| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /kləˈpɪdəɡrɛl, kloʊ-/[1] |

| Trade names | Plavix, Iscover, others[2] |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a601040 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | >50% |

| Protein binding | 94–98% |

| Metabolism | Liver |

| Onset of action | 2 hours[6] |

| Elimination half-life | 7–8 hours (inactive metabolite) |

| Duration of action | 5 days[6] |

| Excretion | 50% Kidney 46% bile duct |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| PDB ligand | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.127.841 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

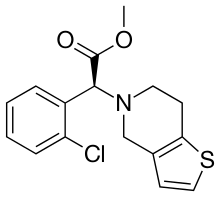

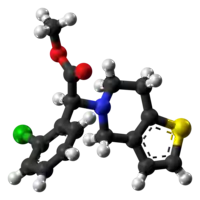

| Formula | C16H16ClNO2S |

| Molar mass | 321.82 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Clopidogrel—sold under the brand names Plavix and Deplat, among others[2]—is an antiplatelet medication used to reduce the risk of heart disease and stroke in those at high risk.[6] It is also used together with aspirin in heart attacks and following the placement of a coronary artery stent (dual antiplatelet therapy).[6] It is taken by mouth.[6] Its effect starts about two hours after intake and lasts for five days.[6]

Common side effects include headache, nausea, easy bruising, itching, and heartburn.[6] More severe side effects include bleeding and thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura.[6] While there is no evidence of harm from use during pregnancy, such use has not been well studied.[3] Clopidogrel is in the thienopyridine-class of antiplatelets.[6] It works by irreversibly inhibiting a receptor called P2Y12 on platelets.[6]

Clopidogrel was patented in 1982, and approved for medical use in 1997.[5][7] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[8] In 2020, it was the 29th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 19 million prescriptions.[9][10] It is available as a generic medication.[6]

Medical uses

Clopidogrel is used to prevent heart attack and stroke in people who are at high risk of these events, including those with a history of myocardial infarction and other forms of acute coronary syndrome, stroke, and those with peripheral artery disease.

Treatment with clopidogrel or a related drug is recommended by the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology for people who:

- Present for treatment with a myocardial infarction with ST-elevation[11] including

- A loading dose given in advance of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), followed by a full year of treatment for those receiving a vascular stent

- A loading dose given in advance of fibrinolytic therapy, continued for at least 14 days

- Present for treatment of a non-ST elevation myocardial infarction or unstable angina[12]

- Including a loading dose and maintenance therapy in those receiving PCI and unable to tolerate aspirin therapy

- Maintenance therapy for up to 12 months in those at medium to high risk for which a noninvasive treatment strategy is chosen

- In those with stable ischemic heart disease, treatment with clopidogrel is described as a "reasonable" option for monotherapy in those who cannot tolerate aspirin, as is treatment with clopidogrel in combination with aspirin in certain high risk patients.[13]

It is also used, along with acetylsalicylic acid (ASA, aspirin), for the prevention of thrombosis after placement of a coronary stent[14] or as an alternative antiplatelet drug for people intolerant to aspirin.[15] It is available as a fixed-dose combination.[16]

A meta-analysis found clopidogrel's benefit as an antiplatelet drug in reducing cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, and stroke to be 25% benefit in smokers, with little (8%) benefit in non-smokers.[17]

Consensus-based therapeutic guidelines also recommend the use of clopidogrel rather than aspirin (ASA) for antiplatelet therapy in people with a history of gastric ulceration, as inhibition of the synthesis of prostaglandins by ASA can exacerbate this condition. In people with healed ASA-induced ulcers, however, those receiving ASA plus the proton-pump inhibitor (PPI) esomeprazole had a lower incidence of recurrent ulcer bleeding than those receiving clopidogrel.[18] However, prophylaxis with proton-pump inhibitors along with clopidogrel following acute coronary syndrome may increase adverse cardiac outcomes, possibly due to inhibition of CYP2C19, which is required for the conversion of clopidogrel to its active form.[19][20][21] The European Medicines Agency has issued a public statement on a possible interaction between clopidogrel and proton-pump inhibitors.[22] However, several cardiologists have voiced concern that the studies on which these warnings are based have many limitations and that it is not certain whether an interaction between clopidogrel and proton-pump inhibitors is real.[23]

Adverse effects

Serious adverse drug reactions associated with clopidogrel therapy include:

- Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (incidence: four per million patients treated)[24][5]

- Hemorrhage – the annual incidence of hemorrhage may be increased by the coadministration of aspirin.[25]

In the CURE trial, people with acute coronary syndrome without ST elevation were treated with aspirin plus either clopidogrel or placebo and followed for up to one year. The following rates of major bleed were seen:[5]

- Any major bleeding: clopidogrel 3.7%, placebo 2.7%

- Life-threatening bleeding: clopidogrel 2.2%, placebo 1.8%

- Hemorrhagic stroke: clopidogrel 0.1%, placebo 0.1%

The CAPRIE trial compared clopidogrel monotherapy to aspirin monotherapy for 1.6 years in people who had recently experienced a stroke or heart attack. In this trial the following rates of bleeding were observed.[5]

- Gastrointestinal hemorrhage: clopidogrel 2.0%, aspirin 2.7%

- Intracranial bleeding: clopidogrel 0.4%, aspirin 0.5%

In CAPRIE, itching was the only adverse effect seen more frequently with clopidogrel than aspirin. In CURE, there was no difference in the rate of non-bleeding adverse events.[5]

Rashes and itching were uncommon in studies (between 0.1 and 1% of people); serious hypersensitivity reactions are rare.[26]

Interactions

Clopidogrel generally has a low potential to interact with other pharmaceutical drugs. Combination with other drugs that affect blood clotting, such as aspirin, heparins and thrombolytics, showed no relevant interactions. Naproxen did increase the likelihood of occult gastrointestinal bleeding, as might be the case with other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. As clopidogrel is metabolized by the liver enzyme CYP2C19, in cellular models it has been theorized that it might increase blood plasma levels of other drugs that are metabolized by this enzyme, such as phenytoin and tolbutamide. Clinical studies showed that this mechanism is irrelevant for practical purposes.[26]

In November 2009, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) announced that clopidogrel should be used with caution in people using the proton-pump inhibitors omeprazole or esomeprazole,[27][28][29] but pantoprazole appears to be safe.[30] The newer antiplatelet agent prasugrel has minimal interaction with (es)omeprazole, hence might be a better antiplatelet agent (if no other contraindications are present) in people who are on these proton-pump inhibitors.[31]

Pharmacology

Clopidogrel is a prodrug which is metabolized by the liver into its active form. The active form specifically and irreversibly inhibits the P2Y12 subtype of ADP receptor, which is important in activation of platelets and eventual cross-linking by the protein fibrin.[32]

Pharmacokinetics and metabolism

After repeated oral doses of 75 mg of clopidogrel (base), plasma concentrations of the parent compound, which has no platelet-inhibiting effect, are very low and, in general, are below the quantification limit (0.258 µg/L) beyond two hours after dosing.

Clopidogrel is a prodrug, which is activated in two steps, first by the enzymes CYP2C19, CYP1A2 and CYP2B6, then by CYP2C19, CYP2C9, CYP2B6 and CYP3A.[32] Due to opening of the thiophene ring, the chemical structure of the active metabolite has three sites that are stereochemically relevant, making a total of eight possible isomers. These are: a stereocentre at C4 (attached to the —SH thiol group), a double bond at C3—C16, and the original stereocentre at C7. Only one of the eight structures is an active antiplatelet drug. This has the following configuration: Z configuration at the C3—C16 double bond, the original S configuration at C7,[33] and, although the stereocentre at C4 cannot be directly determined, as the thiol group is too reactive, work with the active metabolite of the related drug prasugrel suggests the R-configuration of the C4 group is critical for P2Y12 and platelet-inhibitory activity.

The active metabolite has an elimination half-life of about 0.5 to 1.0 h, and acts by forming a disulfide bridge with the platelet ADP receptor. Patients with a variant allele of CYP2C19 are 1.5 to 3.5 times more likely to die or have complications than patients with the high-functioning allele.[34][35][36]

Following an oral dose of 14C-labeled clopidogrel in humans, about 50% was excreted in the urine and 46% in the feces in the five days after dosing.[6]

- Effect of food: Administration of clopidogrel bisulfate with meals did not significantly modify the bioavailability of clopidogrel as assessed by the pharmacokinetics of the main circulating metabolite.

- Absorption and distribution: Clopidogrel is rapidly absorbed after oral administration of repeated doses of 75-milligram clopidogrel (base), with peak plasma levels (about 3 mg/L) of the main circulating metabolite occurring around one hour after dosing. The pharmacokinetics of the main circulating metabolite are linear (plasma concentrations increased in proportion to dose) in the dose range of 50 to 150 mg of clopidogrel. Absorption is at least 50% based on urinary excretion of clopidogrel-related metabolites.

Clopidogrel and the main circulating metabolite bind reversibly in vitro to human plasma proteins (98% and 94%, respectively). The binding is not saturable in vitro up to a concentration of 110 μg/mL.

- Metabolism and elimination: In vitro and in vivo, clopidogrel undergoes rapid hydrolysis into its carboxylic acid derivative. In plasma and urine, the glucuronide of the carboxylic acid derivative is also observed.

In 2010 the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) added a boxed warning, later updated, to Plavix, alerting that the drug can be less effective in people unable to metabolize the drug to convert it to its active form.[37]

Pharmacogenetics

CYP2C19 is an important drug-metabolizing enzyme that catalyzes the biotransformation of many clinically useful drugs, including antidepressants, barbiturates, proton-pump inhibitors, and antimalarial and antitumor drugs. Clopidogrel is one of the drugs metabolized by this enzyme.[6]

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) put a black box warning on Plavix in 2010, later updated, to make patients and healthcare providers aware that CYP2C19-poor metabolizers, representing up to 14% of patients, are at high risk of treatment failure and that testing is available.[37] Patients with variants in cytochrome P-450 2C19 (CYP2C19) have lower levels of the active metabolite of clopidogrel, less inhibition of platelets, and a 3.58-times greater risk for major adverse cardiovascular events such as death, heart attack, and stroke; the risk was greatest in CYP2C19 poor metabolizers.[5][38]

A published review showed that some mutations of CYP2C19, CYP3A4, CYP2C9, CYP2B6, and CYP1A2 genes could affect the clinical efficacy and safety of clopidogrel treatment. For instance, patients carrying the mutations CYP2C19*2, CYP2C19*3, CYP2C9*2, CYP2C9*3, and CYP2B6*5 alleles may not respond to clopidogrel due to poor platelet inhibition efficacy revealed among them.[39]

Mechanism of action

The active metabolite of clopidogrel specifically and irreversibly inhibits the P2Y12 subtype of ADP receptor, which is important in activation of platelets and eventual cross-linking by the protein fibrin.[32] Platelet inhibition can be demonstrated two hours after a single dose of oral clopidogrel, but the onset of action is slow, so a loading dose of either 600 or 300 mg is administered when a rapid effect is needed.[40]

Society and culture

Economics

Plavix is marketed worldwide in nearly 110 countries, with sales of US$6.6 billion in 2009.[41] It was the second-top-selling drug in the world in 2007[42] and was still growing by over 20% in 2007. U.S. sales were US$3.8 billion in 2008.[43]

Before the expiry of its patent, clopidogrel was the second best-selling drug in the world. In 2010, it grossed over US$9 billion in global sales.[44]

In 2006, generic clopidogrel was briefly marketed by Apotex, a Canadian generic pharmaceutical company before a court order halted further production until resolution of a patent infringement case brought by Bristol-Myers Squibb.[45] The court ruled that Bristol-Myers Squibb's patent was valid and provided protection until November 2011.[46] The FDA extended the patent protection of clopidogrel by six months, giving exclusivity that would expire on 17 May 2012.[47] The FDA approved generic versions of Plavix on 17 May 2012.[48]

Names

Generic clopidogrel is marketed by many companies worldwide under many brand names.[2]

List of brand names |

|---|

|

As of March 2017, brands included Aclop, Actaclo, Agregex, Agrelan, Agrelax, Agreless, Agrelex, Agreplat, Anclog, Angiclod, Anplat, Antiagrex, Antiban, Antigrel, Antiplaq, Antiplar, Aplate, Apolets, Areplex, Artepid, Asogrel, Atelit, Atelit, Ateplax, Atervix, Atheros, Athorel, Atrombin, Attera, Bidogrel, Bigrel, Borgavix, Carder, Cardogrel, Carpigrel, Ceraenade, Ceruvin, Cidorix, Clatex, Clavix, Clentel, Clentel, Clidorel, Clodel, Clodelib, Clodian, Clodil, Cloflow, Clofre, Clogan, Clogin, Clognil, Clogrel, Clogrelhexal, Clolyse, Clont, Clood, Clopacin, Clopcare, Clopeno, Clopex Agrel, Clopez, Clopi, Clopid, Clopida, Clopidep, Clopidexcel, Clopidix, Clopidogrel, Clopidogrelum, Clopidomed, Clopidorex, Clopidosyn, Clopidoteg, Clopidowel, Clopidra, Clopidrax, Clopidrol, Clopigal, Clopigamma, Clopigrel, Clopilet, Clopimed, Clopimef, Clopimet, Clopinovo, Clopione, Clopiright, Clopirite, Clopirod, Clopisan, Clopistad, Clopistad, Clopitab, Clopithan, Clopitro, ClopiVale, Clopivas, Clopivaz, Clopivid, Clopivin, Clopix, Cloplat, Clopra, Cloprez, Cloprez, Clopval, Clorel, Cloriocard, Cloroden, Clotix, Clotiz, Clotrombix, Clova, Clovas, Clovax, Clovelen, Clovex, Clovexil, Clovix, Clovvix, Copalex, Copegrel, Copidrel, Copil, Cordiax, Cordix, Corplet, Cotol, CPG, Cugrel, Curovix, Dapixol, Darxa, Dasogrel-S, Dclot, Defrozyp, Degregan, Deplat, Deplatt, Diclop, Diloxol, Dilutix, Diporel, Doglix, Dogrel, Dogrel, Dopivix, Dorel, Dorell, Duopidogrel, DuoPlavin, Eago, Egitromb, Espelio, Eurogrel, Expansia, Farcet, Flucogrel, Fluxx, Freeclo, Globel, Glopenel, Grelet, Greligen, Grelix, Grepid, Grepid, Grindokline, Heart-Free, Hemaflow, Hyvix, Idiavix, Insigrel, Iscover, Iskimil, Kafidogran, Kaldera, Kardogrel, Karum, Kerberan, Keriten, Klepisal, Klogrel, Klopide, Klopidex, Klopidogrel, Klopik, Klopis, Kogrel, Krossiler, Larvin, Lodigrel, Lodovax, Lofradyk, Lopigalel, Lopirel, Lyvelsa, Maboclop, Medigrel, Miflexin, Mistro, Mogrel, Monel, Monogrel, Moytor, Myogrel, Nabratin, Nadenel, Nefazan, Niaclop, Nivenol, Noclog, Nofardom, Nogreg, Nogrel, Noklot, Norplat, Novigrel, Oddoral, Odrel, Olfovel, Opirel, Optigrel, Panagrel, Pedovex, Pegorel, Piax, Piclokare, Pidgrel, Pidogrel, Pidogul, Pidovix, Pigrel, Pingel, Placta, Pladel, Pladex, Pladogrel, Plagerine, Plagrel, Plagril, Plagrin, Plahasan, Plamed, Planor, PlaquEx, Plasiver, Plataca, Platarex, Platec, Platel, Platelex, Platexan, Platil, Platless, Platogrix, Platrel, Plavedamol, Plavicard, Plavictonal, Plavidosa, Plavigrel, Plavihex, Plavitor, Plavix, Plavocorin, Plavogrel, Plavos, Pleyar, Plogrel, Plvix, Pravidel, Pregrel, Provic, Psygrel, Q.O.L, Ravalgen, Replet, Respekt, Revlis, Ridlor, Roclas, Rozak, Sanvix, Sarix, Sarovex, Satoxi, Shinclop, Sigmagrel, Simclovix, Sintiplex, Stazex, Stroka, Stromix, Sudroc, Synetra, Talcom, Tansix, Tessyron, Thinrin, Throimper, Thrombifree, Thrombo, Timiflo, Tingreks, Torpido, Triosal, Trogran, Troken, Trombex, Trombix, Tuxedon, Unigrel, Unplaque, Vaclo, Vasocor, Vatoud, Venicil, Vidogrel, Vivelon, Vixam, Xydrel, Zakogrel, Zillt, Zopya, Zylagren, Zyllt, and Zystol.[2] As of 2017, it was marketed as a combination drug with acetylsalicylic acid (aspirin) under the brand names Anclog Plus, Antiban-ASP, Asclop, Asogrel-A, Aspin-Plus, Cargrel-A, Clas, Clasprin, Clavixin Duo, Clodrel Forte, Clodrel Plus, Clofre AS, Clognil Plus, Clontas, Clopid-AS, Clopid-AS, Clopida A, Clopil-A, Clopirad-A, Clopirin, Clopitab-A, Clorel-A, Clouds, Combiplat, Coplavix, Coplavix, Cugrel-A, Dorel Plus, DuoCover, DuoCover, DuoPlavin, DuoPlavin, Ecosprin Plus, Grelet-A, Lopirel Plus, Myogrel-AP, Noclog Plus, Noklot Plus, Norplat-S, Odrel Plus, Pidogul A, Pladex-A, Plagerine-A, Plagrin Plus, Plavix Plus, Replet Plus, Stromix-A, and Thrombosprin.[2] |

Veterinary uses

Clopidogrel has been shown to be effective at decreasing platelet aggregation in cats, so its use in prevention of feline aortic thromboembolism has been advocated.[49]

References

- ↑ "Clopidogrel". Lexico Dictionaries. Archived from the original on 25 October 2019. Retrieved 26 October 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Clopidogrel International brand names". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 1 April 2017. Retrieved 1 April 2017.

- 1 2 "Clopidogrel (Plavix) Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 21 December 2016. Retrieved 14 December 2016.

- ↑ "FDA-sourced list of all drugs with black box warnings (Use Download Full Results and View Query links.)". nctr-crs.fda.gov. FDA. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Plavix- clopidogrel bisulfate tablet, film coated". DailyMed. Bristol-Myers Squibb/Sanofi Pharmaceuticals Partnership. 17 May 2019. Archived from the original on 4 August 2020. Retrieved 26 December 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 "Clopidogrel Bisulfate". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 21 December 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ↑ Fischer J, Ganellin CR (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 453. ISBN 9783527607495. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016.

- ↑ World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ↑ "The Top 300 of 2020". ClinCalc. Retrieved 7 October 2022.

- ↑ "Clopidogrel - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Retrieved 7 October 2022.

- ↑ O'Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD, et al. (January 2013). "2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines". J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 61 (4): e78–140. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2012.11.019. PMID 23256914.

- ↑ Jneid H, Anderson JL, Wright RS, et al. (August 2012). "2012 ACCF/AHA focused update of the guideline for the management of patients with unstable angina/Non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (updating the 2007 guideline and replacing the 2011 focused update): a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines". Circulation. 126 (7): 875–910. doi:10.1161/CIR.0b013e318256f1e0. PMID 22800849.

- ↑ Fihn SD, Gardin JM, Abrams J, et al. (December 2012). "2012 ACCF/AHA/ACP/AATS/PCNA/SCAI/STS guideline for the diagnosis and management of patients with stable ischemic heart disease: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines, and the American College of Physicians, American Association for Thoracic Surgery, Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons". Circulation. 126 (25): 3097–137. doi:10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182776f83. PMID 23166210.

- ↑ Rossi S, editor. Australian Medicines Handbook 2006. Adelaide: Australian Medicines Handbook; 2006. ISBN 0-9757919-2-3

- ↑ Michael D Randall; Karen E Neil (2004). Disease management. 2nd ed. London: Pharmaceutical Press. 159.

- ↑ "DuoPlavin EPAR". European Medicines Agency (EMA). 17 September 2018. Archived from the original on 4 September 2020. Retrieved 21 August 2020.

- ↑ Gagne JJ, Bykov K, Choudhry NK, et al. (17 September 2013). "Effect of smoking on comparative efficacy of antiplatelet agents: systematic review, meta-analysis, and indirect comparison". BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 347: f5307. doi:10.1136/bmj.f5307. PMC 3775704. PMID 24046285.

- ↑ Chan FK, Ching JY, Hung LC, et al. (2005). "Clopidogrel versus aspirin and esomeprazole to prevent recurrent ulcer bleeding". N. Engl. J. Med. 352 (3): 238–44. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa042087. PMID 15659723.

- ↑ Mistry SD, Trivedi HR, Parmar DM, et al. (2011). "Impact of proton pump inhibitors on efficacy of clopidogrel: Review of evidence". Indian Journal of Pharmacology. 43 (2): 183–6. doi:10.4103/0253-7613.77360. PMC 3081459. PMID 21572655.

- ↑ Ho PM, Maddox TM, Wang L, et al. (2009). "Risk of adverse outcomes associated with concomitant use of clopidogrel and proton pump inhibitors following acute coronary syndrome". Journal of the American Medical Association. 301 (9): 937–44. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.261. PMID 19258584.

- ↑ Stockl KM, Le L, Zakharyan A, et al. (April 2010). "Risk of rehospitalization for patients using clopidogrel with a proton pump inhibitor" (PDF). Arch Intern Med. 170 (8): 704–10. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2010.34. ISSN 1538-3679. PMID 20421557. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016.

- ↑ Wathion N. "Public statement on possible interaction between clopidogrel and proton pump inhibitors" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 February 2011. Retrieved 31 March 2011.

- ↑ Hughes S. "EMEA issues warning on possible clopidogrel-PPI interaction, but is there really a problem?". Archived from the original on 22 May 2013. Retrieved 31 March 2011.

- ↑ Zakarija A, Bandarenko N, Pandey DK, et al. (2004). "Clopidogrel-Associated TTP An Update of Pharmacovigilance Efforts Conducted by Independent Researchers, Pharmaceutical Suppliers, and the Food and Drug Administration". Stroke. 35 (2): 533–8. doi:10.1161/01.STR.0000109253.66918.5E. PMID 14707231.

- ↑ Diener HC, Bogousslavsky J, Brass LM, et al. (2004). "Aspirin and clopidogrel compared with clopidogrel alone after recent ischaemic stroke or transient ischaemic attack in high-risk patients (MATCH): randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial". The Lancet. 364 (9431): 331–7. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16721-4. PMID 15276392. S2CID 9874277.

- 1 2 Jasek, W, ed. (2007). Austria-Codex (in German) (62nd ed.). Vienna: Österreichischer Apothekerverlag. pp. 6526–7. ISBN 978-3-85200-181-4.

- ↑ DeNoon DJ (23 February 2016). "FDA Warns Plavix Patients of Drug Interactions". WebMD. Archived from the original on 23 February 2016. Retrieved 23 November 2009.

- ↑ "Public Health Advisory: Updated Safety Information about a drug interaction between Clopidogrel Bisulfate (marketed as Plavix) and Omeprazole (marketed as Prilosec and Prilosec OTC)". Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 17 November 2009. Archived from the original on 29 December 2009. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- ↑ Farhat N, Haddad N, Crispo J, et al. (February 2019). "Trends in concomitant clopidogrel and proton pump inhibitor treatment among ACS inpatients, 2000-2016". Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 75 (2): 227–235. doi:10.1007/s00228-018-2564-8. PMID 30324301. S2CID 53085923.

- ↑ Wedemeyer RS, Blume H (2014). "Pharmacokinetic Drug Interaction Profiles of Proton Pump Inhibitors: An Update". Drug Safety. 37 (4): 201–11. doi:10.1007/s40264-014-0144-0. PMC 3975086. PMID 24550106.

- ↑ John J, Koshy SK (2012). "Current Oral Antiplatelets: Focus Update on Prasugrel". The Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine. 25 (3): 343–349. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2012.03.100270. PMID 22570398.

- 1 2 3 Cattaneo M (March 2012). "Response variability to clopidogrel: is tailored treatment, based on laboratory testing, the right solution?". Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 10 (3): 327–36. doi:10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04602.x. PMID 22221409. S2CID 34477003.

- 1 2 Pereillo JM, Maftouh M, Andrieu A, et al. (2002). "Structure and stereochemistry of the active metabolite of clopidogrel". Drug Metab. Dispos. 30 (11): 1288–95. doi:10.1124/dmd.30.11.1288. PMID 12386137. S2CID 2493588.

- ↑ Mega JL, Close SL, Wiviott SD, et al. (January 2009). "Cytochrome p-450 polymorphisms and response to clopidogrel". The New England Journal of Medicine. 360 (4): 354–62. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0809171. PMID 19106084.

- ↑ Simon T, Verstuyft C, Mary-Krause M, et al. (January 2009). "Genetic Determinants of Response to Clopidogrel and Cardiovascular Events". The New England Journal of Medicine. 360 (4): 363–75. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0808227. PMID 19106083.

- ↑ Collet JP, Hulot JS, Pena A, et al. (January 2009). "Cytochrome P450 2C19 polymorphism in young patients treated with clopidogrel after myocardial infarction: a cohort study". The Lancet. 373 (9660): 309–17. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61845-0. PMID 19108880. S2CID 22405890.

- 1 2 "Safety announcement: Reduced effectiveness of Plavix in patients who are poor metabolizers". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 3 August 2017. Archived from the original on 15 March 2010.

- ↑ "FDA Drug Safety Communication: Reduced effectiveness of Plavix (clopidogrel) in patients who are poor metabolizers of the drug". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 28 June 2019. Archived from the original on 18 June 2019. Retrieved 30 January 2022.

- ↑ Alkattan A, Alsalameen E (June 2021). "Polymorphisms of genes related to phase-I metabolic enzymes affecting the clinical efficacy and safety of clopidogrel treatment". Expert Opinion on Drug Metabolism & Toxicology. 17 (6): 685–95. doi:10.1080/17425255.2021.1925249. PMID 33931001. S2CID 233470717.

- ↑ Clopidogrel Multum Consumer Information

- ↑ "New products and markets fuel growth in 2005". IMS Health. Archived from the original on 3 June 2008. Retrieved 2 March 2009.

- ↑ "Top Ten Global Products – 2007" (PDF). IMS Health. 26 February 2008. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 February 2011. Retrieved 2 March 2009.

- ↑ "Details for Plavix". Archived from the original on 14 August 2014.

- ↑ Topol EJ, Schork NJ (January 2011). "Catapulting clopidogrel pharmacogenomics forward". Nature Medicine. 17 (1): 40–41. doi:10.1038/nm0111-40. PMID 21217678. S2CID 32083067.

- ↑ "Preliminary Injunction Against Apotex Upheld on Appeal" (Press release). Bristol-Myers Squibb. 8 December 2006. Archived from the original on 14 April 2014. Retrieved 14 March 2010.

- ↑ "U.S. judge upholds Bristol, Sanofi patent on Plavix". Reuters. 19 June 2007. Archived from the original on 20 May 2011. Retrieved 5 September 2007.

- ↑ "FDA Gives Plavix a 6 Month Extension-Patent Now Expires on 17 May 2012". 26 January 2011. Archived from the original on 12 October 2011. Retrieved 12 January 2012.

- ↑ "FDA approves generic versions of blood thinner Plavix" (Press release). Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 17 May 2012. Archived from the original on 11 March 2016.

- ↑ Hogan DF, Andrews DA, Green HW, et al. (2004). "Antiplatelet effects and pharmacodynamics of clopidogrel in cats". J Am Vet Med Assoc. 225 (9): 1406–1411. doi:10.2460/javma.2004.225.1406. PMID 15552317.

Further reading

- Dean L (2012). "Clopidogrel Therapy and CYP2C19 Genotype". In Pratt VM, McLeod HL, Rubinstein WS, et al. (eds.). Medical Genetics Summaries. National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). PMID 28520346. Bookshelf ID: NBK84114.

External links

- "Clopidogrel". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- US Patent US4847265A for "Dextro-rotatory enantiomer of methyl alpha-5 (4,5,6,7-tetrahydro (3,2-c) thieno pyridyl) (2-chlorophenyl)-acetate and the pharmaceutical compositions containing it"