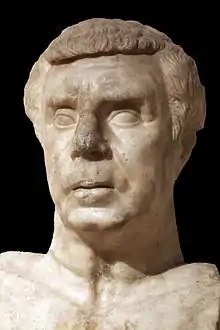

Lucius Munatius Plancus (c. 87 BC – c. 15 BC) was a Roman senator, consul in 42 BC, and censor in 22 BC with Paullus Aemilius Lepidus. He is one of the classic historical examples of men who have managed to survive very dangerous circumstances by constantly shifting their allegiances. Beginning his career under Julius Caesar, he allied with his assassin Decimus Junius Brutus in 44 BC, then with the Second Triumvirate in 43 BC, joining Mark Antony in 40 BC, and deserting him for Octavian in 32 BC. He also founded the cities of Augusta Raurica (now Augst) and Lugdunum (now Lyon). His tomb is still visible at Gaeta.

Early career

Plancus was born in Tibur, the son of his homonymous father, of whom very little is known. He had three brothers and a sister: two of the brothers pursued public lives, one ascending to the praetorship and the other reaching the plebeian tribunate. He must have entered public life with election as quaestor some time before 54 BC.[1]

More concrete information on Plancus' career only appears when he became one of Julius Caesar's legates during the Gallic Wars: he served under Caesar in Gaul from 54 BC through to the start of Caesar's civil war in January 49 BC.[2] At the start of the civil war, he joined with Caesar against Pompey; he served under Caesar with Gaius Fabius (the praetor in 58 BC) during Caesar's Illerda campaign.[3] He sailed with Caesar to Africa in 47 BC;[4] this year he likely was one of the praetors.[5] When Caesar left for Spain in 45 BC, Plancus was appointed one of the prefects of the city in place of quaestors and aediles who had not been elected that year.[6] Upon Caesar's return from Spain, he appointed Plancus governor of Transalpine Gaul pro consule in early 44 BC.[7]

Transition to empire

Upon the assassination of Julius Caesar on 15 March 44 BC, Plancus was still in Rome. In the immediate aftermath of the deed, he – like many other Caesarians – supported amnesty for the tyrannicides and departed for his province.[9] He must have also supported preservation of Caesar's acta, which would have been in service to his own career as well, as Caesar had before his death designated Plancus as one of the consuls for 42 BC.[10] There, he raised more men while keeping a close eye on political developments in the city. He also campaigned in Raetia, winning some victories, for which he was proclaimed imperator, by September.[11]

Formation of the triumvirate

A political crisis unfolded over the year 44 BC. Plancus and Decimus Junius Brutus were the governors of Transalpine and Cisalpine Gaul, respectively.[12] Mark Antony, then one of the consuls, used soldiers to intimidate the assembly in passing a law in June transferring those provinces to himself. Antony left on 28 November 44 BC seeking to take those provinces from their governors.[13] Soon afterwards, Cicero was writing to the governors already stationed there seeking military support to resist Antony's assumption of the provinces; he wrote both to Plancus and Decimus Brutus.[13] On 20 December 44 BC, the senate decreed that the existing governors should resist Antony by force if necessary.[10] His funerary inscription attests that around this time he founded the cities of Augusta Raurica (44 BC) and Lugdunum (Lyon) (43 BC)[14] and in June 43 BC, some letters attest to his passage through the village of Cularo (present Grenoble) in the Dauphiné Alps.[15]

Plancus was slow to respond to the senate's call to arms. Responding months later in March 43 BC, he publicly warned against the rush to war. Privately, he wrote to Cicero that he was preparing his legions and auxiliaries.[16] While both sides were preparing forces, it is clear that Plancus was entertaining offers from both Cicero in the senate and Antony. Around the same time a further message arrived from Plancus publicly declaring for the senate, Antony asserted in a letter to Rome that he had Plancus' support. Plancus defended his caution with the argument that declaring too rashly before preparations would have meant swift consequences like those that befell Decimus Brutus (then besieged in Mutina).[17]

The senate sent three commanders, the two consuls and Caesar's heir Octavian after Antony. They defeated Antony on 21 April 43 BC at the Battle of Mutina; but both consuls were killed. After the battle, Plancus sought to persuade Marcus Aemilius Lepidus to join with the senate. After Lepidus joined Antony on 29 May, Plancus retreated across the river Isara and sought to join forces with Decimus, his co-consul designate for 42 BC and a high-profile tyrannicide.[18] Lepidus sent a message to the senate blaming his soldiers for forcing his defection; at the same time, Octavian refused to cooperate with Decimus Brutus, ostensibly due to his soldiers refusing to help an assassin of Caesar. In the last letter from Plancus to Cicero, he castigates Cicero's strategy of elevating Octavian, who was by then well known to be seeking one of the vacant consulships and, by inaction, allowing Antony to regain strength.[19]

Three weeks after this last letter, Octavian's soldiers marched on Rome and engineered his election as suffect consul with Quintus Pedius. Pedius' passage of the lex Pedia which sentenced the tyrannicides to exile in absentia changed Plancus' calculations; after a few months of cooperation with Decimus, he broke off. While Antony was angry at Plancus for his having sided with the senate, he was able to parley his five legions and Gallic cavalry into keeping his consulship and a triumph.[20]

Under the Triumvirate

After Octavian joined with Antony and Lepidus to form the Second Triumvirate in 43 BC through passage of the lex Titia,[21] they and their main allies all gave one close family member or friend to the proscriptions. Plancus is said to have put his brother – Lucius Plotius Plancus – on the death lists.[5][22] For the victories he won over the Gauls in Raetia, he celebrated a triumph on 29 December 43 BC.[5][23] Thereafter, he held the consulship of 42 BC with Lepidus. During his consulship, he brought legislation to overturn some of the names on the Second Triumvirate's proscription lists and distributed land to veterans near Beneventum.[24]

The next year, he continued supervising colonisation near Beneventum and, during the Perusine War, assisted Lucius Antony in defeating one of Octavian's legions.[25] After the defeat of the plot, he fled with Antony's wife Fulvia to Greece. After the peace of Brundisium in 40 BC healed the rift between Octavian and Antony, he was assigned to Asia pro consule.[26] He likely stayed in Asia through 38 BC.[27]

Service under and defection from Antony

During Mark Antony's expedition in 36 BC, to Armenia and Parthia to avenge Crassus' death from 17 years earlier, he was proconsular governor (or perhaps legate) of Syria.[28] He was blamed for ordering the execution of Sextus Pompey in Antony's name after Sextus was caught attempting to flee to Parthia via Asia.[29]

Plancus deserted Antony's side in 32 BC. The reasons are unclear. Ronald Syme speculated that he did so merely because he calculated Octavian was in the stronger position. However, Octavian's victory was likely not yet clear in 32 BC.[30] Plancus and his nephew Marcus Titius were instrumental in securing for Octavian the contents of Antony's will, which gravely damaged Antony's reputation.[31][32] Complimentary sources, such as Horace's Ode 1.7, praise Plancus for having realised the falsity of Antony's promises and having returned virtuously to the side of Rome and Italy.[31]

Under Augustus

In January 27 BC, Plancus, as one of the senior ex-consuls, brought a motion suggestion that Octavian adopt the title Augustus.[33]

His last political office was held in 22 BC, after Augustus appointed him and Aemilius Lepidus Paullus as censors.[34] Their censorship is famous not for any remarkable deeds, but because it was the last time that such magistrates were appointed. According to Velleius Paterculus' Roman history,[35] it was a shame for both of the senators:

the censorship of Plancus and Paullus, which, exercised as it was with mutual discord, was little credit to themselves or little benefit to the state, for the one lacked the force, the other the character, in keeping with the office; Paullus was scarcely capable of filling the censor's office, while Plancus had only too much reason to fear it, nor was there any charge which he could make against young men, or hear others make, of which he, old though he was, could not recognize himself as guilty

In Suetonius' Life of Nero,[36] we read that the emperor Nero's grandfather, Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus, whose wife was Antonia Major, daughter of Mark Antony, "was haughty, extravagant, and cruel, and when he was only an aedile, forced the censor Lucius Plancus to make way for him on the street"; the story seems to hint at the poor reputation Plancus held after his censorship.

Legacy

Tomb and family

Plancus died in Gaeta and is one of the very few important Roman historical figures whose tomb has survived and is identifiable, although his body has long since vanished. The Mausoleum of Plancus, a massive cylindrical tomb now much restored (and consecrated to the Virgin Mary in the late 19th century), is in Gaeta, on a hill overlooking the sea: it houses a small permanent exhibit in honor of him.

Plancus' children included one son and one daughter. His son was Lucius Munatius Plancus (ca 45 BC - aft. 14), consul in AD 13 and legate in 14, who married Aemilia Paulla, daughter of Paullus Aemilius Lepidus and wife Cornelia. In AD 14 the son went to Germany to help suppress the Rhine legions' mutiny with little success.[37] Plancus' daughter Munatia Plancina (ca 35 BC - aft. 20) married the infamous Gnaeus Calpurnius Piso, and they had two sons, Gnaeus and Marcus Piso. Plancina and her husband were accused of poisoning Germanicus.[38] In Syria, she offended common sensibility by attending cavalry exercises and hired a notorious poisoner.[39] After the death of Germanicus, Piso and Plancina first tried to take back control of the province, then slowly returned to Rome, where they were put on trial for fomenting civil war and for poisoning Germanicus. Eventually Livia intervened to save Plancina and she was pardoned. Many years later in AD 34 she was again prosecuted and driven to suicide.[40] Her two sons survived her. Gnaeus Piso had to change his name to Lucius Piso, but later became governor of Africa in AD 39 under Caligula.[41] The charges against Marcus Piso were dismissed by Tiberius.[42]

Reputation

Plancus has a negative reputation in both ancient texts and modern scholarship.[43][44] Cicero, writing a letter in late 44 BC told him that he was "too much as the service of the times".[45] The specific meaning of Cicero's words are debated; Mitchell argues that the times in that sentence refers to Caesar's dominatio over the state rather than a generalised lack of principle.[46]

The history of Velleius Paterculus was very hostile to Plancus. He blamed Plancus for his brother's death and paints his defection from Antony in 32 BC in terms being a pathological traitor with no political principles.[47] He also painted Plancus as a fawning flatterer of Cleopatra, as greedy, and as furthering Antony's poor judgement.[48] For his triumph over the Gauls in 43 BC. the soldiers coined a pun on him alluding that he did not celebrate over the Gauls but over his brother.[44] Velleius' account may be derived from Gaius Asinius Pollio's speeches; criticism of Plancus is usually coupled with praise with Pollio.[49]

Ronald Syme, in Roman Revolution memorably savaged him: "A nice calculation of his own interests and an assiduous care for his own safety carried him through well-timed treacheries to a peaceful old age".[50] While more recent scholarship has perhaps softened slightly, Plancus' career is still largely seen in terms of flexibly adapting to prevailing circumstances out of self-interest.[51]

References

- Citations

- ↑ "L. Munatius (30) L. f. L. n. Cam.? Plancus". Digital Prosopography of the Roman Republic. Retrieved 2022-07-17.

- ↑ Broughton 1952, pp. 593, 226 (54 BC), 231 (53 BC), 239 (52 BC), 244 (51 BC), 253 (50 BC).

- ↑ Broughton 1952, p. 268.

- ↑ Broughton 1952, p. 291.

- 1 2 3 Richardson, Cadoux & Badian 2012.

- ↑ Broughton 1952, p. 313.

- ↑ Broughton 1952, p. 329.

- ↑ "Kein Basler: Lucius Munatius Plancus". www.staatskanzlei.bs.ch (in German). Retrieved 2021-05-10.

- ↑ Mitchell 2019, p. 172, citing Plut. Brut. 19.1.

- 1 2 Mitchell 2019, p. 172.

- ↑ Broughton 1952, p. 329; Mitchell 2019, p. 165.

- ↑ Broughton 1952, p. 342.

- 1 2 Mitchell 2019, p. 165.

- ↑ Funerary inscription of Lucius Munatius Plancus CIL X, 6087 LacusCurtius.

- ↑ Cic. Fam. 10, 17–18, 23.

- ↑ Mitchell 2019, p. 173, citing Cic. Fam. 10.6.

- ↑ Mitchell 2019, p. 173.

- ↑ Mitchell 2019, pp. 173–74.

- ↑ Mitchell 2019, pp. 174–75.

- ↑ Mitchell 2019, p. 175.

- ↑ Cadoux & Lintott 2012.

- ↑ Mitchell 2019, p. 176.

- ↑ Broughton 1952, p. 348.

- ↑ Broughton 1952, p. 357.

- ↑ Broughton 1952, p. 374.

- ↑ Broughton 1952, p. 382.

- ↑ Broughton 1952, pp. 388, 392.

- ↑ Broughton 1952, p. 408, noting however that Liv. Per. 131 indicates that Plancus was legate.

- ↑ Broughton 1952, pp. 408–9.

- ↑ Mitchell 2019, p. 179.

- 1 2 Mitchell 2019, p. 180.

- ↑ Johnson, John Robert (1978). "The authenticity and validity of Antony's will". L'Antiquité Classique. 47 (2): 494–503. doi:10.3406/antiq.1978.1908. ISSN 0770-2817. JSTOR 41651325.

Antony was 'proved' un-Roman... his will had (a) proclaimed the legitimacy of Caesarion, (b) had named his children by Cleopatra as heirs of legatees, and (c) had directed that his own body be buried beside that of his Oriental mistress...

- ↑ Mitchell 2019, p. 180, citing Suet. Aug. 7.2; Vell. Pat. 2.91; Dio 53.16.6–8.

- ↑ Mitchell 2019, p. 181 n. 60.

- ↑ Vell. Pat. 2.95.

- ↑ Suet. Ner. 4.

- ↑ Tacitus Annals, 1.39.

- ↑ Tacitus Annals, 2.43.4, 2.74.2, 3.8-18; Dio 57.18.9.

- ↑ Tacitus Annals, 2.55.5, 2.74.2.

- ↑ Tacitus Annals, 6.24.4; Dio 58.22.5.

- ↑ Dio 59.20.7.

- ↑ Tacitus Annals, 3.17-18.

- ↑ Mitchell 2019, p. 163.

- 1 2 Litwan, Peter (2014). "Stadtgründer, Stammvater, Patron oder doch nicht? : Basler Inschriften, Darstellungen und Texte aus fast einem halben Jahrtausend zu L. Munatius Plancus". Basler Zeitschrift für Geschichte und Altertumskunde. p. 241 – via E-Periodica.

- ↑ Mitchell 2019, p. 163, citing Cic. Fam. 10.3.3.

- ↑ Mitchell 2019.

- ↑ Mitchell 2019, p. 177, citing Vell. Pat. 2.83.1 (inter hunc apparatum belli Plancus, non iudicio recta legendi neque amore rei publicae aut Caesaris, quippe haec semper impugnabat, sed mordo proditor...).

- ↑ Mitchell 2019, p. 177.

- ↑ Mitchell 2019, pp. 177–78.

- ↑ Mitchell 2019, p. 163, citing Syme, Roman Revolution (1939), p. 165.

- ↑ Mitchell 2019, p. 164.

- Sources

- Broughton, Thomas Robert Shannon (1952). The magistrates of the Roman republic. Vol. 2. New York: American Philological Association.

- Crawford, Michael H (1974). Roman Republican coinage. London: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-07492-4. OCLC 1288923.

- Hornblower, Simon; et al., eds. (2012). The Oxford classical dictionary (4th ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-954556-8. OCLC 959667246.

- Cadoux, Theodore John; Lintott, Andrew. "triumviri". In OCD4 (2012).

- Richardson, Geoffrey Walter; Cadoux, Theodore John; Badian, Ernst. "Munatius Plancus, Lucius". In OCD4 (2012).

- Mitchell, Hannah (2019). "The reputation of L Munatius Plancus and the idea of "serving the times"". In Morrell, Kit; Osgood, Josiah; Kathryn, Welch (eds.). The alternative Augustan age. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 163–81. ISBN 978-0-19-090141-7. OCLC 1114973036.

- Zmeskal, Klaus (2009). Adfinitas (in German). Vol. 1. Passau.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)