successors

There are few official contemporary records or inscriptions of Pepi's immediate successors. According to Manetho and the Turin King List, he was succeeded by his son Merenre Nemtyemsaf II, who reigned for just over a year.[41] It is then believed that he was in turn succeeded by the obscure pharaoh Neitiqerty Siptah, though according to popular tradition (as recorded by Manetho two millennia later) he was succeeded by Queen Nitocris, who would be the first female ruler of Egypt.[42]

This was the end of the Old Kingdom of Egypt, a prelude to the roughly 200-year span of Egyptian history known as the First Intermediate Period.[42]

See also

Notes

- ↑ The year 2247 BC is a conservative lower estimate based on the number of cattle counts (thirty-one) that occurred during the pharaoh's reign, if counts are assumed to have been taken annually. Though Egyptian cattle counts are most often thought to have taken place biennially, late Old Kingdom reigns might have been an exception to the rule.[4] If they indeed were taken every two years, then the pharaoh reigned for about 62 years, till around 2212 BC. Pepi II is often mentioned as the longest-reigning monarch in History based on accounts from the late 2nd millennium BC Turin canon and the 3rd century BC history of Egypt by Manetho. Earlier sources upon which Manetho's estimate and the Turin canon are based are probably lost.

References

- ↑ Clayton, Peter A. Chronicle of the Pharaohs: The Reign-by-Reign Record of the Rulers and Dynasties of Ancient Egypt. p.64. Thames & Hudson. 2006. ISBN 0-500-28628-0

- 1 2 3 Darell D. Baker: The Encyclopedia of the Pharaohs: Volume I – Predynastic to the Twentieth Dynasty 3300 – 1069 BC, Stacey International, ISBN 978-1-905299-37-9, 2008

- ↑ "VIth Dynasty". Archived from the original on 2009-04-17. Retrieved 2009-07-22.

- 1 2 Michel Baud, "The Relative Chronology of Dynasties 6 and 8" in Ancient Egyptian Chronology (Leiden, 2006) pp.152–57

- ↑ A. Labrousse and J. Leclant, "Une épouse du roi Mérenrê Ier: la reine Ankhesenpépy I", in M. Barta (ed.), Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2000, Prague, 2000. pp.485–490

- ↑ Labrousse and J. Leclant, pp.485–490

- ↑ A. Labrousse and J. Leclant, "Les reines Ânkhesenpépy II et III (fin de l'Ancien Empire): campagnes 1999 et 2000 de la MAFS", Compte-rendu de l'Académie des inscriptions et belles-lettres/, (CRAIBL) 2001, pp.367–384

- ↑ Tomb inscriptions of Harkhuf

- ↑ Omar Zuhdi, Count Harkhuf and The Dancing Dwarf, KMT 16 Vol:1, Spring 2005, pp.74–80

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Dodson, Aidan and Hilton, Dyan. The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson. 2004. pp 70–78, ISBN 0-500-05128-3

- 1 2 3 4 Tyldesley, Joyce, Chronicle of the Queens of Egypt. Thames & Hudson. 2006. pp 61–63, ISBN 0-500-05145-3

- ↑ G. Edward Brovarski, "First Intermediate Period, overview" in Kathryn A. Bard and Steven Blake Shubert, eds. Encyclopedia of the Archeology of Ancient Egypt(New York: Routledge, 1999), 46.

- ↑ Wente, Edward, Letters from Ancient Egypt, Scholars Press, 1990. ISBN 1-55540-473-1, pp 20–21

- ↑ Pascal Vernus, Jean Yoyotte, The Book of the Pharaohs, Cornell University Press 2003. ISBN 0-8014-4050-5. p.74

- 1 2 Shaw, Ian. The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press. 2000. ISBN 0-19-280458-8, pp 116–117

- ↑ Lynn Meskell, Archaeologies of social life: age, sex, class et cetera in ancient Egypt, Wiley-Blackwell, 1999, p.95

- ↑ Greenberg, David, The Construction of Homosexuality, 1988; Parkinson, R.B.,'Homosexual' Desire and Middle Kingdom Literature Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, vol. 81, 1995, p. 57-76

- ↑ Robert Steven Bianchi, Daily Life Of The Nubians, Greenwood Press, 2004. p.164

- ↑ Jürgen von Beckerath, Chronologie des pharaonischen Ägypten (Mainz 1997), p151

- 1 2 Anthony Spalinger, Dated Texts of the Old Kingdom, SAK 21, 1994, p.308

- ↑ Hans Goedicke, The Death of Pepi II-Neferkare" in Studien zur Altägyptischen Kultur 15, (1988), pp.111–121

- ↑ Goedicke, 1988, pp.111–121

- ↑ David Henige (University of Wisconsin), How long did Pepy II reign?, GM 221 (2009), p. 44

- ↑ Henige, GM 221, p.48

- ↑ Naguib Kanawati, Conspiracies in the Egyptian Palace, Unis to Pepy I (London: Routledge, 2003), 4.170.

- ↑ Ann Gibbons, How the Akkadian Empire Was Hung Out to Dry, Science 20 August 1993: 985. Online citation

- ↑ Jean-Daniel Stanley, Michael D. Krom, Robert A. Cliff, Jamie C. Woodward, Short contribution: Nile flow failure at the end of the Old Kingdom, Egypt: Strontium isotopic and petrologic evidence, Geoarchaeology, Volume 18, Issue 3, pages 395–402, March 2003 Online citation

- ↑ Encyclopaedia Britannica, inc (2002). The new encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopaedia Britannica. ISBN 978-0-85229-787-2.

- 1 2 Williams, R. J. (1981), "The Sages of Ancient Egypt in the Light of Recent Scholarship", Journal of the American Oriental Society, 101 (1): 1–19, doi:10.2307/602161, JSTOR 602161

- ↑ Barbara Bell, The Dark Ages in Ancient History. I. The First Dark Age in Egypt, American Journal of Archaeology, Vol. 75, No. 1 (Jan., 1971), pp. 1–26 JSTOR

- ↑ Thomas L. Thompson (2002). The Historicity of the Patriarchal Narratives: The Quest for the Historical Abraham. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-1-56338-389-2.

- ↑ Winfried Barta, Das Gespräch des Ipuwer mit dem Schöpfergott, Studien zur Altägyptischen Kultur, Bd. 1 (1974), pp. 19–33

- ↑ Mumford, Gregory (2006), "Tell Ras Budran (Site 345): Defining Egypt's Eastern Frontier and Mining Operations in South Sinai during the Late Old Kingdom (Early EB IV/MB I)", Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, 342 (342): 13–67, doi:10.1086/BASOR25066952, JSTOR 25066952, S2CID 163484022

- 1 2 3 4 5 Verner, Miroslav. The Pyramids: The Mystery, Culture, and Science of Egypt's Great Monuments. Grove Press. 2001 (1997). pp 362 – 372, ISBN 0-8021-3935-3

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Lehner, Mark. The Complete Pyramids. Thames & Hudson. 2008 (reprint). pp 161–163, ISBN 978-0-500-28547-3

- ↑ Shaw, Ian. and Nicholson, Paul. The Dictionary of Ancient Egypt. p. 220. The British Museum Press, 1995.

- ↑ Shaw and Nicholson, p.220

- ↑ Jéqier, Gustav. Le monument funéraire de Pepi II. 3 volumes, Cairo, 1936–41.

- ↑ Gay Robins, The Art of Ancient Egypt, Harvard University Press, 1997, pp 66–67, ISBN 978-0-674-00376-7

- ↑ N. Grimal, A history of ancient Egypt, Wiley-Blackwell, 1994, pg 98

- ↑ Dodson, Aidan and Hilton, Dyan. The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson. 2004. p 288, ISBN 0-500-05128-3

- 1 2 Shaw, Ian. The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press. 2000. pp 116–117, ISBN 0-19-280458-8

Bibliography

- Dodson, Aidan. Hilton, Dyan. 2004. The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt, Thames & Hudson

- Dodson, Aidan. "An Eternal Harem: Tombs of the Royal Families of Ancient Egypt. Part One: In the Beginning". KMT. Summer 2004.

- Shaw, Ian. Nicholson, Paul. 1995. The Dictionary of Ancient Egypt, Harry N. Abrams, Inc. Publishers.

- Spalinger, Anthony. Dated Texts of the Old Kingdom, SAK 21, (1994), pp. 307–308

- Oakes, Lorna and Lucia Gahlun. 2005. Ancient Egypt. Anness Publishing Limited.

- Perelli, Rosanna, "Statuette of Pepi II" in Francesca Tiradriti (editor), The Treasures of the Egyptian Museum, American University in Cairo Press, 1999, p. 89.