| Boran | |

|---|---|

| Queen of Queens of Iran | |

The only known gold dinar of Boran (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston) | |

| Queen of the Sasanian Empire | |

| 1st Reign | 630 |

| Predecessor | Shahrbaraz |

| Successor | Shapur-i Shahrvaraz |

| 2nd Reign | June 631 – June 632 |

| Predecessor | Azarmidokht |

| Successor | Yazdegerd III |

| Died | June 632 Ctesiphon |

| Spouse | Kavad II |

| House | House of Sasan |

| Father | Khosrow II |

| Mother | Maria |

| Religion | Zoroastrianism |

Boran (also spelled Buran, Middle Persian: ![]() ) was Sasanian queen (banbishn) of Iran from 630 to 632, with an interruption of some months. She was the daughter of king (or shah) Khosrow II (r. 590–628) and the Byzantine princess Maria. She is the second of only three women to rule in Iranian history, the others being Musa of Parthia, and Boran's sister Azarmidokht.

) was Sasanian queen (banbishn) of Iran from 630 to 632, with an interruption of some months. She was the daughter of king (or shah) Khosrow II (r. 590–628) and the Byzantine princess Maria. She is the second of only three women to rule in Iranian history, the others being Musa of Parthia, and Boran's sister Azarmidokht.

In 628, her father was overthrown and executed by her brother-husband Kavad II, who also had all Boran's brothers and half-brothers executed, initiating a period of fractionalism within the empire. Kavad II died some months later, and was succeeded by his eight-year-old son Ardashir III, who after a rule of nigh two years, was killed and usurped by the Iranian military officer Shahrbaraz. Boran shortly ascended the throne with the aid of the military commander Farrukh Hormizd, who helped her to overthrow Shahrbaraz. She and her sister were the only legitimate heirs who could rule at the time. Boran inherited a declining empire that was engulfed in a civil war between two major factions, the Persian (Parsig) and Parthian (Pahlav) noble-families. She was committed to reviving the memory and prestige of her father, during whose reign the Sasanian Empire had grown to its largest territorial extent.

She was however not long afterwards replaced by Khosrow II's nephew Shapur-i Shahrvaraz, whose reign was even briefer than hers, being replaced by Azarmidokht, who was a Parsig nominee. She was in turn deposed soon afterwards and killed by the Pahlav under Farrukh Hormizd's son Rostam Farrokhzad, who restored Boran to the throne, thus making her queen for a second time. During her second reign, power was mostly in the hands of Rostam, which caused dissatisfaction among the Parsig and led to a revolt, during which Boran was killed by strangulation. She was succeeded by her nephew Yazdegerd III, the last Sasanian ruler, making her the penultimate ruler of the Sasanian Empire.

Albeit her two tenures of rule were shortlived, she did try to bring stability to Iran by the implementation of just laws, reconstruction of the infrastructure, and by lowering taxes and minting coins. Diplomatically, she desired good relations with her western neighbours–the Byzantines, whom she had an embassy sent to, which was well received by emperor Heraclius (r. 610–641).

Name

Boran's name appears as Bōrān (or Burān) on her coinage,[1] which is considered by the French historian Gignoux to be a hypocoristic from *baurāspa ('having many horses').[2] The medieval Persian poet Ferdowsi refers to her as Pūrāndokht in his epic poem, the Shahnameh ('The Book of Kings'). The suffix of dokht (-dukht in Middle Persian), meaning 'daughter', was a new development made in Middle Iranian languages to more easily differentiate a female's name from that of a male.[3][4] The suffix should not be taken too literally.[3] Her name appears as Boran (and similar) in the Chronicle of Khuzestan (7th-Century), Jacob of Edessa's Chronicle (8th-Century), in the Chronicle of Seert (9th-Century ?), in Agapius of Hierapolis's Kitab al-'Unwan (10th-Century) and in Michael the Syrian's Chronicle (12th-Century), as Βοράνη(ς) (Boránes) in Theophanes the Confessor's Chronicle (9th-Century), as Բորն (Born) in Tovma Artsruni's History of the House of Artsrunik (9th-Century), Baram in the Chronicle of 1234, George Kedrenos's Synopsis historion (11th-Century) and Bar Hebraeus's Chronicle (13th-Century),[5] Tūrān Dukht in the works of the 10th-century Persian historian Muhammad Bal'ami,[6] Queen Bor by the 7th-century Armenian historian Sebeos,[7] and Dukht-i Zabān by the 8th-century Arab historian Sayf ibn Umar.[8]

Background and early life

Boran was the daughter of the last prominent shah of Iran, Khosrow II (r. 590–628) and the Byzantine princess Maria.[2] Khosrow II was overthrown and executed in 628 by his own son Sheroe, better known by his dynastic name of Kavad II, who proceeded to have all Boran's brothers and half-brothers executed, including the heir Mardanshah.[9][10] This dealt a heavy blow to the empire, from which it would never recover. Boran and her sister Azarmidokht reportedly criticized and scolded Kavad II for his barbaric actions, which caused him to become remorseful.[11] According to Guidi's Chronicle, Boran was also Kavad II's wife, demonstrating the practice in Zoroastrianism of Khwedodah, or close-kin marriage.[12][2][lower-alpha 1]

The fall of Khosrow II culminated in the Sasanian civil war of 628–632, with the most powerful members of the nobility gaining full autonomy and starting to create their own government. The hostilities between the Persian (Parsig) and Parthian (Pahlav) noble-families were also resumed, which broke up the wealth of the nation.[15] A few months later, the devastating Plague of Sheroe swept through the western Sasanian provinces. Half the population, including Kavad II himself, perished.[15] He was succeeded by his eight-year-old son, who became Ardashir III. Ardashir's ascension was supported by both the Pahlav, Parsig, and a third major faction named the Nimruzi.[16] However, sometime in 629, the Nimruzi withdrew their support for the king, and started to conspire with the distinguished Iranian general Shahrbaraz to overthrow him.[17]

The Pahlav, under their leader Farrukh Hormizd of the Ispahbudhan clan, began supporting Boran as the new ruler of Iran, who subsequently started minting coins in the Pahlav areas of Amol, Nishapur, Gurgan and Ray.[17] On 27 April 630, Ardashir III was killed by Shahrbaraz,[18] who in turn was murdered, after a reign of forty days, in a coup by Farrukh Hormizd.[19] Farrukh Hormizd then helped Boran ascend the throne, sometime in late June 630.[20] Her accession was most likely due to her being the only remaining legitimate heir of the empire able to rule, along with Azarmidokht.[21][lower-alpha 2]

First reign

_(cropped).jpg.webp)

Boran was the first queen to rule the Sasanian Empire. However, it was not unusual for royal women to occupy political offices in the management of the country, and many such women before Boran had risen to prominence. A 5th-century Sasanian queen, Denag, had temporarily ruled as regent of the empire from its capital, Ctesiphon, during the dynastic struggle for the throne between her sons Hormizd III (r. 457–459) and Peroz I (r. 459–484) in 457–459.[22] The German classical scholar Josef Wiesehöfer also highlights the role of noblewomen in Sasanian Iran, stating that "Iranian records of the third century (inscriptions, reliefs, coins) show that the female members of the royal family received an unusual amount of attention and respect".[23] The story of the legendary Kayanian queen Humay Chehrzad and veneration towards the Iranian goddess Anahita probably also helped with the approval of Boran's rule.[24]

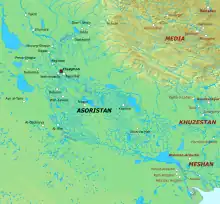

When Boran ascended the throne, she appointed Farrukh Hormizd as the chief minister (or wuzurg framadār) of the empire.[13] She then attempted to bring stability to Iran by the implementation of justice laws, reconstruction of the infrastructure, and by lowering taxes and minting coins.[12] Her rule was accepted by the nobility and clergy, which is apparent by her coin mints in the provinces of Pars, Khuzestan, Media, and Abarshahr.[12][25] No opposition was voiced towards her gender.[26] However, she was deposed in 630, and Shapur-i Shahrvaraz, the son of Shahrbaraz and a sister of Khosrow II, was made shah of Iran.[27] When he was not recognized by the Parsig faction of the powerful general Piruz Khosrow, he was deposed in favor of Azarmidokht, the sister of Boran.[28]

Second reign

Farrukh Hormizd, in order to strengthen his authority and create a harmonious modus vivendi between the Pahlav and Parsig families, asked Azarmidokht (who was a Parsig nominee) to marry him.[29] Not daring to refuse, she had him killed with the aid of the Mihranid aristocrat Siyavakhsh, who was the grandson of Bahram Chobin, the famous military commander (spahbed) and briefly shah of Iran.[30] Farrukh Hormizd's son Rostam Farrokhzad, who was at that time stationed in Khorasan, succeeded him as the leader of the Pahlav. In order to avenge his father, he left for Ctesiphon, in the words of the 9th century historian Sayf ibn Umar, "defeating every army of Azarmidokht that he met".[31] He then defeated Siyavakhsh's forces at Ctesiphon and captured the city.[31] Azarmidokht was shortly afterwards blinded and killed by Rostam, who restored Boran to the throne in June 631.[32][33] Boran complained to him about the state of the empire, which was at that time in a state of frailty and decline. She reportedly invited him to administer its affairs, and so allowed him to assume overall power.[31]

A settlement was reportedly made between the family of Boran and Rostam: according to Sayf, it stated that the queen should "entrust him [i.e., Rostam] with the rule for ten years,” at which point sovereignty would return "to the family of Sasan if they found any of their male offspring, and if not, then to their women".[31] Boran deemed the agreement appropriate, and had the factions of the country summoned (including the Parsig), where she declared Rostam as both the leader of the country and its military commander.[31] The Parsig faction agreed, with Piruz Khosrow being entrusted to administer the country alongside Rostam.[34]

The Parsig agreed to work with the Pahlav because of the fragility and decline of Iran, and also because their Mihranid collaborators had been temporarily defeated by Rostam.[34] However, the cooperation between the Parsig and Pahlav would prove short-lived, due to the unequal conditions between the two factions, with Rostam's faction having a much more significant portion of power under the approval of Boran.[34] Boran desired a good relationship with the Byzantine Empire, therefore she dispatched an embassy to its emperor Heraclius (r. 610–641), led by the catholicos Ishoyahb II and other dignitaries of the Iranian church.[13][21] Her embassy was amicably received by Heraclius.[35]

In the following year a revolt broke out in Ctesiphon. While the imperial army was occupied with other matters, the Parsig, dissatisfied with the regency of Rostam, called for the overthrow of Boran and the return of the prominent Parsig figure Bahman Jaduya, who had been dismissed by her.[36] Boran was killed shortly after; she was presumably strangled by Piruz Khosrow.[36][35] Hostilities were thus resumed between the two factions.[36] Not long afterwards, both Rostam and Piruz Khosrow were threatened by their own men, who had become alarmed by the declining state of the country.[37] Rostam and Piruz Khosrow thus agreed to work together once more, installing Boran's nephew Yazdegerd III (r. 632–651) on the throne, and so putting an end to the civil war.[37] According to the Muslim historian al-Tabari (died 923 AD), Boran reigned for a total of sixteen months.[35] The name of the Iranian appetizer Borani, may be derived from Boran.[38]

Coin mints and imperial ideology

During her reign, Boran's coinage was reverted to the design used by her father, due to her notions of the past and her personal respect for him.[39] Her minted coins included some that were more formal in design and were not intended for general use.[39] On her coins, it is declared that Boran was the restorer of her heritage, i.e., the race of gods. The translated inscription on her coins reads: "Boran, restorer of the race of Gods" (Middle Persian: Bōrān ī yazdān tōhm winārdār).[40] Her claim of being descended from the gods had not been used since the 4th-century, when it was used by the Sasanian shah Shapur II (r. 309–379).[41]

As with all Sasanian rulers, Boran's main denomination was the silver drachm (Middle Persian: drahm).[42] Between the reigns of Khosrow II and Yazdegerd III, Boran appears to have been the only ruler who minted bronze coins.[42] Only one gold issue of Boran is known, stored at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston.[42] The obverse of Boran's drachms and bronze issues depict her turned to the right, while on the reverse the Zoroastrian fire altar is depicted together with two attendants.[43] Boran's gold issue depicts her facing out instead of being in profile.[43]

On Boran's silver and bronze coins, double or triple row of pellets surround her portrait and astral signs of a crescent and a star are placed on the outer margin.[43] Boran is depicted wearing a round cap with three jewels or rosettes and a diadem; her bejewelled braids of hair fall from beneath the cap.[43] The diadem consists of two rows of pellets, presumably pearls, tied around Boran's forehead with segments visible.[43] The top her crown terminates in a pair of feathered wings, meant to represent the Zoroastrian divinity Verethragna, the hypostasis of 'victory'.[43] A crescent and globe is depicted between the feathered wings.[43] More astral signs are depicted at the top right (a star and crescent) and left of the crown (a single star).[43]

Notes

- ↑ According to the 7th-century Armenian historian Sebeos, Boran was the wife of Shahrbaraz. However, according to Chaumont and Pourshariati, this is unlikely.[13][14]

- ↑ The 9th-century historian Dinawari mentioned a son of Khosrow II and Gordiya, named Juvansher, as reigning before Boran. If true, it would mean that Juvansher managed to avoid Kavad II's slaughter of his brothers. This king remains obscure, and none of his coins have yet been found.[2]

References

- ↑ Daryaee 1999, pp. 78, 81.

- 1 2 3 4 Al-Tabari 1985–2007, v. 5: p. 404 (note 996).

- 1 2 Schmitt 2005a.

- ↑ Schmitt 2005b.

- ↑ Martindale, Jones & Morris 1992, p. 246.

- ↑ Pourshariati 2008, p. 183.

- ↑ Pourshariati 2008, p. 184.

- ↑ Pourshariati 2008, p. 203.

- ↑ Howard-Johnston 2010.

- ↑ Kia 2016, p. 284.

- ↑ Al-Tabari 1985–2007, v. 5: p. 399.

- 1 2 3 Daryaee 1999, p. 77.

- 1 2 3 Chaumont 1989, p. 366.

- ↑ Pourshariati 2008, p. 205 (note 1139).

- 1 2 Shahbazi 2005.

- ↑ Pourshariati 2008, pp. 178, 209.

- 1 2 Pourshariati 2008, p. 209.

- ↑ Pourshariati 2008, pp. 181, 209.

- ↑ Pourshariati 2008, pp. 182–3.

- ↑ Pourshariati 2008, pp. 185, 205.

- 1 2 Daryaee 2014, p. 36.

- ↑ Kia 2016, p. 248.

- ↑ Emrani 2009, p. 4.

- ↑ Emrani 2009, p. 5.

- ↑ Daryaee 2014, p. 59.

- ↑ Emrani 2009, p. 6.

- ↑ Pourshariati 2008, pp. 204–205.

- ↑ Pourshariati 2008, p. 204.

- ↑ Pourshariati 2008, pp. 205–206.

- ↑ Pourshariati 2008, pp. 206, 210.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Pourshariati 2008, p. 210.

- ↑ Pourshariati 2008, pp. 209–210.

- ↑ Gignoux 1987, p. 190.

- 1 2 3 Pourshariati 2008, p. 211.

- 1 2 3 Daryaee 2018, p. 258.

- 1 2 3 Pourshariati 2008, p. 218.

- 1 2 Pourshariati 2008, p. 219.

- ↑ Ghanoonparvar 1989, pp. 554–555.

- 1 2 Daryaee 2014, p. 35.

- ↑ Daryaee 2014, pp. 35–36.

- ↑ Daryaee 2009.

- 1 2 3 Malek & Curtis 1998, p. 116.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Malek & Curtis 1998, p. 117.

Sources

- Al-Tabari, Abu Ja'far Muhammad ibn Jarir (1985–2007). Ehsan Yar-Shater (ed.). The History of Al-Ṭabarī. Vol. V. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-4355-2.

- Chaumont, Marie Louise (1989). "Bōrān". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. IV, Fasc. 4. p. 366.

- Daryaee, Touraj (1999). "The Coinage of Queen Bōrān and Its Significance for Late Sāsānian Imperial Ideology". Bulletin (British Society for Middle Eastern Studies). 13: 77–82. JSTOR 24048959. (registration required)

- Daryaee, Touraj (2009). "Šāpur II". Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- Daryaee, Touraj (2014). Sasanian Persia: The Rise and Fall of an Empire. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-0-85771-666-8.

- Daryaee, Touraj (2018). "Boran". In Nicholson, Oliver (ed.). The Oxford Dictionary of Late Antiquity. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-866277-8.

- Emrani, Haleh (2009). Like Father, Like Daughter: Late Sasanian Imperial Ideology & the Rise of Bōrān to Power. University of California.

- Ghanoonparvar, Mohammad R. (1989). "Būrānī". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. IV, Fasc. 5. pp. 554–555.

- Gignoux, Ph. (1987). "Āzarmīgduxt". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. III, Fasc. 2. p. 190.

- Howard-Johnston, James (2010). "Ḵosrow II". Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- Kia, Mehrdad (2016). The Persian Empire [2 volumes]: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-61069-391-2.

- Malek, Hodge Mehdi; Curtis, Vesta Sarkhosh (1998). "History and Coinage of the Sasanian Queen Bōrān (AD 629-631)". The Numismatic Chronicle. Royal Numismatic Society. 158: 113–129. JSTOR 42668553. (registration required)

- Martindale, John Robert; Jones, Arnold Hugh Martin; Morris, J., eds. (1992). The Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire, Volume III: A.D. 527–641. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-20160-5.

- Pourshariati, Parvaneh (2008). Decline and Fall of the Sasanian Empire: The Sasanian-Parthian Confederacy and the Arab Conquest of Iran (PDF). London and New York: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84511-645-3.

- Schmitt, Rüdiger (2005a). "Personal Names, Iranian iv. Sasanian Period". Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- Schmitt, Rüdiger (2005b). "Personal Names, Iranian iv. Parthian Period". Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- Shahbazi, A. Shapur (2005). "Sasanian dynasty". Encyclopaedia Iranica.

Further reading

- Kuntz, Roger; Warden, William B. (1983). "A Gold Dinar of the Sasanian Queen Buran". Museum Notes. The American Numismatic Society. 28: 133–5. JSTOR 43573666. (registration required)