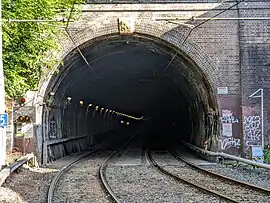

The tunnel between Glebe and Jubilee Park, now used by the Inner West Light Rail | |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Location | Metropolitan Goods railway line, Pyrmont, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia |

| Coordinates | 33°52′37″S 151°11′11″E / 33.8770°S 151.1864°E |

| Operation | |

| Opened | 1922 |

| Owner | Transport Asset Holding Entity |

| Official name | Pyrmont and Glebe Railway Tunnels; Metro Light Rail |

| Type | State heritage (complex / group) |

| Designated | 2 April 1999 |

| Reference no. | 1225 |

| Type | Railway Tunnel |

| Category | Transport – Rail |

The Pyrmont and Glebe railway tunnels are heritage-listed railway tunnels, once part of the Metropolitan Goods railway line, Pyrmont and Glebe, New South Wales, Australia. The tunnels now carry the Inner West Light Rail line. The property is owned by Transport Asset Holding Entity, a state government agency. The tunnels were added to the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 2 April 1999.[1]

History

Background

The Leichhardt area, including Glebe, was originally inhabited by the Wangal clan of Aboriginal people. After 1788 diseases such as smallpox and the loss of their hunting grounds caused huge reductions in their numbers and they moved further inland. Since European settlement the foreshores of Blackwattle Bay and Rozelle Bay have developed a unique maritime, industrial and residential character – a character which continues to evolve as areas which were originally residential estates, then industrial areas, are redeveloped for residential units and parklands.[1]

The first formal grant in the Glebe area was a 162 hectares (400 acres) grant to Rev. Richard Johnson, the colony's first chaplain, in 1789. The Glebe (land allocated for the maintenance of a church minister) comprised rolling shale hills covering sandstone, with several sandstone cliff faces. The ridges were drained by several creeks including Blackwattle Creek, Orphan School Creek and Johnston Creek. Extensive swampland surrounded the creeks. On the shale ridges, heavily timbered woodlands contained several varieties of eucalypts while the swamplands and tidal mudflats had mangroves, swamp oaks (Casuarina glauca) and black wattles (Callicoma serratifolia) after which the bay is named. Blackwattle Swamp was first mentioned by surveyors in the 1790s and Blackwattle Swamp Bay in 1807. By 1840 it was called Blackwattle Bay. Boat parties collected wattles and reeds for the building of huts, and kangaroos and emus were hunted by the early settlers who called the area the Kangaroo Ground. Rozelle Bay is thought to have been named after a schooner which once moored in its waters.[1]

Johnson's land remained largely undeveloped until 1828, when the Church and School Corporation subdivided it into 28 lots, three of which they retained for church use.[2][1]

The Church sold 27 allotments in 1828 – north on the point and south around Broadway. The Church kept the middle section where the Glebe Estate is now. On the point the sea breezes attracted the wealthy who built villas. The Broadway end attracted slaughterhouses and boiling down works that used the creek draining to Blackwattle Swamp.[1] Up until the 1970s the Glebe Estate was in the possession of the Church.[1]

On the point the sea breezes attracted the wealthy who built villas. The Broadway end attracted slaughterhouses and boiling down works that used the creek draining to Blackwattle Swamp. Smaller working-class houses were built around these industries. Abattoirs were built there from the 1860s.[1] When Glebe was made a municipality in 1859 there were pro and anti-municipal clashes in the streets. From 1850 Glebe was dominated by wealthier interests.[1]

Reclaiming the swamp, Wentworth Park opened in 1882 as a cricket ground and lawn bowls club. Rugby union football was played there in the late 19th century. The dog racing started in 1932. In the early 20th century modest villas were broken up into boarding houses as they were elsewhere in the inner city areas. The wealthier moved into the suburbs which were opening up through the railways. Up until the 1950s Sydney was the location for working class employment – it was a port and industrial city. By the 1960s central Sydney was becoming a corporate city with service-based industries – capital intensive not labour intensive. A shift in demographics occurred, with younger professionals and technical and administrative people servicing the corporate city wanting to live close by. Housing was coming under threat and the heritage conservation movement was starting. The fish markets moved in in the 1970s. An influx of students came to Glebe in the 1960s and 1970s.[3][1]

Description

The heritage-listed structures include a double-lined tunnel, completed in 1922 and cuttings and track formation.[1]

Pyrmont railway cuttings and tunnel

The railway cutting through Pyrmont is a two-track-wide, straight-sided excavation through the ridge of the peninsula from the commencement of Jones Bay Road, where the line deviated from the wharf sidings (now removed), through the current location of the John Street Square light rail station. Approaching the station, the line passes through a short tunnel under Harris Street. After the station it enters a main tunnel near John Street opposite Mount Street. These tunnels are bored through the escarpment and are brick-lined. The tunnel exits near Jones Street at Saunders Lane and the line continues in a cutting which progressively opens out on the western side before falling ground levels bring the line on to a brick viaduct near where Jones and Allen Streets intersected before the railway was built. This heritage-listed viaduct continues across Wentworth Park towards Glebe. The railway cutting is through Pyrmont sandstone.[4]

Glebe railway tunnel

The Glebe railway tunnel runs approximately 800 metres (2,600 ft) from Lower Avon Street, Glebe (adjacent to the metro light rail Glebe stop) to Jubilee Park. Tunnel openings at the east and west end are built of brick in an English bond pattern, with the arch formed by bricks laid in soldier course, and featuring a sandstone keystone. The tunnel supports a double track currently used by the metro light rail system. The tunnel is approximately 8.3 metres (27 ft) wide and 5.9 metres (19 ft) high.[5]

Heritage listing

The brick tunnel and cuttings are a major feature of the landscape and layout of the Pyrmont area. They are important relics of the inner city freight system that operated to the wharves, including Darling Harbour, and connected through to the southern suburbs. The tunnel and its portals are an important brick structure that reflects the industrial nature of the area. The tunnel is a fairly long double-track brick-lined structure opened in 1922. As the line has not been electrified the structure remains virtually intact.[1]

Pyrmont and Glebe Railway Tunnels was listed on the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 2 April 1999 having satisfied the following criteria:[1] "The place possesses uncommon, rare or endangered aspects of the cultural or natural history of New South Wales. This item is assessed as historically rare. This item is assessed as scientifically rare. This item is assessed as architecturally rare."[1]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 "Pyrmont and Glebe Railway Tunnels". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Department of Planning & Environment. H01225. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC-BY 4.0 licence.

Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC-BY 4.0 licence. - ↑ City Plan Heritage, 2005, quoting Max Solling & Peter Reynolds "Leichhardt: On the Margins of the City", 1997, 14

- ↑ Murray, Dr Lisa (5 August 2009). "empty". Central Sydney.

- ↑ "Pyrmont Railway Cuttings, Tunnel & Weighbridge". New South Wales Heritage Database. Office of Environment & Heritage. Retrieved 25 October 2018.

- ↑ "Glebe Railway Tunnel". New South Wales Heritage Database. Office of Environment & Heritage. Retrieved 25 October 2018.

Attribution

![]() This Wikipedia article was originally based on Pyrmont and Glebe Railway Tunnels, entry number 1225 in the New South Wales State Heritage Register published by the State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) 2018 under CC-BY 4.0 licence, accessed on 13 October 2018.

This Wikipedia article was originally based on Pyrmont and Glebe Railway Tunnels, entry number 1225 in the New South Wales State Heritage Register published by the State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) 2018 under CC-BY 4.0 licence, accessed on 13 October 2018.

External links

- "Lost railways: Metropolitan goods line". Australia For Everyone. 2017.